BEHAVIOUR THERAPY AND COGNITIVE BEHAVIOURAL THERAPIES

Behaviour therapy and its related treatments form the largest group of therapies employed in the management of depression. Although their evaluation in older adults is patchy, they offer a number of approaches to helping the depressed older person.

Behaviour Therapy

According to learning theory, depression results from reduced engagement in positively reinforcing behaviours (pleasurable events) and excessive exposure to negative reinforcement (avoidance and negative events)7. Behaviour therapy uses an operant conditioning model to reintroduce positive reinforcement, to reduce the time spent on negative events and to overcome avoidance. This model is presented to the patient as a vicious circle that needs breaking, based on diaries of the patient’s activity and negative mood. This is then followed by scheduling of positively reinforcing behaviours and monitoring of the effect on mood. It may often be possible for patients to resume their previous activities. However, older people experiencing physical illness and disability may be unable to resume all of their previous activities and may need help in identifying alternatives.

Behavioural approaches to depression were later elaborated by incorporating the patterns of negative thinking that occur in depression, giving rise to cognitive behaviour therapy.

Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT)

According to the cognitive model of depression8 an individual’s underlying beliefs about him- or herself and the world may confer a vulnerability to depression that is then triggered in the face of specific types of event. Faulty information processing in the form of over-generalized negative thoughts shapes behaviour and maintains depressed mood.

The validity of the cognitive model as an explanation for cases of depression arising in late life has been questioned given the evidence for structural causes such as cerebrovascular disease. Another limitation of a vulnerability-diathesis model is that an older person may appear to have held the same beliefs for decades and endured previous negative events without developing depression. However, it has been observed in older patients that certain personal beliefs can be adaptive and functional throughout earlier life but can predispose to depression in response to specific age-related events, such as retirement9.

Cognitive behaviour therapy for depression begins with behavioural activation but in contrast with behaviour therapy it includes analysis of the thoughts that underlie inactivity. As the following case example illustrates, negative thoughts are then addressed through direct verbal challenging and testing them out in specific situations (behavioural experiments), supported by written thought diaries.

CBT Case Example: Mrs Jacobs – a woman with physical problems and depressive illness

Mrs Jacobs was a 78-year-old woman referred for therapy by her general practitioner having developed a depressive illness following a stroke. She had been treated with a course of antidepressants, which had brought about a small improvement although she remained significantly depressed with a ‘dread of the future’. She described a loss of confidence and poor concentration and had withdrawn from a number of social activities. She had also noticed a deterioration in her memory, finding it difficult to retain and use new information although this did improve at times when her mood picked up. She had three grown-up children who did not live locally.

Mrs Jacobs had enjoyed a career as a teacher until retiring at the age of 63 years. She had coped with a number of stressful events in her past, such as the loss of her husband, without becoming depressed. Her medical history included hypertension, heart disease and arthritis. Her stroke had occurred after her return from holiday, giving rise to permanent weakness of her right leg. Evaluation by a neurologist, including magnetic resonance imaging, had confirmed the presence of cerebrovas- cular disease. Fearing further strokes, she became anxious that she would not be able to carry on with her interests which included committee work and trips to the theatre. She feared she would be unable to continue living independently and would have to move to a nursing home. Her therapy goals included being able to manage social events and being able to plan realistically for her future.

In session 1 Mrs Jacobs began to recognize the patterns of thoughts and behaviours which were taking place in her depression. She realized that she had become very conscious of the change in her walking which resulted from her weak leg, thinking that other people were noticing it and commenting on it. This added to her anxiety and caused her to avoid social situations or to go to lengths to check that people were not likely to reject her because of it. These observations were included in a simple formulation and this set the scene for a simple diary of these thoughts and behaviours as they occurred at a committee meeting before session 2. She immediately recognized the biased nature of these thoughts, which brought about some improvement in her mood.

In session 2 Mrs Jacobs was helped to notice the link between her mood, energy and activity. At times she was quite tired with her mind ‘in a fog’ which caused difficulty organizing activities such as catching up on tasks at home. This led to self-critical thoughts. She expected herself to function as she had before her stroke, discounting any achievements she was now able to make. She was also disappointed by the day-to-day fluctuations in her energy. To illustrate this process she kept a diary between sessions. She was given written information about the link between activity and depression and was asked to begin activity scheduling. This caused her some difficulty as she aimed to complete the activity schedule perfectly, bringing to attention the high standards she had always set for herself. The exercise also brought to the therapist’s attention the extent to which Mrs Jacobs was struggling with mental tasks because of her cognitive slowing. Mrs Jacobs was encouraged to plan things in advance but to allow some flexibility depending on her physical state and external events. She approached larger commitments by breaking them into smaller stages and using more written records. To support these changes she successfully challenged her self-critical thoughts with responses such as ‘the list of jobs will never finish, so why blame myself?’, ‘is it really important to do it now?’. The beliefs underlying Mrs Jacobs’s high standards were examined – for example, the belief that ‘I must always do everything to the best of my ability’ – and she began to accept that getting older allowed her the opportunity to relax her standards and take some rest.

In session 6, Mrs Jacobs was helped to use thought challenging to deal with her fear of rejection by friends. She found questions such as ‘What am I afraid might happen?’ and ‘Am I exaggerating the importance of events?’ particularly useful. She recognized a tendency to predict that people would not want her. If others were ambiguous in their behaviour (such as not initiating conversation) it was taken as evidence that they did not want her around. She tested out her thoughts using simple behavioural experiments such as initiating conversation with people and being ready to challenge unhelpful thoughts as they arose. She found that actually putting this into practice was not always easy so she needed to plan the stages in some detail beforehand then complete her thought records and observations soon afterwards. She was successful in reducing the intensity of her thought that she was being rejected from 80% to 5%.

By session 9, Mrs Jacobs was becoming more flexible in her activities and coping better with personal relationships. She was still feeling anxious and low in the mornings. She had hopeless thoughts and although she could challenge these successfully later in the morning, she had difficulty doing this at the time. She therefore developed a list of strategies to cope with depression in the morning such as keeping a reminder by her bed of the challenges to unhelpful thoughts and activities she could engage in rather lying in bed ruminating.

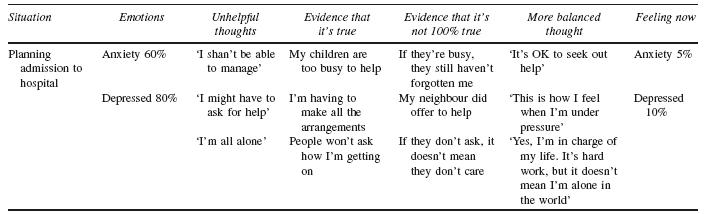

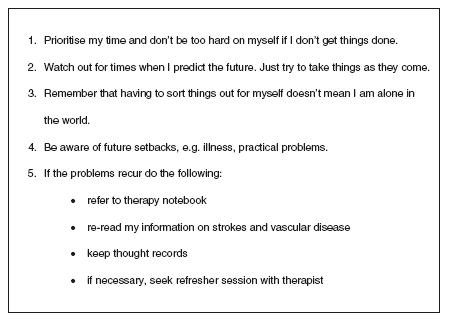

By session 10 Mrs Jacobs’s mood was significantly improved. She still reported mild cognitive deficits such as difficulty naming and slower thinking, related to her cerebrovascular disease. She identified unhelpful thoughts about developing Alzheimer’s disease or losing control of her life. With the therapist she also identified a distortion in her thinking that having irreversible problems (such as her cerebrovascular disease) meant she had an unmanageable problem. Understanding the physical basis to some of her problems also helped her to challenge her self-critical thoughts. At times of additional stress, such as admission to hospital, she would become anxious and depressed and her fears for the future would recur, but she managed to use thought challenging to handle this (Table 87.1). This also helped her to review the plans she had made in case of further disability in the future, such as financial planning and adding her name to the list for her preferred nursing home. At the end of treatment, Mrs Jacobs made a therapy ‘blueprint’ which included a summary of what she had done to achieve her improvement and what she would need to do if her problems recurred (Figure 87.1).

Abridged and reproduced with permission from Wilkinson10, pp. 67-71.

For a detailed description of CBT with older adults, see Laidlaw et al.11

Problem-solving Therapy (PST)

Problem-solving therapy is a brief intervention of six to eight sessions that is usually delivered in primary care; it is designed to help depressed patients to take an active approach to tackling their psychosocial problems. PST can be considered a behavioural intervention in that it tackles the avoidance and reduction in pleasurable activities that occur in depression, and as a cognitive intervention in so far as it addresses the negative perceptions that may interfere with finding practical solutions to problems.

Problem-solving therapy involves the following stages: definition of problems; establishing realistic goals; generating, choosing and implementing solutions; and evaluating outcomes. Use of a therapy manual helps patients to practise these skills and to continue their use after therapy has ended. Clearly, older people often face irreversible obstacles such as bereavement or disability, in which case goal setting is an opportunity to regain some sense of control through tackling the consequences and effects of these problems. For instance, a depressed patient unable to drive after a stroke may identify new ways to travel.

Table 87.1 Mrs Jacobs’s thought diary

Source: Abridged and reproduced with permission from [10], Wilkinson P. (2001) Cognitive behaviour therapy. In: J Hepple, J Pearce & P Wilkinson (Eds), Psychological Therapies with Older People (pp. 61-73). Hove: Bruner-Routledge

Figure 87.1 Extract from Mrs Jacobs’s therapy blueprint

Source: Abridged and reproduced with permission from [10], Wilkinson P. (2001) Cognitive behaviour therapy. In: J Hepple, J Pearce & P Wilkinson (Eds), Psychological Therapies with Older People (pp. 61-73). Hove: Bruner-Routledge

Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT)

Dialectical behaviour therapy has been developed to treat younger adults with personality disorder, particularly borderline disorder12. Its underlying theory assumes a biological predisposition to increased emotional sensitivity and impaired emotional regulation. It combines individual therapy to tackle self-defeating behaviours, such as self- harm, with group training in emotional regulation and managing interpersonal relationships; these are backed up by telephone coaching from a therapist. Therapy techniques include the use of metaphor and stories (dialectical strategies) and standard cognitive behavioural strategies.

The study of personality and personality disorder in old age is in its infancy and is hampered by a lack of robust longitudinal research13. However, there are indications that certain personality traits in older people are associated with recurrent depressive disorder and this has led to the modification of DBT for the treatment of older patients14. Self-defeating patterns of behaviour exhibited by older patients and targeted in DBT may include repeated disengagement from treatment.

For a fuller description of DBT with older adults see Cheavens and Lynch15.

Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT)

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy is used to prevent recurrence of depression. It is derived from both CBT and mindfulness-based stress reduction, an intervention originally developed to reduce distress in patients experiencing chronic pain and illness16. Rather than examine the content of thoughts, as in conventional CBT, MBCT teaches patients how to disengage from recurrent patterns of negative thinking by the use of meditation and refocusing on bodily sensations, particularly breathing. Techniques are taught in group classes with the intention that participants will continue to practise meditation and to employ modified techniques in everyday life. As MBCT aims to prevent rumination over insoluble problems, such as ill-health, it has obvious potential in the treatment of older people. Experience suggests that older patients value its educational approach17.

Efficacy of Cognitive Behavioural Interventions

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree