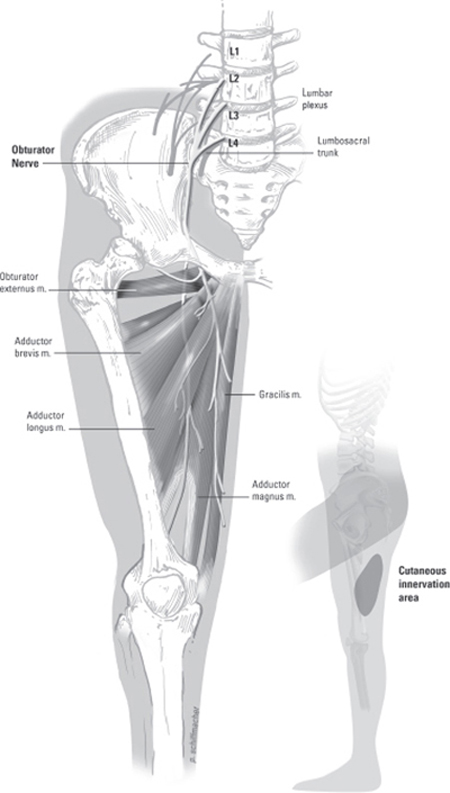

37 Obturator Nerve Injury and Repair A 65-year-old female underwent total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (TAH/BSO) for endometrial cancer. During the procedure, the left obturator nerve was inadvertently sectioned with a sharp dissector. Neurosurgery was consulted intraoperatively for left obturator nerve repair. Using the Pfannenstiel infraperitoneal approach already performed for TAH/BSO, the two ends of the sectioned left obturator nerve were identified where the nerve pierces the medial border of the psoas muscle in the retroperitoneum. Under loupe magnification, the divided ends of the obturator nerve were well exposed and inspected. Both ends of the nerve were found to be cleanly sectioned and easily brought together under minimal tension. The nerve was repaired with two epineurial 6–0 interrupted sutures to avoid excess foreign material. Careful attention was paid to the proper alignment of the nerve sheath and position of fascicles, using superficial vascular markings to guide placement. Further inspection of the nerve identified a distal hemisection several centimeters from the site of primary injury. This area was also repaired with epineurial 6–0 interrupted sutures to achieve coaptation under minimal tension. Both regions of repair were covered with a layer of Tisseel (Baxter International Inc., Deerfield, IL). Abdominal closure was performed by the gynecological service. Immediately postoperatively, the patient complained of pain, numbness, and tingling extending down the medial thigh into the knee, exacerbated by extension and abduction, and moderate weakness (3-/5 motor strength) in left thigh adduction. These classic signs of obturator nerve injury, commonly referred to as the Howship-Romberg sign, gradually improved with vigorous rehabilitation. At 1 year postop, the patient demonstrated 4/5 strength in left thigh adduction with minimal paresthesias along the medial thigh. Obturator nerve injury The obturator nerve originates from L2–4 and is the only motor nerve of the lumbar plexus to pass through the pelvis without innervating any pelvic structures. The major contribution to the obturator nerve is from L3 and the least contribution is usually from L2. After arising from the plexus, the obturator rami fuse and pierce the medial border of the psoas muscle to enter the obturator fossa along the lateral wall of the retroperitoneum. The obturator nerve is accompanied by the obturator artery and vein as it crosses the pelvic cavity through the obturator foramen. In the upper thigh, the nerve divides into an anterior branch and a posterior branch (Fig. 37–1). The anterior branch supplies innervation to the gracilis, adductor longus, and brevis muscles, occasionally to the pectineus, as well as giving rise to an articular branch to the hip joint and a small branch to the femoral artery. The posterior branch innervates the obturator externus, the adductor portion of the adductor magnus, and the adductor brevis muscle when not supplied by the anterior branch. The posterior branch of the obturator nerve also supplies an articular branch to the knee joint. The muscles innervated by the obturator nerve act primarily as thigh adductors but also as flexors, extensors, and rotators of the leg. The most powerful thigh adductor, the adductor magnus, also has a hamstring portion that is innervated by the sciatic nerve. The obturator nerve terminates at the distal aspect of the adductor longus by forming a subsartorial plexus with anterior cutaneous branches of the femoral and saphenous nerves. This plexus along with sensory fibers from the anterior branch of the nerve provides sensation to the medial thigh (Fig. 37–1). The clinical presentation of obturator nerve injury is unpredictable due to both the anatomical variations already described and the presence of an accessory obturator nerve found in 13 to 40% of patients. When present, the accessory nerve communicates with the anterior division of the obturator nerve to supply the pectineus and hip joint. The accessory obturator nerve is often not well delineated and its contribution to thigh adduction is inconsistent. Management options for obturator nerve repair require an understanding of the microanatomy of peripheral nerves. All peripheral nerves consist of nerve fibers grouped into fascicles, divided by septae, which originate from the surrounding epineurial connective tissue. Each fascicle is also surrounded by connective tissue, the perineurium, which is loose enough to allow for exchange of individual nerve fibers between fascicles during the course of the nerve. Within each fascicle, loose connective tissue, the endoneurium, supports nerve fibers. Blood and lymphatic vessels are located between epineurial and perineurial layers. Figure 37–1 The obturator nerve supplies the pectineus, adductor (longus, brevis, and magnus), gracilis, and external obturator muscles. It also supplies a cutaneous sensory zone on the inner thigh (insert). Similar to other injuries of the lumbar plexus (see Chapter 54), obturator nerve injury is infrequent and most commonly iatrogenic but may be due to intrinsic and extrinsic tumors, trauma and pelvic fracture, hematoma, birth trauma, or entrapment in fibrous or muscular bands. The clinical presentation of obturator nerve injury is often a mix of sensory and motor findings. Patients may complain of pain extending down the medial thigh into the knee, and less frequently into the hip. The classic sign of obturator nerve injury, the Howship-Romberg sign, is medial thigh pain relieved by thigh flexion and exacerbated by extension or internal hip rotation. The motor deficits associated with obturator nerve injury are commonly observed as a gait disturbance due to profound weakness in the thigh adductors. The extent of weakness is also variable because of factors such as shared innervation of the adductor magnus between the obturator and sciatic nerves. The clinical presentation is also related to the mechanism of obturator nerve injury. Neurapraxia is a local conduction block, often after traction or compression injury, and may occur during prolonged surgery with the patient’ s leg positioned in acute hip flexion. In this instance, sensory findings predominate rather than adductor weakness, and full recovery usually occurs within 6 weeks. Several cases of obturator nerve neurapraxia have been described in athletes and attributed to entrapment of the anterior branch. Patients describe an aching pain related to exercise that originates at the pubic bone and radiates down the medial thigh. More severe nerve injury is axonotmesis in which axons distal to the site exhibit Wallerian degeneration, leaving the supporting epineurium, perineurium, and endoneurium intact. Although the clinical presentation may involve complete motor, sensory, and autonomic paralysis with muscle atrophy, these patients can make a functional recovery in as little as 6 months without surgical intervention. In the case described earlier, the complete division of the obturator nerve, or neurotmesis, requires surgical repair because both the neural elements and the supporting layers are completely disrupted. Chronic severe obturator nerve injury may present with wasting of the adductor muscles and an externally rotated foot. Because of its anatomical location, isolated obturator nerve injury is rare. Therefore, the differential diagnosis of obturator nerve injury includes many disease conditions that may be found in conjunction with obturator nerve injury. A clinician must consider diagnoses such as inguinal hernias; inguinal ligament enthesopathy; entrapment or injury of the genitofemoral, ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric, or femoral nerve; stress fracture of the pelvis or pubis osteitis; and adductor muscle strain. Because the obturator nerve is most commonly injured during pelvic surgery, any medial thigh pain, paresthesias, or gait disturbance post-operatively warrants a high degree of suspicion for obturator nerve damage. Unlike other peripheral neuropathies, there is no nerve conduction velocity study available for the assessment of the obturator nerve. When injury is suspected, diagnosis relies upon electromyography (EMG) of the thigh adductor muscles. Within 3 to 4 weeks of obturator nerve injury, characteristic EMG findings of muscle membrane instability, such as positive sharp waves and fibrillation potentials, may be detected. A completely bisected nerve will demonstrate loss of all active motor unit potentials. The quadriceps and paraspinal muscles should also be examined for membrane instability and found normal before a definitive diagnosis of obturator nerve injury. An obturator nerve block may yield helpful localizing information regarding a patient’ s source of symptoms but is usually not necessary for diagnosis of obturator nerve injury. Other diagnostic tests vary with the suspected mechanism of injury. In trauma cases, routine computed tomographic (CT) scan or pelvic x-ray may demonstrate fracture or hematoma in the area of the obturator nerve, raising suspicion for the diagnosis. Intrinsic or extrinsic tumors of the obturator nerve are best reviewed with magnetic resonance imaging. The management of obturator nerve injury may be conservative if the injury to the nerve is suspected to be minimal and sensory findings predominate rather than adductor weakness. In this instance, patients may find stretching, massage, or electrical stimulation of the hip flexor and thigh adductor muscles helpful to alleviate paresthesias. With chronic obturator neuropathy, commonly prescribed medications for neuropathic pain such as gabapentin or tricyclic antidepressants may also provide some relief from symptoms, although long-term success is often limited. In most cases of suspected obturator nerve injury, surgical intervention provides the greatest chance for functional recovery. There are several possible routes to gain access to the obturator nerve and lumbosacral plexus, including pelvic brim– extraperitoneal, transperitoneal, lateral-extracavitary, and anterolateral-extraperitoneal approaches to the spine, and the approach used in the case presented earlier, Pfannenstiel infraperitoneal. The pelvic brim–extraperitoneal and Pfannenstiel infraperitoneal approaches both provide access to the obturator nerve, although the transperitoneal approach may be preferable if a wide exposure is required for repair. The microsurgical management of a peripheral nerve injury depends upon both the type of injury and the composition of the nerve. If the damaged nerve contains a complex arrangement of motor and sensory fascicles, individualized fascicular or perineurial repair may be necessary. However, in the case of the obturator nerve, most of the fascicles contain motor fibers, and epineurial repair under minimal tension provides optimal outcome. During epineurial repair, careful attention must still be paid to the alignment of the sheath to avoid twisting of the fascicles. As was done in the case described here, superficial vascular markings on the nerve sheath can help guide the alignment during microsurgical repair. Coaptation of the two nerve ends should be achieved using a minimal number of interrupted nylon sutures, size 6–0 to 10–0, to limit the amount of intraneural scarring, which may obstruct axonal regrowth. To ensure the greatest chance of functional recovery, frayed or devitalized nerve ends must be cleanly trimmed. Because the obturator nerve is fixed at its pelvic entry and exit, excess trimming may lead to a gap and inability to achieve primary closure. In this instance, nerve-grafting techniques may be employed to bridge the gap between the two nerve ends, commonly utilizing the sural nerve as a graft. The decision to surgically repair an obturator nerve, particularly after iatrogenic injury, must not be delayed because the functional outcome is significantly improved with rapid repair. In the immediate postoperative period, the patient should avoid vigorous hip flexion to limit the tension placed on the epineurial sutures. Physical therapy should focus on adductor muscle strengthening. Routine follow-up after obturator nerve repair should include surveillance for neuroma formation, which can lead to pain and sensory symptoms in the obturator nerve distribution. The prognosis and outcome for obturator nerve injury depend on the extent of injury and several associated factors. As emphasized earlier, rapid surgical intervention in cases where it is warranted will optimize functional recovery of the obturator nerve. An unfavorable prognosis is seen in instances of chronic nerve injury with severe muscle atrophy and extensive neural tissue loss. Associated injuries such as pelvic fractures and soft tissue injury in the pelvis will worsen the chances of nerve regeneration due to scarring or interruption of the neural path. In addition, advanced age, delayed repair, and the use of nerve grafts are associated with a poorer prognosis.

Case Presentation

Case Presentation

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Anatomy

Anatomy

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Diagnostic Tests

Diagnostic Tests

Management Options

Management Options

Surgical Treatment

Surgical Treatment

Outcome and Prognosis

Outcome and Prognosis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree