Idiopathic Parkinson’s disease

Parkinson’s disease

Genetic forms of Parkinson’s disease

Parkinsonism plus syndromes

Progressive supranuclear palsy

Multiple system atrophy

Cortico-basal ganglionic degeneration

Dementia with lewy Bodies

Hereditary neurodegenerative Parkinsonism

Huntington’s disease

Wilson’ disease

Autosomal dominant spinocerebellar ataxias

Lubag (X-linked dystonia-parkinsonism)

Neuroacanthocytosis

Familial basal ganglia calcification

Fronto-Temporal dementia with parkinsonism

Brain Iron accumulation disorders

Pallidopyramidal syndromes (usually genetic)

Secondary (acquired, symptomatic) Parkinsonism

Infectious: postencephalitic, AIDS, SSPE, Creuzfeldt-Jakob disease

Drugs: dopamine receptor blocking drugs; reserpine, lithium, flunarizine, valproate

Toxins: MPTP, CO, Mn, Hg, cyanide, methanol, ethanol

Vascular: multi-infarct

Trauma: pugilistic encephalopathy

Other: parathyroid abnormalities hypothyroidism, hepatocerebral degeneration, brain tumour, paraneoplastic, normal pressure hydrocephalus

The four main parkinsonism-plus disorders are the synucleinopathies multiple system atrophy (MSA) and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), and the taupoathies progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) and corticobasal degeneration (CBD). These are neurodegenerative disorders that are frequently confused with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease (PD). In fact, about 30 % of pathologically proven parkinsonism plus syndromes are initially misdiagnosed as PD. It is important to concede however that even where strict clinical criteria are retrospectively applied there is incomplete, even poor, clinicopathological correlation in this group of disorders. Whilst PSP, MSA and CBD have clear pathological diagnostic features, the distinction of DLB from Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD) is clinical, and the concept of a spectrum of “Lewy body disease”, rather than splitting the two disorders, is advocated by some authorities.

Accurate differentiation between parkinsonism plus syndromes and PD is important for several reasons, the two most significant being (i) life expectancy is much lower in parkinsonism plus, and (ii) treatments such as levodopa and deep brain stimulation are generally ineffective in parkinsonism plus.

A complete history and neurological examination is critical in establishing a correct diagnosis. General features of an atypical syndrome are symmetric clinical features at onset (with the exception of corticobasal degeneration), and poor L-Dopa response. Features that do occur in Parkinson’s Disease later on in the disease should arouse suspicion if they occur early in the clinical course: early falls, early autonomic features and early cognitive impairment should raise suspicion of a parkinsonism plus syndrome. Some syndromes have specific features that are not seen in IPD, for example square wave jerks or the supranuclear gaze palsy of PSP. Table 10.2 provides a guide to some clinical red flags that should make the examiner consider an alternative diagnosis to PD. Importantly, patients with suspected Parkinson’s disease may declare specific features of a parkinsonism-plus syndrome after their initial presentation, so the physician must keep an open mind and keen observation during follow-up visits.

Table 10.2

‘Red flag’ features in parkinsonism

Clinical feature | Likely cause of parkinsonism |

|---|---|

Young onset Axial rigidity Pill rolling rest tremor Myoclonus Vertical gaze palsy Early falls backwards (1st year) Asymmetric onset Alien limb/apraxia Poor response to levodopa Dysautonomia Early cognitive impairment Laryngeal stridor Palilalia Cerebellar signs Pyramidal signs | Juvenile PD, MSA PSP MSA, CBD PSP PSP PD, CBD CBD PSP, CBD, MSA MSA PSP, CBD MSA PD, PSP MSA MSA |

10.2 Multiple System Atrophy

10.2.1 Clinical Features

Like PSP and CBD, MSA is a progressive, sporadic, adult- onset neurodegenerative disorder. The first cases were described over a hundred years ago by Dejerine and Thomas who referred to olivopontocerebellar atrophy. The term MSA was introduced in 1969 by Graham and Oppenheimer indicating that multiple brain systems are involved (extrapyramidal, pyramidal, cerebellar and autonomic (in any combination)). Patients are clinically classified according to the predominant motor presentation i.e. cerebellar (MSA-C) and parkinsonian (MSA-P) subtype. When autonomic failure predominates or there is primary autonomic failure, MSA is sometimes termed Shy-Drager syndrome, although this term is rarely used nowadays.

Autonomic dysfunction is usually the earliest feature in both MSA-P and MSA-C, with 97 % ultimately developing symptoms. Genitourinary dysfunction is the most frequent initial complaint in women, and early erectile dysfunction is almost invariable in men by 2 years. Orthostatic hypotension is common and is present in at least 68 % of patients. Symptoms associated with orthostatic hypotension include presyncope (lightheadedness, dizziness, blurred vision), fatigue, yawning, “coathanger pain” across the neck and shoulders, and syncope. Akinesia and rigidity are prominent in MSA-P but are usually also evident in the later stages of MSA-C. Cerebellar dysfunction is predominant in MSA-C with gait and limb ataxia the prominent features, but also is seen in a significant proportion of MSA-P cases over time. Notable features supporting a diagnosis of MSA include rapid progression (wheelchair bound <10 years from onset), orofacial dystonia (spontaneous or levodopa-induced), camptocormia (forward trunk flexion resolving in certain postures, typically lying down), Pisa syndrome (lateral trunk flexion), disproportionate antecollis (severe neck flexion or ‘dropped head syndrome’), dysphonia (hoarse/harsh/ high pitched), dysarthria, dysphagia, inspiratory stridor, cold hands and feet, emotional incontinence, pyramidal signs (Babinski and hyper-reflexia), and a jerky myoclonic postural/action tremor of the digits and/or hands (poliminimyoclonus). Only one third of patients with MSA-P respond to levodopa and about 90 % are unresponsive to long-term therapy.

MSA progresses rapidly and most patients develop motor impairment within 1 year of onset. Motor impairment can be caused by cerebellar dysfunction and/or extrapyramidal involvement; corticospinal tract dysfunction can also occur but is not a major symptomatic feature of the condition. At least 50 % of all patients with probable MSA are disabled or wheelchair- bound within 5 years after onset and the median survival is 9.8 years.

Figure 10.1 provides an illustration of the major clinical features of MSA. Table 10.3 shows an international bedside classification system for MSA according to differing levels of diagnostic certainty- possible, probable or definite.

Fig. 10.1

This figure provides an illustration of the major clinical features of Multiple System atrophy (MSA)

Table 10.3

Criteria for MSA

A. Criteria for diagnosis of MSA |

Definite MSA |

Neuropathological findings of widespread and abundant CNS alpha-synuclein-positive glial cytoplasmic inclusions with neurodegenerative changes in striatonigral or olivopontocerebellar structures. |

Probable MSA |

A sporadic progressive, adult (>30 y)- onset disease characterized by |

Autonomic failure involving urinary incontinence or an orthostatic decrease of blood pressure within 3 min of standing by at least 30 mmHg systolic or 15 mmHg diastolic and |

Poorly Levodopa-responsive parkinsonism or |

A cerebellar syndrome/dysfunction |

Possible MSA |

Parkinsonism or |

A cerebellar syndrome/dysfunction and |

At least one feature suggesting autonomic dysfunction (otherwise unexplained urinary urgency, frequency or incomplete bladder emptying, erectile dysfunction or significant orthostatic blood pressure that does not meet the level required in probable MSA) and |

At least one of the additional features shown in Table 10.1b |

B. Additional features of possible MSA |

Possible MSA-P or MSA-C |

Pyramidal signs – Babinski sign with increased tendon reflexes |

Stridor |

Possible MSA-P |

Rapidly progressive parkinsonism |

Poor response to Levodopa |

Postural instability within 3 years of motor onset |

Gait ataxia, cerebellar dysarthria, limb ataxia, or cerebellar oculomotor dysfunction |

Dysphagia within 5 years of motor onset |

Atrophy on MRI of putamen, middle cerebellar peduncle, pons or cerebellum |

Hypometabolism on FDG-PET in putamen, brainstem or cerebellum |

Possible MSA-C |

Parkinsonism |

Atrophy on MRI of putamen, middle cerebellar peduncle, or pons |

Hypometabolism on FDG-PET in putamen |

Presynaptic nigrostriatal dopaminergic denervation on SPECT or PET |

10.2.2 Epidemiology

There is an estimated incidence of 1.2–4.1 cases per 100,000 population per year, with an estimated prevalence of 0.9–8.4 cases per 100,000. However, as with the other atypical parkinsonian disorders, ascertainment (due to frequent misdiagnosis) poses a significant problem, so this is probably under-estimated. About 30 % of patients with late-onset sporadic cerebellar ataxia have MSA. MSA has been reported in Caucasian, African and Asian populations. MSA-P predominates in western countries (68–82 %) whilst in Eastern countries, MSA-C is more common, constituting 67–83 % of patients. Most studies indicate a slight male predominance and the mean patient age at onset is 54.3 years with a range of 33–78 years.

10.2.3 Neuropathology and Molecular Pathology

The neuropathological substrate of MSA-C is olivopontocerebellar degeneration (inferior olivary nucleus, pons, and cerebellum) whilst that of MSA-P is striatonigral degeneration (substantia nigra, putamen, caudate nucleus and globus pallidus). Even though they can be clinically very different, MSA-C and MSA-P share oligodendroglial cytoplasmic inclusions (GCIs) as a unifying pathological feature. Both subtypes display neural loss and gliosis in their respective regional brain distributions and both are frequently accompanied by neurodegeneration of the autonomic nervous system; the severe clinical correlate of this is Shy-Drager syndrome.

Approximately 30 % of Caucasian patients have principally striatonigral pathology, 20 % olivopontocerebellar pathology and the remaining 50 % have equal amounts of both. Pathological degeneration of the putamen appears to correlate with the poor levodopa response in MSA.

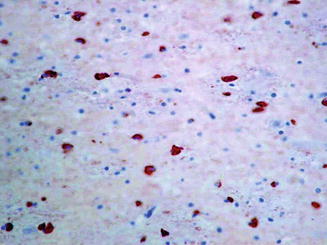

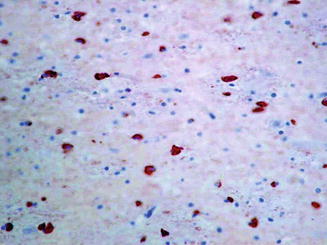

Oligodendroglial cytoplasmic inclusions, which define MSA neuropathology, are formed by fibrillized (aggregated, insoluble) alpha-synuclein protein (see Fig. 10.2). Genome-wide screening in MSA has identified an association between certain SNPs in the alpha synuclein gene and MSA risk, and transgenic mice over-expressing alpha synuclein under the control of specific oligodendroglial promoters develop GCI-like inclusions. These findings confirm MSA as a ‘synucleinopathy’ similar to PD and dementia with Lewy Bodies (see Table 10.4) but it appears that oligodendrogliopathy precedes neuronal degeneration in MSA.

Fig. 10.2

Alpha-synuclein immunostaining to show cytoplasmic immunopositivity in glial cells (glial cytoplasmic inclusions (GCI)) within subcortical white matter (magnified ×40 before photo enlargement). The authors acknowledge Professor Michael Farrell for this image

Table 10.4

Selected synucleinopathies and tauopathies

Synucleinopathies | Tauopathies |

|---|---|

Progressive supranuclear palsy | Parkinson’s disease |

Fronto-temporal dementia | Multiple system atrophy |

Corticobasal disease | Lewy body dementia |

Pick’s disease | |

Argyrophilic brain disease | |

PD – dementia complex – Guam | |

Post-encephalitic PD |

Aberrant myelin basic protein may also be pathogenic in MSA raising the possibility that this is a primary disorder of myelin-producing oligodendroglial cells. However, no studies to date have linked these two plausible hypotheses.

10.3 Laboratory Tests

Investigations of autonomic function include the table-tilt test or active stand to measure orthostatic blood pressure and sphincter electromyography. The latter detects denervation in the external urethral sphincter secondary to degeneration of Onuf’s nucleus in the spinal cord. Cardiac scintigraphy demonstrates reduced sympathetic MIBG uptake in the heart in PD but not MSA. Clinically, this test is more commonly used in Eastern countries than in the West. Video-polysomnography can be helpful in identifying the sleep disturbances associated with MSA (sleep apnoea, nocturnal stridor, REM sleep behaviour disorder (REMBD)).

10.3.1 Radiological Findings

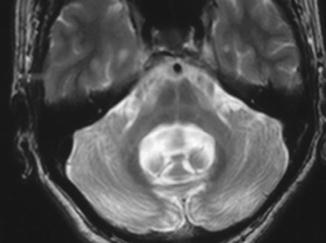

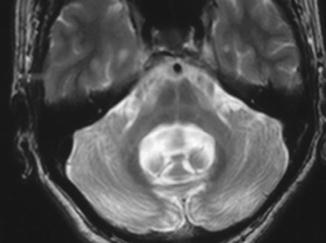

MRI findings in MSA-P often show decreased signal intensity in the posterolateral putamen bilaterally on T2 weighted images. In addition to putaminal hypointensity on T2, a characteristic finding in MSA is the slit-hyperintensity in the lateral margin of the putamen, related to putaminal atrophy. The MRI abnormalities of MSA-C consist of atrophy of the pons, middle cerebellar peduncles, and cerebellum. A characteristic “hot cross bun sign” is described, produced by selective loss of myelinated transverse pontocerebellar fibers and neurons in the pontine raphe with relative preservation of the pontine tegmentum and corticospinal tracts (Fig. 10.3).

Fig. 10.3

Axial T2-MRI showing a cross of signal hyperintensity within the body of the pons originally described by Quinn as a hot cross bun

10.3.2 Management

There is no effective disease-modifying therapy and a multidisciplinary approach is recommended, with supportive care from the allied health professional team. A number of symptomatic therapies are can be deployed to good effect. Orthostatic hypotension is often the earliest and most debilitating symptom. Along with simple explanation and advice regarding care when standing, the addition of liberal salt, increasing fluid intake, head elevation when sleeping and elastic stockings may improve standing blood pressures. Several drugs are used for the management of orthostatic hypotension including fludrocortisone (mineralocorticoid), midodrine (alpha1-adrenoreceptor agonist), droxidopa (synthetic precursor of norepinephrine), and less commonly NSAIDs (possible inhibition of vasodilator prostaglandins) and pyridostigmine (putative vasoconstrictive effect). Therapy can be limited by supine hypertension which affects up to 60 % of patients. Bladder symptoms including urinary retention and incontinence are relatively common and troublesome problems. Formal urodynamics with measurement of post micturition volumes are important, particularly with co-existing prostatism. Overactive bladder symptoms may improve with anti-muscarinics such as oxybutynin or tolterodine while some patients require intermittent self catherisation. Medication may also be considered for constipation and erectile dysfunction, although silenafil and other phosphodiesterase inhibitors should be used with caution as they frequently exacerbate orthostatic hypotension.

It is worth considering Levodopa replacement but the results are usually poor, with only a minority of patients witnessing benefit, which is typically short-lived. A trial of L-Dopa is considered negative if a dose of 1,000 mg per day is reached with no clinical benefit. Caution must be exercised given the risk of exacerbating non-motor features, in particular orthostatic hypotension.

RBD can be treated symptomatically with clonazepam or melatonin; sleep apnoea may be ameliorated by continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). Concomitant depression (estimated to affect at least 40 % of patients) can be treated effectively with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or SNRIs.

10.4 Progressive Supranuclear Palsy: Clinical Features

Steele, Richardson and Olszewski presented the first clinicopathological descriptions of PSP in 1963 and 1965. Unsteadiness of gait, with falls within the first year, frequently backwards, represents the presenting feature in more than 60 % of cases. Bradykinesia and rigidity may be associated, often resulting in a misdiagnosis of PD, but these features have an axial predominance in PSP, unlike PD which tends to have asymmetric lateralised features in the early stages. In a minority of cases gaze difficulties, dysarthria, dysphagia or cognitive impairment may be the prominent early symptoms (see Fig. 10.4). The illness progresses to an immobile state over less than 10 years in the majority of cases. Recent years have witnessed a considerable expansion in the volume of clinic-pathological series describing PSP and there is now widespread recognition that there can be considerable phenotypic heterogeneity, particularly in the early years of the disease. This has given rise to the proposed clinical subdivision of PSP into a number of sub-entities, and there is some pathological data to corroborate this. Such clinical subtypes include the classic phenotype as described by Steele et al. (PSP-RS); PSP-parkinsonism (PSP-P) which can mimic IPD with asymmetric features, tremor and partial levodopa responsivity for a number of years, as well as a corticobasal syndrome (PSP-CBS), a primary progressive aphasia phenotype (PSP-PNFA), and rarely, gait initiation failure and freezing of gait, speech or writing in the absence of other parkinsonian signs (PSP-PAGF). Ultimately, however, the disease evolves in the vast majority of patients into the classical picture of axial rigidity, postural instability, oculomotor palsies, bulbar dysfunction and cognitive (particularly frontal lobe) impairment.

Fig. 10.4

This figure provides an illustration of the major clinical features of Progressive Supranuclear Palsy

In contrast to the short and shuffling gait, stooped posture, narrow base, and flexed knees typically seen in PD, PSP patients tend to be erect with a stiff and broad-based gait, often with poor safety awareness and impulsivity (“motor recklessness”). They tend to pivot when turning, which further compromises balance. Although the PSP gait can appear ataxic, cerebellar signs are not a feature.

Oculomotor abnormalities are common in PSP. Symptomatic eye movement difficulty is typically present within 4 years after the onset. Prior to this, most patients have slowing of vertical saccades, saccadic pursuit, breakdown of opticokinetic nystagmus in the vertical plane, poor convergence and square-wave jerks (SWJs). The latter occurs in nearly all patients with PSP and rarely in PD. Vertical supranuclear ophthalmoparesis is a prominent feature of PSP. The patient loses range of vertical gaze, with downgaze usually worse than upgaze, and will describe difficulty walking down stairs. This voluntary gaze restriction is supranuclear; it therefore can be overcome by using the vestibulo-ocular reflex (“Doll’s eye” manoeuvre) achieved by passive flexion/extension of the neck. Involuntary orbicularis oculi contractions producing blepharospasm and ‘apraxia’ of eyelid opening and eyelid closure affect up to one third of PSP patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree