Posttraumatic Seizures

Frederick G. Langendorf

Timothy A. Pedley

Nancy R. Temkin

Introduction

The risk for epilepsy is increased at least threefold in patients with head injury compared with the general population.4 Head injury is a major risk factor, comparable with bacterial meningitis, heroin abuse, or a family history of seizures.32,33 Each year in the United States, about 1.5 million people sustain a traumatic brain injury.64 Although trauma accounts for only about 5% of all epilepsy cases, this is still a problem of considerable magnitude. More importantly, it is a potentially preventable cause of epilepsy.

The link between head trauma and epilepsy raises a number of important issues. A rational approach to treatment and prevention requires knowledge of the incidence of posttraumatic seizures and the specific aspects of injury that are associated with the development of epilepsy. How should posttraumatic seizures be treated, and is there a role for prophylactic antiepileptic drug therapy? Finally, because seizures develop after a known injury to the brain, posttraumatic seizures offer the opportunity to investigate mechanisms of epileptogenesis.

Historical Perspectives

That head injuries could be associated with acute seizures was known to Hippocrates. Duretus (1527–1586) attributed epilepsy in an 18-year-old man to a skull fracture that had occurred 6 years earlier. Head injury appears in 19th-century tabulations of causes of epilepsy, although it ranked well behind fright and masturbation in importance.61 Modern concepts of head injury and epilepsy derive from studies of British and American veterans of four major 20th-century wars.11,55

Definitions

Implicit in the designation posttraumatic seizures is the notion that the injury not only preceded, but also caused the seizures. Posttraumatic seizures are classified as early (occurring within 1 week of injury) or late (occurring more than 1 week after injury); in some studies “early” encompasses a longer interval, or means the phase of recovery from the acute effects of injury. Early seizures include a subgroup of immediate or impact seizures, which occur at the time of, or immediately after, the injury. Early seizures are acute symptomatic seizures. Late seizures are remote symptomatic seizures; they may be single or multiple. Conventionally, only recurrent late seizures represent posttraumatic epilepsy. In practice, posttraumatic seizures and posttraumatic epilepsy are sometimes used interchangeably.

Head injuries have traditionally been divided into two categories: Penetrating injuries from “missile” damage (mostly gunshot wounds) and closed injuries from “blunt” trauma (mostly caused by falls, motor vehicle accidents, and assaults not involving firearms). There has not been uniform agreement about what constitutes mild, moderate, and severe head injury. Mild injury generally excludes evidence of intracranial structural pathology and neurologic abnormalities other than brief loss of consciousness or amnesia. Severe injury implies significant structural damage to the brain (either focal or diffuse), or coma, encephalopathy, or amnesia lasting more than 24 hours. Victims of head injury can be stratified more objectively based on the neurologic examination using the Glasgow Coma Scale.36

Epidemiology

Head Injury

In the United States, the annual incidence of hospitalization or death from traumatic brain injury is about 100 per 100,000 population.64,65 Men are more often affected than women. The age-related incidence peaks are in young adults 15 to 24 years of age and in the elderly. Next most affected are young children. The incidence of fatal head injury is about 20 per 100,000. Among survivors of moderate to severe head injury, only about half recover to baseline in such functional domains as home management, financial independence, and social integration.18 It is estimated that 5.3 million Americans (2% of the population) are living with disability as a result of a traumatic brain injury.64

Seizure Studies

It is difficult to establish the incidence of posttraumatic seizures accurately because of a number of methodologic pitfalls. Case ascertainment varies from study to study. For example, head injuries may be noticed only because of a seizure. In some patients, other risk factors for seizures may be present, including pre-existing epilepsy, previous head injury, or alcoholism. Ascribing acute seizures to the effects of brain injury may be confounded by alcohol withdrawal, medication toxicity, or metabolic encephalopathy. In determining the incidence of late posttraumatic seizures, acute symptomatic seizures should be excluded, and the expected incidence of unprovoked seizures occurring in the general population must be taken into account. Many patients are lost to follow-up, and these may not be representative of the study population. As a result of all of these pitfalls, estimates of posttraumatic epilepsy tend to be inflated.

Early Seizures

Late Seizures

In the Vietnam Head Injury Study,55 53% of veterans who suffered a missile injury eventually experienced at least one seizure, with multiple seizures occurring in the great majority. The relative risk in the first year was 580. In about half the patients, the first seizure occurred within 12 months of injury, but in more than 15% of patients, seizures did not develop until 5 or more years later and the relative risk remained elevated at 10 years. In earlier studies of veterans with military head injuries, late seizures occurred in 35% to 45%.11

In Jennett’s large series of patients in Oxford and Glasgow who were hospitalized because of nonpenetrating head injury, late seizures occurred in 5%.34 However, of those patients with severe trauma, late seizures occurred in up to 35%.

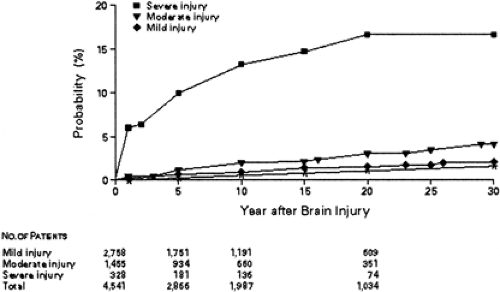

In a seminal work, Annegers et al. studied civilian head injury (mostly, but not exclusively, nonpenetrating injury) in Olmsted County, Minnesota, and determined the incidence of late seizures, taking into account the incidence of unprovoked seizures in the general population.3,4 Children under 15 constituted 38% of the study population. The 5-year cumulative probability of seizures for mild, moderate, and severe injury was 0.7%, 1.2%, and 10%, respectively (Fig. 1). Late seizures occurred in 7.4% of children and 13.3% of adults with severe trauma, with the elderly at still greater risk. The relative risk of late seizures (single or multiple) for mild, moderate, and severe injury was 1.5, 2.9, and 17.0, respectively. After severe injury, about half of the first seizures occurred in the first year, but the risk of a first late seizure remained elevated even 10 years later. After mild injury, this risk had largely subsided at 4 years.

The demonstration (for the first time) of a link between mild head injury and seizures is tempered by the very low relative risk. It follows from a relative risk of 1.5 that an unprovoked seizure following a mild head injury is twice as likely to be unrelated to the injury as it is to be related.

Seizure Recurrence

Early seizures are followed by late seizures in 25% to 35% of adults; early seizures are less predictive of late seizures in children.3,16,37 The relative risk is in the range of 3 to 5,4,5,19 but risk factors for early and late seizures are similar, and early seizures did not appear to confer a large independent risk of late seizures in a multivariate analysis.4

A first late seizure will have a high risk of recurrence.3,12,55 In one study of moderately to severely injured patients (penetrating and nonpenetrating) with a first late seizure, recurrence occurred in 47% at 1 month and 86% at 2 years, with at least four additional late seizures in half of these patients.30

Immediate seizures have been studied phenomenologically and epidemiologically in Australian rugby players. When not associated with other evidence of significant injury, they appear not to significantly increase the risk for later seizures. They may be no more than a transient symptom of concussion.45,46

Risk Factors

For penetrating injury, retained metal fragments, intracranial hematoma, persistent neurologic deficits, and degree of brain volume loss as estimated from computed tomography (CT) images were all associated with increased seizure risk.55 For nonpenetrating injury, depressed skull fracture and intracranial hematoma (both subdural and intracerebral) are risk factors for both early and late seizures.4,15,34 Multiple cerebral contusions may place a patient at particularly high risk.20 The presence of parenchymal blood, whether caused by trauma or stroke,39 appears to be an important element in the development of seizures. Coma duration and Glasgow Coma Scale score correlate with occurrence of both early and late seizures.20 There is some controversy as to whether intracerebral hemorrhage14,16 or severity of diffuse encephalopathy42 best predicts seizures. Seizures are seen in a higher proportion of abusive injuries than accidental injuries in children; the abusive injuries were more serious by other measures as well.8

Genetic influences have long been suspected as a factor in the development of posttraumatic seizures. Although some investigators have reported that a family history of epilepsy is more common in subjects in whom epilepsy does develop following head injury than in those in whom it does not,12,21 the most careful studies to date were unable to demonstrate any increase in the frequency of seizures among relatives of probands with head injury.50,56 Similarly, the Vietnam Head Injury Study failed to show any increase in family history of seizures among those in whom posttraumatic epilepsy developed.55 Despite a lack of evidence, it is possible that genetic susceptibility increases the risk for epilepsy in people with milder injuries, individuals who constitute a small proportion of the posttraumatic seizure population.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree