VISUAL TRACT

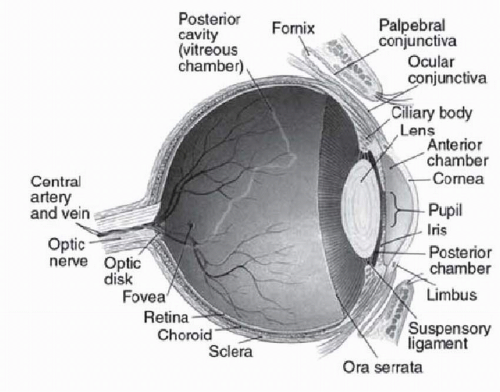

The visual sensory system begins with the cornea and lens focusing light onto the retina in the dorsal segment of the eye (

Fig. 119.1). The retina, consisting of seven layers of cells and fibers, lines the interior surface of the eye and converts light into a neural signal. The temporal visual field is perceived by the nasal hemiretina while the nasal visual field falls on the temporal hemiretina. The retinal nerve fiber layer collects into the optic nerve and transmits this visual signal to the occipital cortex (

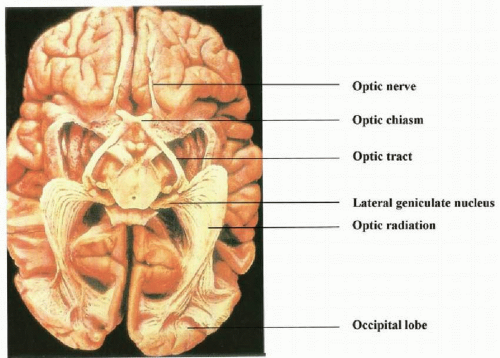

Fig. 119.2).

The optic nerve exits the globe through the lamina cribrosa, travels in the optic canal, and acquires a dural sheath at this location. This allows free circulation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) around the optic nerve. The optic canal begins at the apex of the bony orbit, transmits the optic nerve and ophthalmic artery, and lies within the sphenoid bone. The intracranial segments of each optic nerve coalesce into the optic chiasm. Within the chiasm, there is a decussation of the nasal retinal fibers (temporal visual field) from each nerve, which join the uncrossed temporal retinal fibers (nasal visual field) of the other eye and continue on as the optic tracts.

The optic tracts terminate at their respective lateral geniculate bodies. The lateral geniculates, located in the dorsal thalami, group the incoming fibers into layers based on spatial and color perception versus motion detection. After synapsing here, the axons travel dorsally in the brain as optic radiations and terminate in the primary visual cortex in the occipital lobe. The primary visual area (V1, striate cortex, Brodmann area 17) sits along the horizontal calcarine fissure, which divides the medial surface of the occipital lobe.

VASCULAR SUPPLY

The main blood supply to the occipital lobes is through the middle and posterior cerebral arteries. The intrac-ranial optic nerves and the chiasm are supplied by small branches of the proximal anterior cerebral artery and anterior communicating artery.

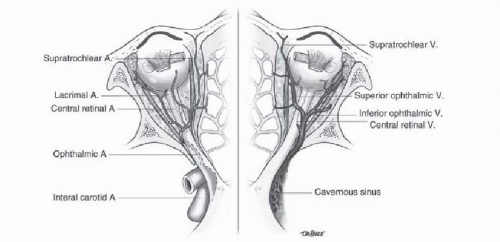

Upon emerging from the cavernous sinus, the internal carotid artery gives off the ophthalmic artery (

Fig. 119.3), which then enters the orbit through the optic canal. The ophthalmic artery then gives off the central retinal artery approximately 10 mm dorsal to the globe. Thus, most of the blood supply to the optic nerve comes from the ophthalmic artery via pial branches of the surrounding arachnoid. The central retinal artery and vein travel within the ventral 10 mm of the optic nerve and enter the eye.

The central retinal artery is responsible for supplying the ventral two-thirds of the retina. The terminal ophthalmic artery gives additional branches that form the posterior ciliary arteries, supplying the dorsal third of the retina, choroid, and optic disk. In approximately 30% of individuals, the posterior ciliary arteries also supply a portion of the inner retina as the cilioretinal arteries. These individuals can retain their macular and central vision despite a CRAO.