Neurologic Evaluation of Low Back Pain

Megan M. Shanks

key points

Most low back pain is from a nonspecific cause and will resolve with or without treatment in a few weeks.

Some less common causes of low back pain should not be missed—these include cauda equina syndrome, neoplasm, infection, and unstable fracture.

Evidence-based reviews of acute back pain increasingly recommend less initial imaging, less invasive treatment, and increased patient physical activity.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

A majority of doctors will encounter low back pain as a patient complaint. It comes second only to upper respiratory infections for sheer numbers of doctor visits and missed workdays. In young and middle-aged adults, it is the leading cause of activity-limiting illness. In Western countries, 50% to 80% of the adult population will have some level of back pain during their lifetime, and 15% to 30% within the past year. About 2% to 5% of low back pain patients will develop chronic low back pain (i.e., lasting more than 4 to 6 weeks), with psychosocial issues found as an even greater factor in these patients. The majority of patients recover within 4 to 6 weeks no matter what treatment they receive, but recurrence is also common. The neurologic approach to low back pain is emphasized here, especially for the 2% to 5% of low back pain patients with sciatica or radicular nerve pain that can radiate past the knee, and other disorders involving the lumbosacral nerves such as lumbosacral spinal stenosis and the cauda equina syndrome.

ANATOMY

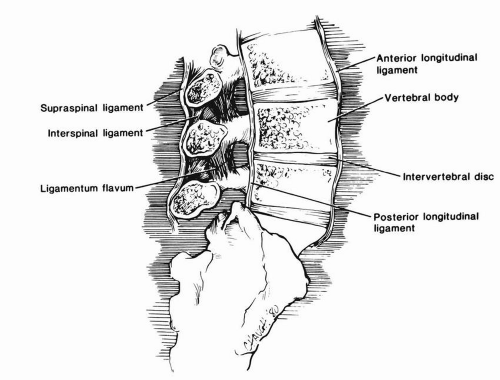

Much about the mechanics of low back pain is not well understood. Other than the spinal cord and radicular nerves, structures that are known to possess nociceptive (pain) fibers include the outer annulus of the disc, the periosteum of the vertebral bodies, the blood vessel walls, the anterior dura, the posterior longitudinal ligament, the fibrous capsule of the facet joint, and the sacroiliac joint. Damage to or around these structures often, but not always,

is a cause of pain. Approximately 85% of low back pain has no clear related injury to these structures and is known as nonspecific back pain. This is sometimes classified as nonspecific degenerative disease, myofascial pain, muscle spasm, or strain. The following details of spine anatomy may be a helpful reference in understanding the known causes and exam findings in more depth.

is a cause of pain. Approximately 85% of low back pain has no clear related injury to these structures and is known as nonspecific back pain. This is sometimes classified as nonspecific degenerative disease, myofascial pain, muscle spasm, or strain. The following details of spine anatomy may be a helpful reference in understanding the known causes and exam findings in more depth.

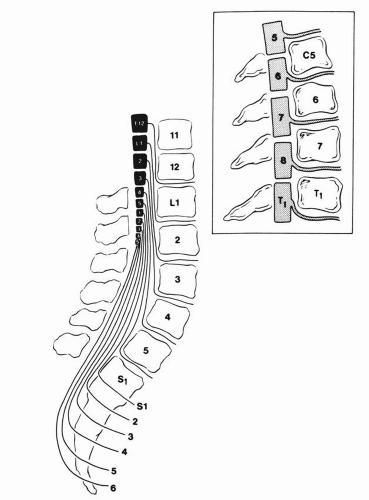

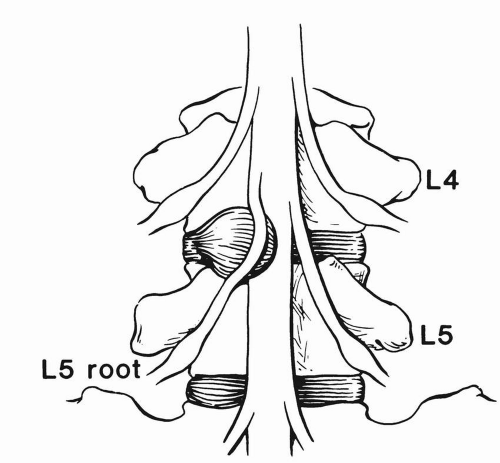

The low back consists of five lumbar vertebral bodies, and a single fused bony sacrum, with the coccyx (tailbone) below. The lumbar vertebrae are stabilized by various ligaments, as well as the surrounding musculature, and cushioned by intervertebral discs (Fig. 19.1). The dorsal vertebral spine makes up the protective neural arch, surrounding the spinal cord canal and descending nerve roots (Fig. 19.2). The adult spinal cord ends as the conus medullaris at L1-2, with the lumbosacral nerve roots descending through the spinal canal as the cauda equina. The descending five lumbar, five sacral, and single coccygeal nerve roots exit through their corresponding lateral neural foramina. Unlike the cervical nerve roots, the lumbar nerves descend for several levels before exiting below the corresponding numbered vertebral body (the L4 root between the L4 and L5 vertebrae, and so on). Thus, a far lateral L4-5 disc herniation will cause an L4 radiculopathy pattern. But more commonly the disc herniates posterolaterally within the neural canal, causing the more medially descending L5 root to be compressed (see Figs. 19.3 to 19.5). The most common disc herniation and root syndromes are the L4-5 (L5 root) and L5-S1 (S1 root). The joint between each lumbar vertebral body is the facet (zagopophyseal) joint. The pars articularis is the supportive bony bridge connecting the superior and inferior articular facets, and is prone to stress fracture (see Spondylosis).

STRUCTURAL CAUSES

Muscle/Ligament Pain

Sprain or strain from minor trauma is the most common cause, although the etiology of pain from “spasm” is not well described. The onset is often related to unaccustomed physical activity or sudden unexpected movement. The pain limits movement and is painful with palpation of the back but without neurologic symptoms; that is, pain does not radiate into the legs, with no associated numbness, no weakness that is not related to pain, and no bowel or bladder symptoms.

Disc Herniation

Minor trauma is often an inciting factor, although it may be spontaneous. Disc bulging or dehydration can promote arthritic and

ligamentous change. Discs may also be a site of infection, or discitis. Disc herniation without nerve impingement can cause a focal back pain without radiation down the legs past the knee, or be asymptomatic. Pain is typically worse with bending, coughing, or sneezing (see Neurogenic Pain, and Neurologic Exam below for symptoms found with specific nerve root impingements).

ligamentous change. Discs may also be a site of infection, or discitis. Disc herniation without nerve impingement can cause a focal back pain without radiation down the legs past the knee, or be asymptomatic. Pain is typically worse with bending, coughing, or sneezing (see Neurogenic Pain, and Neurologic Exam below for symptoms found with specific nerve root impingements).

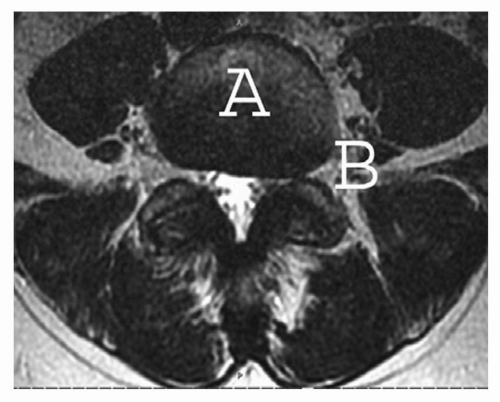

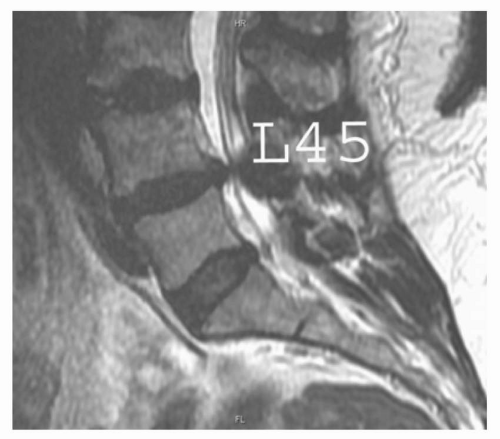

FIGURE 19.4 Sagittal spine MRI showing a posterolateral L4-5 disc herniation causing spinal canal narrowing. |

Neurogenic Pain

This is called “sciatica” or radicular pain. Multiple etiologies can be the source of nerve impingement. Most commonly disc herniation causes nerves compression either in the spinal canal or neural foramen, but narrowing may also be caused by arthritic change, ligamentous hypertrophy, or often by a combination of all three. These areas may also be compromised by tumor, infection, or inflammatory disease. A typical presentation is that of a sharp shooting pain down the leg or legs, often with a tingling numbness, with a particular pattern of weakness if severe.

▪ SPECIAL CLINICAL POINT: It is often stated that radicular pain can be differentiated from other causes of radiating back pain by traveling below the knee; this may not be true for higher lumbar roots L1-3.

Gradual narrowing of the spinal canal in the lumbosacral region can cause spinal stenosis around multiple nerve roots. Degenerative disease of bone, disc, and ligaments is the most common cause. This can cause a specific pattern

of pain referred to as “neurogenic claudication.” Like vascular claudication, exercise can bring on aching or cramping pain in the back, buttocks and legs, and sitting or standing still is needed to relieve the pain. Patients with neurogenic claudication may notice over time that the distance they can walk before they are stopped by pain becomes progressively shorter. Lumbar flexion may ease the pain. Low back pain is typically seen in neurogenic claudication, but may be absent.

of pain referred to as “neurogenic claudication.” Like vascular claudication, exercise can bring on aching or cramping pain in the back, buttocks and legs, and sitting or standing still is needed to relieve the pain. Patients with neurogenic claudication may notice over time that the distance they can walk before they are stopped by pain becomes progressively shorter. Lumbar flexion may ease the pain. Low back pain is typically seen in neurogenic claudication, but may be absent.

Sudden simultaneous compression of multiple lumbosacral nerve roots causes the cauda equina syndrome. It can be caused by disc herniation, tumor, abscess, hemorrhage, spondylolisthesis (vertebral slippage), or fracture.

▪ SPECIAL CLINICAL POINT: Cauda equina syndrome is a neurologic emergency requiring immediate attention to prevent permanent neurologic damage. It should be suspected if the patient complains of sudden back and leg pain with leg weakness, loss of reflexes, saddle numbness,and bladder or bowel dysfunction with loss of anal tone.

Spinal cord or conus medullaris compression have similar symptoms as cauda equina syndrome, but with the addition of upper motor signs such as hyperreflexia and spasticity. This will be found with lesions in the L1-2 region or above, as the cord ends at this level in adults.

Involvement of multiple nerve roots that can be rare causes of severe back pain include Guillain-Barré syndrome (acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy) with progressive weakness and areflexia, arachnoiditis (inflammatory clumping of the nerve roots), and carcinomatous meningitis. Low thoracic or high lumbar cord involvement may also cause low back pain, including transverse myelitis and spinal cord infarct. Cord infarct may spare the dorsal columns that carry joint position and vibration sense, but will affect pain and temperature as well as all strength below the level of infarct. Acute spinal shock from any cause (trauma, cord infarct, transverse myelitis) may cause initial flaccid paralysis and areflexia, but typically also has severe sensory loss.

Bony Spine Pain

Fracture or damage from trauma or osteopenia, neoplasm (metastases, primary bony tumors), infection or arthritis (inflammatory, degenerative, Paget disease) may affect the vertebral bodies, facet joints, pars articularis, or sacroiliac joints. Osteomyelitis of the spine may develop slowly with symptoms of focal, unrelenting back pain not relieved by rest. Fever and chills may also be present. This may lead to compressive neurologic symptoms by forming an epidural abscess. Compression fracture of the vertebral bodies after minor trauma may cause a constant focal tender region of the spine. Repetitive stress to the pars articularis may cause them to fracture, which is referred to as spondylolysis. This can be entirely asymptomatic, or cause focal back pain with flexion or extension. It is notable cause of low back pain in athletes. It predisposes patients to spondylolisthesis, which is the slipping forward of one vertebral body over the next. This may by itself cause unilateral or bilateral back pain, or cause root irritation with radiating leg pain. Spondylosis is arthritic change or bony spurring from the vertebral margins, and does not cause pain unless there is nerve impingement. Facet joint arthritis may cause a focal aching tenderness and pain with movement. Spinal deformities such as scoliosis or kyphosis can increase the risk of back pain. Sacroiliac joint pain may be due to arthritis or pregnancy, and causes an aching or sharp pain over the low back where the sacrum joins the pelvis. It is worse with standing or walking. Back pain may also be referred from the hip joints.

Referred Pain from Abdominal or Pelvic Structures

Psychosocial Factors

The levels of life stressors and emotional distress are key in predicting poor outcomes and chronic low back pain. This includes job dissatisfaction, depression, high levels of psychological distress regarding pain and disability, and medicolegal or compensation disputes. This is probably one of the most important factors in nonspecific back pain, but one that is more difficult to rate or treat.

▪SPECIAL CLINICAL POINT: Most cases of low back pain have a benign course, but there are some less common causes of low back pain that should not be missed. These include cauda equina syndrome, neoplasm, infection, and unstable fracture.

EXAM

As a general medical history can point toward the specific causes of low back pain, so too can the general exam. Fever is not always present in infections in or around the spine, but its presence with focal back pain is notable. Abdominal, pelvic, and hip exam may uncover referred sources of pain.

Percuss the spine for focal tenderness as can be seen in fracture, infection, or neoplasm. Palpate the back muscles for spasm and pain. Inspect the skin for signs of shingles or bruising. Investigate the curve and mobility of the back movements.

Neurologic Exam

▪SPECIAL CLINICAL POINT: L5 radiculopathy is the most common radicular syndrome. The hallmarks are shooting pain into the leg, big toe dorsiflexion weakness, and trouble inverting the foot. The main differential diagnosis is peroneal palsy from a more distal lesion of the peroneal nerve, but this latter syndrome is not associated with shooting pain and the weakness is usually more pronounced (severe foot drop) than seen in L5 radiculopathy.

A distinction can be made between a drop foot from an L5 radiculopathy and that of a common peroneal neuropathy by checking for foot inversion (tibialis posterior). Peroneal palsies should spare foot inversion. Weakness of foot inversion suggests an L5 radiculopathy rather than a peroneal neuropathy.

A neurologic exam of the lower extremities is important in any low back pain patient to rule out nerve compromise, particularly if the clinical history suggests radiating pain or possible weakness or numbness.

Motor Strength (See also Table 19.1) Ask the patient to push against resistance. For L2-4, ask them to lift the leg at the hip and push the knees toward each other. For L5, have them push the knees apart, raise the foot at the ankle (this may also have some L4), flex at the knee (this may also have some S1), and tilt the foot inward and outward. For S1, have them push downward with the foot, or from a supine position have them try to keep the leg on the bed while the leg is raised. A straight leg raise (SLR) test may also be checked at this time with passive lifting of the leg to between 30 and 70 degrees to assess for painful radicular nerve stretch. SLR can also be tested from a sitting position, with gradual straightening of the leg. Patrick sign can be tested to check for referred pain from the hip or sacroiliac joint. Patrick sign is also referred to as FABER for flexion, abduction, and external rotation of the hip. Be aware that pain with certain movements may cause the so-called “give-way weakness” that will resolve when pain is controlled. Be sure to ask the patient whether any pain is occurring if weakness is found. Give-way can also be seen in a non-neurologic or diffuse pattern in embellishment or malingering. Check increased tone by lifting the legs at the knees gently to see if the heel drags along the bed or lifts up in a spastic bouncing fashion. A patient in pain may not be able to relax enough for this test to be done.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree