6 Organic psychiatry

Introduction

In ICD-10 organic mental disorders are grouped on the basis of a common demonstrable aetiology being present in the form of cerebral disorder, injury to the brain or other insult leading to cerebral dysfunction (Table 6.1). The cerebral dysfunction may be:

Table 6.1 ICD-10 classification: F00–F09 Organicorganic, including symptomatic, mental disorders

| F00 Dementia in Alzheimer’s disease |

| F01 Vascular dementia |

| Includes multi-infarct dementia and subcortical vascular dementia. |

| F02 Dementia in other diseases classified elsewhere |

| Includes dementia in Pick’s disease, Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, Huntington’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease. |

| F03 Unspecified dementia |

| F04 Organic amnesic syndrome, not induced by alcohol and other psychoactive substances |

| F05 Delirium, not induced by alcohol and other psychoactive substances |

| F06 Other mental disorders due to brain damage and dysfunction and to physical disease |

| Includes organic hallucinosis, organic catatonic disorder, organic delusional (schizophrenia-like) disorder, organic mood (affective) disorders, organic anxiety disorder, organic dissociative disorder, organic emotionally labile (asthenic) disorder, and mild cognitive disorder. |

| F07 Personality and behavioural disorders due to brain disease, damage and dysfunction |

| Includes organic personality disorder, postencephalitic syndrome and postconcussional syndrome. |

| F09 Unspecified organic or symptomatic mental disorder |

Psychological dysfunction

The disorders described in this chapter result in psychological dysfunction in one or more of the following areas (see also Chapter 5):

Classification

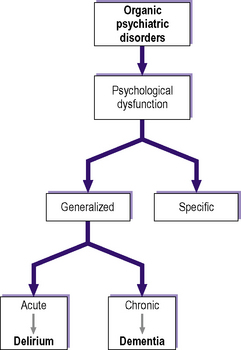

In this chapter organic psychiatric disorders are classified according to whether they cause generalized psychological dysfunction or specific impairment in just one or two areas (e.g. thinking and mood) (Figure 6.1). Some disorders may cut across this classification. For example, at various stages in the course of its natural history, a brain tumour may cause psychological dysfunction that is acute and generalized (delirium), specific, and chronic and generalized (dementia).

Clinical aspects

Organic psychiatric disorders lie at the apex of the diagnostic hierarchy (see Figure 3.2). In other words, they should be excluded before a diagnosis of a ‘functional’ psychosis, neurosis or personality disorder is entertained. For example, if a young man were to present for the first time with symptoms typically seen in schizophrenia, such as Schneiderian first-rank symptoms (see Chapter 8), it would be important to exclude the possibility that the symptoms resulted from an organic psychiatric disorder or psychoactive substance abuse, before treating the patient for schizophrenia. It could be that his symptoms were the result, for instance, of temporal lobe epilepsy or amphetamine abuse. Similarly, a middle-aged woman presenting with low mood may in fact be suffering from a brain tumour, hypothyroidism or Addison’s disease, rather than a depressive illness. When such a primary organic cause is found, it should be the primary focus of treatment; in many cases it may be reversible.

History

Mental state examination

If an organic disorder is suspected it is important to carry out a detailed cognitive assessment including tests for apraxias, agnosias and language ability (see Chapter 5).

Physical examination

A detailed physical examination should be carried out if an organic psychiatric disorder is suspected. Together with the history and mental state examination, this may give a strong indication of the nature of the underlying pathology before any investigations are performed. For example, the presence of increased pigmentation in the mouth, skin creases and pressure points of a patient complaining of an insidious onset of low mood and lassitude points to Addison’s disease. Similarly, in a young person presenting for the first time with auditory hallucinations, the presence of venepuncture marks points to the possibility that illicit drug abuse may be the underlying cause, although the relationship between drug use and psychiatric illness is not straightforward (see Chapter 7).

Investigations

The routine investigations detailed in Chapter 5 should be carried out: i.e. further information should be obtained from the GP, relatives and the case notes from any previous hospital treatment; routine haematological and biochemical tests, such as thyroid function tests; other blood tests as cited in Chapter 5 (such as syphilitic serology). In addition, other investigations should be carried out as appropriate: for example, cortisol assay in suspected Addison’s disease, electroencephalography (EEG) in suspected epilepsy, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) in suspected brain malignancy, and neuropsychological testing in suspected dementia or pseudodementia.

Delirium

Clinical features

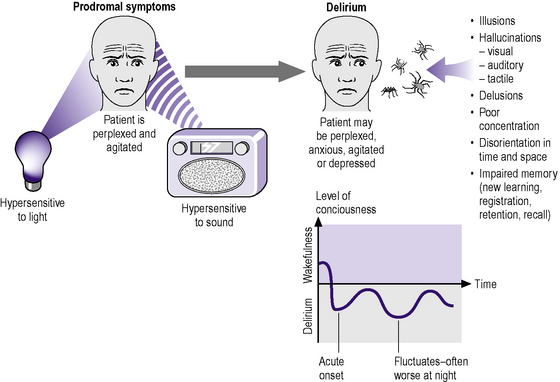

The clinical features of delirium are summarized in Figure 6.2. Prodromal symptoms include:

Features of delirium itself include the following:

Epidemiology

Delirium can occur in patients suffering from physical illnesses, particularly hospital inpatients:

Aetiology

Delirium can result from poisoning, psychoactive substance-use withdrawal, intracranial causes, endocrinopathies, metabolic disorders, systemic infections and postoperatively. Details of these causes, including psychoactive substance use (see Chapter 7), are summarized in Table 6.2. This is an appropriate place to consider briefly the more important clinical features of some of these endocrinopathies, particularly those that often present with psychiatric symptoms other than delirium.

| Drugs and alcohol | Drug toxicity – antimuscarinic (anticholinergic) drugs, anticonvulsants, antihypertensives, anxiolytic-hypnotics, cardiac glycosides, cimetidine, insulin, levodopa, opiates, salicylate compounds, steroids; industrial poisons (e.g. organic solvents and heavy metals); carbon monoxide poisoning |

| Intracranial causes | Infections – encephalitis, meningitis |

| Head injury | |

| Subarachnoid haemorrhage and space-occupying lesions – e.g. brain tumours, abscesses, subdural haematomas | |

| Epilepsy and postictal states | |

| Drug and alcohol withdrawal – withdrawal of anxiolytic-sedative drugs, amphetamine | |

| Metabolic and endocrine disorders | Endocrinopathies – Addison’s disease, Cushing’s syndrome, hyperinsulinism, hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, hypopituitarism, hypoparathyroidism, hyperparathyroidism |

| Systemic infections | Hepatic failure, renal failure, respiratory failure, cardiac failure, pancreatic failure |

| Postoperative states | Hypoxia |

| Hypoglycaemia | |

| Fluid and electrolyte imbalance | |

| Errors of metabolism – carcinoid syndrome, porphyria | |

| Vitamin deficiency – thiamine, nicotinic acid, folate, vitamin B12 |

Primary hypoadrenalism (addison’s disease)

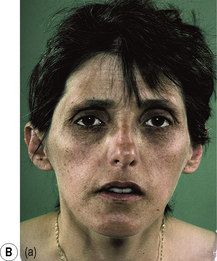

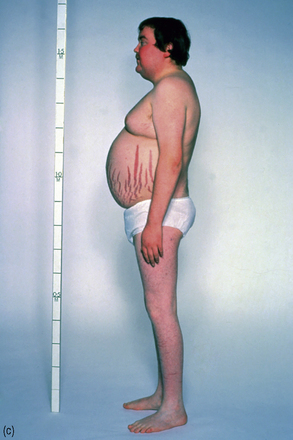

There is destruction of the adrenal cortex in this relatively uncommon endocrine disorder, leading to reduced production of glucocorticoids, mineralocorticoids and sex steroids. This condition often presents with symptoms similar to those that occur in depression, including weakness, tiredness, weight loss, depressed mood and anorexia. Important clinical features are shown in Figure 6.3(a) and (b).

Figure 6.3 • Clinical features of primary hypoadrenalism (Addison’s disease).

(A) Bold type indicates signs of greater discriminant value.

(Reproduced with permission from Kumar P, Clark M (eds) 1998 Clinical medicine. WB Saunders, Edinburgh.)

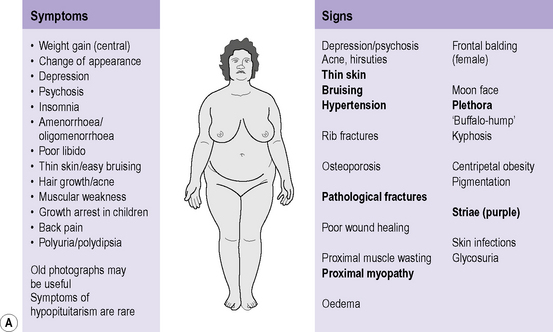

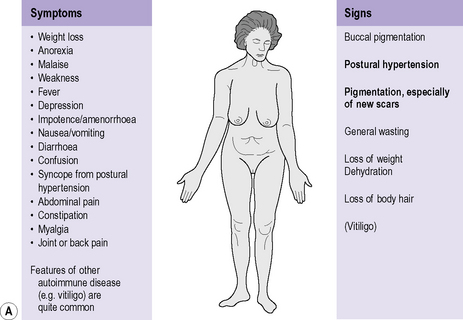

Cushing’s syndrome

Cushing’s syndrome may present with symptoms similar to those seen in depression, mania and schizophrenia (including mood changes, delusions, hallucinations and thought disorder). Important clinical features are shown in Figure 6.4(a) and (b).

Figure 6.4 • Clinical features of Cushing’s syndrome.

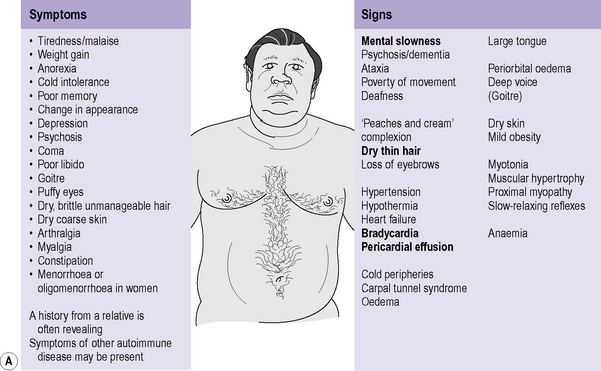

Hypothyroidism

This is one of the most common endocrine disorders (particularly in women). Causes include:

Hypothyroidism may present with symptoms similar to those seen in depression, mania and schizophrenia (myxoedema madness). Important clinical features are shown in Figure 6.5(a) and (b). Note that these features may not be seen in children and young women. The former often have slowed growth and perform poorly at school; pubertal development may be arrested. This condition should be excluded in any young non-pregnant, non-postpartum woman presenting with:

Figure 6.5 • Clinical features of hypothyroidism.

(A) Bold type indicates signs of greater discriminant value.

(Reproduced with permission from Kumar P, Clark M (eds) 1998 Clinical medicine. WB Saunders, Edinburgh.)

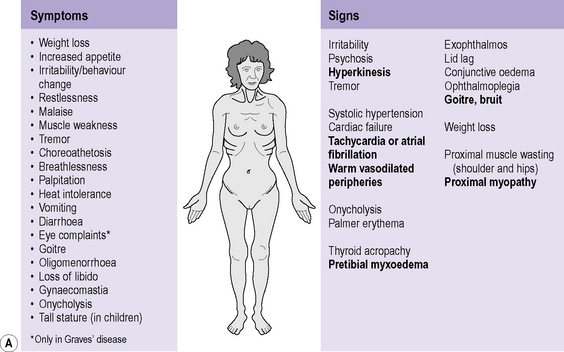

Hyperthyroidism

This is one of the most common endocrine disorders (particularly in women). Causes include:

Hyperthyroidism may present with symptoms similar to those seen in mood disorders, panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder and, in children, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (behavioural problems such as hyperactivity). Important clinical features are shown in Figure 6.6(a) and (b). Note that these features may not be seen in children, in whom hyperthyroidism may instead manifest as excessive growth or behavioural problems.

Figure 6.6 • Clinical features of hyperthyroidism.

(A) Bold type indicates signs of greater discriminant value.

(Reproduced with permission from Kumar P, Clark M (eds) 1998 Clinical medicine. WB Saunders, Edinburgh.)

Management and prognosis

In patients who are very agitated, anxious or frightened, oral or intramuscular haloperidol can be used; if there is hepatic failure then benzodiazepines can be given. Benzodiazepines can also be given for their hypnotic effect at night. The treatment of alcohol withdrawal is described in Chapter 7.

Dementia

Dementia is characterized by generalized psychological dysfunction of higher cortical functions without impairment of consciousness. In fully developed dementia the higher cortical functions affected include memory, thinking, orientation, comprehension, calculation, learning capacity, language and judgement. Dementia is an acquired and usually chronic or progressive disorder, although sometimes it may be reversible. In most sufferers the cause (e.g. Alzheimer’s disease) is currently incurable; management strategies are discussed in Chapter 20.

Clinical features

Higher cortical functions

Higher functions that may become impaired in dementia include:

In order to elicit the above clinical features it is particularly important to carry out a detailed mental state examination, including a full cognitive assessment (see Chapter 5), and to obtain further information from informants. Table 6.3 compares the features of delirium with those of dementia.

Table 6.3 Comparison of features of delirium and dementia

| Delirium | Dementia |

|---|---|

| Acute onset | Insidious onset |

| Disorientation, bewilderment, anxiety, poor attention | |

| Clouding of/impaired consciousness, e.g. drowsy | Clear consciousness |

| Perceptual abnormalities (illusions, hallucinations) | Global impairment of cerebral functions (e.g. recent memory, intellectual impairment and personality deterioration with secondary behaviour abnormalities) |

| Paranoid ideas/delusions (term delirium sometimes only used if delusions and/or hallucinations present) | |

| Fluctuating course with lucid intervals | Progressive course (static course in head injury and brain damage) |

| Reversible | Irreversible |

Aetiology

The causes of dementia are summarized in Table 6.4. Alzheimer’s disease and vascular (including multi-infarct) dementia together account for approximately three-quarters of all cases of dementia. They are described in more detail in this section, with other specific causes of dementia: Lewy body dementia, frontotemporal dementia, Pick’s disease, Huntington’s disease (chorea), Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease and normal-pressure hydrocephalus. Other disorders that can result in dementia, for example Parkinson’s disease, are described in the next section of this chapter and in Chapter 7.

| Degenerative diseases of the CNS | Alzheimer’s disease |

| Pick’s disease | |

| Huntington’s disease (or chorea) | |

| Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease | |

| Normal-pressure hydrocephalus | |

| Parkinson’s disease | |

| Multiple sclerosis | |

| Lewy body disease | |

| Intracranial causes | Space-occupying lesions – tumours, chronic subdural haematomas, chronic abscesses, aneurysms |

| Infections – encephalitis, meningitis, neurosyphilis, AIDS and AIDS-related complex (ARC), cerebral sarcoidosis | |

| Trauma – head injury, punch-drunk syndrome | |

| Metabolic and endocrine disorders | Endocrinopathies – Addison’s disease, Cushing’s syndrome, hyperinsulinism, hypothyroidism, hypopituitarism, hypoparathyroidism, hyperparathyroidism |

| Hepatic failure, renal failure, respiratory failure | |

| Hypoxia | |

| Renal dialysis | |

| Chronic uraemia | |

| Chronic electrolyte imbalance – hypocalcaemia, hypercalcaemia, hypokalaemia, hyponatraemia, hypernatraemia | |

| Porphyria | |

| Hepatolenticular degeneration (Wilson’s disease) | |

| Vitamin deficiency – thiamine, nicotinic acid, folate, vitamin B12 | |

| Vitamin intoxication – vitamin A, vitamin D | |

| Paget’s disease | |

| Remote effects of carcinoma or lymphomas | |

| Vascular causes | Multi-infarct dementia |

| Cerebral artery occlusion | |

| Cranial arteritis | |

| Arteriovenous malformation | |

| Binswanger’s disease | |

| Intoxication | Alcohol |

| Heavy metals – lead, arsenic, mercury, thallium | |

| Carbon monoxide | |

| Drug and alcohol withdrawal – withdrawal of anxiolytic-sedative drugs, amphetamine |

Alzheimer’s disease

Pathological features

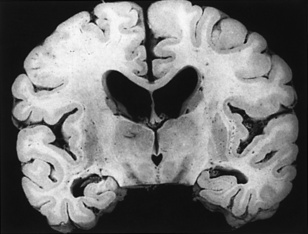

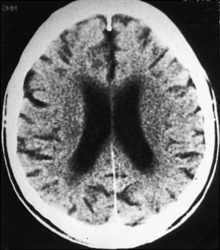

Macroscopically there is global atrophy of the brain, which is shrunken with widened sulci and ventricular enlargement. The atrophy is usually most marked in the frontal and temporal lobes, as shown in Figure 6.7. The structural neuroimaging appearances seen are shown in Figure 6.8.

Figure 6.7 • Alzheimer’s disease.

(Reproduced with permission from Graham DI, Nicoll JAR, Bone I (eds) 2006; see Further reading.)

Figure 6.8 • Alzheimer’s disease seen on CT scan.

(Reproduced with permission from Suohami RL, Moxhum J (eds) 1994 Textbook of medicine, 2nd edn. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh.)

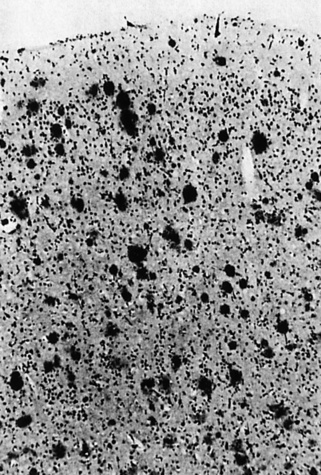

Histologically there is neuronal loss, shrinkage of dendritic branching and a reactive astrocytosis in the cerebral cortex. Other neuropathological features include the abundant presence, particularly in the cerebral cortex, of neurofibrillary tangles; the presence, mainly in the cortex, of silver-staining neuritic plaques (senile plaques) (Figure 6.9); granulovacuolar degeneration, particularly in the middle pyramidal layer of the hippocampus; and eosinophilic rod-shaped filamentous intracytoplasmic neuronal inclusion bodies known as Hirano bodies. Neurofibrillary tangles are silver-staining highly insoluble neuropathological structures of the neuronal perikaryon, made up of thick bundles of neurofibrils. The numbers of neurofibrillary tangles and neuritic plaques correlate with the degree of cognitive impairment.

Figure 6.9 • Alzheimer’s disease.

(Reproduced with permission from Graham DI, Nicoll JAR, Bone I (eds) 2006; see Further reading.)

Clinical features

Alzheimer’s disease is more common in women and in those with a family history of:

Patients with Down’s syndrome are very likely to develop the neuropathology and clinical features of Alzheimer’s disease by the time they reach the fourth decade (see Chapter 17). This is probably related to the fact that Down’s syndrome results from trisomy 21.

Lewy body dementia

Lewy body dementia is the second most common neurodegenerative cause of dementia.

Pathological features

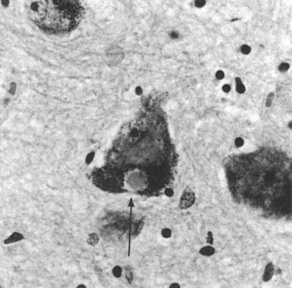

The histological appearance of a typical Lewy body is shown in Figure 6.10. A Lewy body is an intracytoplasmic concentrically laminated round to elongated eosinophilic inclusion, which often has a dense central core surrounded by a paler peripheral rim.

Figure 6.10 • Lewy body in Parkinson’s disease.

(Reproduced with permission from Graham DI, Nicoll JAR, Bone I (eds) 2006; see Further reading.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree