Psychiatry and medicine

Psychiatry, medicine, and mind–body dualism

Epidemiology of psychiatric disorder in medical settings

The presentation of psychiatric disorder in medical settings

Comorbidity: the co-occurrence of psychiatric and medical conditions

Management of psychiatric disorder in the medically ill

Somatic symptoms that are unexplained by somatic pathology

Somatoform and dissociative disorders

Psychiatric services in medical settings

Psychiatric aspects of medical procedures and conditions

Psychiatric aspects of obstetrics and gynaecology

This chapter considers the relevance of psychiatry to the rest of medical practice. It should be read in conjunction with the other chapters in this book, especially Chapters 8 and 13.

Psychiatry, medicine, and mind–body dualism

Patients usually attend their doctors because of symptoms which are causing distress and/or dysfunction—that is, when they have an illness. Medical assessment is directed at making a diagnosis of the illness, and this diagnosis is used to guide the plan of management. The diagnosis is conventionally defined as either medical or psychiatric.

Medical diagnosis

Most medical diagnoses are based on symptoms and physical signs and the results of biological investigations that together indicate the presence of bodily pathology (abnormal structure and/or function), which is referred to as disease. Not all medical diagnoses are arrived at in this way (e.g. migraine), and ultimately a medical diagnosis is a label for a condition that is conventionally treated by medical doctors and listed in classifications of disease such as ICD-10.

Psychiatric diagnosis

Psychiatric diagnosis was discussed in Chapter 2, and the following brief account is intended to remind the reader of that discussion. A psychiatric diagnosis, like a medical one, is essentially a label for a condition that is conventionally treated by doctors, sometimes psychiatrists, but also other practitioners. Psychiatric diagnoses are listed in the classifications of diseases, along with medical diagnoses, but although some have associated physical pathology, many do not. Because they usually lack known pathology, they are generally referred to as disorders rather than diseases.

In the past, psychiatric diagnoses have been regarded as ‘mental’ in nature, in contrast to the ‘physical’ nature of medical diagnoses. This distinction reflects the absence of gross pathology in most psychiatric disorders, and the fact that these conditions usually present with disturbed mental states or behaviour, rather than physical symptoms. Presentations with physical symptoms are considered later in this chapter.

Medicine, psychiatry, and dualism

Underlying this division of illnesses into physical and mental is the assumption that a parallel distinction can be made in healthy people—that there is ‘mind–body dualism’, an idea commonly attributed to the philosopher Descartes. So-called Cartesian dualism has and continues to exert a profound influence on Western medical thinking (Miresco and Kirmayer, 2006). Although this division has some utility, it can also be problematic.

Limitations of dualism

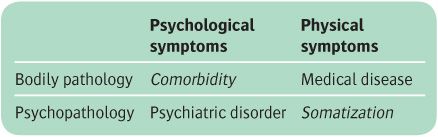

Dualism is at best an oversimplification. It can be convincingly argued that there are no such things as purely physical or psychological conditions, whether in health or illness. The associated assumption that psychological symptoms indicate psychopathology and physical symptoms indicate physical pathology leads to the categories shown in Table 15.1. Two of these, disease and disorder, have been considered. The other two, comorbidity and somatization, will be considered next.

Comorbidity refers to the co-occurrence of two disorders. The term has been extended in the table to describe the co-occurrence of prominent mental symptoms and bodily pathology, as these patients are usually given both a psychiatric and a physical diagnosis (Kisely and Goldberg, 1996). In practice neither of these diagnoses may lead to effective treatment, because a focus on either one of them may lead to neglect of the other. An example is the widespread neglect of depression in patients with medical disease (Moussavi et al., 2007).

Somatization. Some patients have somatic symptoms but no evidence of bodily pathology (DeGucht and Fischler, 2002). It is then unclear whether their illness should be categorized as medical (with presumed but unidentified somatic pathology) or as psychiatric (with assumed psychopathology). In the past these conditions were generally given the medical diagnosis of functional illness (function is abnormal, but there is no pathology). Now these conditions are usually given the psychiatric diagnosis of somatoform disorder. This diagnosis implies first that the somatic symptoms are caused by psychopathology, and secondly that there is a hypothetical process—somatization—by which the psychopathology has caused the bodily symptoms. Such patients can therefore receive both a medical diagnosis (functional disorder) and a psychiatric diagnosis (somatoform disorder), and the resulting confusion and controversy are well illustrated by the literature on the condition known as chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) or myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME) (Sharpe, 2002).

Practical consequences of dualism

One consequence of this way of thinking is the professional and organizational separation of medicine and psychiatry, which in turn contributes to its persistence. This makes it is difficult to provide integrated care for patients with comorbidity and those with somatoform disorders. One organizational response to this problem has been the establishment of liaison psychiatry services to general hospitals (see below).

An integrated approach

New scientific knowledge, such as the demonstration of a neural basis to many psychiatric disorders, has shown that crude dualistic thinking is untenable. Evidence for the effect of psychiatric disorder on the outcome of medical conditions such as myocardial infarction (Meijer et al., 2011) has pointed to the same conclusion. Mind and brain are now increasingly regarded as two sides of the same coin. This paradigm shift implies that psychiatric disorders are no more distinct from medical conditions than the higher nervous system is from the rest of the body (Sharpe and Carson, 2001). Correspondingly, medical care and psychiatric care need to be more integrated (Mayou et al., 2004).

Table 15.1 Traditional ‘dualistic’ categories of mental and physical illness

For the present, dualism continues to shape everyday thinking and practice. Illnesses are given separate medical and psychiatric diagnoses linked to separate knowledge bases and distinct systems of care. The psychiatrist working in medical settings needs to be aware of these problems and help to address them by ensuring that the biological, psychological, and social aspects of illness are considered in every case. This is referred to as the biopsychosocial approach, which was proposed many years ago by Engel (1977) (and which is implicitly if not explicitly adopted throughout this book). The factors that need to be considered in a biopsychosocial formulation are listed in Table 15.2. They can be divided further into predisposing, precipitating and perpetuating causes. The last group of causes is the usual target for treatment, while the first two are relevant to prevention.

Table 15.2 The biopsychosocial formulation

Biological factors Disease Physiology |

Psychological factors Cognition Mood Behaviour |

Social factors Interpersonal Social and occupational Relating to the healthcare system |

Epidemiology of psychiatric disorder in medical settings

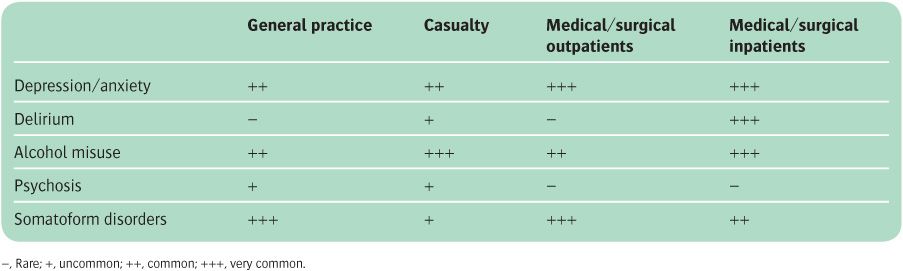

Although psychiatric disorder is common in all settings, the type and presentation of psychiatric disorders differ from one medical setting to another. The most common diagnoses in each setting are shown in Table 15.3.

General practice

The most common psychiatric disorders in general practice are the somatoform disorders, depression, anxiety and stress-related disorders, and substance misuse. Patients with psychosis are uncommon (Ansseau et al., 2004).

Casualty departments

Deliberate self-harm is the major psychiatric problem in casualty departments. Although only a minority of these patients have persistent psychiatric disorders, many have stress-related disorders and some have depressive disorders. Intoxication and delirium related to alcohol and drugs are also common, particularly in inner-city hospitals and among people involved in accidents. Some patients with somatoform disorders and a few with factitious disorders (see p. 391) are frequent attendees at casualty departments (Wooden et al., 2009).

Table 15.3 The relative prevalence of common psychiatric disorders in medical settings other than psychiatry

Medical and surgical outpatient clinics

About one-third of people attending medical and surgical outpatient clinics have a psychiatric disorder (Maiden et al., 2003). Half of these have depressive and anxiety disorders, and most of the remainder have somatoform disorders. In both groups, adequate recognition and treatment of the psychiatric disorder should be an integral part of management, since it has been shown to improve outcome. Depression is a common cause of apparent worsening of a medical condition.

Medical and surgical wards

Around 20% of medical and surgical inpatients have a depressive or anxiety disorder coexisting with their medical disease, 10% have a significant alcohol misuse problem, and 25% of elderly inpatients have an episode of delirium (Saxena and Lawley, 2009). Some patients with severe somatoform disorders undergo multiple investigations and even surgery before the diagnosis is made.

The presentation of psychiatric disorder in medical settings

Although psychiatric disorders commonly present in medical settings with psychological symptoms or behavioural disturbance, other less obvious presentations frequently occur. These are as somatic symptoms, a medical management problem, or an apparent exacerbation of a medical condition.

Psychiatric disorder presenting with somatic symptoms

A significant minority of patients who are seen in general practice and in hospital outpatient clinics have somatic symptoms which cannot be explained by medical disease, and many of these have a psychiatric disorder (Steinbrecher et al., 2011).

Somatic symptoms due to depressive and anxiety disorders. Depression is associated with somatic symptoms, such as fatigue, weight loss, and pain, which may lead to referral to a medical specialty. Anxiety is associated with symptoms of autonomic arousal, such as palpitations, and with breathlessness and sensory symptoms. A World Health Organization collaborative study of patients presenting to primary care in 14 countries found a strong association between somatic symptoms and depressive and anxiety disorders in all centres, despite different cultures and health services. Also, there was a linear relationship between the number of somatic symptoms and the presence of depression and anxiety disorder (Simon et al., 1999). Among the anxiety disorders, panic disorder is an especially important cause of medically unexplained symptoms such as chest pain, dizziness, and tingling (Katon, 1996).

Somatoform disorders. Medically unexplained somatic symptoms in the absence of a depressive or anxiety disorder are diagnosed either as medically unexplained symptoms or alternatively as somatoform disorders. Somatoform disorders are diagnosed when there is a strong suspicion of a psychogenic cause, not just as a diagnosis of exclusion.

Psychiatric disorder presenting as apparent worsening of a medical condition

An exacerbation of complaints about symptoms or disability associated with a chronic medical condition is sometimes caused by a comorbid depressive disorder.

Refusal of treatment is sometimes the first pointer to a psychiatric disorder.

Comorbidity: the co-occurrence of psychiatric and medical conditions

Comorbidity of psychiatric disorders with medical conditions is important. For example, an eating disorder may greatly complicate the treatment of diabetes, and depression is a risk factor for increased mortality and morbidity following myocardial infarction.

Epidemiology

Psychiatric disorder is present in as many as one-third of patients with serious acute, recurrent, or progressive medical conditions. It is difficult to ascertain the exact proportion because standard criteria for the diagnosis of psychiatric disorder include some symptoms that can also be caused by medical illness (e.g. fatigue and poor sleep). Although modifications have been suggested to make the criteria more appropriate for use in individuals with physical as well as psychiatric disorder, none of them are wholly satisfactory. It is best to start with standard criteria and then use knowledge of the medical condition to decide which of the symptoms that point to psychiatric disorder could have originated in this other way. However, this approach requires skilled interviewers and is difficult to achieve on a large scale.

Suicide is easier to identify, and there is an increased risk in the medically ill compared with the general population. Associations have been reported with cancer, multiple sclerosis, and a number of other conditions (Druss and Pincus, 2000).

Common associations between psychiatric and physical illness are shown in Table 15.4. For a review of the epidemiology of psychiatric disorder in association with medical illness, see Mayou and Sharpe (1995).

The importance of psychiatric comorbidity in the medically ill

A comorbid psychiatric disorder can greatly affect the impact and outcome of medical conditions—for example, in patients with ischaemic heart disease (Surtees et al., 2008) and diabetes (Lin et al., 2010). Anxiety and depression are also risk factors for non-compliance with medical treatment (Rieckmann et al., 2006).

Table 15.4 Psychiatric disorders that are common in the medically ill

The causes of psychiatric comorbidity in the medically ill

Psychiatric disorder may be present in medical patients for three main reasons:

1. by chance, as both are common

2. the psychiatric disorder may have caused the medical condition (e.g. alcohol dependence causing cirrhosis of the liver)

3. the medical condition may have caused the psychiatric disorder, either through an action of the disease or its treatment on the brain, or as a reaction to the psychological impact of the medical condition or its treatment, or as a result of the social effects of the medical condition or its treatment (e.g. loss of employment). These factors interact with the person’s premorbid vulnerability.

The medical condition and its treatment

Biological mechanisms

In addition to delirium and dementia, a number of other psychiatric disorders may be caused by the effects of the medical condition on the brain. Conditions that may act in this way include acute infection, endocrine disorders, and some forms of malignancy. This resulting psychiatric condition is referred to in DSM as organic mental disorder. The principal medical conditions that may act in this way are listed in Table 15.5.

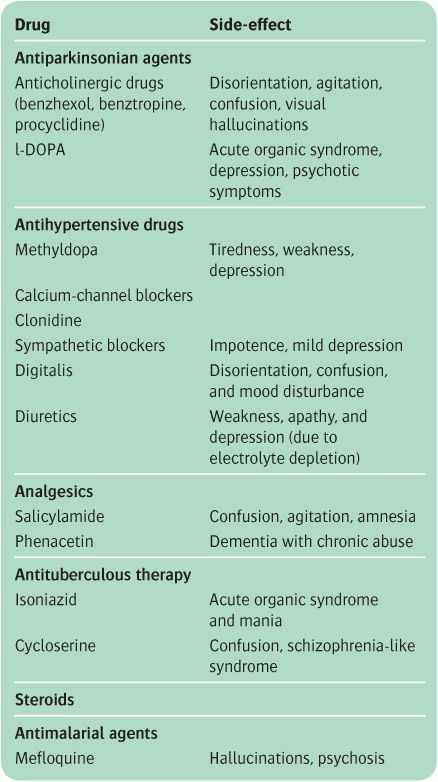

Medical treatment may also cause psychiatric disorder by its effect on the brain. Table 15.6 lists some commonly used drugs that may produce psychiatric disorder as a side-effect. Other treatments associated with psychiatric disorder include radiotherapy, cancer chemotherapy, and mutilating operations such as mastectomy.

Psychological and social mechanisms

The most common means by which a medical condition can cause psychiatric disorder is by its psychological impact. Certain types of medical condition are particularly likely to provoke serious psychiatric consequences. These include life-threatening acute illnesses and recurrent progressive conditions. Psychiatric disorder is more common in chronic medical illness if there are distressing symptoms such as severe pain, persistent vomiting, and severe breathlessness, and when there is severe disability (Katon et al., 2007).

Table 15.5 Medical conditions that may cause psychiatric disorder directly

Depression Carcinoma Infections Neurological disorders (see Chapter 13) Diabetes, thyroid disorder, Addison’s disease Systemic lupus erythematosus |

Anxiety Hyperthyroidism Hyperventilation Phaeochromocytoma Hypoglycaemia Drug withdrawal Some neurological disorders (see Chapter 13) |

Patients at risk for both acute and persistent psychiatric disorder in the course of medical illness include those who:

• have developed psychological problems in relation to stress in the past

• have suffered other recent adverse life events

• are in difficult social circumstances.

The reactions of family, friends, employers, and doctors may affect the psychological impact of a medical condition on a patient. They may reduce this impact by their support, reassurance, and other help, or they may increase it by their excessive caution, contradictory advice, or lack of sympathy.

Prevention of psychiatric disorder in the medically ill

There are three main strategies—first, to identify those at risk, secondly, to minimize the negative effect of illness by providing good medical and nursing care, and thirdly, to detect early and treat effectively the early stages of any psychiatric disorder. Prevention should focus on patients who are suffering illnesses or undergoing treatments which are known to be associated with the development of psychiatric disorder, and on individuals who are psychologically vulnerable as evidenced, for example, by a previous history of psychiatric disorder.

Table 15.6 Some drugs with psychological side-effects

Effectiveness of psychiatric treatments in the medically ill

Clinical experience indicates that psychiatric treatments are generally effective in patients who are also medically ill, although there was limited evidence from randomized controlled trials, because comorbid patients are usually excluded. However, there are now more trials of antidepressants in medically ill patients, and a clearer indication of their value (Taylor et al., 2011). Clinical experience also suggests that psychological treatments such as cognitive–behaviour therapy are effective in medically ill patients, but again there is little evidence from clinical trials. There is better evidence for the benefits of ‘collaborative care’, in which medical treatment and psychiatric treatment are coordinated. This is especially relevant in the management of chronic medical conditions (Katon, 2003), where there is evidence of considerably reduced treatment costs, primarily because of shorter inpatient stays (Koopmans et al., 2005).

Management of psychiatric disorder in the medically ill

Assessment

Assessment is as for psychiatric disorder in other circumstances, but in addition it is necessary to:

• be well informed about the medical condition and its treatment

• distinguish anxiety and depressive disorders from normal emotional responses to physical illness and its treatment. Symptoms that seldom occur in normal distress (e.g. hopelessness, guilt, loss of interest, and severe insomnia) help to make the distinction

• be aware that medical conditions and their treatment may cause symptoms such as fatigue and loss of appetite that are used to diagnose psychiatric disorder

• explore the patient’s understanding and fears of the medical condition and its treatment.

General considerations

The nature of the medical condition and its treatment should be explained clearly and the opportunity provided for the patient to express their worries and fears. The treatment for the associated psychiatric disorder is undertaken using the methods appropriate for the same disorder in a physically healthy person. Careful consideration should be given to possible interactions between the proposed psychiatric treatment and the medical condition and its treatment. Treatment can often be given by the general practitioner or medical specialist, but more complex cases require the skills of a psychiatrist.

Medication

Hypnotic and anxiolytic drugs can provide valuable short-term relief when distress is severe. The indications for antidepressants are the same as those for patients who are not physically ill. The side-effects and possible interactions of the psychotropic drugs with other medication should be considered carefully before prescribing.

Psychological treatments

Explanation and advice are part of the treatment of every patient. Cognitive–behaviour therapy may be chosen in order to reduce distress, increase adherence to treatment, reduce disproportionate disability, and modify lifestyle risk factors.

Somatic symptoms that are unexplained by somatic pathology

Somatic symptoms that are not clearly associated with physical pathology are common in the general population and in patients in all medical settings (Mayou and Farmer, 2002). Although most of these symptoms are transient, a minority are persistent and disabling, and a cause of frequent medical consultations. Some conditions that may give rise to somatic symptoms are shown in Table 15.5.

As noted already, the most common association with psychiatric disorder is with anxiety and depressive disorders, and some conditions meet the criteria for a somato-form disorder (see p. 393). A few of these patients have a factitious disorder, and a very small number are malingering. However, many of those who present to doctors with unexplained somatic symptoms do not meet the diagnostic criteria for any of these conditions. Even in these undiagnosed cases, however, psychological and social factors are often important as causes of the symptoms and as reasons for seeking help, and psychological measures are often helpful.

Terminology

Many terms have been used to describe medically unexplained somatic symptoms, none of which is wholly satisfactory. These terms include hysteria, hypochondriasis, somatization, somatoform symptoms, functional somatic symptoms, and functional overlay. Some of these terms will now be considered further.

• Somatization. This term was introduced at the beginning of the twentieth century by Wilhelm Stekl, a German psychoanalyst, to describe the expression of emotional distress as bodily symptoms. More recently, the term has been used to describe the disorder as well as the process that produces it. Some current usage is even broader, covering the perception of bodily sensations as symptoms and the behaviour of consulting about them. Most usage accepts, explicitly or implicitly, Stekl’s original idea that physical symptoms are an expression of psychopathology—for example, ‘a tendency to experience and communicate psychological distress in the form of somatic symptoms and to seek medical help for them’ (Lipowski, 1988). Some definitions of somatization reject Stekl’s view and use criteria that require physical symptoms to be accompanied by anxiety or mood disorder diagnosed according to standard criteria. Also, current research suggests that emotional distress and somatic symptoms are positively related rather than inversely related as they would be if they were alternative expressions of an underlying psychopathology. Because there is no agreed definition, and because of the unsubstantiated aetiological assumptions, the term ‘somatization’ is unsatisfactory.

• Somatoform disorder. This term was originally used in DSM-III to describe a group of disorders including both traditional psychiatric diagnoses, such as hysteria and hypochondriasis, and newly proposed categories, such as somatization disorder. The somatoform disorders are discussed on pp. 393–401.

• Functional somatic symptoms. This term, which is often used by physicians, refers to a condition caused by a disturbance of bodily function without any known pathology. The term is relatively acceptable to patients, but the use of the word ‘functional’ (as opposed to ‘organic’) has been criticized.

• Medically unexplained symptoms. This term has the advantage of describing a clinical problem without implying any assumptions about its causes. However, it has been criticized as implying that understanding of the condition is not possible. Despite this limitation we use it in this chapter.

Epidemiology

Medically unexplained symptoms are common in the general population and in people attending primary care, and they are more frequent in women than in men (Guthrie, 2008). Although the majority of these symptoms are recognized as not serious, and most of them are short-lived, a sizeable minority lead to distress, functional disability, and role impairment, with more time off work, consulting doctors, and taking medication (Harris et al., 2009).

Aetiology

Although unexplained by any physical pathology, something is known about the causes of medically unexplained symptoms. Most arise from misinterpretation of the significance of normal bodily sensations, which are interpreted as a sign of disease. Concern leads to the focusing of attention on the sensations and this leads to even greater concern, apprehension, and anxiety, which exacerbate and maintain the symptom. For example, awareness of increased heart rate when a person is excited or anxious may lead to worry about heart disease, restriction of daily activities, and repeated requests for investigation and reassurance. Good communication by clinical staff can help to counter the effects of such misinterpretations.

Table 15.7 lists the sources of bodily sensations that may be misinterpreted as symptoms of disease.

Table 15.7 Physiological sources of bodily sensations

Sinus tachycardia and benign minor arrhythmias |

Effects of fatigue |

Hangover |

Effects of overeating |

Effects of prolonged inactivity |

Autonomic effects of anxiety |

Effects of lack of sleep |

Predisposing factors include the following:

• Beliefs about illnesss shape a person’s response to sensations and symptoms. These beliefs may be related to personal experience of illness in earlier life, to involvement in the illness of family or friends, or to portrayals of illness in the media (see Table 15.8).

• Adverse experiences in childhood. Adults with medically unexplained symptoms commonly report adversities in childhood (e.g. poor parenting and various forms of abuse).

• Social circumstances. Medically unexplained symptoms are associated with poor socio-economic circumstances and acute or chronic adversity.

• Personality. Some people with medically unexplained symptoms have had concerns about bodily health going back to adolescence or earlier, and these can be viewed as part of their personality.

Perpetuating factors include the following:

• Behavioural factors, such as repeatedly seeking information about illness, and inactivity.

• Emotional factors, especially chronic anxiety and depression.

• The reactions of others, including doctors as well as family and friends. Doctors may inadvertently prolong the problem by failing to give clear, relevant information that takes into account the patient’s individual fears and other concerns.

For a review of the causes of unexplained symptoms, see Kanaan et al. (2007).

The classification of medically unexplained symptoms

The classification of medically unexplained symptoms has been considered from two perspectives.

1. The medical approach has been to identify patterns of physical symptoms, such as irritable bowel syndrome and fibromyalgia. The syndromes differ somewhat in different countries. For example, low blood pressure syndrome is accepted in Germany, and mal de foie in France, but neither is accepted in England. These are descriptive syndromes, not aetiological entities, and they overlap with other disorders (Wessely et al., 1999). Diagnostic criteria have been produced for some of these syndromes, and these criteria are useful in research and service planning.

2. The psychiatric approach has been to attempt to identify psychiatric syndromes that are the basis of the symptoms. These include anxiety and depressive disorders, somatoform disorder, and factitious disorder. A psychiatric diagnosis and a medical diagnosis can be made in the same patient. For example, a patient with chest pain and no heart disease may receive a medical diagnosis of ‘non-cardiac chest pain’ and a psychiatric diagnosis of ‘panic disorder’, both describing the same symptoms.

Table 15.8 Experiences which may affect the interpretation of bodily sensations

Prevention of medically unexplained symptoms

Until we know more about the causes of medically unexplained symptoms, there is no solid basis for prevention. Although a reduction in predisposing factors in the population, such as childhood abuse and poor parenting, might have some effect, if it was achievable, it is more plausible to address factors such as poor communication by doctors (Ring et al., 2004) and inadequate treatment of depression and anxiety in patients who present with somatic complaints. For a fuller discussion of prevention, see Hotopf (2004).

Treatment of medically unexplained symptoms

There is rather more evidence about the effectiveness of treatments for medically unexplained symptoms. There have been some trials of medication and of cognitive–behaviour therapy, some of which are cited in the course of this chapter.

Antidepressant medication has been shown to benefit several kinds of medically unexplained symptoms, including fibromyalgia and irritable bowel syndrome. Facial pain may be helped by tricyclic antidepressants. This benefit occurs especially (but not exclusively) in patients with marked depressive symptoms (Sumathipala, 2007).

Cognitive–behaviour therapy is moderately effective in the treatment of non-cardiac chest pain, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic fatigue syndrome (Sumathipala et al., 2008).

Management of medically unexplained symptoms

Assessment

An adequate medical assessment is essential. At the end of this the physician should explain:

• the purpose and results of all the investigations that have been carried out, and why it has been concluded that there is no medical cause for the symptoms

• that the symptoms are nevertheless accepted as real, and that it makes sense to look for other causes.

If the patient is then referred to a psychiatrist, the latter should be informed about the results of the investigations, and about the way that these have been explained to the patient.

The psychiatrist explores the nature and significance to the patient of the unexplained symptoms, and completes the usual psychiatric history and a mental state examination, giving particular attention to:

• previous concerns about illness

• current beliefs about illness

• personality

• social and psychological problems

• detection of a depressive or anxiety disorder.

Information should be sought from other informants as well as from the patient.

Management

The basic plan of management is the same for all medically unexplained symptoms, but individual treatment plans should take account of the patient’s special concerns, the type of unexplained symptoms, and any associated psychiatric disorder.

The management of chronic fatigue syndrome and some other special functional medical syndromes is discussed below. The management of somatoform disorders is described later in the chapter.

After the basic procedures outlined in Box 15.1 have been completed, many patients will be reassured. Those who are not may seek repeated investigation and reassurance. Therefore, when all of the medically necessary investigations have been completed, the clinician should explain thoroughly why no further investigation is required. After these initial discussions, it is seldom helpful to engage in repeated arguments about the causes. Most patients are willing to accept at least that psychological as well as biological factors may influence their symptoms, and this acceptance can provide a basis for psychological management.

If the problem is of recent onset, explanation and reassurance are often sufficient. However, if the symptoms have been present for longer, reassurance is seldom enough, and repeated reassurance may lead to increasing requests for yet more removal of doubts. Keeping a diary to explore the relationship of symptoms to psychosocial causes can be more convincing than providing further explanation.

Further treatment should be based on the formulation of the patient’s individual problems. The treatment plan might include, for example, antidepressant medication, anxiety management, and cognitive therapy to change the patient’s inaccurate beliefs about the origin and significance of symptoms.

Much can usually be achieved by the primary care team and by the physicians using these basic procedures. However, chronic and recurrent problems may need to be referred to a psychiatrist or clinical psychologist for further treatment of associated psychiatric disorder, possibly involving cognitive therapy or dynamic psychotherapy. The psychiatrist can also help to coordinate any continuing medical care, especially when this involves several specialties and professions.

Prognosis

The prognosis for less complex cases of fairly recent onset is good, but for chronic, multiple, or recurrent conditions it is much less so. For such cases the realistic goal may be to limit disability and requests for unnecessary medical investigation. Doctors need to recognize that they may also contribute to this process. Bensing and Verhaak (2006) have reviewed evidence from studies in primary care which demonstrate that doctors are as active in proposing biological explanations and tests as these patients are in asking for them.

For more detailed information about the management of medically unexplained symptoms, see Morriss and Gask (2009).

Chronic fatigue syndrome

Many terms have been used to describe this syndrome, the most prominent feature of which is chronic disabling fatigue—the terms include postviral fatigue syndrome, neurasthenia, and myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME). The descriptive term chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) is now preferred. The diagnosis requires that the illness must have lasted for least 6 months, and that other causes of fatigue have been excluded (Fukuda et al., 1994).

Chronic fatigue syndrome has a long history. In the nineteenth century the symptoms were diagnosed as neurasthenia (Wessely, 1990), and in ICD-10 the syndrome can still be recorded in this way, an option that is widely chosen in China and some other countries. The diagnostic criteria for chronic fatigue syndrome overlap with those for a number of other psychiatric disorders, including depression, anxiety, somatoform disorders, and fibromyalgia. This syndrome remains a highly controversial disorder with a powerful lobby against any psychiatric interpretation. The persistence of this conflict exemplifies the problems that are encountered when defining these disorders.

Clinical features

The central features are fatigue at rest and prolonged exhaustion after minor physical or mental exertion. These features are accompanied by muscular pains, poor concentration, and other symptoms included in the list in Table 15.9. People with this condition are commonly most concerned to avoid activity. Frustration, depression, and loss of physical fitness are common.

Epidemiology

Surveys of the general population indicate that persistent fatigue is reported by up to 25% of the population at any one time. The complaint is common among people attending primary care and medical outpatient clinics. However, only a small proportion of people who complain of excessive fatigue meet the diagnostic criteria for chronic fatigue syndrome. Estimates of prevalence are around 0.5% of the general population, with a marked (20- to 40-fold) predominance of females (Prins et al., 2006).

Table 15.9 Case definition of chronic fatigue syndrome (Fukuda et al., 1994)

Aetiology

The aetiology of chronic fatigue syndrome is controversial. Suggested factors include the following:

1. Biological causes. Several biological causes have been proposed, including chronic infection, immune dys-function, a muscle disorder, neuroendocrine dysfunction, and ill-defined neurological disorders. There is no convincing evidence for any of these causes, except infection, which may act as a precipitating factor.

2. Psychological and behavioural factors. These appear to be important, especially concerns about the significance of symptoms, the resulting focusing of attention on symptoms, and avoidance of physical, mental, and social activities that worsen them. Many patients are depressed and/or anxious.

3. Social factors. Stress at work is sometimes important. Belief that there must be a physical cause may be influenced by the stigma attached to a psychiatric diagnosis, and by some of the information provided by patient groups and practitioners.

An alternative approach to aetiology is to consider predisposing, precipitating, and perpetuating factors.

• Predisposing factors include a past history of major depressive disorder and perhaps personality characteristics such as perfectionism.

• Precipitating factors include viral infection and life stresses.

• Perpetuating factors may include neuroendocrine dys-function, emotional disorder, attribution of the whole disorder to physical disease, coping by avoidance, chronic personal and social difficulties, and misinformation from the media and other sources.

For further information, see Harvey and Wessely (2009). Chronic fatigue syndrome in children is considered on p. 664.

Course and prognosis

For established cases, the long-term outcome has been considered to be poor. However, it must be remembered that most of the studies of prognosis relate to patients referred to specialist centres, who may have experienced fatigue for a long time before the referral. Furthermore, most of the studies refer to prognosis before modern treatments (see below) were widely used.

Treatment

Many treatments have been suggested, but very few are of proven efficacy. There have been several randomized controlled trials of cognitive–behavioural therapy and of graded exercise regimes which have shown the benefits of these procedures over standard medical care alone, and over relaxation therapy (White et al., 2011).

Management

Assessment

As with all medically unexplained conditions, assessment should exclude treatable medical or psychiatric causes of chronic fatigue. It is important to enquire carefully about depressive symptoms, especially as the patient may not initially reveal them. Although extensive medical investigations are unlikely to be productive, the psychiatrist can usefully collaborate with a physician when assessing these patients. The formulation should refer to any relevant aetiological factors (see above).

Starting treatment

The six basic steps can be summarized as follows.

1. Acknowledge the reality of the patient’s symptoms and the disability associated with them.

2. Provide appropriate information about the nature of the syndrome for the patient and their family.

3. Present the aetiological formulation as a working hypothesis to be tested, not to be argued over.

4. treat identifiable depression and anxiety.

5. Encourage a gradual return to normal functioning by overcoming avoidance and regaining the capacity for physical activity.

6. Provide help with any occupational and other practical problems.

Medication

If there is definite evidence of a depressive disorder, anti-depressant drugs should be prescribed at the usual doses. Clinical experience suggests that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the best tolerated drugs in this context. Antidepressant drugs are also useful for reducing anxiety, improving sleep, and reducing pain. Low-dose tricyclic antidepressants may have a role here.

Psychological treatment

At the simplest level, these include education about the condition, and the correction of misconceptions about cause and treatment. Cognitive–behavioural methods include addressing misconceptions about the nature of the condition and excessive concerns about activity, and encouraging a gradual increase in activity. Associated personal or social difficulties can be addressed using a problem-solving approach.

For reviews of chronic fatigue syndrome, see Afari and Buchwald (2003) and Harvey and Wessely (2009).

Irritable bowel syndrome

Irritable bowel syndrome is characterized by abdominal pain or discomfort, with or without an alteration of bowel habits, that persists for longer than 3 months in the absence of any demonstrable disease.

Epidemiology

The condition occurs in as many as 10% of the general population (Wilson et al., 2004), the majority of whom do not consult a doctor.

Aetiology

The cause of the syndrome is uncertain, although there appears to be a disturbance of bowel function and sensation. Depressive and anxiety disorders are common among people who attend gastroenterology clinics with irritable bowel syndrome, especially among those who fail to respond to treatment.

Treatment

People with mild symptoms usually respond to education, reassurance about the absence of serious pathology, a change in diet and, when required, anti-motility drugs. More severe and chronic symptoms may need additional treatment. Cognitive–behavioural therapy has been shown to be of benefit, as to a lesser extent have tricyclic antidepressant drugs and SSRIs (Rahimi et al., 2008).

For a review of irritable bowel syndrome, see Mayer (2008).

Fibromyalgia

The term fibromyalgia refers to a syndrome of generalized muscle aching, tenderness, stiffness, and fatigue, often accompanied by poor sleep. A physical sign consisting of multiple specific tender points has been described, but it is probably non-specific. Women are affected more than men, and the condition is more common in middle age. The aetiology is uncertain, but there is a marked association with depression and anxiety. Controlled trials have shown the value of antidepressants (Hauser et al., 2009) and of behavioural interventions, especially those that include increased exercise (Sim and Adams, 2002).

For a review of fibromyalgia, see Mease and Choy (2009).

Factitious disorder

DSM-IV defines factitious disorder as the ‘intentional production or feigning of physical or psychological symptoms which can be attributed to a need to assume the sick role.’ The category is divided further into cases with psychological symptoms only, those with physical symptoms only, and those with both. In factitious disorder, symptoms are feigned to enable the person to adopt a sick role and obtain medical care (in malingering, symptoms are feigned to obtain other kinds of advantage; see below). The term Munchausen’s syndrome denotes an extreme form of this disorder (described below).

Epidemiology

The prevalence of factitious disorder is not known with certainty, but it accounts for about 1% of referrals to consultation–liaison services. The disorder usually begins before the age of 30 years. ‘Illness deception’ in physical disorder, covering both factitious disorder and malingering, is considered relatively common, albeit mild, in occupational health services, where one study (Poole, 2010) found it in 8% of consecutive attendees.

Aetiology

The cause is uncertain, in part because many affected individuals give histories that are inaccurate. There is often a history of parental abuse or neglect, or of chronic illness in early life with many encounters with the medical services, sometimes long periods in hospital, and sometimes alleged medical mismanagement. Previous substance misuse, mood disorder, and personality disorder are other common features. Many patients have worked in medically related occupations.

Prognosis

This is variable, but the condition is usually long-lasting. Few patients accept psychological treatment, but some improve during supportive medical care. In some cases there is evidence of other disturbed behaviours, including abuse of children and (on the part of those working in health professions) harm to patients.

Management

Assessment

When factitious disorder is suspected, the available information should be reviewed carefully, including the history given by informants as well as that provided by the patient. A psychiatrist may be able to assist in this assessment, and in cases of doubt further specialist medical investigation may be needed. Additional evidence may be obtained by careful observation of the patient, but the ethical and legal aspects of any proposal to make covert observations should be considered most carefully.

Starting treatment

When the diagnosis has been made, the doctor should explain to the patient the findings and discuss their implications. This should be done in a way that conveys an understanding of the patient’s distress and makes possible a discussion of potential psychosocial causes. Although some patients admit at this point that the symptoms are self-inflicted, others persistently deny this. One should not simply assume in this case that the patient is being deliberately misleading. Examining these patients (as with ‘fabulist’ patients) often yields a sense of self-deception where the process lies somewhere between conscious (fabulist) and unconscious processes. In these cases, management should still be directed to helping the patient to identify and overcome associated psychological and social difficulties, in the hope that improvement in such problems may be followed eventually by a lessening of the factitious disorder.

Staff who had been caring for the patient while the investigations were being performed may become angry when they discover that the patient has deceived them. Such feelings make management more difficult, and the psychiatrist should play a part in resolving them through discussion, and by explaining the nature and severity of the patient’s psychosocial problems. All closely involved staff should be involved in agreeing a treatment plan which defines what future medical care and what help with the associated problems is needed, both for the patient and for the family. Special risks and difficult ethical problems may arise when the patient is a healthcare worker (see Box 15.2).

For a review of factitious disorder, see Bass and Gill (2009).

Munchausen’s syndrome

Richard Asher suggested the term Munchausen’s syndrome for an extreme form of factitious disorder in which patients attend hospital with a false but plausible and often dramatic history that suggests serious acute illness (Asher, 1951). Often the person is found to have attended and deceived the staff of many other hospitals, and to have given a different false name at each of them. Many of these individuals have scars from previous (negative) exploratory operations.

People with this disorder may obstruct efforts to obtain information about them, and some interfere with diagnostic investigations. When further information is obtained, especially that about previous hospital attendance, the patient often leaves. The aetiology and long-term outcome of this puzzling disorder are unknown.

Factitious disorder by proxy

In 1977, Roy Meadow observed two cases of mothers apparently deliberately misleading doctors about their child’s health. He went on to describe a form of child abuse in which parents (or other carers) give false accounts of symptoms in their children, may fake or deliberately induce signs of illness, and seek repeated medical investigations and needless treatment for the children (Meadow, 1985).

The signs most commonly reported are neurological signs, bleeding, and rashes. Some children collude in the production of the symptoms and signs. The perpetrators usually have severe personality disorder, and some have a factitious disorder themselves. Hazards for the children include disruption of education and social development. The prognosis is probably poor for both children and perpetrators, and there is a significant mortality (Sheridan, 2003). Occasional cases of murder of children by professional carers have been described as an extreme form of this disorder; some of these people had factitious disorder (see Box 15.2).

The condition is rare, and diagnosis should be made with great caution and only after the most careful investigation. In the UK, a number of high-profile legal cases have highlighted the danger of diagnosis on insufficient positive evidence and without adequate exclusion of other causes of the child’s symptoms.

Malingering

Malingering is not a medical diagnosis but a description of behaviour. The term denotes the deliberate simulation or exaggeration of symptoms for the purpose of obtaining some gain, such as financial compensation. The distinction from factitious disorder and from somatoform disorder can be difficult, because it requires an accurate understanding of the person’s motives.

Malingering is infrequent, and is most often encountered among prisoners, the military, and people seeking compensation for accidents. Several kinds of clinical picture have been described:

• malingered medical conditions and disability

• malingered psychosis, seen in those who wish to obtain admission to hospital for shelter, or to prolong their stay in hospital, and in criminal defendants who are trying to avoid standing trial or to influence sentencing

• malingered or exaggerated post-traumatic stress disorder

• malingered cognitive deficit.

Ganser’s syndrome (see p. 404) is thought by some to be a form of malingering.

Assessment

Assessment depends on careful history taking and clinical examination, and close observation for discrepancies in the person’s behaviour. Lawyers or insurers sometimes use surveillance by video or other means to detect the behaviour but, for ethical reasons, clinicians seldom do so. Psychological tests have been used to aid detection, but none of these has proven validity.

Management

If malingering is certain, the patient should be informed tactfully and their situation discussed non-judgement-ally. They should be encouraged to deal more appropriately with any problems that led to the behaviour, and in appropriate cases offered some brief face-saving intervention as a way to give up the symptoms.

For a review of malingering, see Eastwood and Bisson (2008).

Somatoform and dissociative disorders

Somatoform and dissociative disorders are considered together in this chapter because they are classified together in DSM-IV. Apart from this, the disorders are not closely linked. Some of the terms used are defined in Box 15.3.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree