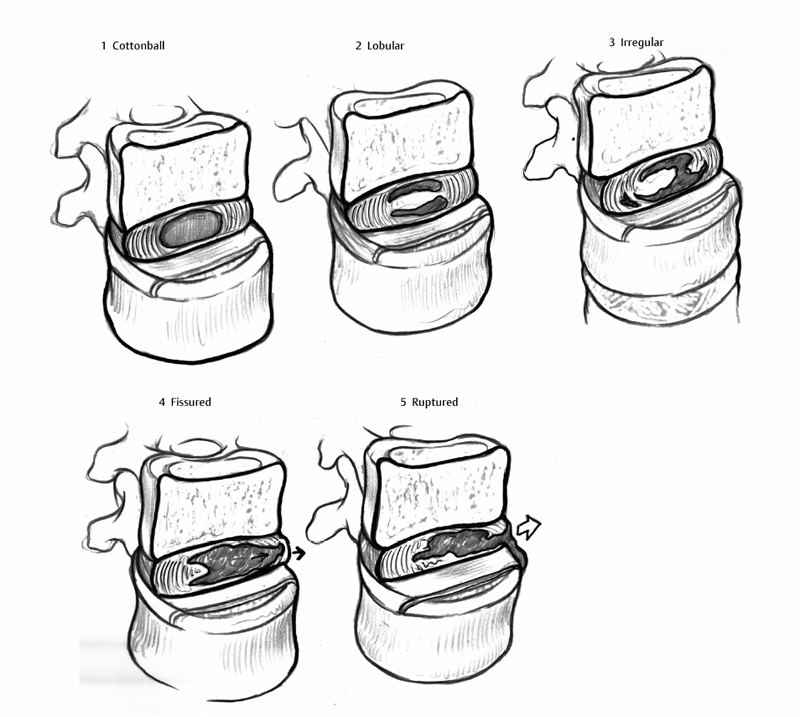

15 Provocative Testing (Discography) Eugene J. Carragee and Angus S. Don Lumbar back pain is extremely common, but most cases are self-limiting with no functional deficit. Nevertheless, even when diagnostic imaging reveals only degenerative changes, some people become seriously debilitated in the absence of any serious pathology or instability. Is there a specific “pain generator” responsible for these symptoms? Provocative discography has assumed the role of identifying the pain generator with the aim of directing specific treatment, which has not been without its controversies. In this chapter, we will review the history, technique, and rationale behind provocative discography. The accuracy of diagnosis in many low back pain (LBP) syndromes is uncertain without a clear gold standard.1 Furthermore, the results of surgical treatment for chronic LBP are not highly effective unless specific structural abnormalities are identified (e.g., pyogenic infection, isthmic spondylolisthesis). In the three randomized controlled trials (RCTs) using cognitive-behavioral therapy versus fusion for LBP with only common spondylosis on imaging studies, only small differences were noted between the fusion and nonoperative groups. Mixed outcomes from these studies demonstrated some relative advantage to the nonsurgical group (fewer complications, better coping strategies) and some relative advantage to the fusion group (a modest improvement in the Oswestry Disability Index in the British study).24 Even in the original RCT by Fritzell et al,5 which showed some outcome results in favor of the fusion cohort for LBP, high levels of success were not common. Excellent results were reported in 16% of the fusion group, as opposed to 6% in the usual care group.5 Clinical and epidemiologic research has shown a strong association of psychosocial and neurophysiologic comorbidities with axial pain syndromes. These predictors, appearing to confound a purely structural etiology of common LBP disability, need to be taken into account when considering the concept of a specific pain generator, and the results of provocative discography, especially when surgery is considered. Schmorl and Junghanns6 introduced discography as an anatomic study to evaluate the internal structure of the cadaveric intervertebral disc. In 1941 Lindgren presented a case of a normal disc injected with contrast material, in a paper read before the Swedish Radiology Society. This case was not published.7 Stimulated by the work of Lindgren and Schmorl, in 1944 Knut Lindblom injected discs with red lead in vitro. He was the first to report the presence of radial ruptures in the posterior and posterolateral disc anulus.8 Carl Hirsch9 was the first to note that symptoms from ruptured discs could be exacerbated by injection of normal saline directly into the affected disc; thus, he used pain response as a diagnostic parameter (provocative disc injections) to determine the pathologic disc level in a case of lumbago and sciatica. In the same year, Lindblom modified Hirsch’s technique to include the radiologic injection of contrast material (Diodrast) to visualize radial tears of the anulus. The diagnostic criteria were also expanded to include not only the radiologic appearance of the disc but also the patient’s response to the injection, thus giving birth to “provocative discography.”10 In the United Stated, discography was first performed at the Cleveland Clinic (Cleveland, OH) in the early 1950s by Wise and Weiford.11 In 1960 Ulf Fernstrom12 suggested that there are both mechanical and biomechanical causes for back and leg pain, following the observation that pain can occur regardless of whether there is any detectable nerve compression. Collis and Gardner13 in 1962, reported in their study of a 1000 patients who underwent discography that it was “superior” to myelography in the evaluation of lumbar disc disease, meaning discography was often abnormal in subjects with symptoms when myelography was not. Feinberg,14 in an evaluation of over 2000 patients, described the characteristics of the abnormal discogram patterns. Some of these findings remain common descriptors in clinical discography today. He also surmised that annular tears played a significant role in the pathophysiology of back and leg pain, when the pain could not be accounted for by nerve compression alone. The early published reports expounded the usefulness of discography as a test, but in 1968 Holt became the first to challenge its validity.15 He looked at a series of 30 prisoners without a history of LBP and reported a 37% false-positive rate. He concluded that lumbar discography is unreliable as a diagnostic test.15 Holt’s study has been the subject of much criticism based on several methodologic flaws by Simmons et al16 in 1988 and Walsh et al17 in 1990. The flawsincluded the exclusion of 23% of injected discs as they were judged invalid due to technical difficulties in performing the procedure. All the subjects were prisoners—Holt performed a significant number of annular injections known to be painful, and he used a highly irritating contrast medium. He did not include positive pain response as a criterion for positive injections, and the criteria for a positive test were based primarily on radiologic images.16,17 At the same time of Holt’s study, Wiley et al18 reported on a large series and believed that discography was most valuable in the evaluation of patients with pain and no definite herniation. The concept of an internal disc disruption syndrome with back pain as its primary symptom was introduced by Crock in 1970.19 The introduction of newer, safer contrast material developed for myelography occurred around the same time,20 which allowed for safer imaging. In 1984 the introduction of computed tomographic (CT) discography enabled the imaging of intradiscal architecture.21 Bernard demonstrated that plain discography combined with postdiscography CT gives structural information not attainable by other means of that period.22 The more frequent use of manometry has recently been of interest. Manometry allows for the measurement and correlation of incremental injectable pressure with the pain response. The concept of measuring intradiscal pressure is not a new one; Nachemson as early as 1959 attempted to record intradiscal pressure.23 It has been hypothesized that this technique may permit more specific interpretation and diagnosis and therefore may guide treatment with a higher degree of accuracy.24,25 Despite the increasing technical sophistication surrounding the clinical use of discography, it has also been the subject of ongoing uncertainty and controversy. Some clinicians believe discography is of clinical value and recommend its use in certain indications. Others believe that unless the clinical accuracy and utility of the test can be established using conventional evidence-based medicine methodology, the test should remain investigational. On the one hand, indications for discography in the management of LBP have been suggested by the Executive Committee of the North American Spine Society Diagnostic and Therapeutic Committee.26 In this paradigm, discography should be performed only when a patient has failed an adequate course of nonoperative treatment, and other noninterventional tests (e.g., magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) have failed to provide sufficient diagnostic information. These guidelines give wide latitude for clinical application and define general uses for discography to include but not be limited to the following26: The Guidelines of the American Association of Neurological Surgeons/Congress of Neurological Surgeons (AANS/CNS) recommend that discography not be used as a “stand-alone test” and that positive discography with normal MRI findings should be considered a contraindication to surgical or other invasive interventions. These recommendations suggest a negative test may be most accurate and helpful in limiting fusion length and further caution against diagnosing multiple positive discs with this method.27 On the other hand, the AHCPR Guidelines recommend against any use of discography for the evaluation of acute LBP syndromes. Similarly, the European Cost Guidelines recommend against the use of discography in chronic LBP syndromes as being without demonstrable utility of validity. Finally, the Bone and Joint Decade Task Force on Neck Pain and Associative Disorder found there was no evidence to support provocative discography of the cervical spine in patients with neck pain. This group also noted that pain response to provocative discography cannot accurately distinguish between subjects with and without neck pain.28 Most authors of the numerous review articles on discography recommend taking a preliminary history to ascertain that there is no systemic infection, or local infectionat the surgical site, no underlying bleeding diathesis, and no inappropriate psychological status of the patient.29–36 These would all be considered contraindications to the procedure. Note should also be taken of any prior back or disc surgery. Prior imaging studies need to be carefully assessed to exclude other pathology and guide the number and order of the discs to be injected. The patient’s pain should be evaluated, including: The patient’s history of allergies, especially to local anesthetic or contrast media, needs to be assessed, as should the need for prophylactic medication. The patient should have full informed consent prior to the procedure, which should include discussion of the discography-associated risks (see Complications section below). Provocative discography requires the patient to be awake and coherent enough to answer questions about the reproduction of pain. Therefore, it is imperative to use sufficient local anesthetic and as little general sedation to keep the patient comfortable, yet avoid disorientation, uncooperative behavior, or somnolence. The patient should ideally be able to recall the procedure well, as the referring surgeon will often ask procedure-related questions at follow-up. The use of antibiotics in discography has been of some debate. The administration of a broad-spectrum antibiotic, such as cefazolin, clindamycin, or ciprofloxacin, has been advocated by some authors. This can either be administered intravenously or added to the intradiscal suspension.37 Care should be taken with positioning to optimize visualization and reducing the difficulty of the procedure. Several discographers prefer to place the patient in a prone or lateral position. Others have described a position in which the patient’s body is slightly oblique and at a 45-degree angle to the bed and rotated forward.38 This position allows for less movement during the procedure, obviates the need for restraints, and improves visualization of the lumbosacral junction, thereby reducing the risk of abutting the iliac crest when inserting the needle.38 The fluoroscope should then be moved into position. The technique of preliminarily tilting the C-arm to visualize the optimal route into the disc, particularly at the lumbosacral junction, was emphasized by Schellhas.33 Standard sterile preparation of the back should be performed. Local anesthetic should be infiltrated into the skin and possibly underlying musculature. The superior articular pillar (SAP) should not be anesthetized as this may spread anesthetic to the foramen and margin of the disc, increasing the likelihood of a false-negative response. An oblique extradural approach is used through the safe zone lateral to the SAP following the adjacent endplate, using a coaxial two-needle approach. The use of a curved distal needle tip has been advocated to circumvent the SAP and allow positioning of the tip into the mid disc.39 The placement of needles on the contralateral side to the patient’s habitual pain has also been recommended by some authors to avoid interfering with the pain response by inadvertently anesthetizing the spinal nerve to the adjacent disc.29,33 This concern has not been confirmed.40 Placement of the needle in the center of the disc is confirmed by biplanar fluoroscopy. Needles are usually placed in at least three consecutive levels. A low osmolar, nonionic contrast has been recommended for discography. The patient should be unaware of the precise moment of injection, the level or levels injected, and the amount injected. The following should be monitored: Fig. 15.1 Contrast distribution in discography and peridiscal space according to the classification of Adams et al.41 Cottonball: no signs of degeneration, soft white amorphous nucleus. Lobular: mature disc with nucleus starting to coalesce into fibrous lumps. Irregular: degenerated disc with fissures and clefts in the nucleus and inner anulus. Fissured: degenerated disc with radial fissure leading to the outer edge of the anulus. Ruptured: disc has a complete radial fissure that allows injected fluid to escape; can be in any state of degeneration. The criteria for a positive discogram are controversial and often have extended beyond the traditional pain reproduction on injection. However, the primary criteria for a “positive” provocative discogram are usually defined as both the reporting of “significant” pain upon injection (for instance 6/10 or 3/5 on a pain scale) and reproduction of usual symptoms in terms of both quality and distribution (concordance). These basic criteria were proposed by Walsh et al17 and others and remain the basic test information needed for interpretation. Multiple other criteria have also been suggested with the aim of improving the reliability and validity of the test (Table 15.1). It has been proposed that discs should be classified into low (<15 or 20 psi) or high (>50 psi) depending on the recorded pressure (above opening values) at time of significant pain response.24,42 Those discs that are associated with a severe pain response at low pressures have been termed “chemically” sensitive discs as opposed to discs that are only sensitive at high pressures, and termed “mechanically” sensitive. This theory contends that chemically sensitive discs are painful because of the exposure of annular nerve endings or nearby neural structures to the leakage of irritating substances in daily activities. The mechanically sensitive disc theory is based on the high-pressure injection mechanically distending the anulus and simulating a mechanical loading, which is presumed to be the inciting event in daily activities. Unfortunately, pain with injection at low pressures has been repeatedly seen in asymptomatic subjects.42 The suggestion has been made that more than one or two positive disc injections should invalidate the study, as all levels are therefore indeterminate. The logic of this exclusion contends that multiple painful injections at different levels may represent a generalized hyperalgesic effect diffusely about a painful structure.

History

Indications and Guidelines

Technique for Provocative Lumbar Discography

Patient Evaluation

Anesthesia

Antibiotics

Positioning

Approach

Assessment

Criteria for a Positive Provocative Discogram

| Discographic Criteria | Threshold for Positive Test |

| Pain intensity | ≥6/10 or 3/5 |

| ≥7/10 | |

| Concordance | Pain is “similar” but not exact |

| “Exact” pain only | |

| Annular disruption | Dye must distribute through fissure to or through anulus80 |

| Pain behavior | Facial expressions must be used to confirm verbal pain response17 |

| Control disc injection | “Negative” injection (minimal or discordant pain) required adjacent to proposed “positive” disc80 |

| “Normal” injection (i.e., no pain) |

Complications

The reported complications associated with discography have apparently declined over time, with a variety of different serious complications reported prior to 1975, including meningitis, discitis, intrathecal hemorrhage, arachnoiditis, severe reaction to accidental intradural injection, and damage to the disc itself.43

One of the most serious complications reported is that of discitis, believed to be due to penetration of bacteria into the disc by a contaminated needle.44 It was suggested that a preoperative intravenous prophylactic dose of antibiotics be given or added to the radiographic contrast, which would all but eliminate the risk of discitis.37 The incidence of discitis was reported to be reduced from 2.7% to 0.7% by using a two-needle technique.45 More recently, Willem et al45 followed 435 patients after discograms without antibiotic prophylaxis for 3 months and reported no incidence of discitis (95% CI, <0.15% risk). They also conducted a thorough analysis of the literature and concluded that the risk of discitis by patients with no antibiotic cover over nine studies was 0.25%.45

The most frequent complication after discography is increased pain. Tallroth et al46 reported an incidence of 81%. However, this generally resolves with analgesia over 1 to 2 weeks. Isolated cases have also been reported of urticaria,22 retroperitoneal hematoma,47 and acute disc herniation.48 In psychologically vulnerable individuals, such as those with serious somatic distress, provocative discography can initiate an additional chronic pain syndrome in subjects with no significant preexisting low back illness.49,50 The use of discography in patients with multiple somatic complaints or diagnosed somatization disorder should be carefully considered and usually avoided.

There were early concerns that discography could induce premature degeneration of the disc; however, in a study of 188 patients over 10 to 20 years after discography no demonstrable independent effect on the disc was found as a result of discography.51

Scientific Foundation

The basis of pain in patients with chronic LBP in the absence of any serious structural disease has long been the source of debate. For the small percentage of patients with chronic incapacitating LBP, the question remains as to why they are so severely affected, while others with similar degenerative findings are minimally affected or even asymptomatic. This has led to the search for a so-calledpain generator. Various anatomic sites have been implicated, briefly enjoyed popularity, and then discredited, including common osteophytes, facet sclerosis, minor lumbar scoliosis, etc. The concept of the disc as being the pain generator has persisted and the pathognomonic finding in a degenerative disc, which can be definitively and reliably linked to serious axial pain, is the Holy Grail that many investigators seek.

The opposing view holds that the pain generator approach is misplaced after serious underlying diseases have been excluded. These researchers point to the epidemiologic trends and poor results of treatments directed at the spine per se. As imaging studies show similar pathology in those suffering mild discomfort or no LBP at all and those with severe pain, the difference in clinical manifestation must be due to other nonstructural factors. Treatment should then be directed at the other causes, such as central pain processes, psychological factors, social disincentives, poor coping strategies, etc., and aim at restoring function and supporting adaptive techniques.

Anatomic Basis

The concept of the disc being an intrinsic source of pain assumes that common disc abnormalities and internal architectural changes of the anulus also innervated. The innervation of the disc, has of itself, been a source of controversy and whether the cause of the pain is biomechanical or chemical. In discography, the injected substance exerts a mechanical strain on some annular fibers41 the pain that is generated is believed to arise when these annular fissures or nuclear herniations extend into the outer third of the anulus.52 In adult degenerative discs, nerve endings from branches of the sinuvertebral nerves, the gray rami communicantes, and the lumbar vertebral rami consistently innervate the outer third of the dorsal, lateral, and ventral aspects of the anulus, respectively.53 Neurotransmitters associated with nociception have been detected in the posterior longitudinal ligament and anulus. Therefore, a reasonable anatomical basis exists for the disc to be a pain generator.

Confounding Factors in Spinal Pain Perception

The pain reported with disc injection can be influenced by multiple local and generalized factors. Although pain may come from several local sources, several common factors have the potential to suppress or amplify pain perception. These factors need to be carefully considered when evaluating a patient’s history, examination, and responses during provocative disc injections.54

- Adjacent tissue injury. This effect occurs when damage to tissues causes an amplification of pain perception by increasing the local inflammatory and nociceptive processes, resulting in secondary neurologic sensitization of the local nondamaged area. This hyperalgesic effect is especially relevant in patients with LBP with serious structural disease at one or more levels (e.g., unstable spondylolisthesis or disc herniation with root compression) that may sensitize adjacent levels to provocative testing.55

- Tissue injury in same or adjacent sclerotome. Lower spinal elements that have the same or adjacent afferents shared with a sclerotome that has sustained injury may increase the sensitivity of the spinal elements on which provocative testing is performed. This confounding effect is important when considering the specificity of discography at sites of similar embryonic origin to a known pathologic structure.

- Local anesthetic. Perception of pain may be decreased at a local site by local anesthetic injection. This may be the source of false-negative results in provocative discography if the careful placement of the anesthetic is not well controlled.

- Chronic pain syndromes. Chronic pain from sites near the lumbar spine (chronic pelvic pain, failed hip arthroplasty, etc.), or distant from the lumbar spine (chronic headache, neckpain, etc.) may increase pain sensitivity and complicate LBP syndromes. The effect on the neural axis may be reflected either globally or locally. Furthermore, chronic pain syndromes are associated with depression and narcotic use habituation, which of themselves affect pain perception, and have been demonstrated to affect pain intensity with discography in experimental subjects.55

- Narcotic analgesia. The effect of narcotics occurs at multiple levels to decrease the pain thresholds, intensity, and affective response, and may act as a confounder in provocative discography in the perception of pain.55–57

- Narcotic habituation. Chronic narcotic habituation in the absence of increased narcotic intake may act to decrease pain tolerance in the absence of accustomed opioid intake. It can also be associated with depression and sleep disturbances.

- Psychological stressors. Psychological distress from any etiology may increase pain perception. The threshold to a painful response with disc injection may be decreased and the perceived pain intensity and affective response can be increased.56,58,59 In this situation, discography may erroneously identify otherwise minor structural processes, contributing little to the overall chronic pain illness, as the cause of an extremely painful and gravely disabling condition.

- Social/cultural factors. A depressed pain perception or a dissociation of pain perception and functional loss mayresult from overriding social or cultural factors. Certain cultural groups are less expressive or emotional when describing their chronic pain,60 and this may decrease the specificity of provocative discography.

- Secondary gain.There are common clinical situations in which an exaggerated pain response will result in a real or perceived social benefit or monetary compensation. This may have direct effects on reporting during provocative discography. Patients may have conflicting incentives in reporting pain intensity rating or degree of pain concordance, particularly if large economic fortunes are perceived to be at stake.

In summary, the subjective pain response and quality reported with provocative discography must be evaluated in context of the patient’s clinical, psychological, and social circumstance.

Diagnostic Accuracy

For a diagnostic test to be of use it has to be reliable and valid and have good utility. The following section will examine the reliability, validity, and utility of provocative discography as a diagnostic test by current methodology standards used in evidence-based medicine.

Reliability

Reliability is the extent to which repeated application of the same test in the same circumstance will produce the same result (i.e., precision or reproducibility).61 It refers to the capacity of a test to give the same result on repeated application. Although reliability does not imply nor guarantee validity (i.e., high sensitivity and specificity), unreliability will probably make a test insufficiently sensitive or specific to be valid.62

Reliability of Discogram Images

Walsh et al17 used five raters to evaluate the discograms initially into a three-point scale (normal, degenerate, or degenerated and herniated), but later a two-point scale was used. Using a consensus rating the adjusted percent agreement was 96%.17 Adams et al41 introduced the fluoroscopic classification of discogram images on cadavers in 1986 and reported 87% reproduction of their results when repeated 6 months later. Later studies have looked at the interobserver and intraobserver agreement in the clinical setting. In the clinical setting, the kappa value for the paired interobserver agreement is excellent at 0.77.63 Absolute interobserver and intraobserver agreement occurred in 82 levels (62%).63

Reliability of Pain Interpretation

Walsh and colleagues in their 1990 work used a two-camera technique to videotape the fluoroscopic image of the discogram as well as the patient’s reactions to the injection and the responses to postinjection interview.17 Pain was evaluated by two of the authors who assessed the patient’s pain-related behavior as well as the patient’s pain intensity as measured on a pain thermometer. Interobserver reliability was good for the intensity of pain and pain-related behavior (Pearson correlations, 0.986 and 0.926, respectively).17 Regarding the similarity of the pain, this was in agreement 88% of the time between the two observers.17 Similar agreement on image interpretation was found in several experimentally designed discography studies.64,65

Reliability of Results after Repeated Injections

There are no good reliability data on the pain response or concordancy reporting by patients undergoing discography. It is not clear that repeated testing after a short interval (several hours) or with another set of needle placements on another day would yield the same pain intensity response or concordancy assessment.

Validity

Provocative discography aims to diagnose the presence or absence of a disc lesion as the sole or primary pain generator responsible for an individual’s LBP illness. The problem remains that there is no commonly accepted pathoanatomic gold standard for confirming the diagnosis of primary discogenic pain. Sackett and Haynes1 have described the criteria for the evidence-based evaluation of the validity for diagnostic tests. The four phases of scrutiny are shown in Table 15.2. Several clinical and experimental studies have been done to examine the validity of provocative discography.

| 1. Do test results in patients with the target disorder differ from those in normal people? |

| 2. Are patients with certain test results more likely to have the target disorder than patients with other test results? |

| 3. Does the test result distinguish patients with and without the target disorder among patients in whom it is clinically reasonable to suspect that the disease is present? |

| 4. Do patients who undergo this diagnostic test fare better (in their ultimate health outcomes) than similar patients who are not tested? |

Evaluation of Pain Response in Asymptomatic Subjects

Psychological Factors in Patients Undergoing Discography

A few studies have investigated the potential impact of psychological factors on discographic pain provocation in clinical practice. Block et al66 found that patients with elevated scores on the hysteria and hypochondriasis scale of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory were significantly more likely to report pain during injection than those without elevated scores. Similarly, patients who indicated unusual patterns on pain drawings were more likely to report pain provocation during injection of a nondisrupted disc than those without unusual pain patterns.67

Validity of the Concordancy Response

Whether patients can accurately identify the source of LBP by the quality of sensation when a disc is injected is not clear. Carragee et al performed discography in a group of 8 patients asymptomatic for LBP who had undergone posterior iliac crest bone graft for reasons other than thoracolumbar surgery.65 Most of these patients experienced low back and buttock pain for some months following the procedure, which is of a similar distribution to what is normally considered typical lumbar discogenic pain. When discography was performed in these subjects, each was asked to compare the quality and location of the injection pain to the usual iliac crest bone graft site pain. In 9 of the 24 discs (37.5%) injected, the pain produced was similar or exact pain, and three of the eight patients (37.5%) would have met the criteria for a positive discogram.

In clinical practice, “positive” concordant lumbar discography has been reported in subjects with known nondiscogenic pain syndromes. Pain from spinal neoplasm (osteoid osteoma), pelvic pathology, and fracture has been confused with the pain of disc injection.68

In summary, the validity of the concordancy rating as confirming the source of axial pain has not been proven. Anecdotal reports and small experimental studies indicate the finding of a similar pain perception with disc injection cannot be used with a high degree of confidence to confirm a discogenic source of back pain.

Discography in Subjects with Minimal Low Back Pain

Critical to the validity of provocative discography as a test is the ability to distinguish between a clinically relevant pain generator as the cause of serious disabling back pain as opposed to a disc that may be associated with minimal or inconsequential pain. Derby and colleagues24 performed discography in a group of 16 subjects with minimal or occasional LBP, which did not require medical care or were experiencing disability. In this group, 5 of 16 (31%) subjects had a pain response equal to 5/10, and 2 of 16 (12.5%) had a response of 6/10.

In another study, 25 subjects with mild persistent LBP with no functional limitation, who were not seeking medical attention for their problem, underwent provocative discography.69 Nine of the 25 patients (36%) had discographic injections of one or more discs, which were both significantly painful and concordant. All positive discs had annular disruption, and all had negative control discs. By the usual proposed criteria, these were fully positive disc injections for clinically serious discogenic pain illness.

These findings indicate that even if a disc is correctly identified as being capable of producing some perception of pain with injection, this disc may actually contribute only minimally to the overall pain illness. Consequently, aggressive treatment (e.g., fusion) of a minimally painful disc, although “positive” with discography, will be unlikely to be highly effective.

Utility

For any diagnostic test to be useful (i.e., have clinical utility), the use of the test should be shown to improve outcomes of relevant clinical features. The question remains whether discography appears to have demonstrable utility in the management of patients with chronic LBP. To date, no randomized controlled trial of discography has tested this hypothesis. The data from less rigorous studies are mixed.

Colhoun et al70 studied 195 patients in whom discography was performed and who later underwent surgery, generally fusion. This retrospective study compared two groups, with and without positive preoperative provocative discography, in whom surgery was technically successful. The group with a positive image and pain provocation had an 88% success rate, whereas in the group with a positive image but negative pain provocation the success rate was only 52%. However, the two groups were not similar at baseline. Furthermore, systematic biases causing some patients to be examined with discography and others to proceed directly to surgery were unexamined.

Madan and colleagues71 recently studied the outcomes of 73 consecutive patients following spinal fusion who had been evaluated with and without preoperative discography. The authors performed all fusions with discography for a set time interval, then without discography for a matching time interval. The patients were well matched in terms of demographic data and psychometric and radiographic features. At a minimum of 2 years follow-up, there was no significant outcome difference. These authors concluded provocative discography as an additional screening tool was not very helpful in improving patient outcome after circumferential fusion for discogenic back pain.

Finally, Cohen et al72 compared the outcomes literature for fusion when performed in studies using discographyand compared these to studies in which fusion was performed for presumed discogenic pain on the basis of MRI or CT alone. They found no systematically improved outcomes in the studies using discography as a selection criterion. The authors concluded that the use of discography had not been proved to improve the outcome of surgical treatment for degenerative disc disease.

Outcome as Gold Standard

The diagnostic validity of positive discography was assessed by Carragee et al73 in a highly selected and controlled cohort where positive results were compared against a gold standard of substantial clinical improvement after removal of the supposed pain generator (disc and posterior anulus) and successful interbody arthrodesis. Thirty-two patients with LBP and a positive single-level low-pressure provocative discogram underwent spinal fusion. Generic surgical limitations/morbidity were controlled by comparison to the clinical outcomes of a strictly matched cohort of 34 patients having a well-accepted single-level lumbar pathology (unstable grade I or II isthmic spondylolisthesis). The proportion of patients who met the minimal acceptable outcome was 29 of 32 (91%) in the spondylolisthesis group and 13 of 30 (43%) in the presumed discogenic pain group. This study demonstrated that positive discography was not highly predictive in identifying bona fide isolated intradiscal lesions primarily causing chronic LBP illness. Despite removal of the pain generator as diagnosed by discography, approximately half the patients continued with significant pain and impairment. This is the first study to apply an external gold standard evaluation of the diagnostic validity of discography in any manner.

Other Studies

Moneta et al52 demonstrated that in clinical practice discs with annular disruption were more likely to be painful with injection than those with disc degeneration alone. There was considerable overlap, however, between these two groups, and it is unclear whether there were more or less false-positive or false-negative injections in those patients with extensive annular disruption.

Laslett et al74 found that patients coming to discography who had more persistent pain between LBP episodes, a greater feeling of “vulnerability” in the neutral zone, and a centralization phenomenon with lumbar posturing, tended to have more painful disc injections than those without these findings. This group as a whole had longstanding chronic pain, severe psychological distress, and chronic opioid use. Again, which if any of these injections correlated with either true “discogenic pain” or a positive response to proposed treatment was not reported.

Many authors have noted a correlation between bright signal annular fissures (high-intensity zone [HIZ]) seen on MRI and a painful response to disc injection. Aprill and Bogduk75 reported that an HIZ was “pathognomonic” of severe symptomatic discogenic pain. Further investigation, however, found that HIZ are commonly found in completely asymptomatic subjects and that injection of discs with HIZ in asymptomatic subjects was frequently very painful at low pressures.76,77

Summary

It is clear that standard methods to assess the reliability, validity, and utility of provocative discography do not strongly support this test. Test reliability is poorly or inadequately documented. Validity testing in asymptomatic subjects indicates few false-positive results in the subset of persons with no chronic pain processes, no psychological distress, no litigation history, and less annular disruption. Although sometimes meeting this profile, this is not the typical patient coming to discographic evaluation for chronic disabling LBP illness with otherwise age-appropriate studies. The best-case scenario of subjects without these comorbidities and a positive low pressure, single-level disc injection still only found a 50% positive predictive value of “treatable” discogenic pain syndrome. The utility of discography, even in the best-case setting, has not been proved. Data from one well-matched controlled study showed no utility.

| Best case for a valid and useful test result |

| 1. Negative discogram (next to other pathology—e.g., spondylolisthesis) |

| 2. Positive single level, normal psychological status, normal social profile (no worker’s compensation) |

| Unclear or doubtful validity or usefulness |

| 1. Two-level positive, normal psychological status, normal social profile |

| 2. Postoperative discs, normal psychological status, normal social profile |

| 3. Intermediate (at risk) psychometrics, equivocal pain behavior, single-level |

| Poor validity, usefulness, and serious risk of misdirecting care |

| 1. Spine with multilevel pathology |

| 2. Abnormal or chronic behavior |

| 3. Abnormal psychometric findings |

| 4. Disputed compensation cases |

Source: Adapted from Carragee EJ, Hannibal M. Diagnostic evaluation of low back pain. Orthop Clin North Am 2004;35:7–16, with permission.

Conclusion

Fusion, arthroplasty, or intradiscal surgery for presumed discogenic LBP is increasingly being performed.78 The proponents of provocative discography believe that this test accurately identifies discogenic pain and may help direct care.79,80 The scientific basis for the test has not been proved, however, and there is no pathoanatomic gold standard to confirm the diagnosis as commonly made in clinical practice. It must be remembered that the subjective patient response is fundamental to discography, and interpreting the test in different settings must be considered. Therefore, if the test is used at all, a clinician needs to balance the discography results based on the patient’s history, clinical, and other diagnostic findings.

When all factors are considered, the recommendations in Table 15.3 can be made.

References

1. Sackett DL, Haynes RB. The architecture of diagnostic research. BMJ 2002;324:539–541

7. International Spinal Society. Recommendations for lumbar discography. Sci News 1997;2:80

15. Holt EP Jr. The question of lumbar discography. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1968;50:720–726

19. Crock HV. A reappraisal of intervertebral disc lesions. Med J Aust 1970;1:983–989

23. Nachemson A. Measurement of intradiscal pressure. Acta Orthop Scand 1959;28:269–289

25. O’Neill C, Kurgansky M. Subgroups of positive discs on discography. Spine 2004;29:2134–2139

26. Guyer RD, Ohnmeiss DD. Lumbar discography. Spine J 2003;3: 11S-27S

29. Anderson MW. Lumbar discography: an update. Semin Roentgenol 2004;39:52–56

30. Tehranzadeh J. Discography 2000. Radiol Clin North Am 1998;36: 463–495

31. Anderson SR, Flanagan B. Discography. Curr Rev Pain 2000;4: 345–352

32. Guarino AH. Discography: a review. Curr Rev Pain 1999;3:473–480

33. Schellhas KP. Diskography. Neuroimaging Clin N Am 2000;10: 579–596

34. Ortiz AO, Johnson B. Discography. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol 2002;5: 207–216

35. Carragee EJ, Alamin TF. Discography: a review. Spine J 2001;1: 364–372

37. Osti OL, Fraser RD, Vernon-Roberts B. Discitis after discography: the role of prophylactic antibiotics. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1990;72:271–274

47. McCulloch JA, Waddell G. Lateral lumbar discography. Br J Radiol 1978;51:498–502

53. Bogduk N. The innervation of the lumbar spine. Spine 1983;8: 286–293

55. Siddall PJ, Cousins MJ. Spinal pain mechanisms. Spine 1997;22: 98–104

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree