Parkinson’s disease is a multifaceted disorder with a complex variety of symptoms within both the motor and nonmotor domains. Therefore, management by a multidisciplinary team with specialists from a range of complementary disciplines seems preferable over a single-clinician approach. In this chapter, we focus on the merits of complementary nonpharmacologic interventions in the management of Parkinson’s disease, and discuss various ways to organize multispecialty approaches. We specifically highlight a Dutch model to organize Parkinson’s disease care, and review our own experience both within everyday clinical practice and within formal scientific evaluations. We will also address how to engage patients and their informal caregivers, as we believe that the team will be incomplete without their active involvement.

Although Parkinson’s disease was regarded initially as a motor disease, it is now clear that the well-known motor features are part of a much broader symptom complex(1). The nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease, including sleep problems, depression, cognitive impairment, pain, and gastrointestinal symptoms, are increasingly recognized as a relevant part of Parkinson’s disease (see Chapter 7) (2). In fact, these nonmotor symptoms have an enormous impact on the quality of life, and this impact often exceeds the burden caused by motor features (3–5). These nonmotor features are very common, even in early stages of the disease (6), with on average 8 to 12 different symptoms per patient (3–7). Despite this high prevalence, the nonmotor symptoms mostly remain unrecognized and untreated (5,8).

Traditionally, Parkinson’s disease has been managed by pharmacologic treatment, including levodopa and dopamine antagonists (see Chapter 11) (9). These treatments are indeed effective for most motor symptoms, but their effectiveness does not cover the whole spectrum of symptoms. In fact, some nonmotor symptoms might actually even worsen due to dopaminergic stimulation (8). In addition, long-term use of dopaminergic treatment is limited by motor fluctuations (e.g., response fluctuations and dyskinesias) and difficulties to optimally schedule medication intake as the therapeutic window narrows in time. Surgical procedures (see Chapter 48), that is deep brain stimulation or infusion therapies, can be considered in the advanced stages of the disease, yet, there is little guidance as to which therapy is most appropriate for a particular patient (10). Moreover, not all patients are appropriate candidates for these advanced treatments.

NONPHARMACOLOGIC INTERVENTIONS

Considering the limitations of pharmacologic care to optimally manage all symptoms in Parkinson’s disease, in particular the nonmotor symptoms, complementary nonpharmacologic interventions should be considered when attempting to offer optimal therapeutic efficacy to patients with Parkinson’s disease. During the last decade, several task forces, including those from the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) and the UK-based National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE), independently constructed multidisciplinary guidelines and developed quality indicators for Parkinson’s disease. All documents emphasize the importance of managing the broad symptom complex of Parkinson’s disease, including both motor and nonmotor domains, and recommend that patients should be referred and have access to a wide range of medical and nonmedical specialists (11–14). Indeed, over 20 different health-care professionals can potentially be involved in Parkinson’s disease care to optimally treat the complex set of motor and nonmotor symptoms (13). A list of these health-care professionals and their unique contribution to the treatment is provided in Table 51.1. This long list underscores that, besides pharmacologic and surgical interventions, which are traditionally the cornerstone of Parkinson’s disease management, a range of other treatment modalities can be considered to offer optimal care to patients with Parkinson’s disease and their families.

GENERIC PRINCIPLES OF ALLIED HEALTH CARE

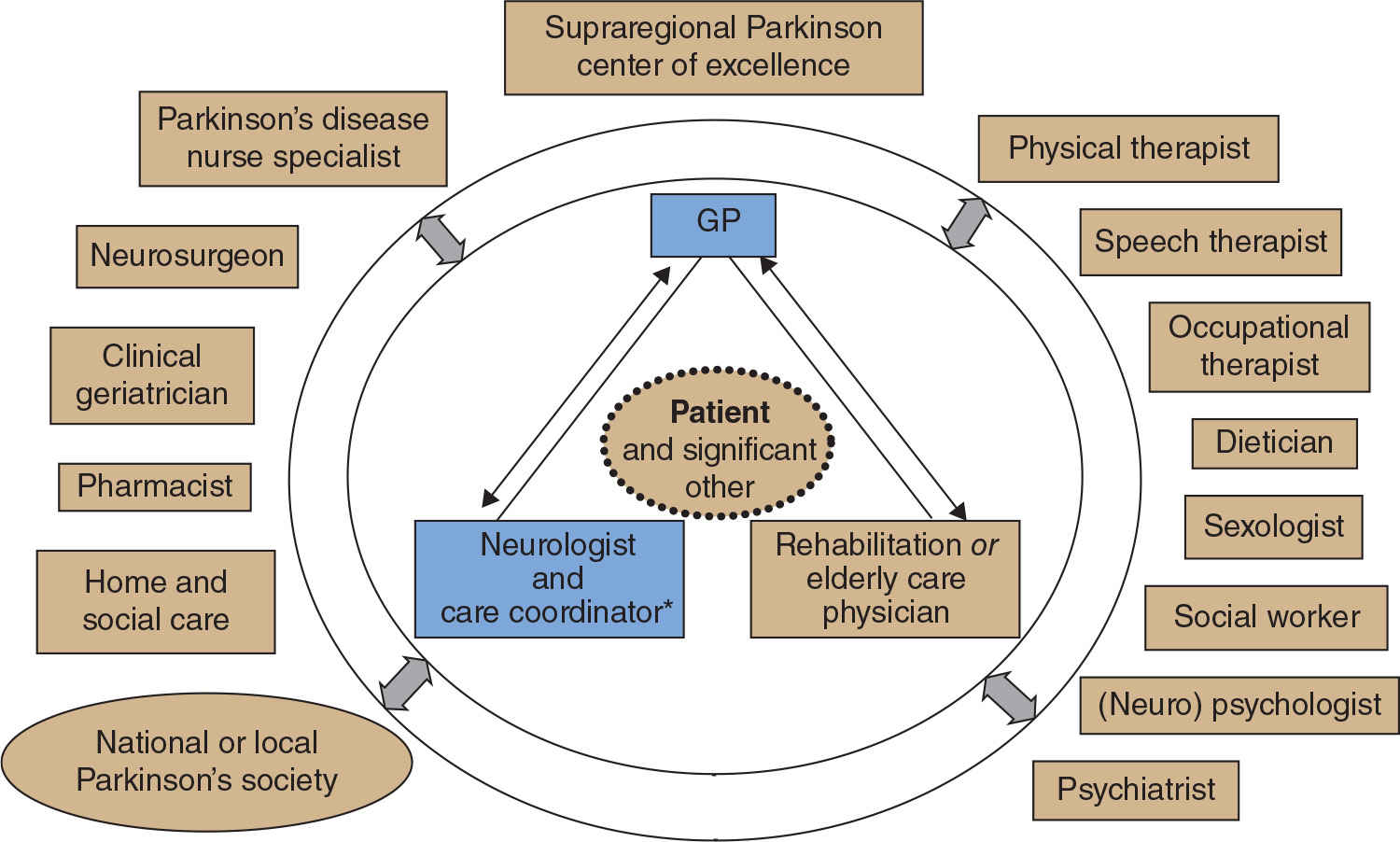

Nonmedical interventions are delivered by allied health professionals, who include physical therapist, occupational therapist, speech–language therapist, and dieticians, and by social workers, psychotherapists, and sexologists (Table 51.1; Fig. 51.1). Allied health therapists aim to improve the patient’s participation in everyday activities by minimizing the impact of the disease and/or by improving motor functioning, for example, gait or speech. The underlying working mechanism of these motor treatments differs from medical treatment. While pharmacotherapy or neurosurgery aims to correct the nigrostriatal dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease, allied health therapists treat motor functions by trying to bypass the basal ganglia via the intact cortical pathways, thereby compensating the typical hypokinetic symptoms (15,16). This is done by instructing and training the patient to consciously enlarge movements, like purposely taking large strides when walking and raising the voice loudness when talking. Other specific motor strategies in the treatment of patients with hypokinetic-rigid features are (a) the use of visual, acoustic, or tactile cues to initiate and maintain movements during activities, for example, by using a metronome to improve walking speed (17,18), (b) to divide complex movements into sequences of simple subcomponents that can be trained by exercise, for example turning in bed (16,17,19), and (c) to avoid multitasking by instructing the patient to focus on the primary task at hand and, when complete, to consciously switch to another task (16,20), for example, to first finish drinking coffee safely, then to focus on making a conversation (21).

| Overview of Disciplines (in Alphabetical Order) That May Be Involved in Parkinson’s Disease Care. The Large Number of Professional Reflects the Complexity of This Condition |

Discipline | Primary Interest |

Dietician | • (Risk for) Weight loss and malnutrition • Dietary advices related to medication or surgical procedures • Dysphagia • Constipation |

General practitioner | • Recognition of symptoms and side effects of treatment, with subsequent referral to neurologist |

Geriatrician | • Elderly patients with complex set of comorbidities that need to be addressed, e.g., internal medicine, psychiatry, falls, or polypharmacy |

Neurologist | • Diagnosis, inventory of spectrum of symptoms, and disease process • Medical treatment, expert review of PD, and management of complications • Referral to other health professionals |

Neuropsychologist | • Changes in cognition, memory, and behavior |

Neurosurgeon | • Surgical procedures |

Occupational therapist | • Cognitive impairments related to functional tasks • Disabilities in activities of daily living, and safety and independence to perform these activities • Support for family and caregivers to help patients perform activities of daily living |

Ophthalmologist | • Visual problems • Oculomotor disorders, including vertical gaze palsy and diplopia |

Parkinson’s nurse specialist | • Provide guidance, support, and advice • Education to patient and caregiver • Observe symptoms and side effects of medication • Notify increased demands for care, with specific attention to cognitive, psychosocial, sexual, and mood problems • Close communication with neurologist, general practitioner, and other health-care professionals |

Pharmacists | • Check for medication interaction • Enhance therapy adherence |

Physical therapist | • Physical activity, general fitness, muscle strength • Safety and functional independence, safe use of assistive devices • Fear of falling, fear to move • Restrictions in performing transfers (e.g., standing up from a chair, rolling over in bed) and walking (like freezing) • Disorders of balance and postural control • Prevent falling • Motor learning and strategy training (e.g., breaking down activities) |

Psychiatrist | • Apathy, loss of taking initiative • Behavioral problems • Delirium • Depression • Anxiety, panic attacks |

Psychologist | • Stress of patient or caregiver • Complex psychosocial problems • Coping • Problems with relationship • Mood and anxiety disorders |

Rehabilitation specialist | • Observation and treatment of problems with activities of daily living, household activities, or participation • Provide assistive devices • Advice on job participation |

Sexologist | • Problems with sexual functioning |

Sleep medical specialist | • Diagnosis of complex sleep disorders. Treatment of sleep disorders, such as insomnia, vivid dreaming, and excessive daytime somnolence |

Specialized elderly care physician | • Daycare, short-stay or long-stay, regarding complex motor and nonmotor pathology • Palliative care • Residential care |

Speech–language therapist | • Problems with speech and verbal communication • Swallowing disorders • Drooling of saliva |

Social worker | • Psychosocial problems, e.g., coping or problems with daytime activities • Caregiver burden (psychological and financial) • Facilitate acquisition of services and inquiries, including legislation and regulation |

Urologist | • Urinary problems, e.g., incontinence and urgency, to exclude other causes besides PD • Erection and ejaculation dysfunction |

Complementary and alternative therapies | • These therapies (e.g., nutritional supplements, massage therapy, acupuncture, homeopathy) are used commonly by PD patients |

Source: Adapted from Bloem BR, et al. Multidisciplinaire richtlijn Ziekte van Parkinson [Multidisciplinary guideline Parkinson’s disease] Alphen aan den Rijn: Van Zuiden Communications B.V., 2010. | |

Figure 51.1. Model for optimal organization of team-oriented care for Parkinson’s disease. Patients and their (informal) caregivers have a central role in this model and are in close contact with a core team of specialists, including the neurologist and Parkinson’s disease nurse, general practitioner, and elderly care specialist and rehabilitation specialist. On a tailored basis, other disciplines might be involved within the treatment team. (From Bloem BR, et al. Multidisciplinaire richtlijn Ziekte van Parkinson [Multidisciplinary guideline Parkinson’s disease]. Alphen aan den Rijn: Van Zuiden Communications B.V., 2010.)

Obviously, when the disease progresses and cognitive functioning declines, support by the caregiver to assist the patient in using cues or applying movement strategies becomes unavoidable. Another typical aspect of allied health treatment is that the training and support of mobility and daily activities takes place at home (22–24). Many limitations are manifested in the patient’s own home environment, for example, freezing of gait can only be properly compensated and monitored at home. Again, the caregiver’s assistance may be needed in making home adjustments, as some patients are reluctant to implement adaptations. Finally, the detailed observations by allied health professionals can sometimes assist the neurologist in making the correct neurologic diagnosis, for example, by observing specific “red flags” during the baseline assessment or treatment sessions; an example is the observation of apraxia by the occupational therapist while observing the patient in the kitchen, or the observation of a cerebellar component to speech by the speech–language therapist (25).

PHYSICAL THERAPY

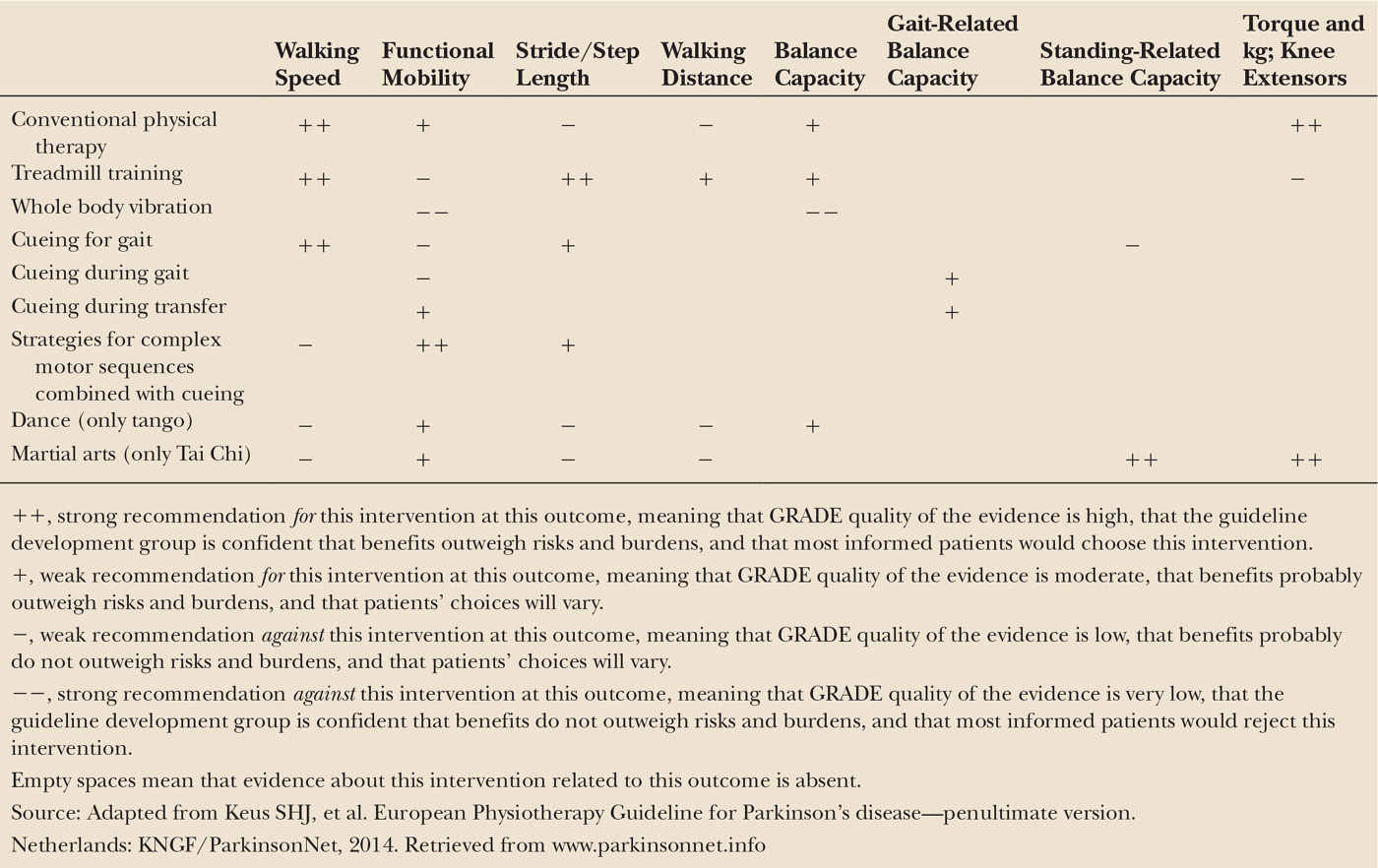

The core areas of physical therapy for patients with Parkinson’s disease are physical capacity and inactivity, transfers, manual activities, balance and falls, gait and additional areas like pain, and respiratory problems. Since 2004, an evidence-based practice guideline for physical therapist working with Parkinson’s patients is available in Dutch and English from the Royal Dutch Society for Physical Therapy (KNGF) (22); this guideline is supported by the Association of Physical therapists in Parkinson’s Disease Europe (APPDE). An update of the evidence was published in 2008, discussing new findings (26). Clear evidence from a meta-analysis and additional treadmill studies underline that exercise therapy can improve physical capacity and gait (27–29) and also the impact of dancing on balance and mobility became apparent. In 2010, an international update of the guideline was initiated by the KNGF in collaboration with 20 European physical therapy associations from 19 associations in 19 countries. This resulted in the first European Physical Therapy Guideline for Parkinson’s Disease in 2014 (30). This fully updated international guideline contains treatment principles, assessment techniques, and interventions that are agreed upon by all participating associations. Considering evidence for treatment, the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE; www.gradeworkinggroup.org) approach was used to construct the graded treatment recommendations for the core areas of physical therapy. These are divided into strong and weak recommendations for or against a treatment, providing physical therapists with a clear decision tool (Table 51.2). In brief, to improve walking speed, conventional physical therapy, treadmill training, and cueing are strongly recommended. To improve functional mobility, strategies for complex motor sequences combined with cueing are strongly recommended. Treadmill training is also recommended to improve stride length, walking distance, and balance. New interventions in this guideline are whole body vibration, dance, and martial arts. Tango dancing and Tai Chi are recommended to improve functional mobility and balance, but whole body vibration is strongly recommended not to use for any of these goals. In addition, Tai Chi is also strongly recommended to improve standing-related balance capacity and muscle strength.

OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY

In 2008, a guideline for occupational practice was published in Dutch and English (23) with recommendations for clinical practice. Occupational therapy is closely related to physical therapy, but the treatment goals are different. Physical therapists focus on improvement of daily functioning by training and compensating basic skills like gait, balance, and transfers, while occupational therapists focus on supporting patients to engage in meaningful activities and roles, which are included in the three domains of self-care, productivity, and leisure activities. The interventions focus on personal skills, on whether the activity itself can be changed and on adaptations in the environment.

This initial guideline was based on evidence from the physical therapy literature (the motor strategies mentioned earlier), supplemented with evidence and best practices for occupational therapy from other neurodegenerative diseases like dementia. Evidence for the benefit of occupational therapy for Parkinson’s disease patients was lacking because most studies were too small (31). This changed in 2014, when the OTiP (Occupational Therapy in Parkinson’s disease) trial was published, showing for the first time that Parkinson’s patients benefit from occupational therapy (32–34). Ten weeks of home-based occupational treatment (n = 124) according to the guideline was compared with no treatment (n = 67) in a multicenter randomized controlled trial (RCT) design with minimization based on disease severity, age, and perceived performance in daily activities at baseline. The OTiP intervention was a mix of strategies “individually tailored to alleviate the problems in activities prioritized by the patient and to suite the patient’s coping style, the patient’s capacity to change, and the environmental and social context in which the targeted activity is usually done.” Significant benefits were found on the primary outcomes, namely both self-perceived performance on meaningful daily activities and satisfaction with performances prioritized activities, measured with the COPM (Canadian Occupational Performance Measure) at 3 and 6 months, but not on the secondary outcomes. Caregivers had better quality of life only at 3 months, but reduction of caregiver burden remained statistically insignificant. An important element of this study is the fact that 124 of 191 patients had Hoehn and Yahr stage 1 of 2, which is milder than the usual disease stage of Parkinson’s disease patients that are referred to allied health professionals. This underlines that patients even early in the disease can have limitations in daily activities that can be improved by dedicated but short interventions.

SPEECH AND LANGUAGE THERAPY

Speech–language therapy for patients with Parkinson’s disease focuses on three domains: speech (hypokinetic dysarthria) and communication (reduced ability to make conversation), swallowing (dysphagia), and—related to dysphagia—involuntary saliva loss (drooling). In 2008, the first evidence-based guideline in this field was published in Dutch and English (24).

Dysarthria reduces intelligibility and interferes with the ability to communicate with others. This is further aggravated by the loss of facial expression (hypomimia) and by cognitive decline, causing word-finding difficulties when the disease progresses. Although large trials with functional outcomes are still lacking (35), there is growing evidence that treatment of hypokinetic dysarthria in Parkinson’s disease patients can be successful. The main approach was already developed and applied in 1995 and complies with the general motor principles described in the earlier paragraphs. The Lee Silverman Voice Treatment (LSVT) is a short but intensive therapy (four times a week, during 4 weeks) to overcome the hypokinetic voice production, small articulation movements, monotony, and even hypomimia by learning to speak louder (36–38). Because breathing, voicing, articulation, and prosody are interconnected, speaking louder automatically improves the other components when these performances are hypokinetic, but intensive treatment is needed because patients with Parkinson’s disease tend to overestimate the volume of their voice (39

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree