Chapter 58 Physical Examination in Sleep Medicine

Abstract

Sleep Apnea

Overall Inspection

Sleep apnea often presents in association with obesity, which increases the prevalence 10-fold (20% to 40%).1 Obesity and, in particular, the central type of obesity (Fig. 58-1) are significant risk factors for OSA.2 They impose increased pharyngeal collapsibility through mechanical compression of the pharyngeal soft tissues and decreased lung volume through CNS-acting signaling proteins (adipokines) that may alter airway neuromuscular control.2,3 OSA may independently predispose individuals to worsening obesity as a result of sleep deprivation, hypersomnia, and disrupted metabolism.4

Figure 58-1 Central obesity in OSA.

(From Kryger MH. Atlas of clinical sleep medicine. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2010.)

Sleep apnea is also associated with endocrinopathies such as hypothyroidism5,6 and acromegaly.7 Hypothyroidism is a known cause of secondary OSA; oropharyngeal airway myopathy, edema, and obesity predispose patients to upper airway collapse and obstruction. Acromegaly results from excessive growth hormone, resulting in enlarged growth of the craniofacial bones, enlargement of the tongue (macroglossia), and thickening and enlargement of the laryngeal region; all of these factors can contribute to upper airway obstruction. Goiter, which is associated with acromegaly and hypothyroidism as well as a euthyroid state,8 can contribute to OSA (Fig. 58-2). Other conditions contributing to upper airway narrowing include Down syndrome and deposition disorders such as mucopolysaccharidosis and amyloidosis.

Figure 58-2 Goiter.

(From Kryger MH. Atlas of clinical sleep medicine. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2010.)

Craniofacial Factors

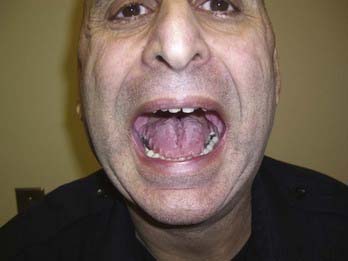

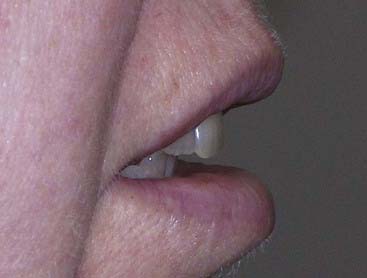

Cephalometric measurements reveal that subjects with OSA have significant changes in the size and position of the soft palate and uvula, volume and position of the tongue, hyoid position, and mandibulomaxillary protrusion compared with controls. Mandibular retrognathia (Fig. 58-3) and micrognathia (Fig. 58-4), which cause the tongue to rest in a more superior and posterior position, impinging on the upper airway, can be detected on examination, especially by observing the patient from the side. A scalloped tongue (Fig. 58-5) may accompany micrognathia. Men with retrognathia or micrognathia may grow a beard to compensate for this anatomic variant. Crowded teeth (Fig. 58-6) and overjet (Fig. 58-7), with the mandibular teeth excessively posterior to the maxillary teeth, often accompany retrognathia or micrognathia. Racial differences in cephalometric properties probably play a major role in conferring risk for OSA in the absence of obesity. For example, in Chinese patients with OSA, a more retropositioned mandible was associated with more severe OSA, after controlling for obesity.9 In Japanese patients with OSA, micrognathia was a major risk factor.10 Children and adults with Down syndrome frequently have sleep apnea most likely related to a combination of craniofacial abnormality and macroglossia.

Figure 58-3 Mandibular retrognathia contributing to OSA.

(From Kryger MH. Atlas of clinical sleep medicine. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2010.)

Figure 58-4 Mandibular micrognathia contributing to OSA.

(From Kryger MH. Atlas of clinical sleep medicine. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2010.)

Figure 58-6 Crowded teeth indicate a small mandible, contributing to OSA.

(From Kryger MH. Atlas of clinical sleep medicine. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2010.)

Figure 58-7 Overjet contributing to OSA.

(From Kryger MH. Atlas of clinical sleep medicine. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2010.)

Patients with OSA have an increased pharyngeal narrowing ratio, which is defined as a ratio between the airway cross-section at the hard palate level and the narrowest cross-section from the hard palate to the epiglottis.11

Nasal Factors

Examination of the nasal airway should focus on anatomic abnormalities that may contribute to nasal obstruction. These may be congenital, traumatic, infectious, or neoplastic in etiology (Fig. 58-8).

Examination of the Pharynx

There are two well-established classifications to determine the relation of the tongue to the pharynx. The Mallampati classification was first described as a method for anesthesiologists to predict difficult tracheal intubation.13 The Friedman classification identifies prognostic indicators for successful surgery for sleep-disordered breathing, combining palate position with tonsillar size.14

The Mallampati classification is as follows:

Figure 58-9 Mallampati class I.

(From Kryger MH. Atlas of clinical sleep medicine. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2010.)

Figure 58-10 Mallampati class II.

(From Kryger MH. Atlas of clinical sleep medicine. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2010.)

Figure 58-11 Mallampati class III.

(From Kryger MH. Atlas of clinical sleep medicine. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2010.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree