Chapter 80 Psychological and Behavioral Treatments for Insomnia II

Implementation and Specific Populations

Intervention Tools

The psychological and behavioral insomnia therapies include a somewhat diverse group of treatments (e.g., relaxation training, stimulus control, cognitive therapy, sleep restriction).1,2 Research and clinical experience with these treatments has produced a number of helpful tools for identifying treatment targets, monitoring adherence and response, and delivering and reinforcing treatment instructions. In this section, we discuss some of the more commonly used clinical tools for implementing these therapies.

Sleep Diaries

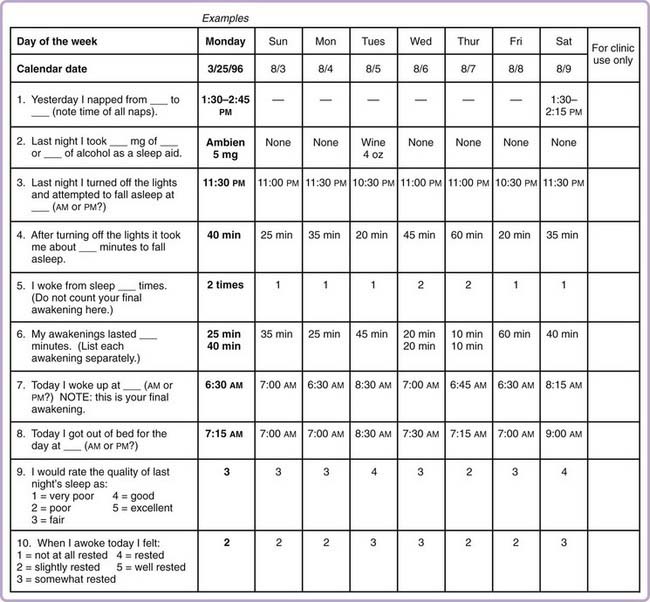

A sleep diary is a standard intervention tool. It provides a daily log or a recording of sleep from the patient’s perspective. Sleep diaries are a mainstay of insomnia assessment and treatment. They quantify the severity of the sleep disorder, help in determining the diagnosis and conceptualizing the case, guide the implementation of behavioral interventions by allowing tracking of progress and adjustment of the behavioral instructions, and reliably measure treatment outcomes.3 They are also useful in identifying problems in adhering to treatment, such as a failure to follow a prescribed sleep schedule.

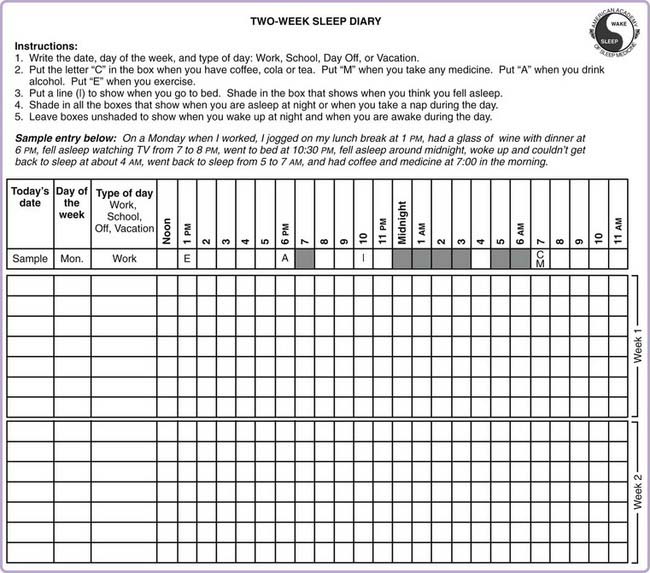

Sleep diaries provide a more accurate and detailed depiction of sleep patterns compared to a patient’s retrospective report.4 They are inexpensive and are as easily administered as a paper questionnaire. There are many published versions available, which differ slightly in the type or amount of information obtained.1,2,4–8 In efforts to standardized insomnia research, recommendations for the type of information obtained from a sleep diary have been proposed.3 At a minimum, these variables include time and duration of naps, bedtime, latency to sleep onset, number of awakenings, wake time during the night, time of final awakening, rise time, total sleep time, sleep efficiency percentage, and sleep quality rating. A traditional sleep diary that meets these standard criteria is presented in Figure 80-1.2

Sleep diaries are available in a number of formats to meet the needs of different populations. For example, The National Sleep Foundation has developed three sleep diary versions geared toward adults, teenagers, and children. The three versions are accessible via the Internet.9 The American Academy of Sleep Medicine also offers a downloadable sleep diary. In this sleep diary, patients are instructed to fill in blocks of time slept (Fig. 80-2).10 This format can provide a richer picture of sleep patterns for patients who have difficulty accurately completing the traditional diary, such as those who have highly erratic sleep patterns or are shift workers.

Figure 80-2 Analog sleep diary offered by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (http://www.sleepeducation.com/pdf/sleepdiary.pdf).

Disadvantages of the traditional paper sleep diary include inaccurate or incomplete patient-recorded values, inability to monitor or confirm daily completion, the clinician’s time required for scoring, and the potential for scoring errors. Newer technologies, such as computerized sleep diaries on hand-held electronic devices and daily patient phone calls to interactive voice recording systems, circumvent many of these disadvantages but are not yet widely available for patient care.11–13 Thus, paper versions of sleep diaries remain the most readily available for assessing insomnia problems, identifying behavioral treatment targets, and tracking treatment responses and adherence.

Actigraphy

Actigraphy is an objective measurement method that assesses limb movement activity via a small recording device typically worn on the wrist (see Chapter 147). Recorded data are subjected to a proprietary algorithm that produces estimates of sleep–wake variables. Current standards of practice outline the primary roles of actigraphy in insomnia as the characterization of circadian or sleep patterns and the evaluation of treatment response.14 Although practice standards for actigraphy recommend a minimum recording period of 72 hours,15 periods of 1 to 2 weeks are preferable.3 It is essential for sleep diaries to accompany actigraphy, so that bed times, rise times, and times the device was removed can be determined. Because actigraphy tends to interpret wakeful stillness in bed as sleep, its validity in insomnia patients is less robust than in sleepers without insomnia.3

Among the many advantages of actigraphy are its unobtrusive nature and ease of use. It can be used in the home environment over extended time periods to capture the night-to-night variability in sleep patterns characteristic of insomnia.15a Because actigraphs record continuously, they provide information on 24-hour rest and activity patterns, allowing unreported daytime sleep episodes to be detected. Actigraphy may also be useful in monitoring adherence to behavioral treatment recommendations and for identifying occasions when violations of those recommendations occur.16 Actigraphy provides streamlined electronic data collection and analysis, a feature that may be of value in clinical and research applications.

Written Behavioral Prescriptions and Instruments for Home Use

The success of behavioral insomnia therapy depends on the patient’s ability to implement therapeutic techniques in the home environment. Patients may be more successful in adhering to behavioral insomnia recommendations if they understand and accept the rationale behind the therapy instructions. This knowledge is particularly salient for treatment recommendations that are counterintuitive, such as directives to limit time in bed and leave the bedroom if not sleeping. Indeed, as has been demonstrated in cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) for depression,17 a patient’s acceptance of the treatment rationale enhances likelihood of a positive treatment outcome. Furthermore, providing a written summary of behavioral prescriptions helps the patient review and remember the information discussed during the therapy session.

Figures 80-3 through 80-5 exemplify handouts that can facilitate the implementation of some behavioral treatments. Of these, sleep restriction and stimulus control are efficacious stand-alone therapies but are more commonly folded into an omnibus multicomponent CBT for insomnia. Discussions of how these various treatment components are used in combination are provided in several available therapist guidebooks.1,2,18,19

Sleep Restriction

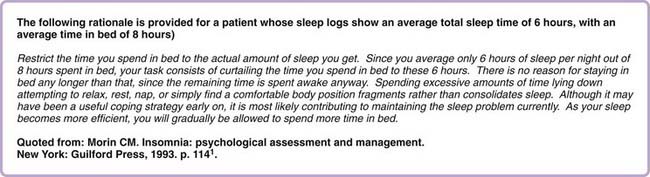

In its original version,20 sleep restriction based the initial time-in-bed prescription on the average total sleep time estimated from 2 weeks of sleep logs. However, 4.5 hours was set as the minimum time in bed. Patients were instructed to go to bed 15 minutes earlier if, after 5 days, sleep efficiency (based on subjective reports) was greater than 90%. If sleep efficiency was less than 85%, time in bed was decreased; no change was made if sleep efficiency fell between 85% and 89%.

Although the general principle of sleep restriction (that of inducing mild sleep deprivation to consolidate sleep and improve sleep efficiency) endures today, many clinicians relax the original sleep restriction protocol in order to promote patient adherence.1,8,21,22 Morin1 provides guidelines for implementing sleep restriction that include flexibility in restricting time in bed to what the patient can tolerate, increasing time in bed (after the initial restriction) at predetermined time intervals rather than in response to sleep efficiency improvements in some clinical situations, adjusting the frequency of time in bed alterations based on patient comfort, giving patients control in selecting bedtime and rising time, and reassuring the patient about the transient side effect of daytime sleepiness. He also provides an excellent description of the therapeutic rationale (see Fig. 80-3). The treatment rationale for sleep restriction is particularly important for patients to understand, because reducing time spent in bed seems counterintuitive and often contradicts strategies they have tried on their own to manage insomnia.

Considering the sleep diary data in Figure 80-1, sleep restriction may be implemented as follows. In this example, the average time in bed is 8.6 hours, and total sleep time is 7 hours. Sleep efficiency is thus calculated as 81.5%. The initial time in bed prescription would be set for 7 hours. The patient would be encouraged to anchor a rise time close to his or her typical rise time, such as 7:00 AM. A recommended bedtime, then, would be set at midnight. This schedule is adjusted as needed based on the therapeutic response over the course of subsequent weeks.

However, insomnia patients as a group tend to underestimate sleep time, although there are admittedly exceptions to this rule.23 Moreover, the sleep-restriction approach outlined here is fairly strict and does not consider normal sleep-onset time or normative amounts of wakefulness during the night. For this reason, it has been suggested2 that it may be reasonable to add 30 minutes to the average sleep time derived from a pretreatment diary to provide a more realistic initial time in bed prescription. Using this more lenient approach, the initial time in bed prescription would be set at 7.5 hours in the above example.

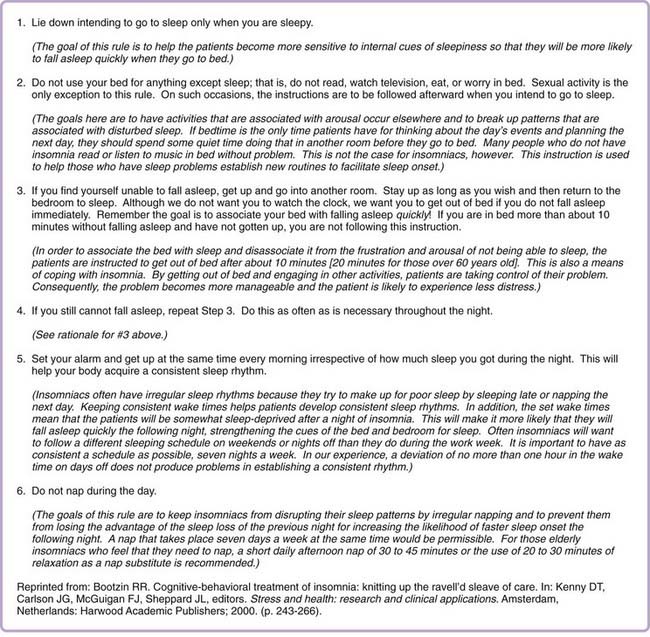

Stimulus Control

The stimulus control instructions originally published by Bootzin in the 1970s essentially have remained unchanged since then.24 The instructions to the patient, along with the rationale for each instruction, are reproduced in Figure 80-4.5 As noted earlier, stimulus control and sleep restriction may be used together in multicomponent insomnia treatments. In such applications it is necessary to slightly alter the stimulus control instruction to go to bed at night when sleepy. This is true particularly when sleepiness occurs too early to allow adherence to the sleep schedule required for sleep restriction. For such instance, patients are told to go to bed when sleepy, but not before the earliest bedtime recommended by the sleep-restriction schedule. Thus, bedtime recommended as part of sleep restriction can be viewed as the earliest allowed bedtime, but the patient could choose to stay up later on a given night when not sufficiently sleepy at that time.

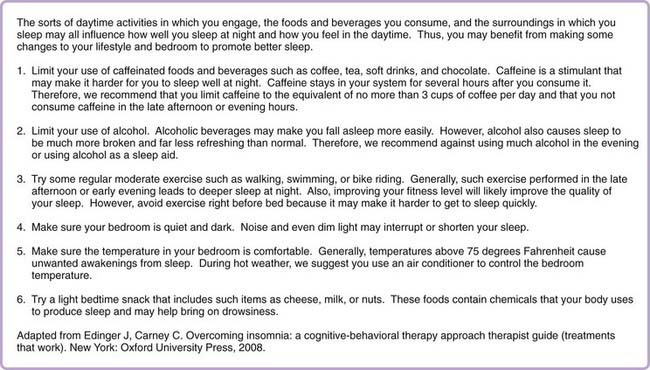

Sleep Hygiene

Sleep hygiene practices are broadly defined and vary among clinicians, but most recommendations cover four core areas: keeping regular bed and rise times, maintaining a comfortable sleep environment, curbing substance use (e.g., alcohol, nicotine, caffeine), and exercising.25 When included as part of a multicomponent treatment package, recommendations about bed and rise times might not be included because they are already subsumed under the stimulus-control and sleep-restriction instructions. A sample sleep hygiene patient handout is presented in Figure 80-5. This handout includes the rationale for each recommendation. Sleep hygiene practices can be assessed with questionnaires such as the Sleep Hygiene Index26 or the Sleep Hygiene Awareness and Practice Scale.27 Riedel28 has developed a sleep hygiene checklist that can be implemented along with a sleep diary to monitor sleep hygiene over time.

Sleep Education

Including a component of sleep education can set the stage for cultivating positive patient expectations and maximizing treatment adherence. Sleep education may include information about normative sleep patterns, circadian functioning, homeostatic sleep drive, the effects of sleep loss, and realistic sleep expectations.2

Additional Educational Resources

Patient-oriented educational resources in the public domain (e.g., websites, pamphlets, self-help books) are widely available at minimal cost and can reinforce or supplement nonpharmacologic insomnia treatments. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine (www.sleepeducation.com), National Sleep Foundation (www.sleepfoundation.org), and American Insomnia Association (www.americaninsomniaassociation.org) are three leading American organizations that disseminate public information regarding insomnia.

Cognitive Therapy Tools

Structured Problem-Solving

Worry or problem-solving in the presleep period is one of the strongest cognitive predictors of delayed sleep onset latency.29 For patients who tend to worry in bed, a variety of intervention strategies have proved useful including relaxation (reviewed in a previous chapter) and techniques more directly focused on sleep-disruptive cognitions.30–33

One of the original problem-solving cognitive strategies is a presleep writing procedure developed by Espie and colleagues32; this technique is similar to a procedure called constructive worry.34 This procedure involves a relatively simple structured problem-solving technique. In constructive worry, patients reporting that worries follow them to bed are asked to set aside some time several hours before bedtime (i.e., usually in the early evening) to complete a homework assignment. The homework is completed using a worksheet that is divided into two columns. The first column is labeled “Concerns” and the second column is labeled “Solutions.” In the Concerns column, patients list worries that have the greatest likelihood of keeping them awake at night. In the Solutions column, patients generate the next, immediate step they can take toward the ultimate goal of solving the problem. Patients are instructed not to write down the ultimate end solution, as they may view this solution as out of reach or difficult to implement. They are refocused on the most immediate step in the sequence. When there are no apparent solutions to solve a problem, patients are encouraged to write down an acceptance-based or self-care strategy. For example, the worry may be that their terminally ill pet will die tonight. This upsetting prospect may have no apparent solution. In such a case, it is helpful to write down plans to implement coping strategies such as calling a friend for moral support.

Worry management techniques are likely most helpful to reduce presleep cognitive arousal and worry, but they have not been shown to produce large improvements in sleep.34 Nonetheless, management of cognitive and emotional complaints is a worthwhile endeavor because patients identify it as one of the most common contributors to insomnia.35

Thought Records

Thought records are a classic cognitive therapy tool for modifying negative thinking.36 Maladaptive thinking styles have been implicated in a variety of disorders including insomnia.30,37–39 The negative sleep-related thoughts and beliefs in insomnia do not appear to be simply attributable to the high rate of comorbid disorders with a similarly unhelpful cognitive style.40 Negative thoughts and moods can exert reciprocal negative influences on each other, and both can perpetuate insomnia. The purpose of the thought record is to observe the connections between negative thoughts and distress and to challenge and interrupt this process.

The observation is achieved via prospective monitoring using a specially designed worksheet divided into columns. Several versions of thought records are available, including a version specifically designed for use with insomnia patients.2 The first three columns of a typical thought record are labeled Situations, Mood and Mood Intensity Rating (0% to 100%), and Thoughts. Observing which situations (column 1) tend to give rise to distress (column 2), and subsequent negative thoughts (column 3) can provide insight into a seemingly automatic cognitive-emotional process. Although observing these connections can be helpful in initiating cognitive change, the main use of the thought record is to actively challenge unhelpful thoughts.

Unhelpful thoughts about sleep are rated as more compelling or more believable by primary30,37–39 and comorbid insomnia groups40 relative to their good-sleeper counterparts. More specifically, people with insomnia have been shown to have cognitions that overestimate the negative effects of insomnia, focus on the belief that sleep is out of one’s control, are rigid or are unrealistic expectations about how much sleep is needed for functioning, and are misconceptions about the causes of insomnia.30,37–39 Whereas some of these beliefs may be true to varying degrees, the cognitive inflexibility or degree to which people with insomnia adhere to such thoughts perpetuate or exacerbate insomnia and are thus unhelpful.

There are very few studies evaluating the relative contribution of cognitive restructuring to CBT for insomnia. A recent pilot study of cognitive therapy produced strong posttreatment effect sizes on daytime and nighttime functioning,41 although these findings can be viewed as preliminary only. Clinical trials testing CBT have shown that CBT produces declines in the belief of unhelpful sleep-related thoughts,30,42 and the posttreatment modification of such maladaptive cognitions relates to other indices of clinical improvement.30,38,42,43 Thus, the sort of cognitive restructuring described is often viewed as a useful component of the overall insomnia treatment process.

Methods of Delivering Treatment

Individualized Treatment

Perhaps the best tested and most commonly used method of delivering psychological or behavioral insomnia therapies has been via individualized treatment consisting of one-on-one sessions between a therapist and single patient. Most published studies that provide descriptions of this form of treatment delivery have employed doctoral-level psychotherapists or psychology graduate students as therapists primarily because the psychological or behavioral insomnia therapies have, for the most part, been developed by psychologists. As suggested by several meta-analyses and systematic reviews, such individualized behavioral insomnia treatment has proven efficacious for short-term and longer-term insomnia management using stand-alone behavioral insomnia therapies (relaxation training, sleep restriction, paradoxical intention, and stimulus control) and multimodal CBT protocols.44–49

Most available descriptions of the multiple-component interventions are derived from clinical trials that outline a fixed treatment package provided on a fixed schedule, usually in four to eight sessions occurring at predetermined intervals. However, in clinical practice, patients’ treatment needs vary, so pretreatment case formulations are typically conducted to decide on the specific treatment components and duration of treatment provided. Although no consensus clinical guidelines exist for matching treatment components to patients, some previous clinic-based studies50,51 describe flexible treatment packages that allow the treatment to be tailored to the patient.

Group Treatment Protocols

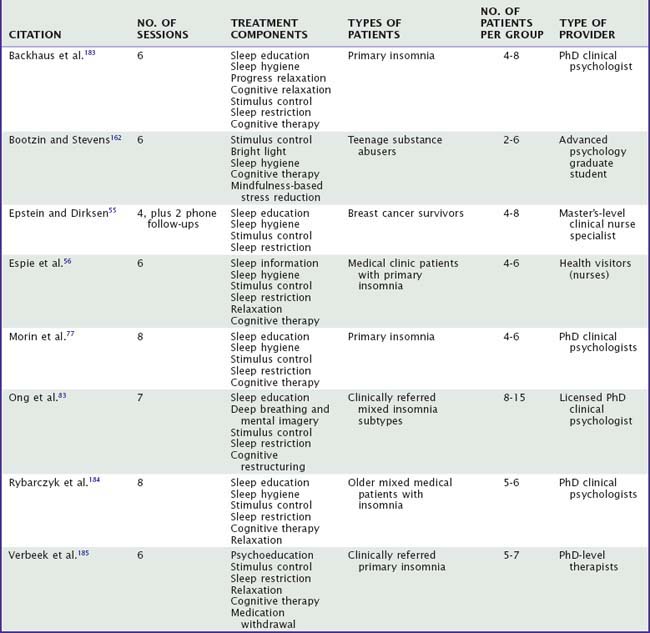

Because providing behavioral insomnia therapy through an individual treatment format is a relatively costly and inefficient form of treatment delivery, various alternate and more cost-efficient delivery methods have been developed. By far the most common alternative delivery format is group therapy. Most previously described group treatment protocols have been CBT or other multicomponent packages that are typically provided in four to eight treatment sessions to a group of patients. Table 80-1 lists and briefly describes a sampling of these group protocols. No one standard brand of group therapy has been employed universally for treating insomnia. However, the descriptions show that group therapy protocols characteristically include an amalgam of such well-established, stand-alone insomnia treatments as stimulus control, relaxation training, and sleep restriction, and these components are often supplemented by sleep education, sleep hygiene instructions, and cognitive therapy. Thus, the group protocols are typically omnibus and include treatment components with well-established efficacy for treating chronic insomnia.

Results of previous meta-analyses44,47 and critical reviews45,46 suggest that group therapy is an efficacious delivery format for behavioral insomnia therapy. Whether group and individual insomnia treatment are equally efficacious is not clear. Some previous meta-analytic results44 suggest a slight superiority of individually administered treatments over group therapy for insomnia treatment. However, conclusions about the relative efficacy of individual and group insomnia treatment based on meta-analyses should be considered cautiously because such conclusions are based on comparisons of studies that employed different therapists, different patient samples, and often different treatment packages. More informative are randomized trials that provide direct comparisons of group and individual therapy within the same study. Studies of this nature have been generally absent from the literature, although one such trial52 showed comparable outcomes for individualized and group CBT for insomnia provided by the same set of therapists. More comparisons of this nature are needed before confident conclusions can be drawn regarding the relative efficacy of these two methods of delivering treatment.

Delivery by Nontraditional Providers

The ranks of sleep specialists who are experts in the behavioral insomnia therapies is currently very limited.53 In efforts to facilitate broad dissemination of behavioral insomnia treatments, some investigators have examined whether nontraditional therapists can effectively deliver these interventions. Because insomnia sufferers typically present first in primary care settings, it seems reasonable to consider using health care professionals (e.g., nurses and family physicians) who are not sleep specialists to provide behavioral interventions. Several studies have demonstrated that various general health care staff including family physicians,54 nurses,55–57 nondoctoral rural mental health clinic staff such as mental health counselors and social workers,58 and primary care counselors59 can effectively administer treatments such as stimulus control and multicomponent CBT in general practice settings. In several of these trials, the nontraditional therapists received training and supervision from an experienced sleep psychologist, so that the therapists employed could be considered specialist provider extenders. This model in which the behavioral sleep medicine specialist assumes a trainer or consultant role might represent a reasonable alternative to higher-priced specialty care and might prove useful for optimal dissemination of the behavioral insomnia therapies in primary care and other traditional medical settings.

Collaboration between a specialist consultant and nonspecialist medical office personnel who deliver treatment has obvious appeal. This delivery model represents an efficient use of behavioral sleep medicine specialists and assures that their expertise is made available, albeit indirectly, in medical settings where most treatment-seeking insomnia patients present for help.60 The training of existing licensed health care personnel to deliver behavioral insomnia therapies also seems reasonable given the relevant training most such professionals have in providing related health care activities. At least one study57 using this delivery method noted treatment effect sizes that fall short of those usually reported for efficacy studies in which more-traditional therapists (psychologists or psychology graduate students) were employed. Whether such differences in treatment outcome are due to “therapist effects” or the presence of more diverse and difficult-to-treat patients encountered in the primary care setting is difficult to determine. Only through future studies that directly compare traditional and nontraditional therapists will this question be answered. When such nonspecialists as family physicians or nurses can be properly trained and given access to a specialist in the behavioral insomnia therapies for consultation, this sort of delivery method seems a reasonable alternative to consider. However, the more difficult and complex insomnia cases seen in such settings might ultimately benefit by more direct contact with behavioral sleep medicine specialists.53

Delivering Treatment Outside of the Office

The various approaches discussed thus far provide a number of delivery methods for disseminating behavioral insomnia treatments. However, these options considered collectively might not meet the needs of all insomnia sufferers. Given the 10% to 15% prevalence61–63 of chronic insomnia in the general population and the limited number of skilled providers, many patients do not have easy access to such treatment. Others with limited financial resources (e.g., the poor and uninsured) might not have sufficient financial resources to seek professional help for their insomnia. Some insomnia sufferers initially prefer to use self-help approaches with limited or no provider contact and thus might resist presenting to clinical settings for insomnia treatment.

Several investigators have tested less expensive treatment delivery methods that can be largely initiated in the home by patients themselves. Mimeault and Morin,64 for example, tested a booklet of self-help CBT instructions, used independently or with therapist guidance provided through phone consultations, against a wait-list control group. Compared to the control condition, those treated with the self-help therapy showed substantially greater sleep improvements, and these improvements were maintained at a 3-month follow-up. The addition of phone consultations with a therapist conferred some advantage over the self-help booklet alone at posttreatment evaluation, but these benefits disappeared by follow-up. In another study, Currie and colleagues65 compared individual behavioral insomnia therapy, treatment with a self-help manual, and a waiting list condition for ameliorating insomnia in a group of recovering alcoholics. Results showed treated patients achieved significantly greater improvements than controls, but no significant differences were noted between the in-person individual therapy and home-administered self-help program. Bastien and coworkers52 found comparable effectiveness of insomnia CBT provided in individual sessions, group meetings, or a self-help format aided by telephone consultation. Rybarczyk’s group66 tested a home-based video CBT program for treating older insomnia patients who had comorbid medical conditions. Whereas this treatment produced greater improvements in sleep and waking functioning than did a wait-list condition, the improvements noted fell short of those achieved with CBT delivered face-to-face in a classroom setting. Considered collectively, these findings suggest that self-administered behavioral insomnia treatments are promising, although contact with a therapist via phone consultation may be needed to improve outcome.

To determine whether behavioral insomnia treatments can be delivered effectively without direct interaction between the patient and a therapist, some investigators have tested treatment protocols provided through mass media dissemination. In perhaps the largest single treatment study to date, Oosterhuis and Klip67 tested a behavioral insomnia therapy provided via a series of eight 15-minute educational programs broadcast on radio and television in the Netherlands. More than 23,000 people ordered the accompanying course material, and data from a random subset of these showed that improvements in sleep and reductions in hypnotic use, medical visits, and physical complaints were achieved among those who took part in this program. However, given the single group nature of their design, it is impossible to discern how these results might compare to more conventional treatments. Three studies68,68a,68b have tested self-help interactive CBT programs delivered to insomnia patients via the Internet. The first of these studies showed little benefit of this approach relative to a no treatment condition, but the latter two studies showed more favorable results for the Internet-delivered intervention. These results collectively suggest that at least some patients benefit by this form of self-help treatment.

Treatment Dosing

In addition to considering the various methods and providers that can be used to deliver the psychological and behavioral insomnia therapies, it is also important to consider what constitutes the proper or optimal dose of such treatments. Previous studies with multiple-component CBT for insomnia have shown efficacy for such interventions delivered in one, two, four, six, and eight individualized sessions and five to eight group sessions. Yet, little is known about how many individual and group sessions are needed on average to achieve optimal treatment outcomes. Despite the ample number of exemplary dose-response studies extant in the pharmacology literature,69 research specifically designed to determine the optimal dosing for any of the psychological and behavioral insomnia therapies has generally been lacking.

The lone exception to this oversight is a recently published study by Edinger and colleagues70 conducted to determine the optimal dosing of their CBT model delivered in an individual therapy format. In this study, patients with primary insomnia were randomly assigned to a no-treatment control (wait-list) or to active treatment comprising one session, two sessions (weeks 1 and 5), four sessions (every other week) or eight (weekly) sessions of CBT delivered over an 8-week period. Results showed that subjective (sleep diary) and objective (actigraphic) sleep measures favored the one- and four-session CBT doses over the other CBT doses and wait-list control. However, comparisons of pretreatment data with data acquired at the 6-month follow-up showed that only the four-session group maintained significant improvements in objective wake time and sleep efficiency measures over time. Moreover, a notably greater percentage of those assigned to the four-session condition achieved more than 50% reduction in the study’s primary sleep outcome measure, subjective wake time after sleep onset, than did those in the other conditions. Considered collectively, this study’s findings imply that for the specific CBT model tested, a dose of four sessions delivered on an every-other-week schedule appears optimal.

In addition to providing one model of ascertaining dose-response curves for behavioral insomnia therapies, this study highlights at least two important dosing factors that can be considered in treatment delivery. The first is the total number of sessions delivered and the second is the interval at which consecutive sessions are scheduled. In the paradigm considered, treatment information and instructions are delivered by an expert therapist, and then the patient implements the strategies learned from the therapist at home and becomes self-sufficient in using them. As suggested in the dosing study,70 the four-session dosing, which provides therapist contact every other week, might offer the patient the optimal balance between therapist guidance and patient independence so self-sufficiency with the treatment strategy is realized. However, the study tested only one of the many available behavioral insomnia treatments and CBT paradigms, so little is currently known about what represents the optimal dosing of the range of individual and group treatments available. A more-recent study71 showed that those with insomnia comorbid to a psychiatric condition had somewhat less impressive treatment outcomes than did primary insomnia patients in response to the four-session CBT model.70 Thus, insomnia diagnosis or comorbidities may be important factors that affect the optimal dosing of psychological and behavioral insomnia therapies.

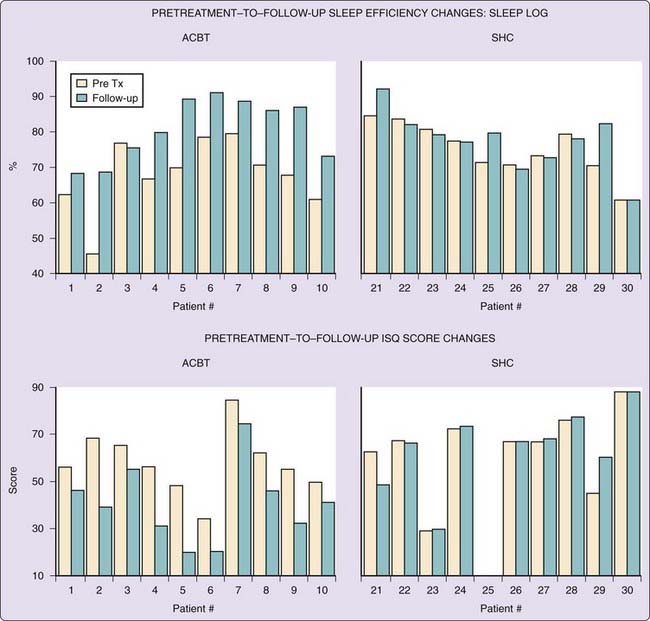

A final consideration pertinent to the discussion of treatment dosing is the observation that some abbreviated interventions are highly effective, at least for those with primary insomnia. Two studies72,73 have tested very similar condensed (two-session) versions of multicomponent behavioral insomnia therapies that included sleep education and modified stimulus control and sleep-restriction strategies. In the former, the condensed CBT proved significantly superior to a sleep hygiene control for improving subjective sleep measures and global insomnia symptoms. Figure 80-6, which shows case-by-case changes in measures of sleep efficiency and insomnia symptoms, exemplifies the study’s findings. In the latter study, Germain and colleagues73 showed that a brief behavioral treatment outperformed a sleep information control therapy across a variety of outcome measures. Figure 80-7, which shows the treatment effect sizes for the brief behavioral therapy relative to a control condition, suggests reasonably impressive outcomes can be achieved with a fairly minimal intervention. Considered together, these studies imply that relatively effective low-dose multicomponent psychological and behavioral insomnia therapies can be developed. Nevertheless, additional studies are needed to determine how these abbreviated treatment models compare to higher doses of the more complex unabridged psychological and behavioral insomnia therapies available.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree