INTRODUCTION

The maintenance of physical and cognitive functioning and the avoid ance of disease are associated with well-being and quality of life (QoL) in old age, as poor health can lead to loss of control, autonomy and independence1,2. Traditionally, outcomes of treatment have been evaluated in terms of mortality or symptoms, but a more important outcome measure may be the patient’s perspective, as symptoms may improve in one area while overall quality of life decreases because of the negative effects of treatment3. The emergence of QoL as a fundamental measure for evaluating and monitoring health outcomes in old age is attributed to the ethical and economic concerns asso ciated with the ageing population and the concomitant increase in chronic illness and disability. Birren and Dieckmann4 identify three main areas of concern associated with this increase: (i) the impact on health service resources and the potential financial burden antic ipated; (ii) the intrusive use of medical technologies; and (iii) the QoL for people in institutions. In chronic illness, people can suffer from both the disability and the treatment5. Moreover, treatment can often result in limited gains in terms of survival, or absence of cure, which changes the balance as to acceptable side effects. Aggressive interventions may have therapeutic benefits that are overshadowed by the negative effects, thus leading to reduced QoL overall. Any detri mental impact on QoL needs to be weighed against the advantages offered through treatment6. It is the individual’s perception that pre dicts whether they seek help, accept treatment or regard themselves to be well and recovered, and therefore, should be part of any out come measures7. Thus, subjective health measures can be used to help provide a fuller picture of the individual’s health state.

The term quality of life is used frequently in everyday life, with most people assuming they know what it means without considering how to define or measure it. In terms of health, QoL has become a popular, broadly used expression that is frequently taken for granted without the meaning being clear. There is debate about the true def inition and meaning of QoL, particularly whether ratings should be objective or subjective, what criteria should be used and what is actually being measured, ‘the quality of an individual’s life, state of life, or the meaning of life in general’8. QoL is argued to be less related to basic needs than to individual expectations and expe riences of life, which include individual perceptions of well-being, happiness, goodness and satisfaction with various aspects of their lives and environment9-11. What is apparent is that QoL is a multi dimensional concept ‘just as is life itself’12. A wide range of domains is suggested for inclusion as QoL indicators, including physical and mental health, intellectual and emotional function, social and role function, activities of daily living, economic aspects, and job and life satisfaction13-15. The expression QoL may also overlap with the terms ‘health status’ and ‘functional status’, and have been consid ered interchangeable16. Perceptions of well-being may, however, be influenced by psychological factors unrelated to health or function17.

DEFINITIONS AND CONCEPTUALIZATIONS OF QoL

There are several meanings of the term QoL, which remains a vague, elusive concept for which there is no single widely accepted defini tion. The definitions provided are broad and varied; indeed, there may be as many QoL definitions as there are people18. QoL is viewed as ‘a concept which incorporates all aspects of an individual’s existence’19 and as ‘an abstraction which integrates and summarizes all those fea tures of our lives that we find more or less desirable and satisfying’20. The inclusion of the terms life satisfaction, morale and happiness are debated but may be considered to be transient states which should be distinguished from QoL as they differ in their degree of subjectivity21. Alternatively, life satisfaction, self-esteem and phys ical health are argued to be key dimensions of QoL22. Lawton23 defines QoL as ‘the multidimensional evaluation, by both intrap ersonal and social-normative criteria, of the person-environment system of an individual in time past, current and anticipated’ and hypothesizes four dimensions of QoL: behavioural competence, per ceived QoL, objective environment, and psychological well-being. Each sector is intrinsic and considered core to the concept of QoL and also interlinked. Fundamentally, QoL is perceived as being con tinuous and dynamic in nature and may be evaluated negatively or positively depending on the individual’s own internal perceptions and response to their environment.

Within the context of health, QoL is defined as a reflection of patients’ perception and response to their health status and to other non-medical aspects that have an impact on patients’ lives, and within health-related quality of life (HRQoL) this includes physical, psychological and social perspectives24,25. This definition is in keeping with that given by the World Health Organization Quality of Life Group (WHOQOL), as ‘the individuals’ perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns’26. This broad description encompasses the complex nature of the person’s physical, psychological and social well-being in relation to their environment. The recognition of cultural factors is particularly important when considering the QoL of the ageing population and especially those people with dementia. Memory impairment is not regarded as so important in all cultures27. Similarly, functional disability may seem less important in cultural contexts where independence and autonomy in activities of daily living are a less central part of the older person’s role28. Older people are frequently marginalized as society holds a negative view of their QoL, and health and social research tends to focus on decline and disability29. There are, however, both positive and negative elements that impact on an older person’s QoL, and Hughes30 identifies the key domains that should be evaluated when measuring older people’s QoL. These include physical environment, social environment, socioeconomic, cultural and health status, personality and personal autonomy factors.

Lerner31 argues that ‘health is more than just a biomedical phe nomenon; it involves a social human-being functioning in a social environment with social roles they need to fulfil’. The use of QoL as an outcome measure focuses the impact of the patient’s condition and treatment on their emotional and physical functioning and lifestyle3. Hence, health-related QoL has become important in measuring the impact of chronic disease16. This is of particular significance as patients with the same clinical symptoms often differ in their eval uation of what the illness means to their life. The term ‘disability paradox’ is used to describe how patients with significant health and functional problems frequently have high QoL scores despite their health status32. QoL measures can be used to evaluate human and financial costs-benefits of interventions and care provided through assessing change in physical, functional, mental and social health33.

Calman34 suggests that people perceive QoL in relationship to their past experiences, current lifestyle, hopes and ambitions for the future. QoL measures the gap between the individual’s present expe rience and their expectations for the future. QoL can therefore be improved by narrowing this gap, either by improving experience or lowering expectations34. Importantly, the model recognizes the highly individual nature of QoL and the influence of culture and past experience35. Carr et al.36 further propose a model of the relation between expectations and experience and identify three areas of dif ficulty in measuring QoL: people have different expectations; people are at different stages of their illness when QoL is measured; and expectations may change over time. By providing health education, information and increasing awareness of risks, patients are helped to adapt to their disability through changing their health expectations. The impact of the disability on their QoL may thus be reduced36.

SUBJECTIVE AND OBJECTIVE DIMENSIONS OF QoL

Testa and Simonson33 recommend that measures of QoL should cover the objective and subjective components important to the rel evant patient group that may be affected positively or negatively

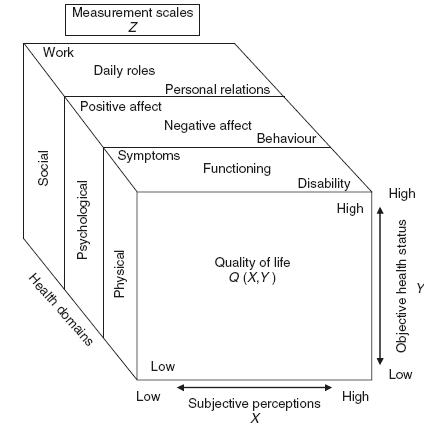

Figure 35.1 Conceptual scheme of the domains and variables involved in a QoL assessment

Source: Reproduced with permission from Testa & Simonson (1996), New England Journal of Medicine, 334: 834-840. Copyright ©1996 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

by interventions. Objective factors are primarily needs based and incorporate basic needs that determine people’s well-being in soci ety, such as environment and material resources, including levels of income, crime, pollution, transport, housing type, access to amenities and employment2,37. Subjective factors include life satisfaction and psychological well-being, morale, individual fulfilment, happiness and self-esteem, and are expressed in terms of satisfaction, values and perceptions of individual life circumstances1. While health sta tus is defined through the objective components, QoL is determined through subjective perception and expectations (Figure 35.1)33. The subjective perceptions thus translate that objective assessment into the actual QoL experienced.33 Nevertheless, Bowling3 cautions that subjective measures are not designed to be used as substitutes for tra ditional measures of clinical endpoints but to complement existing measures and provide a fuller picture of health state.

Variation among QoL scales is often due to the different emphasis placed on objective and subjective dimensions, which domains are covered and the question format rather than differences in how QoL is defined33. The overall satisfaction an individual has with life is argued to be the most important domain of QoL2,38. This means the importance of the individual’s personal sense of satisfaction with various areas of life is recognized; these include physical comfort, emotional well-being and interpersonal connections38.

QoL scales should be able to demonstrate validity but this is com plicated as there is no measure of criterion validity: no scale can provide a full picture of people’s life quality or be relevant to all individuals33,39,40. Content validity includes evaluation in terms of the applicability of the questionnaire and its comprehensiveness, as well as its clarity, simplicity and likelihood of bias41. Scales should also have predictive validity, sensitivity and be responsive to change in QoL, particularly for clinically important changes3,33,42,43. This ensures the areas relevant to the patient’s QoL are measured and that scales are responsive to the different stages of the disease and interventions or treatment given. Orley et al.44 argue that QoL is influenced by a broad range of facets and is therefore unlikely to alter markedly from day to day. Fallowfield45 recommends that QoL measures should discriminate between patient groups and identify those patients experiencing good QoL and those who are not. In addition’ QoL measures used in clinical practice must be appropriate and acceptable for their intended use and the results meaningful and amenable to clinical interpretation43.

GENERIC VERSUS DISEASE-SPECIFIC MEASURES OF QoL

Generic as opposed to disease-specific instruments offer broader measures of health status and are useful for making comparisons with other conditions’ while disease-specific instruments are used for assessing disease-related attributes when greater sensitivity to specific aspects of the clinical condition is required3,33. Generic mea sures include single indicators’ health profiles and utility measures. Health profiles attempt to measure all aspects of health-related QoL potentially affected by a condition or its treatment. Thus generic instruments tend to be lengthy to ensure sensitivity and adequate psychometric properties3. They can be applied irrespective of the underlying condition but may be unresponsive to changes in specific conditions. Disease-specific instruments aim to have greater discrim ination between severity levels of a particular disease and thus have increased sensitivity to clinical outcomes44. They are more concise and should be able to reflect clinically significant change in health status or disease severity. Therefore in order to detect significant clin ical changes’ generic measures may need to be supplemented with disease-specific measures16, particularly for evaluating therapeutic interventions within clinical trials33. The use of disease-specific mea sures may’ however’ be limited as their narrow focus may not assess the impact of disease or interventions upon wider aspects of life’ which could disadvantage arguments for additional resources24,46.

Essentially the use of both generic and disease-specific measures is recommended to ensure assessment of both disease-specific and wider aspects of life and to detect positive or negative impacts of interventions3,16,24.

Self-Assessment Scales

The use of visual analogue scales is a common method for mea suring subjective experiences such as QoL47. They are’ however’ time consuming to complete and may not be relevant to the experi ence being considered45. Self-reports are obtained using standardized measures that have response formats with closed questions in a categorical dichotomous format (e.g. yes/no) or sequences of cat egorized responses (e.g. strongly agree, agree, disagree, strongly disagree). Standardized measures have fixed questions and a range of answers; Carr and Higginson32 caution that these may not measure patients’ QoL unless scores are weighted for the individual patient. Individual weightings are important for obtaining a true assessment of QoL and being responsive to change. Scores may be calculated for each domain separately or combined to provide a composite or index score of overall life satisfaction. The disadvantage of scales that are calculated to produce an overall score is that the total may result from several combinations of responses, thus leading to a loss of information about the individual components of the scale48. Muldoon et al.11 and Lawton49 both argue that the use of a composite score fails to recognize QoL measures as being multidimensional and that it is illogical to aggregate scores that combine appraisals of objective measures of behaviour, function and subjective wellbeing; and there is a need to evaluate individual domains separately within research and clinical practice12,30,49. Alternatively, Gill and Feinstein25 advocate the use of a global rating through aggregating the scores of individual QoL domains as this explains QoL more com prehensively, and they encourage more explicit criteria or weighting of the different components that construct QoL. Furthermore global ratings have been considered more acceptable for use in clinical trials as change in QoL could be more easily distinguished.

Where self-ratings of QoL are difficult to elicit, such as in demen tia, observational ratings may be of more benefit50-52. Observational methods are undertaken either through direct observation of the per son with dementia, which records the frequency at which certain behaviours present, or by applying attribute ratings of observed affect states over time. Direct observation is time consuming and costly but, it has been argued, provides the most objective method of rat ing QoL in dementia as the subjective component is removed49,53

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree