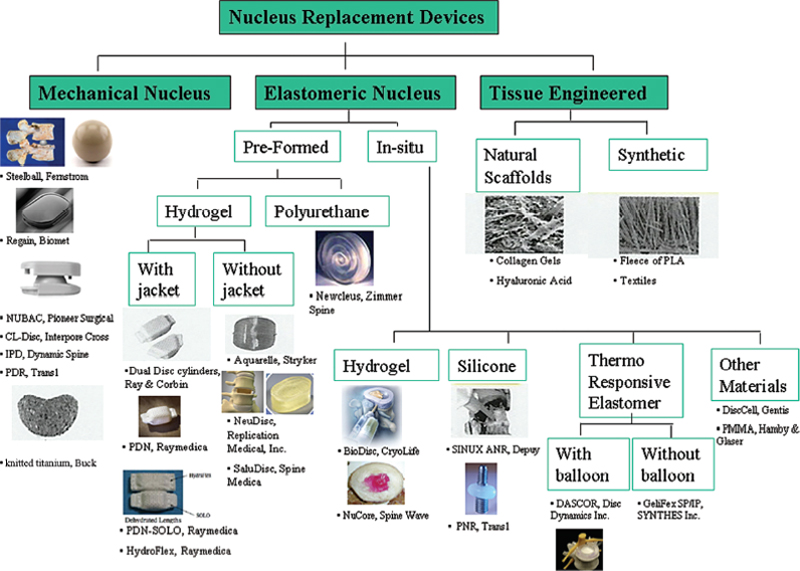

22 Nucleus Augmentation Thomas J. Raley, Qi-Bin Bao and Hansen A. Yuan Low back pain (LBP) is a common condition that affects the majority of the population1,2 and economically impacts our society.3,4 In fact, LBP is second only to the common cold for lost time at work.5 The probability of returning to work decreases dramatically with increased time off work (roughly 50% at 6 months).6,7 The true cause of LBP is unknown, but most likely it is associated with the degeneration of the intervertebral disc (IVD) and age-related deterioration.8,9 With aging, the incidence of LBP, stiffness, and IVD changes increases,10 preceding other degenerative changes in the spine.11–13 The normal mechanical function of the IVD can be summarized as follows: After failure of all conservative treatment, the patient is eligible for surgical intervention. However, the appropriate surgical procedure must address the proposed pain generator. Many treatment options have resulted in poor long-term outcomes. This has led to newer alternative technologies, including NP replacement, IVD replacement, and interbody fusion techniques. In this chapter we will focus on nucleus replacement. Nucleus replacement is a novel approach to replace the degenerated NP and stop the degenerative cascade. Nucleus replacement is meant to mimic the normal function of the functional spinal unit by preserving motion and preventing adjacent segment degeneration. Nucleus replacements may be useful for the treatment of patients with early symptomatic disc disruption. In the future, they may be performed at the time of discectomy to maintain normal biomechanics of the spine and prevent future degeneration. The idea of nucleus replacements originates in the 1950s. Initial attempts at maintaining disc space height and motion involved injection of polymethyl-methacrylate15 or silicone16 into the disc space after nucleotomy. Poor clinical results led to the abandonment of these procedures in favor of inserting preformed devices. Historically, the first human implanted nucleus prosthesis was the Fernstrom ball in 1966. This device was a spherical endoprosthesis made of stainless steel.17 It was meant as a spacer that allowed movement between the adjacent vertebral bodies. It did not restore normal load distribution and was abandoned because of concerns of implant migration and subsidence. However, encouraging long-term results led to further efforts in designing other nucleus replacements.18 Failures with metal ball bearings led to Urbaniak’s study on nucleus replacement with a silicone-Dacron composite device in chimpanzees.19 This work spawned the idea for a preformed or contained implant. In 1981, Edeland20 suggested the implantation of a device that behaved biologically and biomechanically similar to the NP. The device behaved in a viscoelastic fashion and the properties changed to adapt to the loads applied. In 1988, Ray and Corbin21 developed a device based on Edeland’s principles. It consisted of an outer woven polyethylene capsule, with thixotropic gel injected into the collapsed bags after implantation. This device exhibited swelling pressures similar to the natural NP. In 1991 and 1993, Bao and Higham patented hydrogel for nucleus replacement.21,22 The Aquarelle hydrogel nucleus is composed of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), which has a water content of 70% under physiologic loading conditions, much like the natural nucleus. Three of 25 implants extruded through the annulotomy and one through a preexisting tear.23 In the mid-1990s, Ray modified his device to a hydrogel core encased with a polyethylene jacket. This prosthetic disc nucleus was implanted in pairs. The device was implanted in a dehydrated state to facilitate insertion. Biologically, the NP functions as a fluid pump, facilitating body fluid diffusion, which carries the nutrients and removes the metabolites from the avascular disc. Biomechanically, the nucleus inflates the anulus and shares a significant portion of compressive load with the anulus. Therefore, the main objective of nucleus replacement implants is to reestablish normal disc function by restoring disc turgor, tension in the AF, and the disc’s ability to uniformly transfer loads across the disc space. In addition to biocompatibility and fatigue strength, several features should be taken into consideration with the design of the nucleus replacement. First, the nucleus replacement should restore the normal and uniform load distribution to avoid excessive endplate wear. Second, the prosthesis should have sufficient stability in the disc space to avoid implant migration. Third, it should restore the normal body fluid pumping function to enhance nutrient diffusion for the remaining nucleus and inner anulus. Lastly, the implant should be able to be easily implanted.24 The nucleus replacement implants must be biocompatible and be able to endure a considerable amount of loading before failure. Assuming the average individual takes ~2 million strides per year, the average implant would be expected to take the loads of 100 million cycles over 40 years.25 In addition to biocompatibility and withstanding load, the device must also (1) exhibit low wear characteristics with minimal wear debris; (2) allow uniform stress distribution under various physiological loading conditions to avoid subsidence and extrusion of the device; (3) fill the disc space to prevent excessive movement that may lead to extrusion; and (4) enable minimally invasive surgical implantation limiting destruction of the tissues and enhancing the stability of the implant.24 Conceptually and ideally, the nucleus replacement should have the same mechanical properties, such as stiffness and viscoelastic property, as the natural nucleus. The key is to assure a good uniform stress distribution. Choosing the appropriate material is paramount in preventing potential failures. Higher modulus of elasticity devices used in the past are believed to be too stiff for nucleus devices. Most current nucleus prosthesis designs use various elastomers or designs having viscoelastic properties. At this time, nucleus replacements are categorized into two groups: intradiscal implants and in situ curable polymers. The intradiscal devices are biomechanically more similar to the native nucleus and the in situ curable polymers harden after implantation and allow for a less-invasive approach for implantation. The first attempt of in situ formed nucleus prostheses was by Nachemson in 1960.26,27 The main advantage is that it can be injected through a small annular window to reduce the risk of extrusion. It also has the advantage of better implant conformity leading to better stress distribution and implant stability. However, there are several challenges including fatigue of the material, biocompatibility, and leakage of the injectate through the annular incision or another annular defect. Preformed nucleus implants have more consistent polymer properties and biocompatibility. The disadvantages include mismatch with size and shape of the cavity and the need for a larger annular incision for implantation and therefore a risk of device extrusion.28 Another preformed design concept is a device whose shape can be reduced or altered during implantation and restored after implantation. This may be achieved by inflating a balloon with incompressible fluid or by implanting dehydrated hydrogel that rehydrates in the disc. Current materials used for nucleus augmentation include elastomeric materials, including both hydrogels and nonhydrogels, mechanical devices, and tissue-engineered implants. For the nucleus replacement devices made of elastomeric materials, they can be further divided into preformed and in situ formed. Hydrogel materials closely mimic the functions of a normal disc. It has been demonstrated that PVA (nonionic hydrogel) has a similar swelling pressure characteristic as the natural nucleus; three-dimensional expandable polymers with variable water content and biomechanical properties suitable for nucleus replacement. These polymers increase in size and fill the disc space by absorbing water. Their high water content potentially mimics the hydrostatic load bearing and load distribution properties of an intact nucleus. One of the most important characteristics is the ability to absorb and release water depending on the applied load, much like the native nucleus.29 Examples include: These products are injected in a liquid state and solidify within the disc space. Current substrates used include serum albumin polymers, silk-protein polymers, silicone, and polyurethanes. The perceived advantage is that the injection can be done through a minimally invasive approach that will reduce the risk of migration after curing. Examples include The favorable clinical outcomes in both short-term follow-ups of Fernstrom’s device recently prompted several companies to revisit the mechanical nucleus replacement. These new developments have been focused on using less stiff materials and having designs to allow better stress distribution to minimize subsidence. Some of the materials used include polyetheretherketone (PEEK), metal alloys, pyrolytic carbon, and Zirconia ceramics. Examples include It has been shown that reinserting NP cells may preserve the disc by slowing down the degenerative process.33 The seeded cells could be mesenchymal progenitor cells or IVD cells. This matrix would serve as a scaffold to produce adequate mechanical properties, but would not be able to restore disc height. These tissue-engineered scaffolds would be natural or synthetic. Such approaches are currently under study. See Fig. 22.1 for a summary of all nucleus implants. The relationship between degenerative disc disease (DDD) and LBP is very controversial. There has been a poor correlation between DDD on imaging studies and symptoms reported by the general population. A high percentage of asymptomatic individuals have abnormal imaging studies.34,35 Because of this, the decision of surgical intervention is patient dependent and requires a meticulous presurgical workup that includes a thorough history relating to spinal complaints, a thorough physical examination looking for any abnormalities, and a diagnosis that correlates with the imaging studies.

Normal Intervertebral Disc Function

Nucleus Replacement for Intervertebral Disc Degeneration

History

Biomechanics of Nucleus Replacement Implants

Materials and Types of Nucleus Replacement Implants

Preformed Elastomeric Devices

In situ Formed Elastomeric Devices

Mechanical Nucleus Replacements

Nucleus Regeneration

Diagnosis and Surgical Indications

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree