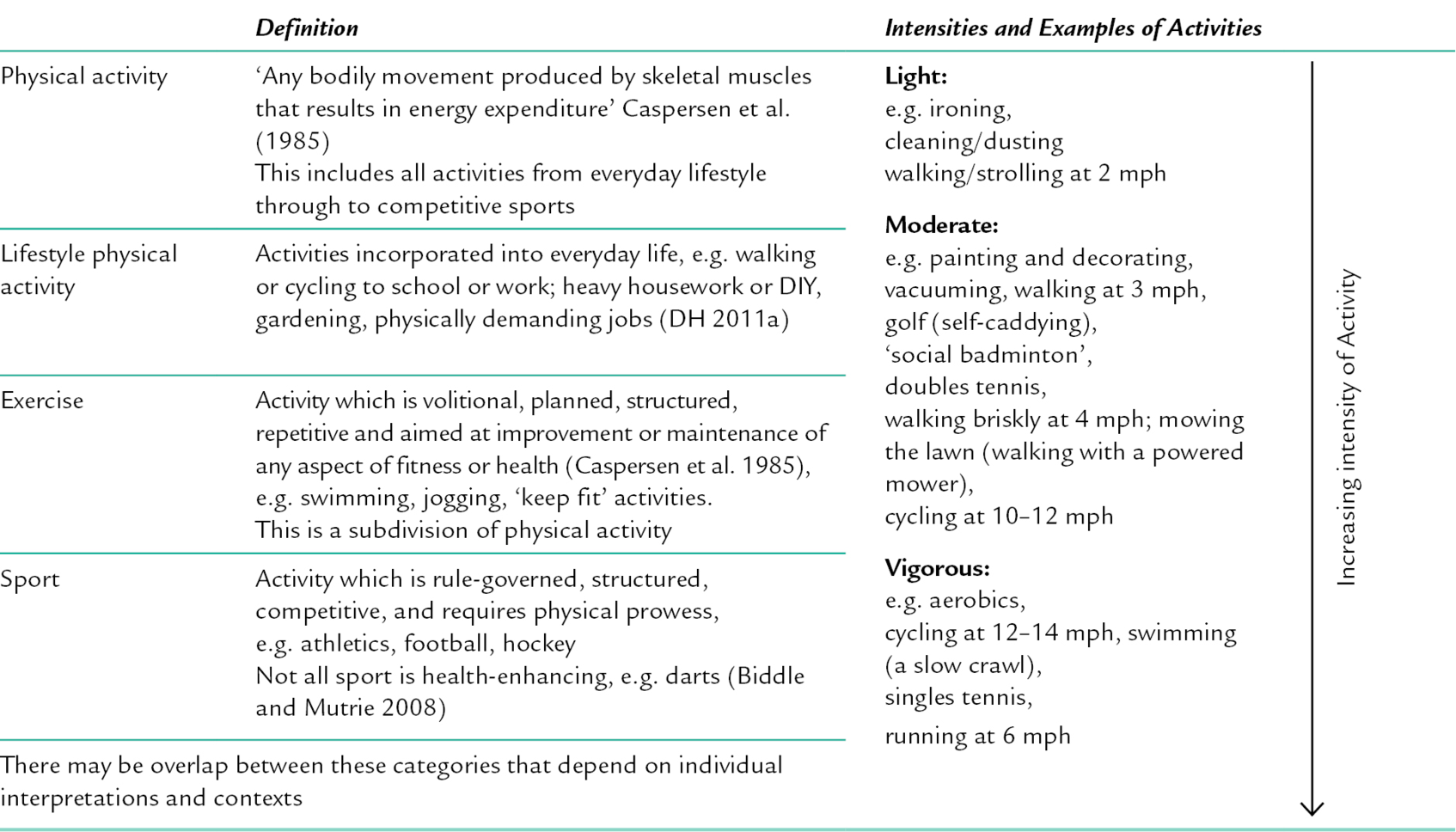

14 CHAPTER CONTENTS Physical Health and Mental Health Promotion PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND MENTAL HEALTH The Nature of Physical Activity The Health Benefits of Physical Activity Cognitive Problems and Dementia Using and Generating Research-Based Evidence PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND MENTAL WELLBEING ADOPTING AND MAINTAINING PHYSICALLY ACTIVE BEHAVIOURS ENABLING PHYSICAL ACTIVITY: DIFFERENTIATING BETWEEN PARTICIPATION AND ENGAGEMENT A Lifestyle Approach to Participation in Physical Activity An Occupational Approach to Engagement in Physical Activity Considerations for Using Physical Activity in Group-Based Programmes Repetitive and Rhythmic Activities This chapter presents students and practitioners with a rationale for incorporating physical activities within mental health practice. It will clarify terminology, summarize current evidence, and explain the mechanisms underpinning the proven benefits of physical activity. Acknowledging that this is a contested arena of inter-professional practice, the chapter will also critically analyse a distinctly occupational perspective of physical activity and engagement. To this end, it will consider the motivations for, and personal meanings of, being physically active within the context of individuals’ environments, and will reflect on how this informs person-centred goal-setting and intervention planning. Factors to consider when planning individual and group programmes utilizing physical activity and the evidence-base that underpins such interventions will also be discussed. The value of physical activity in promoting health and wellbeing has received significant attention within the last decade, placing it firmly on national agendas. The Chief Medical Officer in the UK (DH 2004) summarized evidence of the substantial, negative impact on both individual and public health of an inactive lifestyle. The report specifically identified the preventative and therapeutic potential of physical activity in relation to six chronic conditions: cardiovascular disease, obesity, diabetes, musculoskeletal problems, cancer and mental health problems. Since this influential document, the inclusion of physical activity within health-related policy and guidance has become widespread. There is an emerging consensus – based on research from disciplines such as medicine, exercise sciences, sports, psychology and public health – that exercise and physical activity can be important aspects of mental health promotion (Grant 2000; Hendrickx and van der Ouderaa 2008; Dugdill et al. 2009). Occupational therapy has a longstanding tradition of using physical activity for its therapeutic benefits, particularly within psychiatric institutions (Wilcock 2001). This was based initially on intuitive, practice-based reasoning that activities such as sports, dancing and horticulture improved mental wellbeing. Occupational therapists and occupational scientists are now developing an evidence base for a specifically occupational perspective of physical activity (Alexandratos et al. 2012; York and Wiseman 2012). Occupational therapists aim to facilitate individuals’ performance across a balance of occupations to support recovery, health, wellbeing and social participation (Creek 2003). This broad therapeutic purpose can be further magnified if physically active occupations are utilized. As the Chief Medical Officer for England (DH 2010) noted: the potential health benefits of physical activity are huge. If a medication existed which had a similar effect, it would be regarded as a ‘wonder drug’ or ‘miracle cure’ (p. 21). Caspersen et al.’s (1985) definition of physical activity as ‘any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that results in energy expenditure’ (p. 126) is still in use worldwide, including the UK Department of Health and the World Health Organization. The emphasis on physical activity (as distinct from exercise) in health policy and guidance is significant because it is broader and more inclusive; encompassing sports and leisure activities, but also including everyday activities arising during employment, housework, DIY, gardening or walking to school or work for example (see Table 14-1). This means individuals who would not normally choose strenuous exercise can still derive benefits from physical activity, which were previously only associated with vigorous activity (see Table 14-2). TABLE 14-2 Types of Physical Activities Related to Physiological Indicators Significantly, there may be additional advantages from moderate-intensity activity because it is less likely to incur health risks for individuals who are not acquainted with vigorous exercise (Dugdill et al. 2009). Research has indicated that health benefits appear to be proportional to the overall amount of physical activity (US Department of Health and Human Services 1996) because every increase in activity added some benefit. Therefore, the revised recommendation of the UK’s Chief Medical Officers (DH 2011a) for health promotion in adults is to aim for daily activity and to accumulate 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity over a week, which can be accumulated in periods of 10 minutes or more (see Table 14-3). TABLE 14-3 A Summary of Physical Activity Recommendations According to Age Source: Department of Health (DH 2011a). Note: Within this document there are also physical activity recommendations for early years (under 5 s) depending on whether or not they are walking. Emphasizing the total amount rather than the intensity of physical activity gives people more options for incorporating physical activity into their daily lives. This flexibility is important because Handcock and Tattersall (2012) caution occupational therapists that physical activity recommendations could become prescriptive and the targets could be overwhelming for service users. The promotion of moderate-intensity physical activity was found to offer considerable health gains; particularly to the least fit. However, despite these amendments, and the potential multiple health gains, it is still a major public health concern that participation rates are so low. According to the UK’s Chief Medical Officers (DH 2011a), only 40% of adult men and 28% of adult women met the previous recommendations for health. This meant 27 million adults in England alone were not active enough to benefit their health. Furthermore, there are distinct health inequalities in relation to physical inactivity according to income, age, gender, ethnicity and disability. Though participation rates for people with mental health problems are not specifically recorded, it could be postulated that some of the consequences of living with mental health problems – such as lethargy, lack of motivation, and anxiety arising from social and/or economic inequality and from stigma – could exacerbate the challenges that people may generally face in becoming more physically active. An important role for occupational therapists, therefore, is collaboration with individuals to analyse the complex factors influencing engagement, in order to incorporate physical activities within their daily occupational lives. The next section supports this kind of intervention by summarizing the evidence-base for the positive impact of physical activity on mental health and wellbeing. For the past decade, there has been a consensus regarding the benefits of physical activity on depression, mood, anxiety, stress reactivity and cognitive functioning, and on self-esteem and subjective quality of life (Grant 2000). More recently, empirical evidence for the positive impact of physical activity for people living with schizophrenia (Gorczynski and Faulkner 2010), dementia (DH 2011a) and substance misuse (Biddle and Mutrie 2008) has emerged. Indeed, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) recommends physical activity to varying degrees within its guidelines for dementia (NICE 2011a); depression (NICE 2009a); depression with chronic physical health problems (NICE 2009b) and schizophrenia (NICE 2009c). Additionally, improving the physical health of people with mental health problems is among the government’s top six mental health policy objectives (DH 2011b). Links between these objectives and the evidence-base for the role of physical activity in contributing to them are highlighted in Table 14-4. TABLE 14-4 Mental Health Policy Related to Physical Activity Sources: Fox et al. (2000); Department of Health (2004); Faulkner and Taylor (2005); Department of Health (2011a). A substantial evidence-base now exists detailing the positive relationship between physical activity and improved mental health and a strong mental health promotion perspective is developing concurrently with this (Dugdill et al. 2009). This mirrors the growth of health promotion within occupational therapy (COT 2008). It is a timely justification for developing roles incorporating physical activities such as health-promoting partnerships between occupational therapists and community/third-sector organizations. A more detailed consideration of the evidence for the use of physical activities with various service user groups will now be offered. This evidence has emerged within a diagnosis-based framework, though it is acknowledged that occupational therapy does not operate according to such delineations. However, accepting that this framework exists, this overview provides a resource for occupational therapists to draw on in their more person-centred work with individuals. The strongest evidence supports the benefits of physical activity for people living with depression. Seminal systematic reviews of research, such as Lawler and Hopker (2001), have concluded that there is an inverse relationship between physical activity participation and the occurrence of depressive symptoms. The UK Chief Medical Officers (DH 2011a) reported an approximately 20–30% lower risk for depression (and dementia) for adults participating in daily physical activity. Thus, it has a protective effect; validating a health promotion perspective. For those with clinical depression ‘the weight of evidence suggests that there is a causal connection between physical activity/exercise and depression reduction’ (Biddle and Mutrie 2008, p. 242). The NICE Guidelines for Depression specifically recommend physical activity as a psychosocial intervention for people with ‘sub-threshold depressive symptoms and mild to moderate depression’ and that physical activity programmes are delivered in groups by a ‘competent practitioner’ (NICE 2009a, p. 21). The term ‘competent practitioner’ is not defined, but occupational therapists with their specialist skills in activity are likely to be able to facilitate such groups depending on the nature of the activity, and the degree of collaboration with other professionals or physical activity specialists. Occupational therapists’ understanding of concepts such as self-efficacy, for example within the volitional construct of the Model of Human Occupation (Kielhofner 2008), is important when exploring participation with people who have depression. In addition to low mood, and associated anxiety, the person may also have thoughts and beliefs about their lack of competence that may further exacerbate difficulties. When setting goals, it is important to take account of a person’s self-perceived ability as well as their actual abilities, and grade interventions in order to achieve success. Although identifying individuals’ interests and values is essential, it should also be acknowledged that depression may limit satisfaction from activities previously enjoyed, or that people may report few current interests, even when their past ones were considerable. Therefore, physical activity may need to be integrated with approaches that also address psychological difficulties, such as cognitive-behavioural approaches, either in conjunction with, or in advance of, physical activities (Cole 2010). According to NICE (2011b) the evidence supporting physical activity as an intervention for people living with anxiety-related problems is considerably smaller than that related to depression. It is therefore an area that merits further research. However, there is support for a short-term role in symptom management through reducing the physiological reactivity to, and enhancing recovery from, psychosocial stressors. Evidence also suggests that physical activity may contribute to the reduction of non-clinical anxiety (Biddle and Mutrie 2008); that is, individuals outside mental health services whose wellbeing may be improved with physical activity. For some individuals, it may also reduce long-term vulnerability to anxiety but explanatory mechanisms for this are not definitively evidenced. An occupational therapist, however, may interpret these positive influences on long-term anxiety as being due to improved occupational performance and engagement in activities that have meaning, value and promote a sense of achievement. The educational aspect of the occupational therapist’s role may be important in countering any potentially negative consequences of physical activity – such as breathlessness, perspiration, and increased heart rate. While there is no evidence that exercise might induce panic or anxiety for people with anxiety disorders (Biddle and Mutrie 2008), these physiological responses to exercise may be distressing. Without education, reassurance and/or grading of the activity, these responses could lead to avoidant behaviours. Exercise can be used to promote physical self-worth and other positive physical self-perceptions such as those related to body image, which may be beneficial for people with low self-esteem (Grant 2000). These self-perceptions have been strongly correlated with individuals’ subjective sense of mental wellbeing and quality of life. Fox (2000) concluded that self-esteem is a significant factor influencing people’s choice of, and participation in, healthy behaviours. He analysed concepts of the physical self and associated perceptions of self-worth and saw that improvements, through exercise, in physical skills, competence, fitness, and body image could enhance self-esteem. Crucially, he also noted that perceptions of inadequacy in performing physical activities can lower self-esteem. Fox’s (2000) suggestion that self-esteem develops through an improved sense of competence, autonomy, and control over the body highlights the importance of grading and/or pacing to establish the ‘just right challenge’ (Yerxa 1998) that is integral to occupational therapy. The research consensus is that older adults who are fit display better cognitive performance than less fit older adults (Boutcher 2000) and there are indications that there is a reduced risk of dementia (DH 2011a). The influence of physical activity on quality of life may be more readily explained than improvements in cognitive functioning for people with dementia. For example, it may help with sleep, and improve mood since depression and anxiety are commonly experienced with dementia (NICE 2011a). Maintaining physical mobility and muscle strength also promotes independence in activities of daily living, thus avoiding frustrations associated with prolonged sitting and inactivity that may lead to agitation. This is supported by Laurin et al.’s (2005) review of various studies, which concludes that ‘physical activity can improve the functional status in frail nursing home residents with dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease’ and, importantly, that ‘there is no evidence that physical activity or exercise (including vigorous) is harmful’ (2005, p. 22). Occupational therapists will understand the importance of active ageing through the work of Clark et al. in the USA (2004) and subsequently the Lifestyle Matters programme in the UK (Craig and Mountain 2007) and as promoted in the NICE Guidelines for occupational therapy and physical activity interventions to promote the wellbeing of older people (NICE 2008). The fact that physical activity may help to mediate cognitive decline is further support for occupational therapists’ adoption of a health promotion role. Schizophrenia can have a major impact on individuals’ occupational functioning and quality of life. Neuroleptic medication is commonly prescribed to address positive symptoms such as delusions, hallucinations and thought disorders. Medication however, has little influence on negative symptoms such as lethargy, flattening of affect, social withdrawal and general lack of interest in activities. Indeed, the side-effects of medication such as drowsiness, weight gain, fatigue and dry mouth may contribute to this lack of interest (Mutrie and Faulkner 2003). A Cochrane review concluded that exercise significantly improved negative symptoms and that ‘given the physical, mental, and social benefits of regular exercise, clinicians should ensure their clients are becoming and staying active’ (Gorczynski and Faulkner 2010, p. 13). A wider systematic review by Holley et al. (2011) that also included qualitative studies focused on the role of physical activity on psychological wellbeing and found improvements in perceptions of autonomy, competence, social interest, psychological and physical health, and overall self-concept. People living with schizophrenia may also experience depression and anxiety and the beneficial effects described previously in relation to these disorders may equally apply to people living with schizophrenia. Occupational therapy’s focus on the contexts within which occupations occur is particularly pertinent to people living with major mental health problems since there are so many compounding influences on a person’s ability to participate in occupations in general, including physical activities. Such people may experience barriers related to stigma and social and/or economic deprivation that precludes access to community resources. Smyth et al. (2011) discuss this in the context of social exclusion and additionally report that the weight gain associated with neuroleptic medication may cause individuals to feel more self-conscious and uncomfortable when out in public. These factors serve to compound the difficulties of managing health-related lifestyle issues such as diet, physical inactivity and smoking. There is more evidence for the physical health benefits of exercise for people with alcohol dependence than for its influence on mental health problems. People who abuse alcohol often have poor physical health, such as decreased cardiovascular fitness (NICE 2011c), which can be developed through exercise and may contribute to improved physical self-worth. There is also some suggestion that exercise programmes promoting lifestyle behaviour change may contribute to developing self-control and coping strategies and alternatives to drinking (Biddle and Mutrie 2008). Donaghy and Ussher (2005) recognized the importance of interventions to enable participation in a range of new or previously enjoyed activities in order to contribute to the rehabilitation goal of maintaining abstinence or controlled drinking. However, they noted the particular challenges of working in this context, such as low starting levels of physical fitness, social isolation, lack of support and relapses into drinking. (This is considered in more detail in Ch. 28 regarding substance misuse.) The small-scale research of Ussher et al. (2000) reported that a programme incorporating exercise had a positive impact on the lives of the participants and that ‘the occupational therapist was shown to play a pivotal role in promoting fitness-oriented physical activity for those with substance misuse problems’ (p. 603). Consequently, it should be recognized that physical activity interventions can usefully be integrated with other therapeutic approaches such as cognitive behavioural therapy, self-help or support groups and practical lifestyle interventions. There is a dearth of published research concerning the benefits of physical activity amongst illicit drug users, although there is some suggestion that the improved sleep patterns associated with exercise are of benefit in the withdrawal stage from drugs, and anecdotal evidence of the popularity of physical activity as a therapeutic intervention (Pope 2003). Biddle and Mutrie (2008) suggest that improvements in physical health, diversion from drugs, and engagement with alternative social networks may help prevent relapse. This reinforces the efficacy of engagement in meaningful and valued activities within enabling environments. Additionally, people with alcohol and drug dependencies may also be susceptible to other mental health issues, particularly depression (Boden and Fergusson 2010), further reinforcing the potential for physical activity interventions. The UK government’s mental health outcomes strategy (DH 2011b) emphasized the connections between mental and physical health (see Table 14-4) and the Operating Framework for the NHS in England 2012/13 indicated that the physical healthcare of those with mental health problems required particular attention in order to reduce excessive mortality (DH/NHS Finance, Performance and Operations 2011). Specifically, people with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (Buhagiar et al. 2011) and depression (NICE 2009b) have higher morbidity and mortality rates resulting from coronary heart disease and stroke. Similarly, Naylor et al. (2012) note that ‘research evidence consistently demonstrates that people with long-term [physical] conditions are two to three times more likely to experience mental health problems than the general population’ (p. 3). NICE guidelines report that if a person has both depression and a physical health problem, then the functional impairments are likely to be much greater than either condition alone. Integrated treatment approaches to addressing physical and mental health needs are becoming prominent on health agendas (Naylor et al. 2012). Physical activity and the holistic practice of occupational therapy and are both uniquely placed in collaborating with other health professionals in responding to these needs. Despite the number of rigorous research studies, many researchers still urge caution when considering the methodological issues of measuring participation in physical activities (mainly via self-recording) and its impact on mental wellbeing (Daley 2008; Hendrickx and van der Ouderaa 2008). Furthermore, while meta-analytical Cochrane Reviews evaluating the impact of physical activity on schizophrenia (Gorczynski and Faulkner 2010) and depression (Mead et al. 2009) focus on randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews that meet ‘gold standards’ for research rigour, it should be noted that such research tends to analyse relationships between physical activity and alleviating symptoms, rather than on its contribution to engagement in satisfying and fulfilling life roles. This has presented occupational therapists with a challenge in providing an evidence-based justification for their interventions and demonstrates the need for further occupation-focused research to inform service development and commissioning. The benefits of physical activity are clearly wide-ranging and Biddle (2005), one of the key researchers in this field, has suggested that: physical activity may not be the ‘magic bullet’ we are looking for, but it comes a lot closer than most things! (p. xvii)

Physical Activity for Mental Health and Wellbeing

INTRODUCTION

Physical Health and Mental Health Promotion

PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND MENTAL HEALTH

The Nature of Physical Activity

Physical Activity Recommendations (DH 2011a)

Physiological Indicators

Light-intensity physical activity

Breathing rate is comfortable and conversation is easy

Moderate-intensity physical activity

Heart rate is raised and the pulse can be felt and the person feels slightly out of breath but still able to talk

There is a feeling of increased warmth, possibly accompanied by sweating on hot or humid days

The amount of activity needed to reach this varies from person to person depending on fitness and factors such as being overweight

Vigorous-intensity physical activity

Heart rate feels rapid, breathing is hard and the person cannot comfortably hold a conversation

Muscle strengthening

(weight training, working with resistance bands, carrying heavy loads, heavy gardening, push-ups, sit-ups)

The large muscle groups of the body – legs, hips, chest, abdomen, shoulders and arms – work or hold against a force or weight. Muscles will feel fatigued, and if using structured weight training, then exercised to the point where it is a struggle to complete another repetition

Age Group

Recommended Level of Activity

Children and young people (5–18 years)

Individuals should engage in moderate to vigorous activity for at least 60 minutes and up to several hours each day

Vigorous-intensity activities, including those that strengthen muscle and bone, should be incorporated at least 3 days per week

Adults (19–64 years)

Individuals should aim to be active daily, e.g. at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activity (in bouts of 10 minutes or more) per week, or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity spread across the week, or a combination of moderate and vigorous.

Individuals should also undertake activities to improve muscle strength on at least 2 days per week, and minimize extended periods of being sedentary (sitting)

Adults with disabilities (physical or mental health)

The same guidelines as above (for adults) apply. This may need to be adjusted for each individual depending on exercise capacity and any health or risk issues

Older adults (65 + years)

The same guidelines as above (for adults) apply

The Health Benefits of Physical Activity

Mental Health Policy Objectives (DH 2011b)

Related Evidence for the Impact of Physical Activity

More people will have better wellbeing and good mental health

Fewer people will develop mental health problems

Physical activity can improve mental wellbeing and also prevent the onset of mental health problems

More people with mental health problems will recover and experience a good quality of life

Physical activity can be an intervention to address mental health problems and can contribute to improved quality of life. It can be a means of coping with and managing mental health problems

More people with mental health problems will have good physical health

There is extensive evidence for a clear inverse relationship between physical activity and ill health. The strength of evidence and degree of efficacy varies for specific health outcomes

Fewer people will experience stigma and discrimination

Physical activity is normalizing and inclusive, as it can be done by all people regardless of diagnosis

Depression

Anxiety

Low Self-Esteem

Cognitive Problems and Dementia

Schizophrenia

Substance Misuse

Physical Health Problems

Using and Generating Research-Based Evidence

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree