38

CHAPTER

![]()

Psychiatric Comorbidities

Sarah K. Rivelli

Approximately half of all patients with epilepsy have psychiatric symptoms or disorders. Psychiatric comorbidity is an important predictor of health and quality of life among patients with epilepsy and requires careful evaluation and treatment. This chapter will review psychiatric comorbidity commonly encountered among patients with epilepsy, the use of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) in psychiatry, the risk of suicide among patients with epilepsy, adverse psychotropic effects of AEDs, and the risk of seizure associated with psychotropic medications.

PSYCHIATRIC COMORBIDITIES

Anxiety

Anxiety and anxiety disorders appear to be common among patients with epilepsy. The main anxiety and related disorders as classified by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-5 (DSM-5) (1), and estimated prevalence in patients with epilepsy is listed in Table 38.1.

The unpredictability of seizures and their negative impact on functioning may lead to anticipatory anxiety in some patients. The areas of the brain involved in anxiety include the amygdala and hippocampus. The amygdala mediates autonomic and endocrine responses through the output to the hypothalamus and avoidance behavior through output to the periaquedecutal gray matter. The hippocampus mediates the reexperiencing of fear and its affective component. Pharmacologic treatments of anxiety reduce excessive output of these neurons (2). Antiepileptic agents that potentiate GABA-ergic inhibition, such as benzodiazepines, are also effective antiepileptic agents.

Panic Attacks and Panic Disorder

Interictally, patients with epilepsy have been found to have high rates of panic attacks, with up to 20% of patients having at least one panic attack. Panic attacks are characterized by an abrupt surge of intense fear or intense discomfort that reaches a peak within minutes and is associated with a variety of physiological symptoms such as shortness of breath, chest pain, and nausea. A diagnosis of panic disorder (PD) is made if they meet DSM criteria (see Table 38.1); prevalence rates in epilepsy range between 5% and 10% (2).

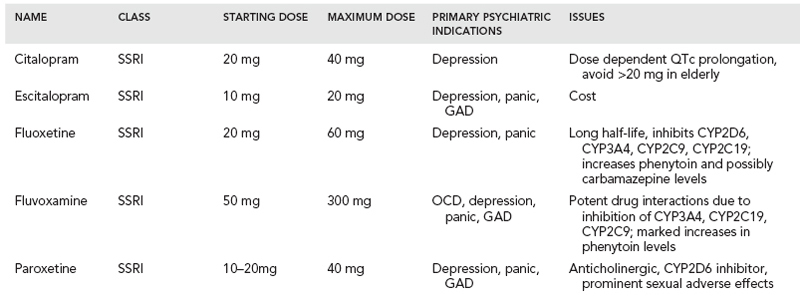

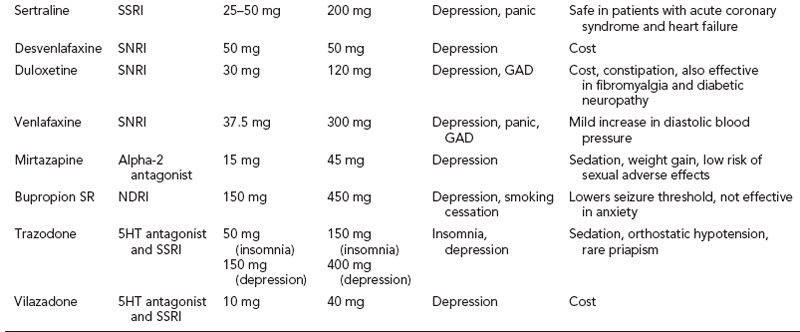

Benzodiazepines and antidepressants are equally efficacious in PD, however antidepressants are considered preferable due to the risk of abuse, tolerance, withdrawal, and negative effects on cognition and motor function with benzodiazepines. Clonazepam and alprazolam are approved by the FDA for PD. Alprazolam appears to have more liability for abuse and generally should be avoided. Serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) approved for PD include sertraline, venlafaxine, paroxetine and fluoxetine (see Table 38.2). SSRIs are better tolerated and appear to be equally efficacious to tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) such as imipramine and clomipramine that are approved by the FDA for PD. Moreover, depression and anxiety disorders tend to be comorbid and antidepressants offer benefit for both disorders, while benzodiazepines do not. One strategy in the highly anxious distressed patient is to start both an antidepressant and a benzodiazepine simultaneously, and then taper the benzodiazepine after 4 to 6 weeks, once the antidepressant has started to take effect and a mean effective dose has been achieved. Among patients with epilepsy, a careful slow taper of benzodiazepine, such as a decrease by 10% to 20% daily, must be ensured with concurrent adequate AED treatment on board. There is some weak evidence that gabapentin may be helpful with panic, and thus it may be a useful adjunct in certain patients with seizures and comorbid panic attacks.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is highly effective for panic disorder and as effective as pharmacotherapy. There are often challenges with access to high-quality treatment, however. When available, referral for CBT should always be made.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) may be more common among patients with epilepsy, though studies have not demonstrated this consistently (2). It is a common, yet debilitating, disorder that is frequently comorbid with depression in particular, and affects about 5% of the general population in the United States. SSRIs, serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and TCAs all have proven efficacy in GAD. FDA-approved treatments include sertraline, escitalopram, paroxetine, venlafaxine, and duloxetine (see Table 38.2).

TABLE 38.1 Anxiety and Related Disorders

DISORDER | KEY DIAGNOSTIC FEATURES | ESTIMATED PREVALENCE IN EPILEPSY |

Panic disorder | Recurring panic attacks Worry about attacks and/or maladaptive behavior May be accompanied by agoraphobia (fear of public places) At least four associated physical or psychological symptoms: palpitations, sweating, trembling, shortness of breath, feelings of choking, chest pain, nausea or abdominal distress, feeling dizzy or faint, chills or hot, paresthesias, derealization or depersonalization, fear of losing control, “going crazy” or dying. | 5% to 10%; up to 20% with isolated panic attacks |

Generalized Anxiety Disorder | Excessive anxiety and worry about a number of issues for at least 6 months At least three of six associated symptoms: Restlessness or keyed up, easily fatigued, difficulty concentrating, irritability, muscle tension, insomnia or restless sleep. | 3% to 12% |

Social anxiety Disorder | Marked fear or anxiety about one or more social situations The social situations almost always provoke anxiety Avoidance of social situations Lasts at least 6 months | 3% to 7% |

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder | Exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence Symptoms last at least for 1 month and include: | 1% |

| Intrusive recollections, distressing dreams, flashbacks, psychological or physical distress at exposure to internal or external cues related to trauma Persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with the traumatic event Negative alterations in cognitions and mood associated with the traumatic event Marked alterations in arousal and reactivity associated with the traumatic event(s), such as irritable behavior and angry outbursts, reckless or self-destructive behavior, hypervigilance, exaggerated startle response, problems with concentration, sleep disturbance |

|

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder | Obsessions – recurrent thoughts, urges, images that are intrusive and unwanted; attempts to neutralize or suppress | 1% to 5% |

| Compulsions – repetitive behaviors or mental acts in response to obsessions that are time-consuming and cause impairment |

|

Buspirone is a 5 hydroxytryptamine 1A receptor (5HT1A) partial receptor agonist, which is thought to lead to its anxiolytic effects. It has been found to be as effective as diazepam in treating GAD; however, it takes up to 6 weeks at a total daily dose of at least 30 to 45 mg (given in two to three divided doses) for full effect. Benefits of buspirone include that it is nonsedating with no risk for abuse or dependence and does not lead to withdrawal symptoms or seizures when discontinued. On the other hand, patients and providers tend to abandon the treatment prior to achieving benefit due to the delay in noticeable effect. Carbamazepine and other CYP3A4 inducers tend to lower the effective level of buspirone, and thus titration to maximal dose of 20 mg three times daily may be required.

Hydroxyzine has been found to be significantly more efficacious than placebo in treating GAD and is low cost. However, it causes sedation, which can be undesirable among patients already taking an anticonvulsant with such side effects. Quetiapine is effective in treating GAD according to a few randomized controlled trials (RCT); however, its negative impact on glucose and lipid metabolism, risk for tardive dyskinesia (TD), and tendency to cause orthostatic hypotension suggest that other agents are preferable for the treatment of GAD.

Pregabalin is the anticonvulsant agent with the strongest evidence for treating GAD, with demonstrated efficacy in short-term and longer-term trials (3). It is approved in Europe for the treatment of GAD. The effect size of pregabalin in treating GAD appears to be at least as large as that for SNRIs, and pregabalin may be better tolerated. Thus, pregabalin is the first-line anticonvulsant for a patient with comorbid epilepsy and GAD.

TABLE 38.2 Nontricyclic Antidepressants

Social Anxiety Disorder

Social anxiety disorder is characterized by extreme fear of social situations, leading to avoidance behavior that significantly impairs function. It appears to be equally prevalent among patients with and without epilepsy, at about 7% (2). SSRIs appear to all be equally efficacious, with high-quality evidence for escitalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, and venlafaxine. Low-quality evidence suggests that gabapentin and pregabalin are effective in treating social anxiety disorder, and these may certainly be useful approaches among patients with epilepsy.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) comprises a diverse group of symptoms beyond anxiety that include intrusive recollections, avoidance of stimuli associated with the traumatic event, marked arousal and reactivity, and negative cognitions and mood (see Table 38.1). Thus, treatment of this disorder tends to be complex and dependent on which symptom clusters are most debilitating. SSRIs are often considered first-line treatments with decent evidence in favor of paroxetine and sertraline, which are FDA approved for this indication.

Studies examining anticonvulsants have largely been negative, such as well-designed trials of lamotrigine and topiramate that did not demonstrate significant symptom improvement (2). Second-generation antipsychotics such as risperidone and quetiapine may be useful adjuncts to SSRIs in some patients with PTSD, but adverse metabolic effects and risk for TD argue for other treatment approaches whenever possible.

PTSD-specific CBT has consistently been shown to be efficacious in PTSD and generally includes elements of desensitization and exposure. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) is an effective, though somewhat controversial, treatment for PTSD. It has been shown to be as effective as CBT and is recommended by the American Psychiatric Association, among others, for the treatment of PTSD. EMDR’s impact likely comes from elements of exposure therapy, and the eye movements are actually irrelevant to its efficacy. Thus, if available, referral to EMDR is certainly reasonable because of its structured, manual-based approach that comprises desensitization and exposure, with proven efficacy in PTSD. Finally, given the complexity of the constellation of symptoms in PTSD, it is recommended that such patients generally receive specialty mental health care and referral is recommended.

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder

Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) tends to be among the most disabling psychiatric disorders and requires specialty treatment that includes psychotherapy, such as CBT or exposure therapy, and pharmacotherapy. ODC is characterized by the presence of recurrent intrusive thoughts, recollections, or images that are unwanted and distressing (obsessions) accompanied by repetitive behavior or mental acts in response to obsessions that are time consuming and impair functioning (Table 38.1). High-dose SSRIs appear to be required in treating OCD, which may increase seizure risk (2). FDA-approved agents for OCD include fluvoxamine, paroxetine, and sertraline (Table 38.2). Fluvoxamine is an SSRI that appears to have only modest efficacy in treating depression, but is helpful in OCD in particular. The use of fluvoxamine is confounded by pharmacodynamic interactions due to inhibition of CYP1A2 which also metabolizes tizanidine, and CYP2C19, which metabolizes diazepam and phenytoin.

Clomipramine is a highly serotonergic TCA which is the most effective agent in treating OCD and appears to have more effect than SSRIs. However, it is associated with a higher proconvulsant risk, may cause cardiac conduction delay, has more anticholinergic side effects and leads to weight gain, thereby limiting its use. Lamotrigine is one anticonvulsant that may be helpful in OCD; low quality evidence suggests that it may be an effective augmentation strategy for patients that fail to respond adequately to SSRIs. Patients with OCD will likely be referred to specialty mental health care, particularly for CBT which is the mainstay of treatment.

Depression

Prevalence and Clinical Presentation

The prevalence of active depression among people with epilepsy has been estimated at 23%, and lifetime prevalence at 13% in community-based samples (4). People with epilepsy have at least a twofold increased odds of having depression (5). Depression assessed by a self-report screening questionnaire, the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), was found in 29.3% of patients presenting to an epilepsy clinic (6).

Depression is one of the main determinants of low health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in epilepsy, and subsyndromal and major depression appear to have an equally negative impact on HRQOL (7). Of note, patients with well-controlled seizures tend to have lower depression scores than those with persistent seizures in various studies. Depression is chronic in about half of patients, with atypical features being more common among those with epilepsy. Atypical features include predominant irritability, anxiety, and hypersomnia. Anxiety disorders are frequently comorbid, occurring in about half of all patients with depression. Symptoms of depression include a persistently sad or low mood, loss of pleasure in activities, decreased or increased appetite and/or weight, insomnia or hypersomnia, psychomotor agitation or retardation, fatigue or loss of energy, feelings of worthlessness or guilt, diminished concentration, recurrent thoughts of death and/or suicidal ideation. The diagnosis of depressive disorder is given when symptoms persist nearly every day for most of the day over a 2-week period (1).

Transient depressed mood may occur preictally, periictally, or postictally. Interictal dysphoric disorder tends to be chronic and includes labile mood, depressive and irritable symptoms, and appears distinct from depressive disorder and generally improves with improved seizure control. In fact, complete seizure control appears to reduce the risk for depression overall. Postictal depression has been found to occur in 43% of patients with poorly controlled epilepsy (6).

Differential Diagnosis

Important in the differential diagnosis is considering the impact of AEDs on mood, including the negative psychotropic effects of some AEDs that cause fatigue, lethargy, and cognitive slowing and may be mistaken for depression. One approach is to avoid the use of AEDs with negative psychotropic properties among patients who appear at increased risk for mood disorders, such as those with a positive personal or family history. Agents thought to increase the risk of developing depression include benzodiazepines, barbiturates, tiagabine, vigabatrin, topiramate, zonisamide, and levetiracetam (8). This relationship with depression is likely more related to sedating effects and cognitive slowing from these agents than an increase in sadness or loss of pleasure seen in depression per se, though dysphporia has been described with topiramate and levetiracetam in particular. Also of note, AEDs such as carbamazepine, phenytoin, and primidone may decrease the serum level of antidepressant medications via CYP induction, leading to a relapse in depression in patients who had previously responded to treatment with an antidepressant (5). Finally, patients undergoing epilepsy surgery appear at increased risk for depression, with 20% to 30% having a depressive episode in the first 6 months postsurgery (5).

Underlying Mechanisms

There are likely many mechanisms at play in the association between epilepsy and depression. One factor is that epilepsy is a stressor, particularly because seizures are unpredictable and debilitating and often negatively impact social functioning, leading to learned helplessness and reduced concept of self-efficacy, all of which may lead to depression. Epilepsy can be a burden to patients due to stigma, disability, and the need to restrict activities such as driving or swimming and may contribute to the development of depression. AEDs may also facilitate the development of depression or lead to symptoms such as fatigue and cognitive slowing and exacerbate depression. Examination of clinical factors in epilepsy has not yielded any consistent relationships between epilepsy duration, focus site, or lateralization, except for some evidence suggesting that complex partial seizures are more common among patients with depression and epilepsy compared to those with epilepsy alone (7).

Treatment

There have been virtually no randomized controlled trials evaluating the treatment of depression among patients with epilepsy, and thus treatment is based on data from studies of the general population of depressed patients (5). SSRIs (Table 38.2) are considered first-line therapy and are all equally efficacious in treating depression (5). Bupropion is generally avoided in patients with epilepsy due to its proconvulsant effect.

Before starting treatment with an antidepressant, ensuring that there is no personal or family history of mania or hypomania is important, as antidepressant treatment can provoke a switch into mania and is associated with more frequent episodes of bipolar disorder, called rapid-cycling bipolar disorder. Mania is characterized by a period of persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood lasting at least 1 week and accompanied by inflated self-esteem, decreased need for sleep, excessive talking that is often pressured, racing thoughts, distractibility, increased goal-directed activity, or psychomotor agitation (1). Hypomania is characterized by a shorter duration of only 4 days and symptoms tend to be less severe. Referral to a psychiatrist may be warranted to clarify diagnosis or to manage severe manic symptoms.

Treatment of depression should include titration up to a maximal dose of an antidepressant in order to achieve full response, and a trial at the effective dose for at least 6 weeks prior to switching therapies or declaring treatment failure. If a patient fails to have remission of the majority of symptoms after two adequate trials of an antidepressant, referral to a psychiatrist is certainly warranted. Note that changes or initiation of AEDs may reduce serum levels of antidepressants, and thus high doses of antidepressants may be required. Inducers of CYP3A4 such as phenytoin, carbamazepine, and phenobarbital and high-dose oxcarbamazepine and topiramate may reduce serum levels of SSRIs, requiring an increase in dose by as much as 25% to 30% to maintain antidepressant efficacy.

Adverse effects of SSRIs include restlessness and nausea, which tends to be transient. Sexual disturbances are common, which include decreased libido and delayed or absent orgasm; paroxetine appears to have the highest propensity to cause such effects, while citalopram, escitalopram, and mirtazapine much less so. SSRIs are also associated with increased risk of osteoporosis and doubling of fragility fracture risk, and thus careful attention to bone density is needed for patients who are also taking high-osteoporotic-risk AEDs such as phenytoin.

Psychotherapy

A number of psychotherapies have been shown to be effective in treating depression in high-quality RCT. CBT has specifically been shown to be efficacious among patients with depression and epilepsy and might be considered first line for such patients, particularly if anxiety is also present. Some data suggest that CBT among adolescents with epilepsy may prevent the development of depression, and may help with patients coping with epilepsy as a chronic condition.

Referral

Referral to a psychiatrist is warranted for refractory depressive episodes, diagnostic clarification, psychotic symptoms, severe mania, and concern for suicide risk.

Somatic Therapies

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is a highly effective treatment for depression, leading to rapid treatment response and benefit in refractory patients and those with psychosis or catatonia. ECT has also been used in rare instances to treat refractory status epilepticus since it increases the seizure threshold over time. Limitations to ECT include lack of focal stimulation, negative cognitive effects such as anterograde amnesia, stigma, lack of access, and the need for general anesthesia. Vagal nerve stimulation (VNS) is approved both for treatment-resistant depression and refractory epilepsy. Mood improvement has been demonstrated among patients receiving VNS for epilepsy and it may be a viable treatment for patients with comorbid depression and epilepsy (7).

Repetitive transmagnetic stimulation (rTMS) involves stimulating superficial nerves in the brain by placing a magnetic coil near the skull that creates a magnetic field. Low-frequency stimulation leads to decreased excitability, while high-frequency stimulation increases excitability of targeted regions. In depression, rTMS is used to increase excitability of the left prefrontal dorsal cortex with well-demonstrated improvement in mood. rTMS is approved for the treatment of depression, but does not appear to be as potent a treatment as ECT, its role may be reserved for less refractory patients. Low-frequency stimulation, on the other hand, has been examined to decrease activity of epilepsy foci, but so far has generally produced negative results. It is currently unclear if rTMS might prove useful among patients with epilepsy and depression. Seizures provoked by rTMS have been virtually unknown since the establishment of safety guidelines in the mid-1990s, but a small increased risk of seizure has been reported among patients with epilepsy receiving high-frequency rTMS that ranges from 0% to 3.6%.

Psychosis

Psychosis occurs in as many as 9% to 10% of patients with epilepsy. Psychosis may be seen in ictal, periictal, and postictal phases of epilepsy. Bitemporal seizure focus and seizure cluster are documented risk factors for psychosis in epilepsy (9). Persistent psychosis may arise from complex partial status due to activity in the limbic and/or frontal lobes and appear very similar to that of primary psychosis clinically (10). Distinguishing features that favor epilepsy include confusion, inattention, and/or altered consciousness. Some so-called interictal psychosis may actually be due to subclinical epileptic discharges and appears to occur predominantly in temporal lobe epilepsy, while clinically it is often indistinguishable from primary psychosis (10).

There is some evidence that seizures and psychosis might be antagonistic or reciprocal, at least in some patients. This antagonism is demonstrated by “false normalization,” which is the paradoxical normalization of the EEG during an increase in psychotic symptoms. Similarly, it has been observed that for some patients, when they are more psychotic, they have fewer seizures (9).

Psychotic symptoms in epilepsy most typically include hallucinations and delusions; aura may also be present. Other symptoms such as persistent thought disorganization, impaired social functioning, or bizarre behavior are less common among patients with psychosis in epilepsy. On the other hand, neuropsychological testing comparing patients with epilepsy and those with schizophrenia did not show significant differences in cognitive profiles (9). Most experts agree that the most common substrate for psychosis in epilepsy is limbic seizure activity, but this is not specific, nor sufficient, for the production of symptoms that may vary widely and include sensory phenomena as well. Postictal psychosis tends to follow recurrent seizures generally after a lucid interval of 24 to 48 hours and is generally time limited, resolving within 2 weeks.

Though hallucinations, illusions, and delusions might suggest different clinical diagnoses in psychiatry, there is less evidence for distinct areas or networks in the brain being responsible for such symptoms (11). In fact, stimulation of the same area even within the same individual can produce widely different clinical symptoms, while stimulation of different areas can produce similar phenomena, which suggests widely distributed neuronal networks as the basis for such phenomena (11).

Aggression

Some patients have episodes of aggression that are clearly linked to seizure activity and improve with seizure control. Such a diagnosis is made preferably with video EEG (vEEG) recording, documenting seizure during aggression. The aggressive behavior seen in epilepsy tends to be poorly organized, less purposeful, and of brief duration. Though not definitive, seizures presenting as aggression are thought to arise from the amygdala and limbic structures (9). AEDs that might be particularly helpful for such patients include those that are used for mania and aggression in psychiatry, namely, valproate and carbamazepine. Aggression occurring only in the interictal period may be more related to underlying psychiatric disorders such as mood disorders or personality disorders (9).

Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) has been found to be more common among patients with epilepsy, with an estimated prevalence among children with epilepsy of 14%, while patients with ADHD have about 2.5-fold risk of developing epilepsy (9). Overall, adequate treatment with AEDs appears to improve attention among these patients. Treatment with stimulants, such as methylphenidate, appears to be safe in patients with ADHD and epilepsy. EEG abnormalities that have been well documented in ADHD include increased fronto-central theta band activity and increased theta/beta power ratio during rest compared to controls. Significant heterogeneity is noted among patients with ADHD, however, and the role of EEG in diagnosis or monitoring has not yet been elucidated.

SUICIDE RISK, EPILEPSY, AND ANTIEPILEPTIC DRUGS

Patients with epilepsy report a high lifetime prevalence of suicidal thoughts, plans, and attempts and have a three- to fourfold increased risk for suicide (8). Among patients having epilepsy and known psychiatric disorder, the risk climbs to a 13-fold increased risk (8). The period immediately following a diagnosis of epilepsy is a particularly vulnerable period; if a psychiatric condition is also present, the risk is almost 30 times higher than the general population (8). Patients with temporal lobe epilepsy also appear to be at elevated risk. Another vulnerable group is patients undergoing epilepsy surgery, where the risk for mood disorders is highest in the first 3 months postsurgery and confers increased risk for self-harm (9).

Examination of suicide risk due to AEDs has been confounded by the low frequency of suicide; retrospective analyses; combining studies of AEDs with widely varying mechanisms; combining studies where AEDs are prescribed for pain, epilepsy, psychiatric, and other indications together; and lack of adjustment for known risk factors for suicide such as depression or prior suicidality. Suicidal thoughts and behaviors were not assessed systematically in studies a priori, but were captured when coded as adverse events in the studies. Moreover, it is difficult to build a case for harm without evidence of reasonable potential mechanisms by which the agents might lead to such risk, which is impossible given the diverse pharmacologic agents grouped together for analyses and that epilepsy trials often allowed polytherapy.

Interestingly, naturalistic studies have not supported an increased risk of suicide associated with AEDs among patients with epilepsy, and the literature includes contradictory results (12). There is some signal in the literature that lamotrigine, topiramate, and, to a lesser degree, levetiracetam are associated with an increased risk for suicidal thoughts or behavior, but this needs to be more thoroughly examined in prospective trials with careful assessment for risk factors and the occurrence of suicidality.

People with epilepsy are more likely to have depression and other psychiatric comorbidities, and thus are at increased risk for suicide, and some AEDs may increase this risk further. However, this should not prevent adequate treatment of epilepsy, but argues for careful psychosocial assessment and close monitoring and follow-up. Assessment of risk factors for suicide should be considered, which include personal or family history of suicidal behavior, mood disorders, hopelessness, substance abuse, social isolation, and access to lethal methods, such as guns. Patients with suicidal ideation should be referred for mental health evaluation; the urgency of this depends on the severity of symptoms. For any patient presenting with suicidal ideation and severe depression, hopelessness, psychosis, and/or poor psychosocial support an emergency evaluation is generally warranted.

There may be an increased relative risk of suicide with some AEDs, but the absolute risk is small given that suicidality is actually not that common. Balancing this risk against the much more likely and immediate risk of untreated epilepsy, it becomes obvious that there is more benefit than harm in the adequate treatment of epilepsy with an AED.

ANTIEPILEPTIC DRUGS IN PSYCHIATRY

AEDs are frequently used in psychiatry, particularly to treat bipolar disorder. In fact, the majority of AED prescriptions (up to about 70%) are written for off-label uses, including psychiatric conditions and pain disorders (8). For patients with epilepsy and a comorbid psychiatric condition, treatment with an anticonvulsant with potentially beneficial psychiatric properties should be considered. On the other hand, attention to the adverse psychotropic effects of AEDs needs to be considered, particularly in more vulnerable patients with personal or family histories of psychiatric disorders. AEDs used in psychiatry are shown in Table 38.3; adverse psychotropic effects are shown in Table 38.4.

Barbiturates

Barbiturates are known to cause sedation, yet also paradoxical irritability and impulsivity in children and the elderly. Barbiturates have also been associated with depression and suicidal ideation in patients with a positive family history of depression. Barbiturates can lead to dependence, abuse, and withdrawal. In the past, barbiturates have been used to treat alcohol and sedative-hypnotic withdrawal, yet because of the risk of respiratory depression, other agents tend to be preferred.

Phenytoin

Phenytoin is another older agent with a negative psychotropic side effect profile; it is associated with sedation, cognitive slowing, psychosis, and encephalopathy. It does not appear to have a beneficial role in psychiatric disorders; small low-quality trials have shown benefit in reducing impulsivity and aggression.

Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines are frequently prescribed for anxiety and insomnia and have a role in the short term and acute treatment of these conditions. However, benzodiazepines lead to sedation, cognitive slowing, amnesia, ataxia, tolerance, and, at times, abuse, thereby limiting their utility. Benzodiazepines may also cause paradoxical irritability and disinhibition in children and the elderly. They are approved for the treatment of panic disorder (alprazolam, lorazepam), generalized anxiety disorder (alprazolam, clonazepam), insomnia (flurazepam, temazepam), and alcohol withdrawal (chlrodiazepoxide, diazepam, oxazepam). Benzodiazepines are also the primary pharmacologic treatment of catatonia and frequently used in combination with antipsychotics to treat agitation.

Carbamazepine and Related Antiepileptic Drugs

Carbamazepine has been used for over 25 years to treat mania in bipolar disorder; the long-acting formulation is now FDA-approved for the treatment of acute mania (8). It also appears to be effective in the maintenance phase of bipolar disorder in that it prevents recurrent mood episodes (8). Oxcarbamezapine has been studied for bipolar disorder and though it has a better tolerability profile, does not appear to be as effective as carbamazepine in mania or bipolar maintenance treatment in most studies. It may be helpful in reducing aggression and impulsivity, but more research is needed. Carbamazepine has also been used to treat impulsivity and aggression in traumatic brain injury and developmental delay; however, there is inadequate evidence to support this use. Carbamazepine has been shown to be an effective treatment for mild-to-moderate alcohol withdrawal, though it is not widely used as a sole agent for this. Carbamazepine does not appear to cause significant psychotropic side effects, except possibly mild cognitive dulling in some patients.