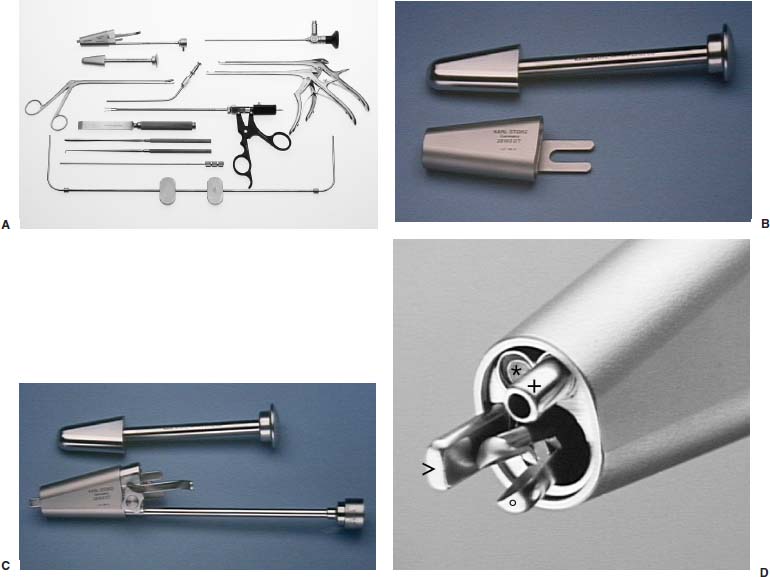

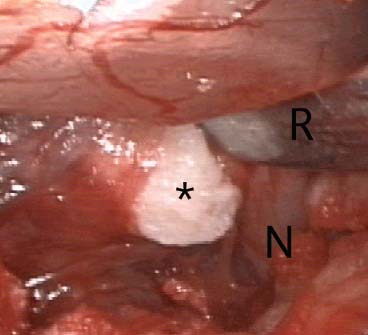

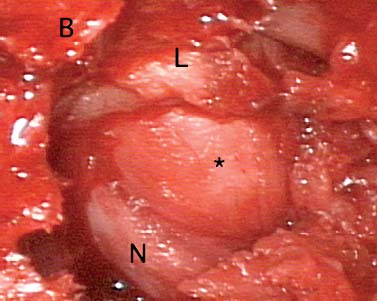

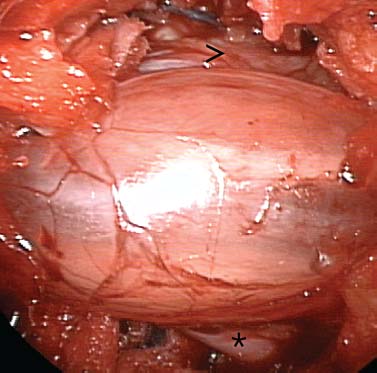

There is no doubt that the future of surgery lies in the development of minimally invasive techniques, and that spinal surgery does not escape this rule. This belief prompted the development by the author of special instrumentation to facilitate posterior endoscopic surgery,1 first for prolapsed lumbar disks, and then for lumbar spinal canal stenosis. This instrumentation was custom-designed in 1993 to resolve two key difficulties presented by endoscopic surgery for disk herniation in the lumbar region. First, the instrument creates a working space mechanically rather than by the use of a fluid under pressure, which was unacceptable given the danger that such pressure would represent for the neural elements. Second, the angle between the working channel and the optics channel provides the triangulation necessary to keep the extremity of the instruments constantly in view to facilitate the operation. Prototypes of the device were used until 1998, when standard instrumentation (Karl Storz GmbH & Co., Tuttlingen, Germany) became available. Indications The posterior endoscopic approach of the spine can be used in all types of lumbar disk herniations, including lateral or recurrent disk herniations, lumbar spinal stenosis (central or lateral), and soft lateral cervical and thoracic disk prolapses. Contraindications This endoscopic approach is contraindicated in cases of calcified midline thoracic herniations. Instruments The Endospine (Karl Storz) consists of a small speculum provided with an inserter that penetrates the superficial layers, bringing the speculum into contact with the lamina. The inserter is then removed, and the surgeon slides a device into the speculum housing three tubes, one for the endoscope (4 mm in diameter), another for the suction cannula (4 mm in diameter), and the largest for the surgical instruments (9 mm in diameter) (Fig. 21–1). The first two are parallel, whereas the third is at an angle of 12 degrees to them; thus, the tubes generally converge in the plane of the posterior longitudinal ligament. This angulation enables the surgeon to keep the ends of the instruments in view at all times and to use the suction cannula as a second instrument. The system also includes a nerve root retractor that can be pushed into the spinal canal and used to retract the nerve root medially, thus clearing the operative field of any fragile structure. Surgical Technique The intervention is typically performed under general anesthesia, with the patient in the knee-chest position on the operating table. The surgical technique itself is classic and begins with a posterior approach to the spinal canal between the muscles and the lamina. Marking the Point of Entry With the aid of a special device with two arms (Karl Storz), the point of entry and the direction of approach to the disk space are determined under fluoroscopic control (Fig. 21–2). FIGURE 21–1 (A) Endospine operating system with various endoscopic instruments. (B) The speculum and its inserter. (C) The inner part housing three tubes. (D) The tip of the system, with the suction (+), the endoscope (*), a pituitary forceps (°), and the nerve-root retractor (>) indicated. Skin Incision and Approach At the mark left on the skin, the surgeon makes a 15 to 20 mm incision. The aponeurosis is sectioned with dissecting scissors. The underlying paravertebral muscles are progressively retracted. Bipolar coagulation is used to stop any bleeding. Through the access, a 12 mm osteotome is inserted down to the lamina. Dilation of the Soft Tissues with the Operating Cone The operating cone with its cap is inserted down to the lamina. The cap is then removed. Any soft tissue bulging into the operating cone is excised. Preparation of the Tool Sheath The tool sheath is then placed in the operating cone and attached to it with a screw. The suction cannula and endoscope are inserted into their respective channels. The use of a 0-degree endoscope provides a clear, undeformed view of the operative field. The extremities of the surgical instruments are always visible. This constant visibility reduces the danger of damaging the neural elements. All of the following steps in the procedure are video assisted. Bony Resection Part of the superior lamina and articular process are resected to expose the lateral edge of the dural sheath and nerve root. This bony resection facilitates access to the herniated disk without excessive traction of the root and, above all, avoids damage to another root that might be fused to the root that one expects to find. FIGURE 21–2 Fluoroscopic control with a special device (>) to determine the point of entry and the direction of the approach to the disk. Resection of the Ligamentum Flavum After bone removal, the surgeon can attain the cephalad insertion of the ligamentum flavum, which is then excised with a Kerrison rongeur. Some surgeons may prefer to incise the ligamentum flavum with a scalpel. Dissection of the Nerve Root and Resection of the Disk Herniation Once the nerve root has been well identified, the surgeon isolates it with the nerve retractor at greater magnification. Epidural veins are cauterized, if necessary. The built-in root retractor permits retraction of the nerve root and access to the disk herniation without endangering the neural structures (Fig. 21–3). In certain cases, microdiskectomy is then performed, removing loose fragments of the nucleus. Closure The instrumentation is removed as a single unit. This feature provides video control for hemostasis of the muscles during withdrawal. After the aponeurosis is sutured, the skin is reapproximated with a dermal suture, and a special waterproof bandage is applied. FIGURE 21–3 Use of the nerve-root (N) retractor (R) in a left L4—L5 herniation (*). Cranial is at the left side of the image, and midline is at the top. Postoperative Care The patient is returned to the upright position immediately after the operation. A muscle relaxant is given systematically. Without delay, rehabilitation is begun to mobilize the lumbar spine and relax the paravertebral muscles. The waterproof bandage permits the patient to bathe or take a shower normally. The resumption of previous activities, including sports, is encouraged as soon as possible. No restriction in activity is recommended to the patient. Surgical Technique in Foraminal Herniations After localization of the operative zone with an image intensifier, a small longitudinal incision is made over the spinous process.2 The muscles are detached. The underlying window is found, then one follows the lamina rostrally and laterally to find the lateral, arched edge of the isthmus. This edge is resected more or less according to the placement of the disk herniation in the foramen. The intertransverse ligament and its projections are resected, revealing the root. Dissection then shows the herniated disk (Fig. 21–4). In most cases, only the herniated fragment is excised. No drainage is left in place at closure. FIGURE 21–4 Left foraminal L3–L4 herniation (*). Lateral part of the isthmus (B) and ligamentum (L) have been resected. The nerve root (N) is pushed laterally by the hernia. Cranial is at the left side of the image, and midline is at the top. Surgical Technique in Lumbar Spinal Stenosis A unilateral approach is made, usually on the left side. A part of the lamina, articular process, and ligamentum flavum are resected to expose the dural sac and the nerve-root. A part of the posterior arch of the two vertebrae is then removed, and the posterior part of the dural sac is followed toward its contralateral limit at the upper part of the space. The ligamentum flavum and articular process are then partly resected from upward to downward to expose the contralateral nerve root (Fig. 21–5).3 Complications The following are complications that are possible with the paraspinal endoscopic approach: FIGURE 21–5 Lumbar spinal stenosis. Both left (*) and right (>) L5 nerve roots are exposed. Cranial is at the left side of the image. Advantages of the Endoscopic Technique Limiting the extent of the operative path minimizes muscle lesions and postoperative pain and facilitates rapid resumption of activities. Patients appreciate the cosmetic advantage of the endoscopic procedure (smaller incision). Transporting the surgeon’s field of vision directly into the operative site enhances the delineation of structures, more than compensating for the absence of threedimensional perception. The endoscopic view also facilitates both the hemostasis of deep structures as well as that of the muscles, thus contributing to postoperative comfort. Furthermore, the relatively wide angle of vision enlarges the field of intraoperative exploration. This extension of exploratory limits is particularly helpful in cases of foraminal disk herniation, in which the difference between the view provided by conventional minimally invasive techniques and the present video-assisted technique is striking and widens the indications of this foraminal approach to intracanalar herniations that have migrated rostrally in the axilla of the nerve root. This paramedial endoscopic technique can also be applied in monosegmental stenosis of the lumbar canal, in which case the wide field of view permits decompression of the dural sheath and roots on both sides through a unilateral access. This endoscopic approach to the lumbar spine is a minimally invasive procedure that provides a safe and effective alternative to standard microdiskectomy and spinal stenosis. The technique can be mastered after a short learning curve. Its results are as good as those of microdiskectomy because the surgical technique is the same, but the postoperative comfort is better and patients can resume their previous activities very quickly after surgery. REFERENCES

21

Paraspinal Endoscopic Laminectomy and Diskectomy

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Paraspinal Endoscopic Laminectomy and Diskectomy

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree