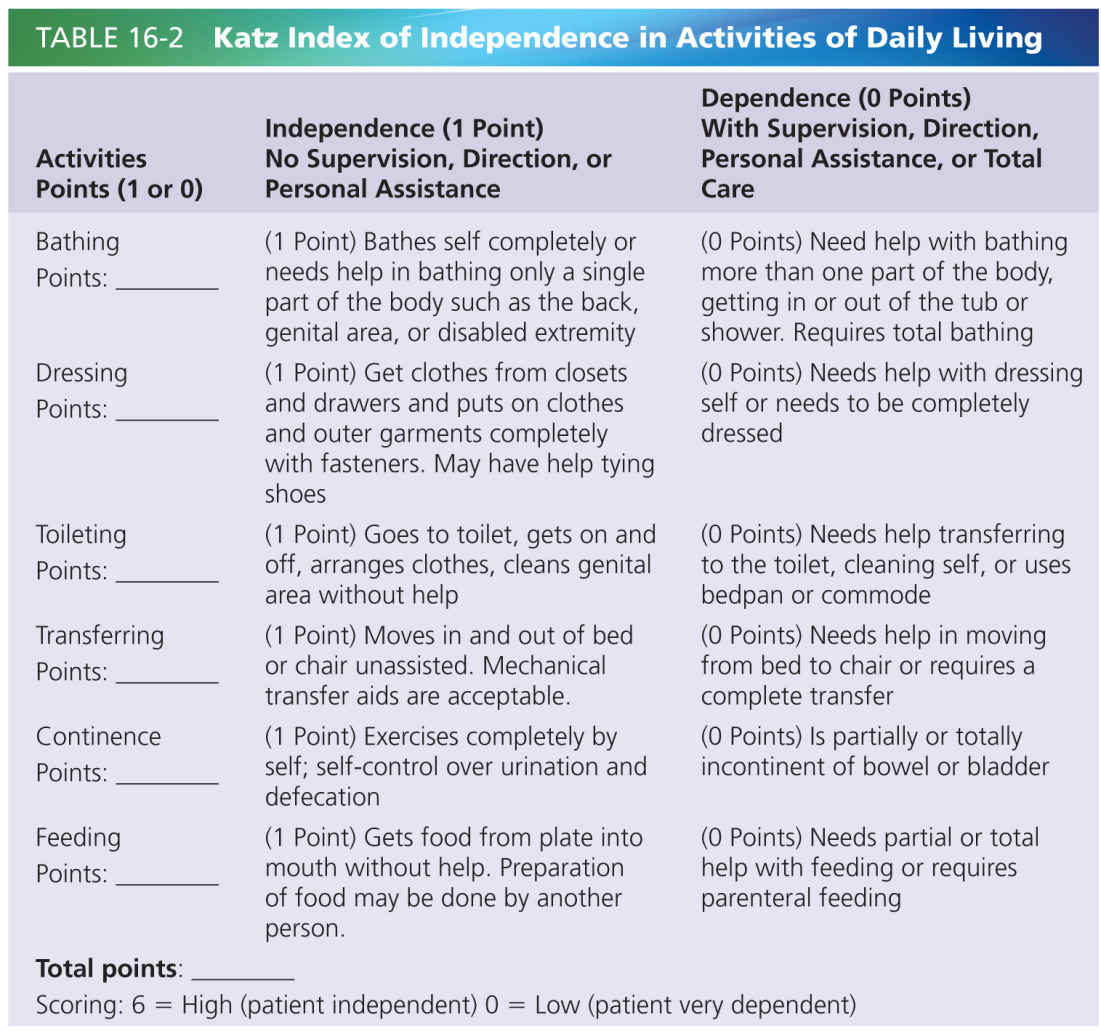

ADL refer to daily self-care activities, such as bathing, personal hygiene and grooming, toilet hygiene, walking, and eating. There are several measurement instruments for measuring ADL function. What particular function is considered an ADL function highly depends on the instrument used (examples: Barthel index [27] and Katz index [17], see Tables 16-1 and 16-2).

IADL: Instrumental Activities of Daily Living

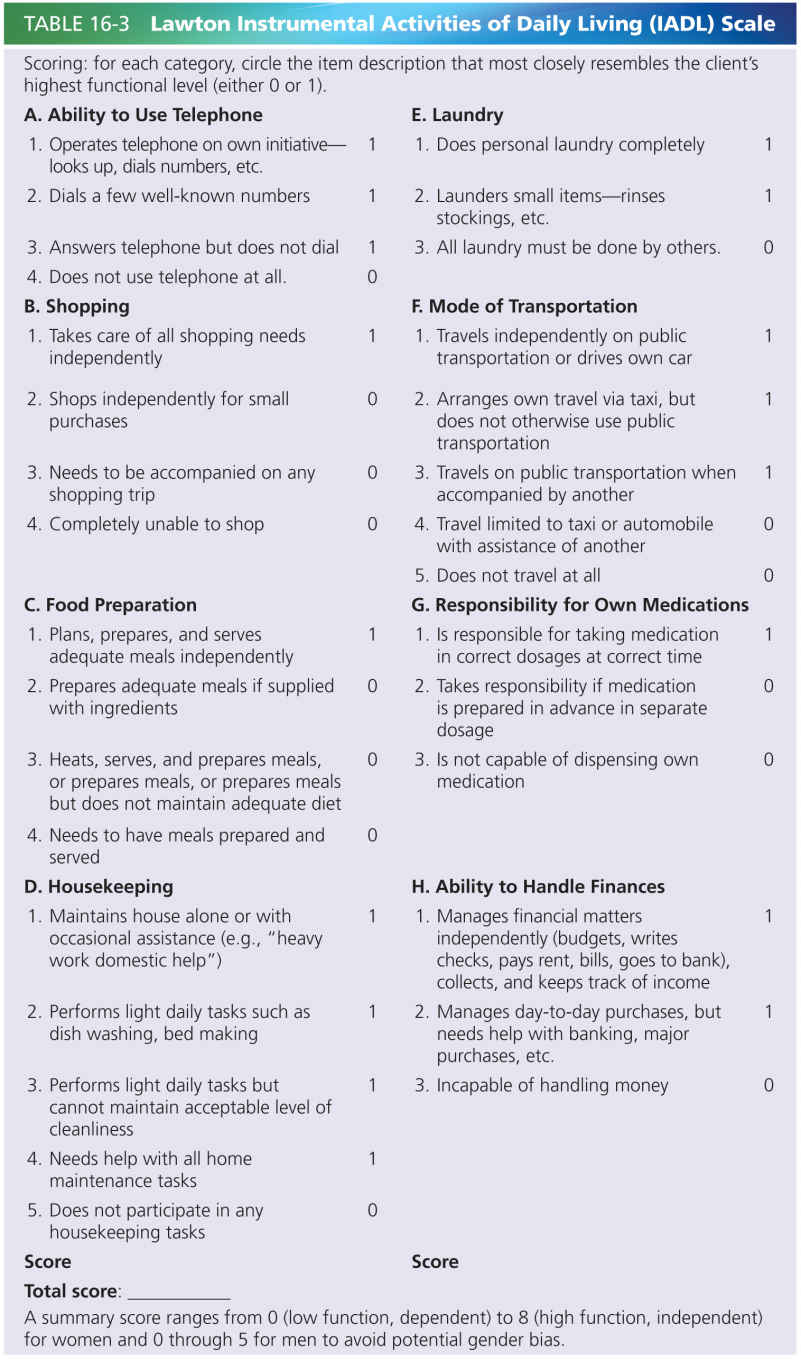

IADL are not strictly necessary for basic day-to-day functioning, but are more or less important to live independently in the community. These functions include shopping, housekeeping, accounting, food preparation, use of communication devices such as telephone and computer, but also transportation and doing the laundry.

There are several evaluation tools, such as the Lawton IADL scale [20]; see Table 16-3.

Functions, Activities, and Participation: The ICF Model

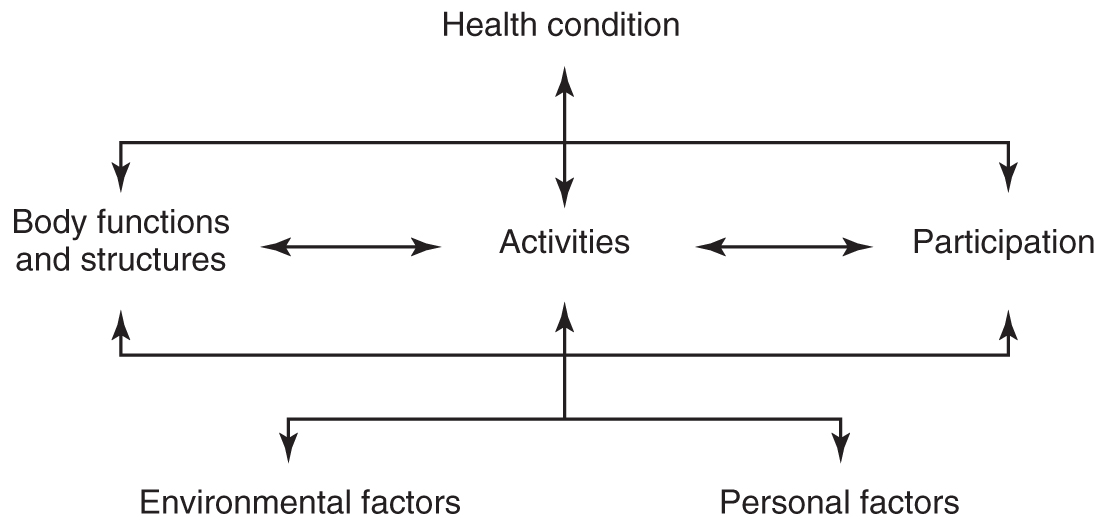

The most widely used model to look at consequences of diseases or afflictions such as arthritis, stroke, or pain is the ICF, which was proposed by the WHO (see Fig. 16-1). In this model, a specific health problem influences functions (e.g., moving a leg), activities (e.g., walking), and participation (e.g., shopping or visiting a relative). It also clarifies, that the strength of the consequences on function, activity, and participation is mediated by other factors, which are related to the individual itself, for instance culture (see Chapter 25) and coping strategies, but also the environment, for instance the presence of a spouse and the presence of formal care [46].

FIGURE 16-1 The International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF), a framework for describing and organizing information on functioning and disability, WHO [46]. It provides a standard language and a conceptual basis for the definition and measurement of health and disability.

FUNCTIONAL IMPAIRMENT AND DEMENTIA IN THE ICF MODEL

Dementia in itself leads to progressive impairment at each level of the ICF model (function, activities, participation). With disease progression of most subtypes of dementia, participation in general is mostly the first to be impaired because participation functions (such as shopping, visiting friends, work, driving a car) are the most complex activities, requiring complex cognitive tasks skills. In other words, participation tasks heavily rely on higher and more complex cortical functions that are affected early in the disease. Activities and functions are in the course of the disease the next to suffer from the neuropathological changes, affecting the function balance and mobility (leading to falls), and increasing dependence in simple activities, such as bathing and clothing. Apraxia can lead to difficulties in handling even simple tools, such as a knife and fork or a comb. In the end phase of the disease, also simple functions such as moving a limb, urinary and fecal continence, chewing and swallowing are affected.

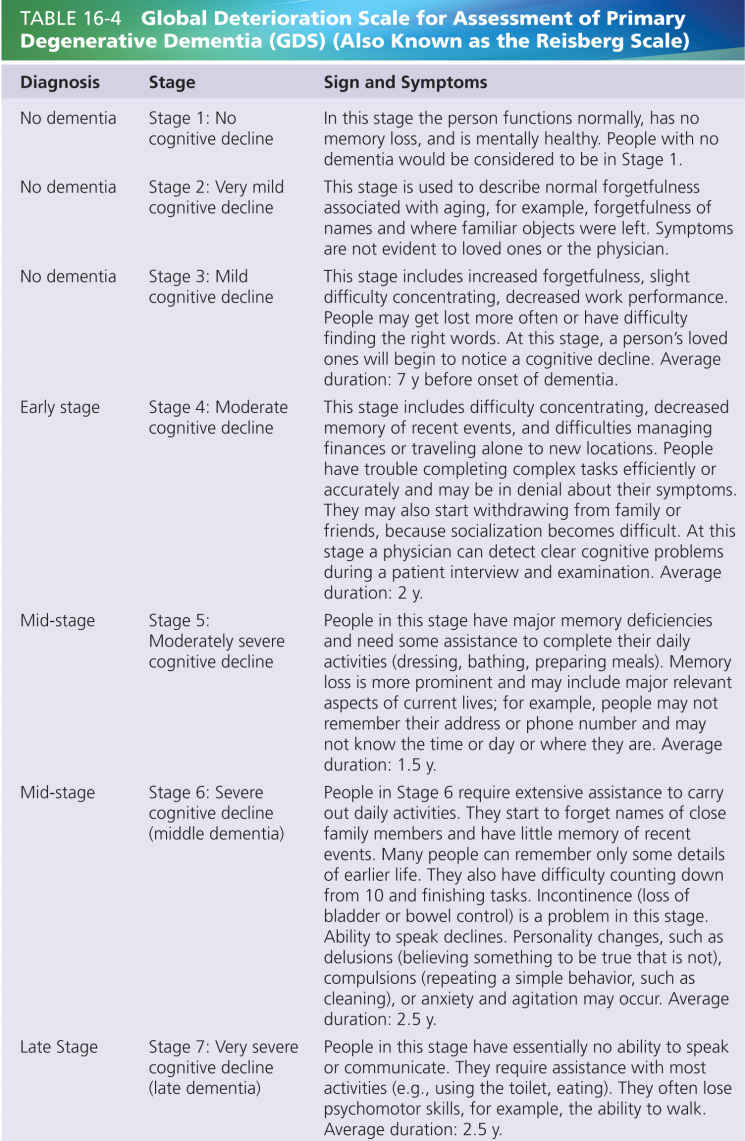

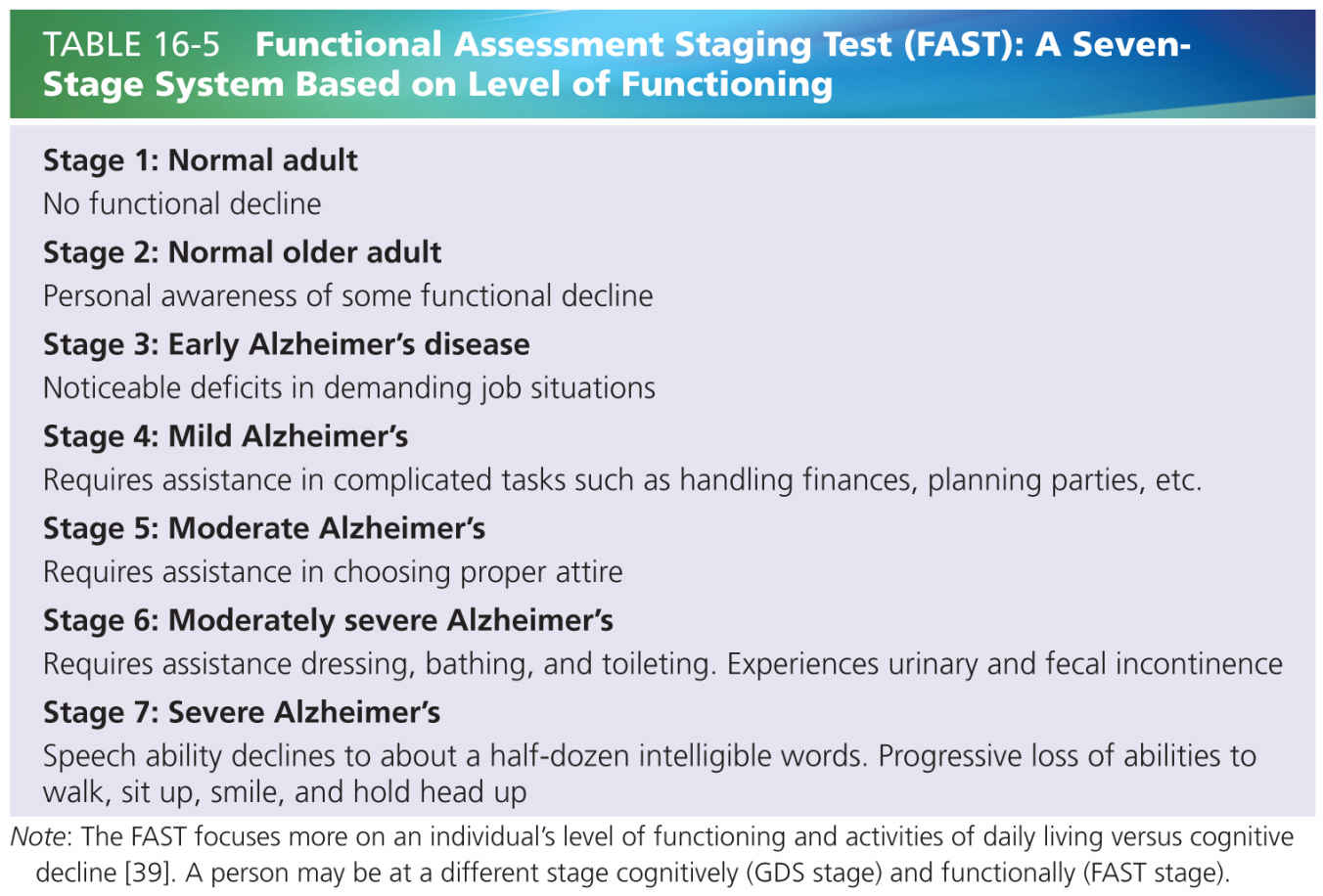

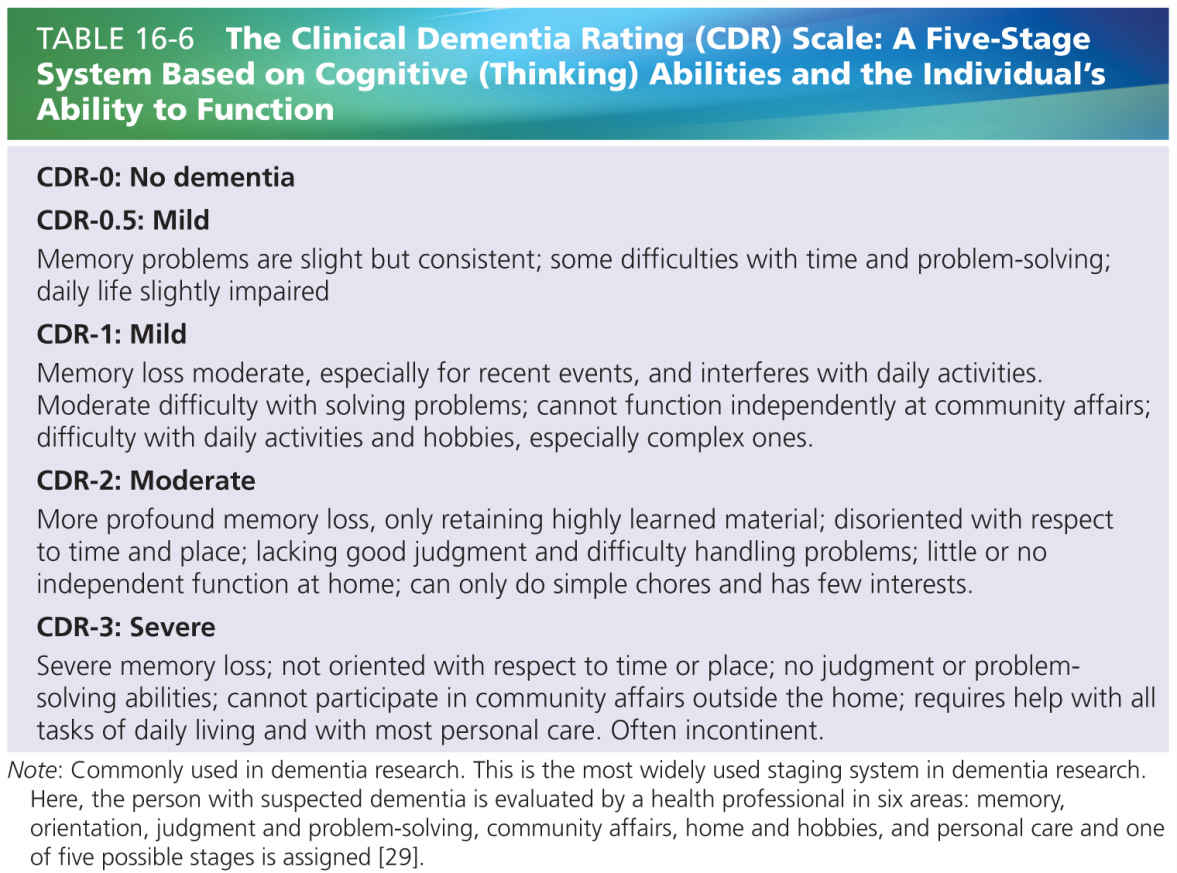

While the degree of cognitive impairment can be measured with instruments like the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [12], the severity of the dementia is best measured with instruments that combine cognitive and functional performance. Good examples are the Reisberg Global Deterioration Scale (GDS) [32], the Functional Assessment Staging of Alzheimer’s Disease (FAST) [39], or Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) [29] (see Tables 16-4, to 16-6). On the other hand, it is argued that cognitive decline and functional decline do not always go hand in hand and that functioning is best measured separately, also because cognitive impairment is not the only explanation for functional impairment [11]. (See also paragraph “Measurement Instruments for Function, Activities, and Participation in Dementia” further on.)

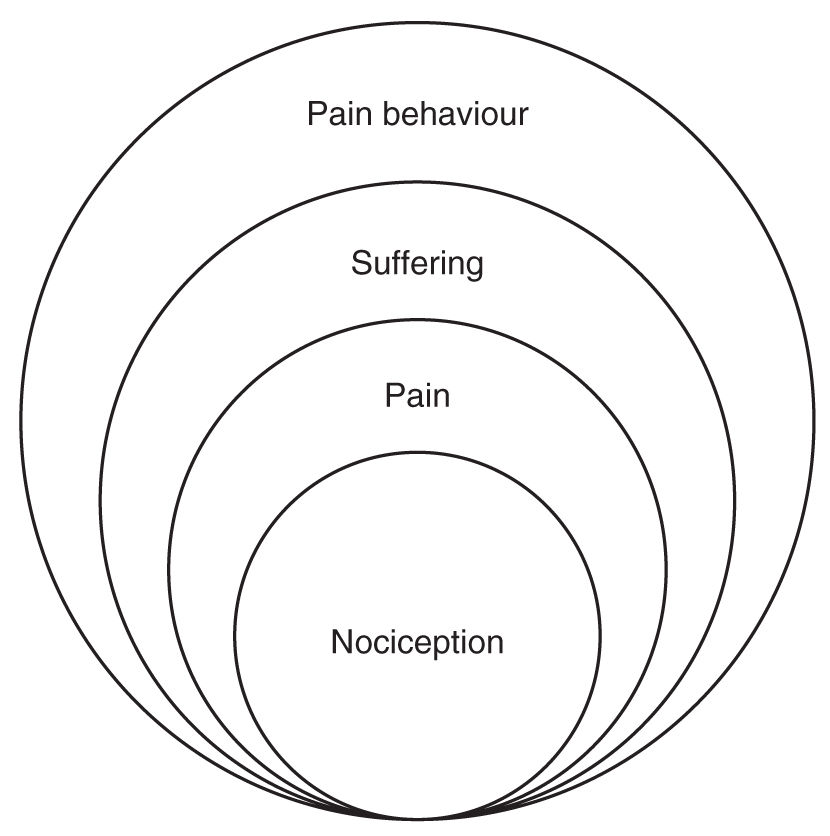

FIGURE 16-2 Loeser’s biopsychosocial model of pain.

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PAIN AND FUNCTIONAL IMPAIRMENT: THE BIOPSYCHOSOCIAL MODEL

The biopsychosocial model of pain by Loeser [22, 23] (see Fig. 16-2) has had a tremendous influence on both pain researchers and pain clinicians. One of the strengths of this model is that it provides an explanatory concept why similar nociceptive stimuli can have different effects on activities and participation in different individuals. In pain research and pain management and rehabilitation practice, especially the pathway to chronic pain and persistent functional impairment (leading to, for instance, the inability to work) is being studied as it has enormous societal, medical, and economic impact. In general, this pathway is as follows: pain may lead to fear of performing certain functions, activities, and participation, and consequently to avoidance of those functions, activities, and participation, which in consequence can lead to persistent disablement. It is however not known if this also applies to persons with dementia.

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PAIN AND FUNCTIONAL IMPAIRMENT IN PEOPLE WITHOUT DEMENTIA

Next to the fact that pain in general can lead to avoidance of activities which trigger the pain, pain in older people without dementia is known to have a negative relationship with the person’s physical functioning, including sleeping, eating, and mobility [13, 48]. Moreover, not pain in itself but pain that has consequences on daily functioning will often be the reason to seek help and start treatment.

The relationship of pain with decreased physical functioning is quite strong. The risk of disability and impairment of mobility also is known to increase with the number of painful (musculoskeletal) areas reported [5, 40]. Immobility and avoidance lead to decreased activity and use of muscles, which is a risk factor for (more) pain. This pathway to chronic pain and disability has been described extensively but especially in patients without dementia. It not only provides explanations but also helps to identify targets for treatment. As described above with the model of Loeser, the attitudes and beliefs of older people without dementia influence all aspects of their pain experience, including the effect of pain on functional impairment, and also play an important role in whether and how patients will engage with treatment [1].

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PAIN AND FUNCTIONAL IMPAIRMENT IN PEOPLE WITH DEMENTIA

In people with dementia, it is not expected that attitudes and beliefs have a large influence on the relation between pain and functional impairment. But there are other circumstances that influence the relationship between pain and functional impairment.

First, there is a strong relationship between cognitive impairment (or better: advancing neuropathological changes) and functional impairment. Dementia leads to functional impairment, following the progressive nature of the disease.

Second, persons with dementia experience the effects of both formal and informal caregivers to their health status. When the reaction of the (formal and informal) caregivers is one that tries to be protective and to provide comfort to the persons with dementia, then the avoidance of potential painful activities can be potentiated and independent behavior discouraged. Although this is also the case in patients with other chronic or progressive diseases, this effect in dementia might be larger because the loss of competence that a person with dementia experiences tends to increase the protective behavior of caregivers. This is in line with the operant theory of chronic pain by Fordyce.

Therefore, it is interesting to see what evidence exists on the relationship between pain and functional impairment in people with dementia.

Relationship between Pain and Function in Dementia: Existing Evidence from Cross-Sectional Studies on Pain and Function

Based on a 2014 systematic literature review (van Dalen-Kok et al, 2015), only a small number of studies were identified that describe a relationship between pain and functional limitations in older persons with moderate to severe dementia, like ADL or IADL impairment (six studies), limited mobility or reduced activity/ambulatory status (three studies), and malnourishment (two studies). Interestingly, only few articles report a significant association of pain with functional impairment [21, 41]. The other studies showed no or only weak correlations of pain with functioning. Although one might therefore draw the conclusion that pain is not or only weakly correlated with functional limitations in persons with dementia, we question whether this is appropriate. There is reasonable doubt whether these cross-sectional studies were capable of disentangling the complex relationship between dementia-related and pain-related effects on functional impairment. Interestingly, the study by Lin et al. [21] did find a strong relationship but was different from all the other regular cross-sectional studies. Pain was observed by professionals with the Chinese version of the PAINAD, immediately following instances of routine care. The observed care activities were bathing, assisted transfer from bed to wheelchair, or self-transfer from bed to walking. Pain was observed far more frequently during bathing or assisted transfer than in self-transfer situations: during self-transfer observations, only 1 out of 29 residents (3%) was in pain, whereas during bathing 46% and during assisted transfer 51%. Possibly, pain in dementia is more related to specific functional impairment that is difficult to find using more general functional measurement scales. Cipher [7] used path analyses to study the directional influences between cognitive, emotional, and behavioral disturbances and ADLs among residents living in long-term care facilities in the USA. A total of 63% had moderate dementia. The study showed an indirect effect of pain on ADL: pain levels influenced behavioral disturbances and depression, which in turn influenced ADL. One study looked at the activity status [47] and another at the ambulatory status of residents [10]. Again, both found no direct associations between pain and activity or ambulatory status.

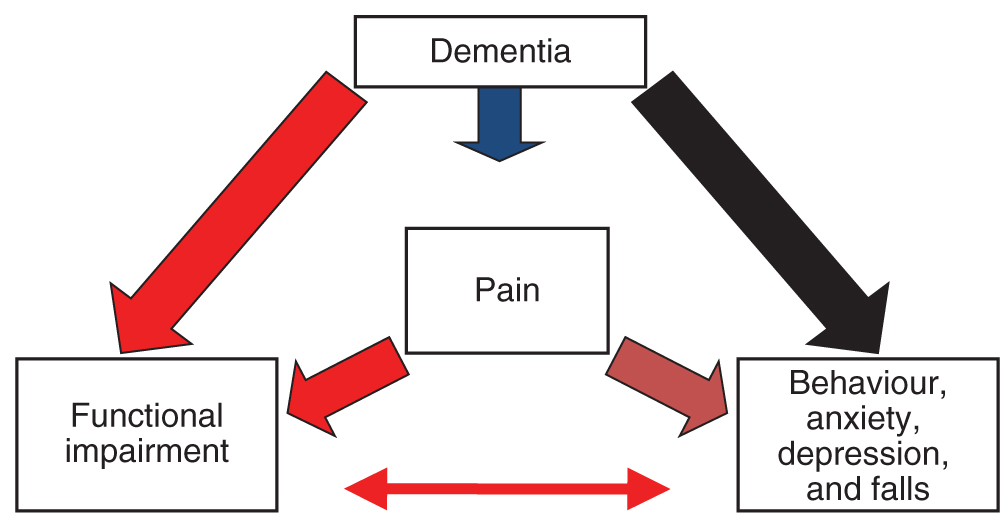

FIGURE 16-3 A schematic model for developing functional impairment in pain and dementia: impairment is directly caused by neuropathological changes in dementia, and by painful conditions or central pain. To a lesser extent, functional impairment is also related to indirect consequences of both pain and dementia: behavioral problems (such as apathy), anxiety, depression and falls, and indirect consequences of these behaviors (physical restraints, psychotropic medication).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree