INTRODUCTION

Though the prevalence of anxiety disorders declines with age (a finding consistent with most other mental disorders), anxiety disorders remain the most common psychiatric illness in the elderly1. An estimated 10-20% of older adults experience clinically significant symptoms of anxiety2. Unfortunately, many individuals may never seek treatment, or their anxiety may not be recognized. The result has been a significant under treatment of a very treatable illness.

There are no ‘perfect’ anxiolytic medications for treating the elderly3,4. Medications may vary in effectiveness or have problems with side effects. Further, there are significant gaps in the literature about best treatment practices, which makes evidence-based decisions difficult5. Therefore, we will first review general considerations about treating anxiety in the elderly before reviewing current pharmacological options. Classes of medications rather than specific recommendations for each anxiety disorder will be reviewed since research has not clarified primary treatments for most anxiety disorders in the elderly. Finally, guidelines for the evaluation and selection of pharmacological treatments are suggested.

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS Recognition of Anxiety

Despite the ubiquity of anxiety, either as a disorder or a symptom, recognition is not always apparent. This is especially true in treating the elderly patient. Elders often are less willing to discuss ‘anxiety’, but may report ‘anxiety-equivalent’ symptoms and physical illnesses. Thus a patient may deny feeling ‘anxious’, but admit to feeling ‘jittery’, ‘sick’, ‘uneasy’, ‘flustered’, ‘restless’, ‘ill’, ‘achy’ or ‘bad’. Alternatively, the patient may deny having anxiety, but report having physical symptoms, such as ‘heart pain’, ‘insomnia’ or ‘indigestion’. These complaints may obscure the true diagnosis or complicate another. The physician must therefore be sensitive, not reactive, to the presenting complaint.

Differential Diagnosis

The DSM-IV-TR has identified 12 types of anxiety disorders (Table 100.1). They are based on a cluster of symptoms with a characteristic course and treatment. Anxiety may present as a primary disorder (such as panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder etc.) or as a symptom of another disorder. For example, many common medical disorders (like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, coronary artery disease, early dementia) or common prescription and non-prescription medications (especially caffeine-containing products, cold and flu medications, alcohol or nicotine withdrawal, and certain herbal remedies) may cause anxiety (see Table 100.2). Finally, environmental and social stressors common to late life, such as bereavement, relocation or hospitalization may also cause anxiety. Thus, differentiating the source or sources of anxiety may be difficult.

When to Treat

When considering the treatment of anxiety in older adults, it is important to remember that anxiety is an adaptive emotion that occurs as a normal consequence of stressful experiences6. Stressful life events that frequently occur with age, such as loneliness, fear of isolation, diminished sensory abilities, diminished physical abilities, increased incidence of illness, financial limitations, and the prospect of dying, often generate considerable amounts of anxiety7. While anxiety may be a normal response to life events, it may also become maladaptive, meeting criteria for one of the 12 anxiety disorders. The decision to treat the anxious older patient with medication depends on the severity of the anxiety and the degree to which it interferes with the patient’s functioning8,9. This frequently is seen in decreased coping skills, worsening of cognitive function, exacerbation of physical illnesses, or even a breakdown in support systems10. Therefore, the first task is to assess the impact of the anxiety symptoms on social and emotional functioning or the severity of a co-existing physical illness.

Challenge of Treatment

Research in the treatment of anxiety disorders for elderly patients is limited. A National Institute of Mental Health Workshop on Late-Life Anxiety5 noted three significant research gaps: (i) little consensus on the ‘best’ approach to measure and count anxiety symptoms, syndromes, or disorders in late life; (ii) insufficient numbers of studies that examine anxiety among older adults; and (iii) limited knowledge of the differences in ‘early’ and ‘later’ onset of various anxiety disorders. These limitations become especially significant when making treatment recommendations for elderly anxiety patients. There are very few controlled clinical trials of medication or psychosocial interventions for anxiety disorders in the elderly4. Most recommendations are usually based on case reports or open-label studies in the elderly, or extrapolated from the clinical studies of younger mixed-age adult populations and personal clinical experience. For the most part, there is little reason to doubt the applicability of the studies to the elderly patient, yet the clinician should be aware of the limitations of the research, and sensitive to the developing research in this area.

Table 100.1 DSM-IV anxiety disorders

| Panic disorder without agoraphobia |

| Panic disorder with agoraphobia |

| Agoraphobia without a history of panic disorder |

| Specific phobia |

| Social phobia |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder |

| Acute stress disorder |

| Generalized anxiety disorder |

| Anxiety disorder due to … [a general medical condition] |

| Substance-induced anxiety disorder |

| Anxiety disorder, NOS |

Special Adaptations for the Elderly Patient

Before prescribing anti-anxiety medicines for the elderly, the physician should also be aware of the several age-related physiological changes that may alter drug pharmacokinetics and contribute to increased risk of adverse reactions (see also Chapter 10). These include changes in drug absorption, drug distribution, protein binding, cardiac output, hepatic metabolism and renal clearance11-13. In addition, changes in neurotransmitter and receptor function in the central nervous system (CNS) may make a patient more sensitive to psychotropic drugs14. In general, the usual starting dose of psy- chotropic drugs for elderly patients is roughly one-half of the starting dose for younger adult patients.

Over the past century, a variety of agents have been used for the treatment of anxiety and anxiety disorders, with varying degrees of success. These include antidepressants, antihistamines, antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, beta-blockers and buspirone. Despite the multiple medicines available, Zimmer and Gershon’s (1991) conclusion15 that the ‘ideal geriatric anxiolytic’ has yet to be developed still holds true today. Therefore, effective treatment for excessive anxiety is especially dependent upon a thoughtful, accurate assessment of the patient, as well as a thorough knowledge of the patient’s medication history, medical problems and social support/stress.

Since the 1960s, the benzodiazepines have been the mainstay of drug treatment for patients with situational anxiety, generalized anxiety disorder, and panic disorder16. They are also frequently prescribed for insomnia, relaxation prior to medical procedures, seizure disorders or ‘agitation’. However, in the last two decades, increased attention has been given to the prescription pattern of benzodiazepines in the elderly. In the recent past, benzodiazepines were prescribed at a much higher rate among elderly patients than that of the general population17,18. The percentage of use has declined, especially since the introduction of the SSRIs; however, benzodiazepines remain extensively used in the elderly.

Table 100.2 Medical disorders associated with anxiety as a symptom

| Cardiopulmonary |

| Asthma |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| Hypoxic states |

| Angina pectoris |

| Mitral valve prolapse |

| Cardiac arrhythmias |

| Congestive heart failure |

| Cerebral arteriosclerosis |

| Hypertension |

| Pulmonary embolism |

| Neurologic |

| Partial complex seizures |

| Early dementia |

| Delirium |

| Post-concussion syndrome |

| Cerebral neoplasm |

| Huntington’s disease |

| Multiple sclerosis |

| Vestibular dysfunction |

| Endocrine |

| Carcinoid syndrome |

| Cushing’s syndrome |

| Hypoglycaemia; hyperinsulinism |

| Hypo- or hyperthyroidism |

| Hypo- or hyperparathyroidism |

| Menopause |

| Pheochromocytoma |

| Premenstrual syndrome |

| Medications |

| Anticholinergic medications |

| Caffeine |

| Cocaine |

| Steroids |

| Sympathomimetics |

| Alcohol |

| Narcotics |

| Sedative-hypnotics |

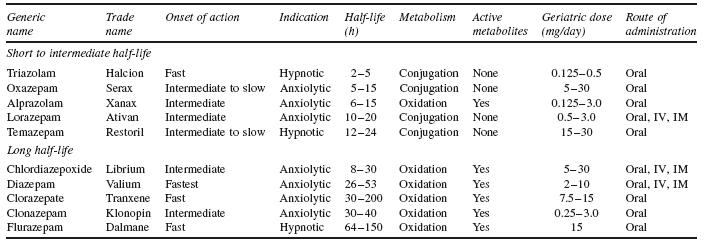

Benzodiazepines are usually classified in two groups based primarily on their length of action: anxiolytics and sedative-hypnotics. Currently, seven benzodiazepines are available for the treatment of anxiety. Listed in their order of introduction, they are chlordiazepox- ide, diazepam, oxazepam, clorazepate, lorazepam, alprazolam and clonazepam19. The most common sedative-hypnotics are triazolam, temazepam and flurazepam. Table 100.3 lists the currently available benzodiazepines and their individual characteristics.

Pharmacokinetics

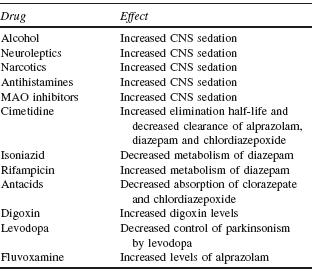

Each benzodiazepine follows one of two biotransformative pathways: oxidation or glucuronide conjugation. Oxidative transformation occurs slowly, contributing to a longer half-life and producing many active metabolites. Conjugative transformation usually occurs

more rapidly and the metabolic products are pharmacologically inactive. As a general rule, benzodiazepines that are inactivated by conjugation are less likely to interact with other medications. For example, cimetidine has been found to inhibit the metabolism of benzodi- azepines that require oxidation, but not benzodiazepines inactivated by conjugation. Table 100.4 lists several important drug interactions with benzodiazepines.

When used for their sedative properties in the elderly, effects of ultra-short, short and intermediate half-life benzodiazepines do not extend to the next day20. Ultra-short benzodiazepines are generally used to treat insomnia rather than daytime anxiety. However, they can cause rebound insomnia after abrupt discontinuation. Safety concerns about triazolam (i.e. after being noted to cause confusion, agitation and hallucinations) have led to its ban in several European countries18. Benzodiazepines with long half-lives can significantly contribute to increased risk of falls and hip fracture in elderly patients21.

Efficacy

Although benzodiazepines have been shown to be effective in younger populations, systematic studies in the elderly are lacking. Benzodiazepines are effective for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). Clonazepam has been shown to be effective for social phobia. Clonazepam and alprazolam are effective in panic disorder. Efficacy and use in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is limited. A paradoxical reaction has been documented when some patients with PTSD are treated with benzodiazepines. None of the benzo- diazepines appear effective for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Of note, though short-term efficacy has been well documented, there are no data on long-term results.

Dependence and Withdrawal

True physiological dependence, resulting in a withdrawal and abstinence syndrome, develops for benzodiazepines usually after three to four months of daily use14

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree