Reactions to stressful experiences

The response to stressful events

Classification of reactions to stressful events

Acute stress reaction and acute stress disorder

Post-traumatic stress disorder

Response to special kinds of severe stress

Introduction

Stressful events frequently provoke psychiatric disorders. Such events can also provoke emotional reactions that are distressing, but not of the nature or severity required for the diagnosis of an anxiety disorder or a mood disorder. These less severe reactions are discussed in this chapter together with post-traumatic stress disorder, which is an intense and prolonged reaction to a severe stressor. With the exception of normal grief reactions, the conditions described in this chapter are listed as disorders in ICD-10 and DSM-IV.

The chapter begins with a description of the various components of the response to stressful events, including coping strategies and mechanisms of defence. The classification of reactions to stressful experience is discussed next. The various syndromes are then described, including acute stress reactions, post-traumatic stress disorder, special forms of response to severe stress, and adjustment disorders. The chapter ends with an account of special forms of adjustment reaction, including adjustment to bereavement (grief) and to terminal illness, and the problems of adults who experienced sexual abuse in childhood.

The response to stressful events

The response to stressful events has three components:

1. an emotional response, with somatic accompaniments

2. a coping strategy

3. a defence mechanism.

Coping strategies and defence mechanisms are overlapping concepts, but they originated from different schools of thought, and for this reason they are described separately in the following account. Individuals have to adapt to stresses, whether they are trying to make sense of specific one-off events, or facing ongoing difficulties that require a change of expectations. The process of coming to terms with stresses is often referred to as ‘working through’ them. This term originated in psychoanalysis to designate the subconscious processing or ‘work’ that was necessary for change. It is now used to mean any coming to terms with emotional difficulties that involves reflection and re-evaluation.

Emotional and somatic responses

These responses are of two kinds:

1. anxiety responses, with autonomic arousal leading to apprehension, irritability, tachycardia, increased muscle tension, and dry mouth

2. depressive responses, with pessimistic thinking and reduced physical activity.

Anxiety responses are generally associated with events that pose a threat, whereas depressive responses are usually associated with events that involve separation or loss. These features of these responses are similar to, but less intense than, the symptoms of anxiety and depressive disorders (described in Chapters 9 and 10, respectively).

Coping strategies

Coping strategies serve to reduce the impact of stressful events, thus attenuating the emotional and somatic responses and making it more possible to maintain normal performance at the time (although not always in the longer term; see below). The term coping strategy is derived from research in social psychology; it is applied to activities of which the person is aware—for example, deliberately avoiding further stressors. (Responses of which the person is unaware are called defence mechanisms; see below.)

Coping strategies are of two kinds: problem-solving strategies, which can be used to make adverse circumstances less stressful, and emotion-reducing strategies, which alleviate the emotional response to the stressors.

Problem-solving strategies include:

• seeking help from another person

• obtaining information or advice that would help to solve the problem

• solving problems—making and implementing plans to deal with the problem

• confrontation—defending one’s rights, and persuading other people to change their behaviour.

Emotion-reducing strategies include:

• ventilation of emotion—talking to another person and expressing emotion

• evaluation of the problem—to assess what can be changed and try to change it (by problem solving), and what cannot be changed and try to accept it

• positive reappraisal of the problem—recognizing that it has led to some good (e.g. that the loss of a job is an opportunity to find a more satisfying occupation)

• avoidance of the problem—by refusing to think about it, avoiding people who are causing it, or avoiding reminders of it.

Coping strategies are generally useful for reducing the problem or lessening the emotional reaction to it. However, they are not always adaptive. For example, avoidance may not be adaptive in the early stages of physical illness, because it can lead to delay in seeking appropriate treatment. Therefore a person needs not only the ability to use coping strategies, but also the ability to judge which strategy should be used in particular circumstances.

Maladaptive coping strategies

These strategies reduce the emotional response to stressful circumstances in the short term, but lead to greater difficulties in the long term. Maladaptive coping strategies include the following:

• use of alcohol or unprescribed drugs to reduce the emotional response or to reduce awareness of stressful circumstances

• deliberate self-harm either by drug overdose or by self-injury. Some people gain relief from tension by cutting their skin with a sharp instrument to induce pain and draw blood. Others take overdoses to withdraw from the situation or to show their need for help

• unrestrained display of feelings can reduce tension, and in some societies such behaviour is sanctioned in particular circumstances (e.g. grieving). In other circumstances, such behaviour can damage relationships with people who would otherwise have been supportive

• aggressive behaviour—aggression provides immediate release of feelings of anger. In the longer term, it may increase the person’s difficulties by damaging relationships.

Coping styles

When particular coping mechanisms are used repeatedly by the same person in different situations, they are said to constitute a coping style. Some people change their coping strategies according to the circumstances—for example, they may use problem-solving strategies at work but employ avoidance when unwell. Some people habitually use maladaptive strategies—for example, they repeatedly abuse alcohol or take overdoses of drugs when under stress. More recent research has distinguished between coping style, which is seen as a relatively enduring behavioural trait, and coping response, which is much more specific to particular stressful environments.

Defence mechanisms

Defence mechanisms (see Box 8.1) are unconscious responses to external stressors as well as to anxiety arising from internal conflict. They were originally described by Sigmund Freud and later elaborated by his daughter, Anna Freud (1936). In response to stressful circumstances, the most frequent defence mechanisms are repression, denial, displacement, projection, and regression. Defence mechanisms are unconscious processes (i.e. people do not use them deliberately and are unaware of their own real motives, although they may become aware of these later through introspection or through another person’s comments). Freud identified defence mechanisms in his study of the ‘psychopathology of everyday life’, a term that he applied to slips of the tongue and lapses of memory. The concept of defence mechanisms has proved useful in understanding many aspects of the day-to-day behaviour of people under stress, notably those with physical or psychiatric illness. Freud also used the concept of mechanisms of defence to explain the aetiology of mental disorders, but this extension of his original observations has not proved useful.

The main mechanisms of defence are described in Box 8.1

Present circumstances, previous experience, and response to stressful events

Brown and Harris (1978) showed that the response to a stressful life event is modified by present circumstances and by past experience. Some current circumstances make a person more vulnerable to stressful life events—for example, the lack of a confidant with whom to share problems. Such circumstances are called vulnerability factors. Previous experience can also increase vulnerability. For example, the experience of losing a parent in childhood may make a person more vulnerable in adult life to stressful events involving loss. It is difficult to examine these more remote associations scientifically.

Classification of reactions to stressful events

Although they are included within the classifications of diseases, not all reactions to stressful events are abnormal. Grief is a normal reaction to the stressful experience of bereavement, and only a minority of people have a very severe or abnormally prolonged reaction. There is also a normal pattern of reaction to a dangerous or traumatic event such as a car accident. Most people have an immediate feeling of great anxiety, are dazed and restless for a few hours afterwards, and then recover; a few people have more severe and prolonged symptoms—an abnormal reaction. It is difficult to decide where to draw the separation between normal and abnormal reactions to stressful events in terms of severity or duration, and in practice the division is arbitrary. Similarly, among patients who are in hospital for medical or surgical treatment, most are anxious but a few are severely anxious and show extreme denial or other defence mechanisms that impair cooperation with treatment.

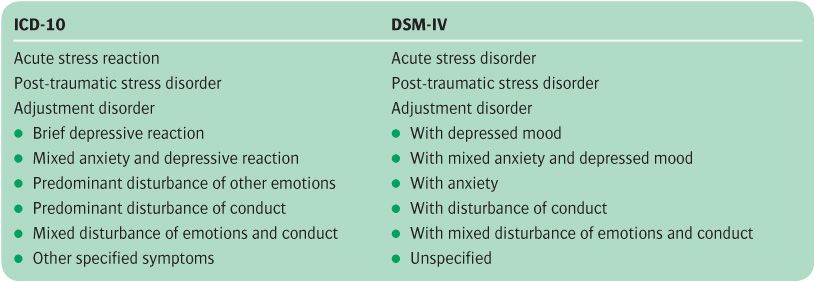

ICD-10 and DSM-IV reactions to stressful experiences are classified into three groups (see Table 8.1).

Acute reactions to stress

This category is for immediate and brief responses to sudden intense stressors in a person who does not have another psychiatric disorder at the time. The ICD-10 definition of acute stress reaction requires that the response should start within 1 hour of exposure to the stressor, and that it begins to diminish after not more than 48 hours. The DSM-IV definition of acute stress disorder states that the onset should occur while or after experiencing the distressing event, and requires that the condition lasts for at least 2 days and for no more than 4 weeks. These two definitions capture different phases of the anxiety response as the different terms, reaction and disorder, suggest. ICD-10 refers to the short-lived normal response, whereas DSM-IV refers to the more prolonged response, which is less common. Both diagnostic systems require that the stressor must be of an exceptional nature and, in the case of DSM-IV, that actual or threatened injury to self or others has occurred.

Table 8.1 Classification of reactions to stressful experience

The order of the subgroups has been changed to show the similarities and differences between the two systems.

Post-traumatic stress disorder

This is a prolonged and abnormal response to exceptionally intense stressful circumstances such as a natural disaster or a sexual or other physical assault.

Adjustment disorder

This is a more gradual and prolonged response to stressful changes in a person’s life. In both ICD-10 and DSM-IV, adjustment disorders are subdivided, according to the predominant symptoms, into depressive, mixed anxiety, and depressive, with disturbance of conduct, and with mixed disturbance of emotions and conduct. DSM-IV has an additional category of ‘adjustment disorder with anxiety.’ ICD-10 has an additional category of ‘predominant disturbance of other emotion’, which includes not only adjustment disorder with anxiety, but also adjustment disorder with anger.

In ICD-10 the three types of reaction to stressful experience are classified together under ‘reactions to stress and adjustment disorders’, which is a subdivision of section F4, ‘neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders.’ The defining characteristics of this group of reactions to stress and of adjustment disorders are as follows:

• They arise as a direct consequence of either acute stress or continued unpleasant circumstances.

• It is judged that the disorder would not have arisen without these factors.

A different organizing principle is used in DSM-IV. Here acute stress disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder are classified as anxiety disorders, while adjustment disorders have their own place in the classification, separate from the anxiety disorders.

Additional codes in ICD-10

If any of these reactions is accompanied by an act of deliberate self-harm, another code can be added to record this fact (codes X60–X82 list 23 methods of self-harm). It is also possible to specify certain kinds of stressful event by adding a code from Chapter Z. For example, Z58 denotes problems related to employment and unemployment, and Z63 denotes problems related to family circumstances.

Coding grief reactions

In ICD-10, abnormal grief reactions are coded as adjustment disorders. Reactions to bereavement that are appropriate to the person’s culture are not included. If it is appropriate to code them as part of the description of the patient’s condition, code Z63.4 (death of a family member) can be used.

Acute stress reaction and acute stress disorder

Clinical picture

The core symptoms of an acute psychological response to stress are anxiety or depression. Anxiety is the response to threatening experiences, and depression is the response to loss. Anxiety and depression often occur together, because stressful events often combine danger and loss—an extreme example is a road accident in which a companion is killed. Other symptoms include feelings of being numb or dazed, difficulty in remembering the whole sequence of the traumatic event, insomnia, restlessness, poor concentration, and physical symptoms of autonomic arousal, especially sweating, palpitations, and tremor. Anger or histrionic behaviour may be part of the response. Occasionally there is a flight reaction—for example, when a driver runs away from the scene of a road accident.

Coping strategies and defence mechanisms are also part of the acute response to stressful events. Avoidance is the most frequent coping strategy, where the person avoids talking or thinking about the stressful events, and avoids reminders of them. The most frequent defence mechanism is denial.

Usually avoidance and denial recede as anxiety diminishes; memories of the events can be more readily accessed and the person is able to think or talk about them with less distress. This sequence allows the person to work through and come to terms with the stressful experience, although there may be continuing difficulty in recalling the details of highly stressful events.

Variations in the clinical picture

Not all responses to acute stress follow this orderly sequence, in which coping strategies and defences are maintained long enough to allow the person to function until anxiety and depression subside, and are then abandoned so that working through can occur. Not all coping strategies are adaptive—an example is the excessive use of alcohol or drugs to reduce distress. Defence mechanisms may also be of a less adaptive type, such as regression or displacement. Sometimes defence mechanisms persist for longer than is adaptive—for example, denial may persist for so long that ‘working through’ is delayed. Sometimes vivid memories of the stressful events intrude into awareness as images and flashbacks or disturbing dreams. When this state persists, the condition is called a post-traumatic stress disorder (see p. 159).

Diagnostic conventions

As noted above, ‘acute stress reaction’ in ICD-10 and ‘acute stress disorder’ in DSM-IV capture different phases of the psychological response to stress (see p. 156). The DSM-IV definition refers to cases of more clinical importance, and it is widely used. People who develop acute stress disorder are more likely to experience subsequent post-traumatic stress disorder (Brewin et al., 2003). Indeed the symptomatology of post-traumatic stress disorder is similar to that of acute stress disorder, the main difference being in the timing and duration of symptoms. However, around 50% of those who eventually develop post-traumatic stress disorder after a trauma do not meet the criteria for acute stress disorder soon after it (McNally et al., 2003).

Both systems of classification describe typical symptoms of the disorder. In DSM-IV the diagnosis of acute stress disorder requires marked symptoms of anxiety or increased arousal, re-experiencing of the event, and three of the following five ‘dissociative’ symptoms:

• a sense of numbing or detachment

• reduced awareness of the surroundings (‘being in a daze’)

• derealization

• depersonalization

• dissociative amnesia.

There must also be avoidance of stimuli that arouse recollections of the trauma, and significant distress or impaired social functioning.

In ICD-10, dissociative and other symptoms are not required to diagnose the disorder in its mild form (F43.00), but two are required for the moderate form (F43.01) and four for the severe form (F43.02), from the following list of seven:

• withdrawal from expected social interaction

• narrowing of attention

• apparent disorientation

• anger and verbal aggression

• despair and hopelessness

• inappropriate or purposeless activity

• uncontrollable and excessive grief.

The terms acute stress reaction and acute stress disorder are used only when the person was free from these symptoms immediately before the impact of the stressful event. Otherwise the response is classified as an exacerbation of pre-existing psychiatric disorder.

Epidemiology

Rates in the population are unknown. The rate of acute stress disorder reported among survivors of motor vehicle accidents is 13% among survivors (Harvey and Bryant, 1998), and among victims of violent crime it is 19% (Brewin et al., 1999). After the Wenchuan earthquake in China, about 30% of the survivors met the DSM-IV criteria for acute stress disorder (Zhao et al., 2008).

Aetiology

Many kinds of event can provoke an acute response to stress—for example, involvement in a significant but brief event (e.g. a motor accident or a fire), an event that involves actual or threatened injury (e.g. a physical assault or rape), or the sudden discovery of serious illness. Some of these stressful events involve life changes to which further adjustment is required (e.g. the serious injury of a close friend involved in the same accident). Not all people who are exposed to the same stressful situation develop the same degree of response. This variation suggests that differences in constitution, previous experience, and coping styles may play a part in aetiology. However, there is little factual information available, as research has focused on the more severe and lasting post-traumatic stress disorder.

Treatment

Planning for disaster

Planning is needed to ensure an immediate and appropriate response to the psychological effects of a major disaster. Such a response can be achieved by enrolling and training helpers who can support victims and are willing to be called on at short notice, and by agreeing procedures for contacting these helpers promptly. At the time of the disaster, priorities have to be decided between the needs of the victims of the disaster, those of relatives (including children), and those of members of the emergency services who may be severely affected by their experiences. The essential elements of psychological assistance for victims of disaster have been described by Alexander (2005) (see Box 8.2).

Debriefing

After a major incident, counselling has often taken the form known as debriefing, or Critical Incident Stress Debriefing (CISD), provided either individually or in a group. In debriefing the victim goes through the following stages after the counsellor has first explained the procedure:

• facts—the victim relates what happened

• thoughts—they describe their thoughts immediately after the incident

• feelings—they recall the emotions associated with the incident

• assessment—they take stock of their responses

• education—the counsellor offers information about stress responses and how to manage them.

Debriefing has been widely used, but current evidence suggests that single-session ‘stand-alone’ debriefing is not helpful in lowering subsequent psychological distress, and might even be harmful (for a meta-analysis, see Rose et al., 2003). The place of psychological interventions in major disasters is not without controversy. Some argue that it can isolate and pathologize the victim, and that energies should be directed towards getting individuals back to their families as soon as possible, and mobilizing normal social support structures (Summerfield, 2006).

Management

After a traumatic event, many people talk informally to a sympathetic relative or friend, or to a member of the professional staff dealing with any physical injuries that originated during the incident. Since in most cases stress reactions will resolve with time, a policy of watchful waiting is appropriate, although it is good practice to offer a follow-up appointment after about 1 month to identify subjects whose stressful symptoms are not settling and who might therefore be at high risk of developing post-traumatic stress disorder.

More formal psychotherapy may be needed if there is no relative, friend, or professional who can assist, if the stressful circumstances cannot easily be discussed with a relative or friend (e.g. in some cases of rape), or if the response is prolonged or severe. The victim can be reassured that the condition is relatively common, and often short-lived. Advice may be needed about ways of dealing with the consequences of the traumatic event. If anxiety is severe, an anxiolytic drug may be prescribed for a day or two, and if sleep is severely disrupted a hypnotic drug may be given for one or two nights. If more formal psychotherapy is needed, there is evidence that brief trauma-focused cognitive–behaviour therapy is more effective than supportive counseling, and may help to prevent the subsequent development of post-traumatic stress disorder (McNally et al., 2003; Roberts, 2009).

Post-traumatic stress disorder

This term denotes an intense, prolonged, and sometimes delayed reaction to an intensely stressful event. The essential features of a post-traumatic stress reaction are as follows:

1. hyperarousal

2. re-experiencing of aspects of the stressful event

3. avoidance of reminders.

Examples of extreme stressors that may cause this disorder are natural disasters such as floods and earthquakes, man-made calamities such as major fires and serious transport accidents, or the circumstances of war, and rape or serious physical assault on the person. The original concept of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was of a reaction to such an extreme stressor that any person would be affected by it. Epidemiological studies have shown that not everyone who is exposed to the same extreme stressor develops PTSD; thus personal predisposition plays a part. In many disasters the victims suffer not only psychological distress but also physical injury, which may increase the likelihood of PTSD. Other predisposing factors are reviewed below in the section on aetiology.

The condition now known as PTSD has been recognized for many years, although under other names. The term PTSD originated during the study of American servicemen returning from the Vietnam War. The diagnosis meant that affected servicemen could be given medical and social help without being diagnosed as suffering from another psychiatric disorder. Similar psychological effects have been reported (under other names) among servicemen in both world wars, and among survivors of peacetime disasters such as the serious fire at the Coconut Grove nightclub in America in 1942 (Adler, 1943). For a historical review of the concept of PTSD, see Jones et al. (2003).

Other reactions to severe stress

PTSD occurs only after exceptionally stressful events, but not every response to such events is PTSD. Six months after a serious accident, major depression may actually be more frequent than PTSD (Kuhn et al., 2006). ICD-10 has a category of ‘Enduring personality changes after catastrophic experience’ (see Box 8.3). This and other conditions may occur instead of, but also as well as, PTSD. For example, of those Vietnam War veterans who met the diagnostic criteria for PTSD, 43% had at least one other diagnosis. The most frequent additional diagnoses were atypical depression, alcohol dependence, anxiety disorder, substance misuse, and somatization disorder (Mac-Farlane, 1985).

Clinical picture of PTSD

The clinical features of PTSD can be divided into three groups (see Table 8.2). The first group of symptoms is related to hyperarousal, and includes persistent anxiety, irritability, insomnia, and poor concentration. The second group of symptoms centres around intrusion, and includes intense intrusive imagery of the events, sudden flashbacks, and recurrent distressing dreams. The third group of symptoms is concerned with avoidance, and includes difficulty in recalling stressful events at will, avoidance of reminders of the events, a feeling of detachment, inability to feel emotion (‘numbing’), and diminished interest in activities. The most characteristic symptoms are flashbacks, nightmares, and intrusive images, sometimes known collectively as re-experiencing symptoms.

Maladaptive coping responses may occur, including persistent aggressive behaviour, the excessive use of alcohol or drugs, and deliberate self-harm and suicide (Ahmed, 2007).

Table 8.2 The principal symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder

Other features

Depressive symptoms are common, and guilt is often experienced by the survivors of a disaster. After some traumatic events, survivors feel forced into a painful reconsideration of their beliefs about the meaning and purpose of life. Dissociative symptoms such as depersonalization are also prominent in some patients (Lanius et al., 2010).

Onset and course

Symptoms of PTSD may begin very soon after the stressful event, or after an interval usually of days, but occasionally of months, although rarely more than 6 months. In DSM-IV, PTSD cannot be diagnosed until at least 1 month of symptomatology has elapsed; until then the condition is regarded as an acute stress disorder. However, in these circumstances it is doubtful whether the diagnosis of stress-related disorder and PTSD represents two separate conditions (Brewin et al., 2003). If the person experiences a new traumatic event, symptoms may return even if the second event is less traumatic than the original one. Many cases are persistent; about half recover within 1 year, but up to one-third do not recover even after many years (Kessler et al., 1995).

Diagnosis

The diagnostic criteria in ICD-10 and DSM-IV are similar, although the latter assigns rather more importance to numbing. DSM-IV includes two criteria that are not present in ICD-10—symptoms must have been present for at least 1 month, and must cause significant distress or impaired social functioning. As a result of these differences, the concordance between the diagnosis of PTSD using the two sets of criteria is only 35% (Andrews et al., 1999). By convention, PTSD can be diagnosed in people who have a history of psychiatric disorder before the stressful events.

Differential diagnoses include the following:

• stress-induced exacerbations of previous anxiety or mood disorders

• acute stress disorders (distinguished by the time course)

• adjustment disorders (distinguished by the different pattern of symptoms)

• enduring personality changes after catastrophic experience.

PTSD may present as deliberate self-harm or substance abuse which have developed as maladaptive coping strategies (see above).

Epidemiology

Estimates of PTSD in the general population have mainly been obtained from the USA. Rates in other countries are likely to differ somewhat in relation to the frequency of natural and man-made disasters in these places. In a large representative sample from the USA, Kessler et al. (1995), using DSM-III-R criteria, estimated a lifetime prevalence of PTSD of 7.8% (10.4% in women and 5.0% in men). A more recent epidemiological study conducted in the USA, employing DSM-IV diagnoses, found a rather similar lifetime risk of PTSD of 6.4% (Pietrzak et al., 2010). Estimates of the 12-month prevalence range from 1.1% in Europe (Darves-Bornoz et al., 2008) and 1.3% in Australia (Creamer et al., 2001) to 3.6% in the USA (Narrow et al., 2002)

Aetiology

The stressor

The necessary cause of PTSD is an exceptionally stressful event. It is not necessary that the person should have been harmed physically or threatened personally; those involved in other ways may develop the disorder—for example, the driver of a train in whose path someone has thrown himself for suicide, and the bystanders at a major accident. The authors of DSM-IV describe such events as involving actual or threatened death or serious injury or a threat to the physical integrity of the person or others. In a study of people affected by a volcanic eruption, the highest rate of PTSD was found among those who experienced the greatest exposure to the stressful events (Shore et al., 1989). Even so, not all of those most affected by the stressor developed PTSD, a finding which indicates that some form of personal vulnerability plays a part. Such vulnerability might be genetic or acquired. Epidemiological research has revealed the following findings:

• The majority of people will experience at least one traumatic event in their lifetime.

• Intentional acts of interpersonal violence, in particular combat and sexual assault, are more likely to lead to PTSD than accidents or disasters.

• Men tend to experience more traumatic events in general than women, but women experience more events that are likely to lead to PTSD (e.g. childhood sexual abuse, rape, and domestic violence).

• Women are also more likely to develop PTSD in response to a traumatic event than men. This enhanced risk is not explained by differences in the type of traumatic event.

Genetic factors

Studies of twins suggest that differences in susceptibility are in part genetic. True et al. (1993) studied 2224 monozygotic and 1818 dizygotic male twin pairs who had served in the US armed forces during the Vietnam War. After allowance had been made for the amount of exposure to combat, genetic variation accounted for about one-third of the variance in susceptibility to self-reported PTSD. Self-reported childhood and adolescent environment did not contribute substantially to this variance. The risk of PTSD is increased by a family history of psychiatric disorder, which may reflect genetic factors. Attempts to identify specific genes important in aetiology have not led to consistent findings (Cornellis et al., 2010).

Other predisposing factors

The individual factors that increase vulnerability to the development of PTSD have been summarized by Ahmed (2007). They include the following:

• personal history of mood and anxiety disorder

• previous history of trauma

• female gender

• neuroticism

• lower intelligence

• lack of social support.

Neurobiological factors

Research to date on the neurobiology of PTSD has focused on monoamine neurotransmitters and the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, both of which are involved in mediating defensive responses to stressful events. In addition, brain imaging studies have implicated changes in the hippocampus, a brain region that is important in memory formation, and the amygdala, which plays a role in non-conscious emotional processing (see Box 8.4). These findings suggest that hippocampal dysfunction prevents adequate memory processing, while increased activity in noradrenergic innervation of the amygdala increases arousal and facilitates the automatic encoding and recall of traumatic memories. Functional imaging studies in PTSD suggest overactivity of the amygdala in the context of decreased regulatory control of limbic regions by the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (Krystal and Neumeister, 2009). However, some have argued that forms of PTSD characterized by prominent dissociative symptoms (emotional detachment, derealization, and depersonalization) may in fact be characterized by excessive corticolimbic control (Lanius et al., 2010).

Psychological factors

Fear conditioning

Some patients with PTSD experience vivid memories of the traumatic events in response to sensory cues such as smells and sounds related to the stressful situation. This finding suggests that classical conditioning may be involved, as well as failure to extinguish conditioned responses (Jovanovic and Ressler, 2010).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree