Chapter 145 Neurologic Monitoring Techniques

Abstract

Nocturnal spells often present diagnostic problems in sleep medicine because the history alone might not provide sufficient information to differentiate among the various diagnostic possibilities. Standard polysomnography (PSG) is helpful in defining the state and stage of sleep from which such nocturnal spells emerge, but it has limitations in diagnosis because behavioral analysis often is not included and the number of channels devoted to electroencephalography (EEG) is limited. These shortcomings are especially pertinent to the evaluation of suspected nocturnal epileptic seizures, which are defined by behavioral and motor manifestations in addition to EEG criteria.1 Both behavioral and EEG analyses are critical for characterizing epileptic seizures and for distinguishing them from parasomnias.

The behavioral and EEG manifestations of nocturnal spells caused by parasomnias, neurologic disorders, and psychiatric disorders can be characterized more precisely by combining standard PSG with video recordings and extensive (12 or more channels) EEG montages.2 This chapter emphasizes the methodology and indications for video-EEG PSG (VPSG) in the diagnosis of nocturnal events. The methodology and roles of routine EEG, short-term continuous video-EEG monitoring (STM), long-term continuous video-EEG monitoring (LTM), and ambulatory monitoring are addressed.

Methodology

Technical Aspects of Electroencephalography

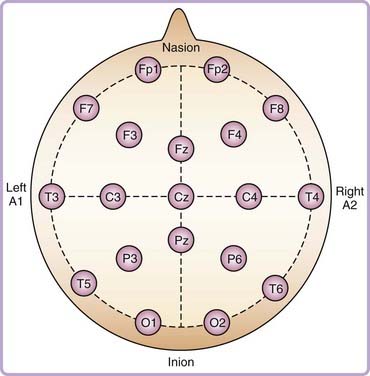

The EEG measures the difference in electrical potential between pairs of electrodes placed on the scalp. These signals, reflecting synchronous postsynaptic potentials in large groups of neurons, are amplified and filtered to produce an analog or digital recording.3 The international 10-20 system of EEG electrode placement is customarily used, in which the 10-20 refers to 10% and 20% of the distances between standard cranial landmarks (Fig. 145-1).4,5 Each electrode site is identified with a letter representing the underlying region of the brain and with a number indicating a specific position above that region, with odd numbers indicating the left hemisphere and even numbers indicating the right hemisphere (e.g., T3 represents a left midtemporal electrode).

The EEG montages used in a combined EEG-PSG study depend on the clinical indication and the number of channels available for recording (Table 145-1). The channels suggested in this text are in addition to those recommended by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) for the scoring of sleep stages.6 Physicians and technicians involved in the use of EEG monitoring techniques require a solid knowledge of the principles of EEG recording and interpretation. Additional information regarding EEG methodology is available in a standard EEG text.7

Table 145-1 Sample Attended Electroencephalographic Montages

| NUMBER OF AVAILABLE CHANNELS | MONTAGE |

|---|---|

| 8 | F7-T3, T3-T5, T5-O1, F8-T4, T4-T6, T6-O2, F3-C3, F4-C4 |

| 10 | Fp1-F7, F7-T3, T3-T5, T5-O1, Fp2-F8, F8-T4, T4-T6, T6-O2, F3-C3, F4-C4 |

| 12 | Fp1-F7, F7-T3, T3-T5, T5-O1, Fp2-F8, F8-T4, T4-T6, T6-O2, F3-C3, C3-P3, F4-C4, C4-P4 |

| 14 | Fp1-F7, F7-T3, T3-T5, T5-O1, Fp2-F8, F8-T4, T4-T6, T6-O2, F3-C3, C3-P3, P3-O1, F4-C4, C4-P4, P4-O2 |

| 16 | Fp1-F7, F7-T3, T3-T5, T5-O1, Fp2-F8, F8-T4, T4-T6, T6-O2, Fp1-F3, F3-C3, C3-P3, P3-O1, Fp2-F4, F4-C4, C4-P4, P4-O2 |

| 18 | Fp1-F7, F7-T3, T3-T5, T5-O1, Fp2-F8, F8-T4, T4-T6, T6-O2, Fp1-F3, F3-C3, C3-P3, P3-O1, Fp2-F4, F4-C4, C4-P4, P4-O2, Fz-Cz, Cz-Pz |

| 24 | Fp1-F7, F7-T3, T3-T5, T5-O1, Fp2-F8, F8-T4, T4-T6, T6-O2, Fp1-F3, F3-C3, C3-P3, P3-O1, Fp2-F4, F4-C4, C4-P4, P4-O2, Fz-Cz, Cz-Pz, T1-T3, T3-C3, C3-Cz, Cz-C4, C4-T4, T4-T2 |

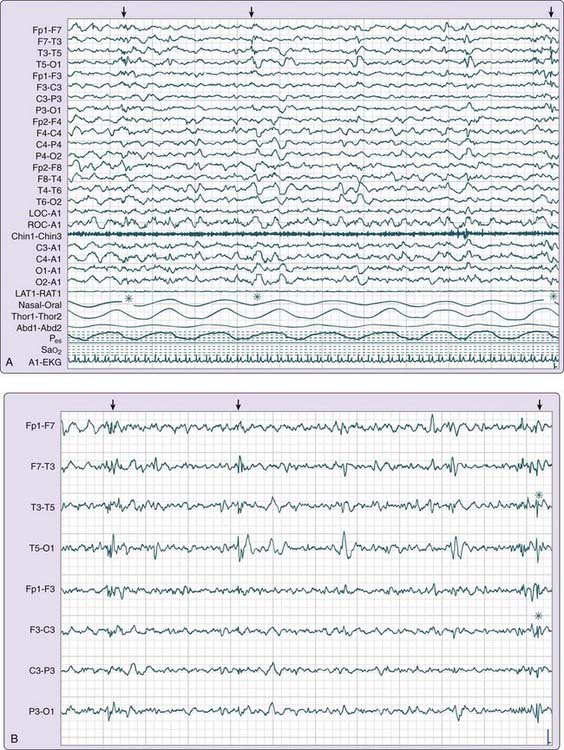

The recording may be viewed at a variety of display settings. Filters, sensitivities, and montages may be adjusted to characterize events of interest and to help distinguish abnormalities from artifacts or normal variants. For example, certain montages can more easily identify and distinguish artifacts from interictal epileptiform discharges (IEDs), defined as epileptic activity occurring between seizures. Digital EEG enhances the detection and review of IEDs by allowing for remontaging, changing the display settings that influence temporal resolution, and isolating specific channels for review (Fig. 145-2). For example, by altering the display settings, synchronous delta or theta activity characteristic of non–rapid eye movement (NREM) arousal disorders may be more easily distinguished from spike-wave activity or an evolving ictal (seizure) pattern characteristic of an epileptic seizure disorder.

Several digital EEG-PSG systems share a common platform with epilepsy monitoring systems, allowing data obtained during a PSG to be analyzed by IED detection programs. Conversely, a study performed in the epilepsy-monitoring unit can be enhanced via the addition of electrooculogram (EOG) and chin electromyogram (EMG) electrodes to score sleep and determine the stage of sleep that precedes a particular event. This can be diagnostic in the case of distinguishing dissociative events, which rarely occur during sleep,8 from epileptic seizures, which can occur during sleep or wakefulness.

Daytime Electroencephalography

Daytime EEG is used to look for IEDs, which support the diagnosis of a seizure disorder in many clinical settings.7 In addition to the electrodes listed earlier, central (Fz, Cz, Pz) and ear (A1, A2) electrodes are included. Nasopharyngeal electrodes, although used in the past, are not recommended because they are uncomfortable, are prone to artifact, and rarely provide additional information. The activating techniques of hyperventilation and intermittent photic stimulation are routinely performed and can bring out focal asymmetries or epileptiform activity.

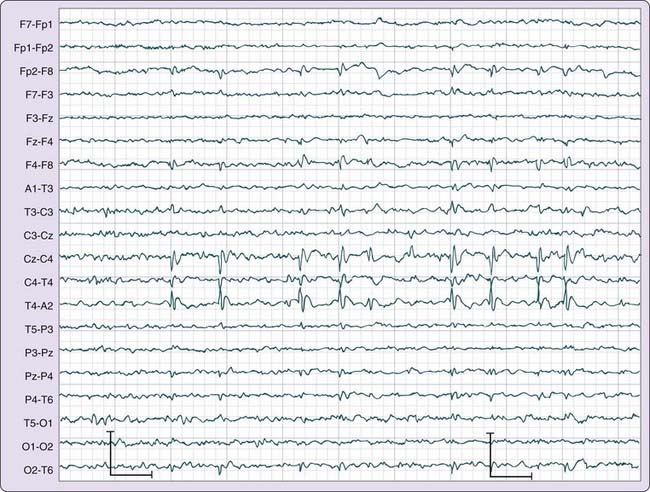

Although seizures are not uniformly recorded during a routine EEG, focal IEDs or generalized spike-and-wave discharges may be observed and can assist in the classification of an epileptic syndrome as partial or generalized. The location of IEDs, which can be determined with the use of an extended EEG montage, can clarify the nature of the epilepsy syndrome and its prognosis.9 For example, benign epilepsy of childhood with centrotemporal spikes has an excellent prognosis (Fig. 145-3). In contrast, some temporal lobe IEDs may be refractory to medical treatment, and the patients can become candidates for epilepsy surgery.

Video-Electroencephalography Polysomnography

When the history does not allow the physician to diagnose nocturnal spells associated with complex movements and behavior, recording of the sleep-related event in question might allow definitive diagnosis. VPSG, which combines video recording with an extended EEG montage and with other standard PSG physiologic monitoring, is useful in characterizing unusual behavior and movements during sleep. Diagnostic considerations for patients with complex actions at night can include epileptic seizures, NREM arousal disorders, REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD), rhythmic movement disorder, or psychiatric disorders such as panic disorder or dissociative disorder. Episodes associated with these disorders have specific clinical features as discussed in Chapters 92 and 94 to 96. Events recorded with VPSG are reviewed to characterize the motor and behavioral manifestations of the event and the EEG-PSG features, including the stage of sleep preceding the event, the time of the event relative to sleep onset, and EEG patterns occurring during the event or between events.

The stage of sleep from which the spells emerge and the time of the spell relative to sleep onset provide useful diagnostic information. For example, the actions accompanying the NREM arousal disorders arise from stage N3 or sometimes stage N2 sleep, usually in the first third of the sleep period (see Chapter 94), whereas those associated with RBD emerge from REM sleep, most commonly in the last third of the sleep period (see Chapter 95). Epileptic seizures are more common during NREM sleep than during REM sleep (see Chapter 92).10 Rhythmic movements associated with rhythmic movement disorder usually occur during sleep–wake transitions, and dissociative episodes emerge from wakefulness. Nocturnal panic attacks occur from NREM sleep, usually at the transition from Stage N2 to N3.11

Specific EEG patterns associated with nocturnal spells are discussed in the section Relative Indications, Advantages, Disadvantages, and Limitations. If complex partial seizures are a diagnostic consideration, the EEG montage should emphasize the use of electrodes placed over the temporal lobes (e.g., F7, T1, T3, T5). If benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes is a consideration, the montage should include the parasagittal region (e.g., C3, C4). The specific montage that is used depends on the number of channels available for EEG. Sample montages for 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 19, and 24 channels are shown in Table 145-1.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree