Personality and personality disorder

The historical development of ideas about abnormal personality

The classification of abnormal personalities

Descriptions and diagnostic criteria

Rates of personality disorder in the clinic and the general population

The course of personality disorder

The management of personality disorders

The management of specific personality disorders

Personality

The term personality refers to those enduring qualities of an individual that are shown in their ways of behaving in a wide variety of circumstances, and which we use to distinguish between people. Personality therefore differs from mental disorder in that the behaviours which define it have been present throughout adult life, whereas the behaviours that define mental disorder differ from the person’s previous behaviour. When we say that a mentally ill person is ‘not their normal self’, we are drawing on our understanding of their personality and usual behaviour. The distinction is easy to make when behaviour changes markedly over a short period of time (as in a manic disorder), but can be difficult when the changes occur very gradually (as in some cases of schizophrenia).

The importance of personality

Gaining an understanding of and familiarity with a patient’s personality is important in psychiatry. Different personalities predispose to some psychiatric disorders, and they may account for unusual features or colour the presentation of a psychiatric disorder (‘pathoplastic’ factors). They may also explain how a patient approaches treatment, and dictate different strategies for establishing and maintaining a successful therapeutic relationship.

Personality as predisposition

Personality can predispose to psychiatric disorder by modifying an individual’s response to stressful events. For example, adverse circumstances are more likely to induce an anxiety disorder in a person who has always worried about minor problems.

Personality as a pathoplastic factor

Personality can contribute to unusual features of a disorder, particularly when personality traits become exaggerated with illness. For example, rumination and inhibition may be the presentation of depression in an individual with an obsessional personality. The underlying diagnosis can be obscured if the psychiatrist has not made an accurate assessment of personality.

Personality in relation to treatment

Personality is an important determinant of a person’s approach to treatment. For example, people with obsessional traits may become frustrated and resistant if treatment does not follow their expectations, and anxiety-prone people may discontinue medication prematurely because of concerns about minimal side-effects. Some people with a severe disorder of personality, particularly so-called Cluster B disorders (antisocial, borderline, impulsive, histrionic, and narcissistic personality disorders; see below) have often been effectively excluded from services because of the difficult relationships they form with clinicians (see Lewis and Appleby, 1988). This is a significant problem, as there is strong evidence that personality disorder is common in clinical populations, and that people with personality disorders have an increased risk for a range of mental illnesses (Moran, 2002). There is now a concerted move to remedy this (National Institute for Mental Health in England, 2003), which will be addressed later in this chapter and in Chapter 20.

Patients are often aware of their personalities—they know if they are ‘emotional’ or ‘conscientious’ or ‘anxious.’ Acknowledging this diplomatically (making sure to note the positive aspects as well as the negative ones) and discussing how it may interact with their treatment (and with their life generally) can be an effective tool in maintaining treatment.

Personality types

A first step in understanding personality is to identify some basic types. Clinicians have generally derived these from a mixture of clinical and common-sense collective experience with several generally recognizable categories, such as a sociable and outgoing type, a solitary and self-conscious type, and an anxious and timid type. Psychologists have adopted a more rigorous scientific approach using personality tests to measure aspects of personality (‘traits’) such as anxiety, energy, flexibility, hostility, impulsiveness, moodiness, orderliness, and self-reliance. These are then subject to statistical methods to discover which of them cluster into ‘factors.’

Although these statistical procedures appear very scientific, it is important to remember that their results are determined by the original hypotheses of the investigators (which traits they considered to be important and included in their analyses, and the order in which they included them, etc.). Like diagnoses, these are essentially working hypotheses, which are continuously evolving and should not be treated with too much reverence—their value lies in their utility.

Different investigators have derived different personality factors from such traits. Cattell (1963) identified five factors, whereas Eysenck (1970a) originally proposed only two ‘dimensions’ (high-level factors), which he labelled extraversion–introversion and neuroticism. Subsequently he added a third dimension, ‘psychoticism ‘(Eysenck and Eysenck, 1976), but his use of the term is rather misleading, denoting coldness, aggressivity, cruelty, and antisocial behaviour.

A five-factor formulation for personality has persisted, although the terms used for the factors have varied. They can be identified as openness to experience (or novelty seeking), conscientiousness, extraversion–introversion, agreeableness (or affiliation), and neuroticism. Widiger and Costa (1994) proposed that each of these five factors is composed of six traits, and developed assessment inventories based on self-report and report from informants (Costa and McCrae, 1992), as well as a semi-structured interview (Trull and Widiger, 1997).

Cloninger (1986) and Cloninger et al. (1993) developed an alternative scheme with three ‘basic behavioural dispositions’ expressed as four basic temperaments (a seven-factor model). The behavioural dispositions are behavioural activation, behavioural inhibition, and behavioural maintenance. Cloninger considered behavioural activation to be associated with the basic temperament of novelty seeking, behavioural inhibition with harm avoidance, and behavioural maintenance with reward dependence. The fourth basic temperament is persistence. Cloninger’s scheme also includes three character traits, namely self-directedness, cooperativeness, and transcendence. The various types of personality and personality disorder are constructed from these four basic temperaments and three character traits. Cloninger’s scheme is noteworthy for its inclusion of both inherited differences in brain function and the effects of experience.

These factor schemes of personality have survived despite sustained criticism that they are largely dependent on what was included in the original factor analyses. Zuckerman (2005) has also criticized these theories because they assume an alignment between personality traits and brain systems (Zuckerman, 2005). In recent years there has been some refinement, with greater emphasis on cognitive factors. Matthews has proposed a cognitive–adaptive theory (Matthews and Dorn, 1995; Penke and Denissen, 2007), and Mischel has emphasized the dynamic nature of personality in his cognitive–affective system (Mischel et al., 2004). Current texts on personality theory (for example, Matthews et al., 2003) are weighty tomes, and those interested in deepening their understanding might be best advised to start by consulting a clinical psychology colleague.

Despite these scientific approaches, clinicians continue to use everyday words to describe the positive and negative features of normal personality. Positive attributes include ‘outgoing’, ‘self-confident’, ‘stable’, and ‘adaptable.’ Negative attributes include ‘sensitive’, ‘jealous’, ‘irritable’, ‘impulsive’, ‘self-centred’, ‘rigid’, and ‘aggressive.’

The origins of personality

The biological basis of personality types

Genetic influences

Everyday observation suggests that children often resemble their parents in personality. Such similarities could be either inherited or acquired through social learning. Three kinds of scientific study have been used to study the inheritance of personality.

Studies of body shape and personality. Different personalities have been linked to body shape (‘beware of Brutus, he has a lean and hungry look’). If this were true, the link could be genetic. Kretschmer (1936) described three types of body build—pyknic (stocky and rounded), athletic (muscular), and asthenic (lean and narrow). He suggested that the pyknic body build was linked to the cyclothymic personality type (sociable with variable moods), whereas the asthenic build was related to the ‘schizotypal’ personality type (cold, aloof, and self-sufficient). Kretschmer’s ideas were based on subjective judgements, and were influenced by experience of the ‘associated’ psychotic disorders (manic-depressive disorder and schizophrenia). Sheldon used quantitative methods to assess physique and more objective ratings of personality, and failed to support the link (Sheldon et al., 1940).

Studies of twins. More direct evidence has been obtained from personality tests of identical twins reared together or reared apart. These suggest that the heritability for traits of extraversion and neuroticism is 35–50% (McGuffin and Thapar, 1992). The heritability of other traits is broadly similar.

Linkage studies. Molecular genetic studies have sought linkages for measures of novelty seeking and of neuroticism. Several quantitative trait loci have been identified that influence variations in neuroticism (Fullerton et al., 2003). Linkage between harm avoidance and a region on 8p21 has been reported in one study (Zohar et al., 2003). Such studies are difficult and require confirmation, but they may clarify the biological basis of some aspects of personality.

Childhood temperament and adult personality

Young infants differ in patterns of sleeping and waking, approach or withdrawal from new situations, intensity of emotional responses, and span of attention. These differences, which are described in more detail in Chapter 22, could form the basis for personality development. Although they do persist into later childhood, they have not been shown to be related to adult personality (Berger, 1985).

Childhood experience and personality development

Everyday experience suggests that childhood experience shapes personality (society is built on this premise), but it is not easy to demonstrate it. Experiences that seem relevant are difficult to quantify or even to record reliably, and it is extremely difficult and expensive to conduct prospective studies that span the time period from childhood events to adult personality. Retrospective studies are easier to arrange, but recall of childhood experiences is unreliable. Although scientifically collected information is sparse (see the section on aetiology of personality disorder below), the psychodynamic theories of Freud retain considerable influence.

The Freudian theory of personality development emphasizes events during the first five years of life. Freud proposed that crucial stages of libido development (which he rather unhelpfully referred to as ‘oral’, ‘anal’, and ‘genital’) must be accomplished successfully for healthy personality development. Failure or fixation at particular stages explained certain features of adult personality—for example, difficulties at the anal stage would lead to obsessional personality traits. Some personality growth was possible later, through identification with people other than the parents, but this influence was less strong. Freud’s explanation is excessively comprehensive and flexible. It can be made to explain almost all personality variation in terms of infantile experience, but its very flexibility makes it impossible to test scientifically. However, it retains enormous intuitive appeal and is widely used both within and outside of psychiatry.

Jung’s theory of personality development also recognizes the importance of psychic events in early life, but unlike Freud, Jung considered personality development to be a lifelong process. He considered individuation to be the aim of personal development, and his theories are particularly valued in relation to the disorders of later life. He proposed a structured theory of personality and introduced the terms ‘introvert’ and ‘extrovert.’

Adler and the neo-Freudians rejected Freud’s exclusive focus on libido development. Adler emphasized a struggle for mastery (overcoming the ‘inferiority complex’) as the driving force in personality development. The ‘neo-Freudians’ (Fromm, Horney, and Sullivan) increasingly emphasized social and peer-group factors in personality development.

Erik Erikson proposed an essentially similar process to that of Freud, although his nomenclature is less offputting, and is framed in terms of the individual developmental challenges. The oral stage is trust versus mistrust when feelings of security develop. The anal stage is autonomy versus doubt, when the child learns self-control, social rules, and self-confidence. The genital stage is initiative versus guilt, when children develop their image of themselves as people, leading to confidence and initiative. Erikson extended Freud’s idea of a latency period into adolescence, and called this last stage the period of industry versus inferiority. Erikson’s scheme recognizes the importance of adolescence for personality development, whereas Freud largely ignored it.

The assessment of personality

The assessment of personality is discussed in Chapter 3, but two points need to be emphasized. The first is that the assessment of personality used in everyday life cannot be applied reliably in clinical practice. Normally we assume that current behaviour reflects the person’s habitual ways of behaving (their personality), and in general this assumption is correct. This is not the case when we assess patients, because their current behaviour reflects the effects of their illness as well as their personality. A patient’s personality can only be judged confidently from reliable accounts of past behaviour, which have been obtained wherever possible from informants as well as from the patient.

Secondly, the assessment instruments developed for personality mentioned earlier (see p. 130), although more reliable in healthy individuals, can be misleading in the presence of mental disorder. In addition, they rarely measure the traits that are most relevant to clinical practice. Personality tests, although useful in research, are seldom used in clinical practice. For a review of personality assessment methods, see Westen (1997) and Clark and Harrison (2001).

The importance of personality assessment

The assessment of personality is important when making decisions about aetiology, diagnosis, and treatment. In aetiology, knowledge of personality helps to explain why certain events are stressful to that patient. In diagnosis, an understanding of personality may explain the presence of unusual features in a disorder which might otherwise cause uncertainty. In treatment, an assessment of personality helps to explain the patient’s reaction to their illness and its treatment, and aids the establishment of an effective therapeutic relationship. Personality assessment should be an integral part of every formulation, and not just reserved for those where a personality disorder is suspected.

It is best to record a series of descriptive terms chosen from the features of accepted personality disorders, because the more theoretical personality factors are too general to help the clinician. Examples would be ‘sensitive’, ‘lacking in self-confidence’, and ‘prone to worry.’ Such descriptions help to construct a picture of the unique features of each patient, which is a fundamental element of good clinical practice.

Personality disorder

The concept of abnormal personality

Some personalities are obviously abnormal—for example, paranoid personalities characterized by extreme suspiciousness, sensitivity, and mistrust. However, it is impossible to draw a sharp dividing line between normal and abnormal personalities. Abnormal personalities are in practice recognized because of the pattern of their characteristics, but our current classificatory processes in psychiatry demand that we identify criteria for inclusion. However, precisely which criteria should be used to make this distinction remains controversial. Two types of criteria have been suggested, namely statistical and social.

According to the statistical criterion, abnormal personalities are quantitative variations from the normal, and the dividing line is decided by a cut-off score on an appropriate measure. This approach is attractive, as it parallels that used successfully when defining abnormalities of intelligence, it appears non-judgemental, and it has obvious value in research. However, its usefulness in clinical practice is uncertain.

According to the social criterion, abnormal personalities are those that cause the individual to suffer, or to cause suffering to other people. For example, an abnormally sensitive and gloomy personality causes suffering for the individual who has it, and an emotionally cold and aggres sive personality causes suffering for others. These criteria are subjective and lack the precision of the first approach, but they serve the needs of clinical practice better and they have been widely adopted.

It is not surprising that it is difficult to frame a satisfactory definition of abnormal personality. ICD-9 describes personality disorders as follows:

Severe disturbances in the personality and behavioural tendencies of the individual, not directly resulting from disease, damage or other insult to the brain, or from another psychiatric disorder. They usually involve several areas of the personality and are nearly always associated with considerable personal distress and social disruption. They are usually manifest since childhood or adolescence and continue throughout adulthood.

ICD-10 emphasizes enduring patterns of behaviour, but the ICD-9 definition is more concise, and still valuable.

The ‘personal distress’ referred to in ICD-9 may sometimes only become apparent late in life (e.g. when a longstanding supportive relationship is lost). There are usually, although not always, significant problems in occupational and social performance.

It is important to recognize that people with abnormal personalities generally also have favourable traits, which the clinician should always assess. For example, those with obsessional traits are often dependable and trustworthy. Management plans that play to an individual’s strengths are more likely to be helpful for them.

Personality change

In some circumstances during adult life there may be a profound and enduring change in personality that is distinct from the temporary changes that may accompany stressful events or illness. This lasting change may result from:

• injury to or organic disease of the brain

• severe mental disorder, especially schizophrenia

• exceptionally severe stressful experiences (e.g. those experienced by hostages or by prisoners undergoing torture).

ICD-10 contains categories for each type of change. Change in personality due to organic disease of the brain is classified with the organic mental disorders in section F00, and includes the changes that occur following encephalitis and head injury. In DSM-IV this condition is diagnosed as personality change due to a general medical condition.

In ICD-10 the other two forms of personality change listed above are classified in section F60, disorders of adult personality and behaviour. To diagnose enduring personality change after psychiatric illness, the change of personality must have lasted for at least 2 years, be clearly related to the experience of the illness, and not have been present before it. Enduring personality change after a catastrophic experience must also have lasted for at least 2 years and have followed a stressful experience that was extreme (e.g. prolonged kidnapping, a terrorist attack, or torture). Victims are commonly hostile, irritable, distrustful, socially withdrawn, and on edge. The condition may follow post-traumatic stress disorder, but is distinct from it.

The historical development of ideas about abnormal personality

The concept of abnormal personality can be traced back to the beginning of psychiatry as a discipline at the turn of the nineteenth century, when the French psychiatrist Philippe Pinel described manie sans délire. By this he meant patients who were prone to outbursts of rage and violence, but who were not deluded. Delusions were then regarded as the hallmark of mental illness, and délire is the French term for delusion. J. C. Prichard, senior physician to the Bristol Infirmary, wrote about abnormal personality in 1835 in A Treatise on Insanity and Other Disorders of the Mind. After referring to Pinel’s manie sans délire, he suggested a new term, moral insanity, which he defined as a:

morbid perversion of the natural feelings, affections, inclinations, temper, habits, moral dispositions and natural impulses, without any remarkable disorder or defect of the intellect or knowing or reasoning faculties, and in particular without any insane delusion or hallucination.

(Prichard, 1835, p. 6)

Prichard’s moral insanity included conditions which we would now diagnose as personality disorder. It is important to remember that the term ‘moral’ had a wider meaning at this time, much akin to our term ‘social.’ The ‘moral treatment’ that was introduced by Pinel and developed by the Tuke family in the York Retreat in the 1790s was focused not on ethical judgements but on socialization. Prichard did not confine the term to people who had always behaved in these ways:

When, however, such phenomena are observed in connection with a wayward and intractable temper, with a decay of social affections, an aversion to the nearest relatives and friends formerly beloved—in short, with a change in the moral character of the individual—the case becomes tolerably well marked.

Later, the term ‘moral insanity’ was used by Henry Maudsley more as we would understand an antisocial personality disorder, to describe someone as having:

no capacity for true moral feeling—all his impulses and desires, to which he yields without check, are egoistic, his conduct appears to be governed by immoral motives, which are cherished and obeyed without any evident desire to resist them.

(Maudsley, 1885, p. 171)

Maudsley expressed a growing dissatisfaction with the term, which he referred to as ‘a form of mental alienation which has so much the look of vice or crime that many people regard it is an unfounded medical invention’ (Maudsley, 1885, p. 170).

Julius Koch introduced the term ‘psychopathic inferiority’ (Koch, 1891) for this group with marked abnormalities of behaviour in the absence of mental illness or intellectual impairment. Inferiority was subsequently replaced by personality. Emil Kraepelin was at first uncertain how to classify these people, and it was not until the eighth edition of his textbook was published that he finally adopted the term ‘psychopathic personality.’ He devoted a whole chapter to it, including not only the antisocial type but also six others (excitable, unstable, quarrelsome, and eccentric, together with liars and swindlers).

Kurt Schneider broadened the concept of psychopathic personality. Whereas Kraepelin’s seven types of psychopathic personality consisted of people who caused inconvenience, annoyance, or suffering to others, Schneider included people with markedly depressive or insecure characters, using the term ‘psychopathic’ to cover the whole range of abnormal personality, not just antisocial personality. The term came to have two meanings—a wider meaning of abnormal personality of all kinds, and a narrower meaning of antisocial personality—which has led to subsequent confusion.

In the 1959 Mental Health Act for England and Wales, psychopathic disorder was interpreted narrowly, and in the 1983 Act it was defined as:

a persistent disorder or disability of mind (whether or not including significant impairment of intelligence) which results in abnormally aggressive or seriously irresponsible conduct on the part of the person concerned.

This narrow concept, which emphasized aggressive or irresponsible behaviour, made its inclusion in the Act controversial. Consequently, the proviso of ‘treatability’ as a condition of detention was added exclusively to it, out of all the mental disorders. This distinction was abandoned in the 2007 amendment to the Mental Health Act (see Chapter 4) because it was perceived to present a barrier to effective treatment.

A recent development is the administrative category of dangerous and severe personality disorder (DSPD). This refers mainly to men with antisocial personality disorder and a history of serious violent or sexual offending. Its definition is based on three criteria:

1. a history of serious violent offending and the risk of at least 50% that a similar offence is likely to occur again

2. a severe personality disorder defined either clinically or using the Hare Psychopathy Checklist (Hare, 1991)

3. a demonstrable link between the offending and the personality disorder (Home Office, 1999).

This category (and four pilot units to treat 300 such men) was introduced in order to reduce risk. However, the recent change in the law to allow indeterminate detention of prisoners who still pose a serious risk may render the initiative redundant.

Because the term ‘psychopathic personality’ is ambiguous, the preferred terms are personality disorder and antisocial personality disorder to denote the wide and narrow senses, respectively.

The classification of abnormal personalities

General issues

The use of categories

Personality traits are continuously distributed, but the classification of psychiatric disorders uses categories and require definitions and boundaries. However, the criterion for inclusion (distress to the person or to others) is very imprecise, so cases that fall just short of it (subthreshold cases) are frequent. These sub-threshold cases often present clinical problems that are similar to those of definite cases.

Comorbidity

It is not only the boundary between normal and abnormal personality that is imprecise and arbitrary; the boundaries between the different types of personality are also ill defined. This leads to an important divergence of practice between clinical psychiatrists and researchers and some psychologists. Many patients have features contained in the criteria for more than one personality disorder (Fyer et al., 1988). Structured instruments for measuring personality disorder, such as the International Personality Disorder Examination (Loranger et al., 1997), are often used by researchers and psychologists. They permit more than one personality diagnosis to be made in a single patient, and the term ‘comorbidity’ is used. From a clinical perspective it seems more likely that the patient has a single personality disorder that has features which overlap two of the arbitrary sets of criteria used in the current systems of diagnosis. We would usually diagnose the single personality disorder that best fits the mixed picture and is most useful in understanding and helping the patient in front of us. The concept of comorbidity is used when a patient has both a mental illness and a personality disorder (or more often a mental illness and substance abuse), but makes little clinical sense for personality disorder alone.

Conditions related to personality disorder and classified elsewhere

Cyclothymia and schizotypal disorder were previously classified as personality disorders. In ICD-10 both of these conditions have been removed from the personality disorders and classified instead with the mental disorders (cyclothymia with affective disorders, and schizotypal disorder with schizophrenia). This reflects the fact that these two conditions may begin in adult life, and in the case of schizotypal disorder, evidence from family studies that links it genetically to schizophrenia (see p. 145). In DSM-IV, cyclothymic disorder is classified with mood disorders but schizotypal disorder is retained as a personality disorder. In both classifications, multiple personality disorder is classified with dissociative disorders.

Classification of personality disorders in ICD-10 and DSM-IV

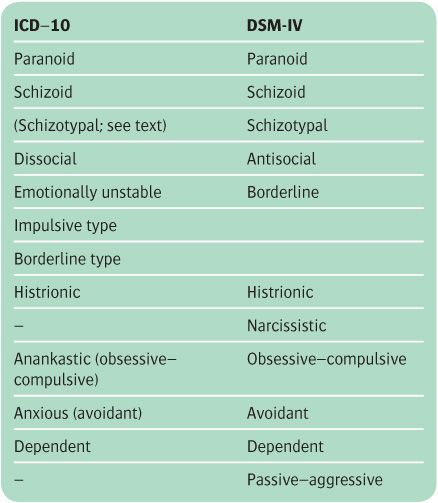

In Table 7.1 the classification of personality disorders in ICD-10 is compared with that in DSM-IV. The two schemes are broadly similar, but there are some differences.

Table 7.1 Classification of personality disorders

The use of Axis II

In DSM-IV, personality disorders are classified on a different ‘axis’ (Axis II) from mental disorders (which are classified on Axis I). This emphasizes the different nature of the two types of diagnosis, and encourages an assessment for personality disorder in every case. This convention is not adopted in ICD-10. The personality should still be assessed, and if no personality disorder is present this should be recorded in the formulation.

Grouping into clusters

In DSM-IV, but not in ICD-10, personality disorders are grouped into three ‘clusters’:

1. Cluster A: paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal

2. Cluster B: antisocial, borderline, histrionic, and narcissistic

3. Cluster C: avoidant, dependent, and obsessive–compulsive.

This convention is adopted later in this chapter.

Different names for the same personality disorder

The individual names for personality disorders differ some what between the two classifications. This reflects the real uncertainty about their boundaries and also an attempt through renaming to de-stigmatize some disorders. In ICD-10 the term ‘dissocial’ is used, whereas in DSM-IV the term ‘antisocial’ (the term used in this book) is used. In ICD-10, the term ‘anankastic’ is used, whereas ‘obsessive–compulsive’ is used in DSM-IV. In ICD-10, the term ‘anxious’ is used, whereas ‘avoidant’ is used in DSM-IV.

Conditions that are present in one classification but not the other

Emotionally unstable impulsive personality disorder and enduring personality change not attributable to brain damage or disease are found in ICD-10 but not in DSM-IV. Narcissistic personality disorder and passive–aggressive personality disorder are included in DSM-IV but not in ICD-10 (passive–aggressive personality disorder is listed as a category for further study). As noted above, schizotypal personality disorder is classified with schizophrenia in ICD-10 (and named schizotypal disorder), whereas in DSM-IV it is classified as a personality disorder.

Descriptions and diagnostic criteria

This section contains an account of the abnormal personalities listed in ICD-10 and DSM-IV (see Table 7.1). The criteria for diagnosis are lengthy, and differ somewhat in wording and emphasis in the two systems. The main common features from the two sets of definitions are given, simplified or paraphrased where appropriate to give a more general description.

All personality disorder diagnoses must meet the basic criteria for personality disorder summarized from the ICD-10 criteria for research as follows:

• The characteristic and enduring patterns of behaviour differ markedly from the cultural norm and in more than one of the following areas: cognition, affectivity, control of impulses and gratification, and ways of relating to others.

• The behaviour is inflexible, and maladaptive or dysfunctional in a broad range of situations.

• Personal distress is caused to others and/or to self.

• The presentation is stable and long-lasting, usually beginning by late childhood or adolescence.

• The behaviour is not caused by another mental disorder, or by brain injury, disease, or dysfunction.

There are several diagnostic instruments for personality disorder (see Box 7.1), but they are mainly of value in research.

Cluster A personality disorders

Paranoid personality disorder

Such people are suspicious and sensitive (see Table 7.2). They have a marked sense of self-importance, but easily feel shame and humiliation. They are suspicious and constantly on the lookout for attempts by others to deceive or exploit them, which makes them difficult for other people to get on with. They are usually mistrustful and often jealous. They have difficulty making friends and avoid involvement in groups. They may appear secretive, even devious, and self-sufficient to a fault. They take offence easily and see rebuffs where none was intended.

They are sensitive to rebuff, prickly, and can be argumentative, often reading demeaning or threatening meanings into innocent remarks. Ernst Kretschmer described how their suspicious ideas can be so intense that they are mistaken for persecutory delusions. These sensitive ideas of reference are considered further in Chapter 12. Paranoid individuals can be resentful and bear grudges, with a strong sense of their rights. They may engage in litigation, often persisting with this against all advice.

Paranoid personalities sometimes have a sense of self-importance, and may consider that others have prevented them from fulfilling their potential.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree