INTRODUCTION

In one sense the broad principles of rehabilitation seem well and securely established. But in another sense they seem to be rediscovered anew by succeeding generations, with sometimes wise old concepts seeming to come newly dressed as fresh approaches. In England up to 70% of acute hospital beds are occupied by older people, a theme familiar to most ageing societies, focusing attention on how to promote recovery more rapidly and ensure it can be sustained, not least with older people with mental health problems.

Rehabilitation of the older person with psychiatric disorder means restoring and maintaining the highest possible level of psychological, physical and social function despite the disabling effects of illness. More broadly it also means preventing unnecessary handicap associated with illness, preventing unnecessary handicap secondary to maladaptive responses to illness and combating the deadening effects of low expectations for older people among professionals, patients, families and society in general. Managing chronic disease and disability is the greatest challenge to modern medicine. Within this, rehabilitation of many older people with psychiatric disorder looms large – although, of course, many old people with psychiatric disorder respond well to ‘curative’ therapy and require little rehabilitation.

In fact, rehabilitation has always been a fundamental and inseparable part of old age psychiatry (as of all psychiatry). Perhaps for this reason, as with rehabilitation in geriatric medicine1,2, little writing in the way of conclusive evaluation or substantial trials has addressed the topic specifically. Some particular techniques, such as psychological approaches with the cognitively impaired, have been well described3,4, but little evaluated5, and evaluative research is much needed here.

SPECIAL PROBLEMS WITH PSYCHIATRIC DISORDER IN THE OLDER PERSON

‘Old age’ may span 40 years or more, posing quite different rehabilitation problems; but the most major challenge is the very frail, the old old. In this group multiple disability is prominent, easily complicated by polypharmacy, and physical and mental ill health interact in complex ways. With this vulnerable population, disentangling the respective influences of ageing, previous personality and current ill health can be exacting. Two thirds of the UK’s disabled population are older people and the true extent of handicap due to psychiatric disorder is probably still not established.

With depression especially there may be restriction of physical activity, threatening physical capacity and health. Depression associated with stroke disorder6 or with Parkinson’s disease7 particularly illustrates both the connection between physical and psychiatric problems and the importance of physiotherapy and occupational therapy in psychiatric rehabilitation.

Physical factors are frequently of great importance in dementia. A quiescent individual may become delirious and disturbed at night through heart failure, obstructive airways disease or even the uncomfortable effects of severe constipation. Settling such problems may transform the reality of care for a carer and seeking out such therapeutic opportunities is an important part of rehabilitation. Similarly, in dementia physiotherapy and occupational therapy to promote and maintain the best possible physical capacity are key elements. Advice and practical aid to carers, such as with lifting and handling the physically disabled person with dementia, can be crucial.

A judicious mixture of the ‘therapeutic’ (curative) and the ‘prosthetic’ (supportive) approaches, sagely described over two decades ago by an eminent wise voice in geriatric medicine8,9, is very necessary in old age psychiatry. While much functional psychiatric disorder and delirium can be ‘cured’, and this must be the aim, most older people with dementia need some degree of supportive care at some stage. The poor financial and housing state of many older people, together with the lack of children or spouses to help as carers for many of the old old, are further complicating factors. Maximizing ‘participation’ despite psychiatric disorder needs to be a major goal: maintaining as far as possible a role in the family, social contact, a range of activities and minimization of loss of autonomy or institutionalization. This requires an approach which embraces psychiatric, medical, rehabilitation, nursing and social perspectives. Vigorously pursing active prevention of disability or of reduced participation as a consequence of psychiatric disorder is a vital part of rehabilitation.

SPECIAL PRINCIPLES IN REHABILITATION OF THE OLDER PERSON WITH PSYCHIATRIC DISORDER

Table 130.1 summarizes the principles. The home must be the focus of attention. This is where problems have arisen and where they

Table 130.1 Principles of rehabilitation for theolder person with psychiatric disorder

| Focus on the home |

| Ensure comprehensive assessment |

| Encourage normal function |

| Treat the treatable |

| Analyse disabilities and chart progress |

| Clarify team goals with patient and carers early |

| Clarify team goals with support workers early |

| Teach what can be relearned |

| Adapt the adaptable |

| Coordinate support and follow-up |

| Promote flexibility and ingenuity |

| Promote realistic optimism |

| Promote participation and autonomy |

will need to be overcome. Planning for rehabilitation should begin at the earliest moment; an initial assessment at home by a senior psychiatrist, or other experienced team member, is invaluable – even if ‘home’ by now is an institution in the community. Home is also where the carers, and often any social services support staff involved, may readily be found. It is where they will need to work with solutions. This contrasts with standard medical rehabilitation where traditionally often no such opportunities for outreach have existed.

Frequently, further assessment by, say, an occupational therapist, physiotherapist or another specialist team member may be necessary – and this can perhaps also be arranged at home. But avoiding disruptive admission should not be at the cost of really meeting assessment needs. The day hospital or a community-based therapy resource centre and their teams may often be useful to complete such assessments. They (or a day centre specially supported with outreach expertise) may be settings where important rehabilitation efforts can be made.

Effectively supporting the carers with people at home is essential for rehabilitation. In the UK, Admiral Nurses are a good example – specially trained mental health nurses who work all the time in the community with people with dementia and their carers.

Poor function or morbidity should never be accepted as immutable, and, still less, as normal. Assessment should aim at a thorough understanding of social, physical and psychological function as well as the previous pattern of personality and lifestyle. From this, diagnoses and specific treatment for the treatable should follow. But also analysis should show the extent of disability, how it is mediated and how it may be overcome. Problems should be clearly recorded, with proposed solutions and with regular review of progress, and with this it is useful to use standardized assessments, such as the Bristol Activities of Daily Living Scale (BADL)10, and a standardized framework, such as the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF)11. From the earliest moment, independent function and improvement should be sensitively encouraged, especially with hospitalized patients.

As early as possible, the agreed goals of rehabilitative efforts need to be clarified with the patient, with the relatives/carers, with the whole rehabilitation team and with any support workers needed in the community. Education, guidance and a rehabilitative ‘demonstration’ may well be necessary to resolve conflicting views on the prospects for progress. Carers may need therapy or rehabilitation in their own right. Almost always the support of carers is essential, though some stoutly independent patients manage well without this.

A prognosis-based plan is useful. This means assessing: what are the problems and what are their causes? Prognostication will follow: will these get better or worse? To what degree? Over how long a period? From this a plan can flow consistent with what seem the most major likely developments of a problematic nature, over a foreseeable time scale and taking account of what is most remediable.

Sometimes disability strongly distorts the previously stable power and dominance pattern in the family, first noted in classic work12 but reiterated in evolving family therapy work13, so that, for instance, a forceful mother becomes dependent on a passive daughter. Relationships are always important and such phenomena can strongly influence outcome. They need to be understood and often complex ambivalence worked through14. Such factors are frequently important when carers seem reluctant to resume caring14,15 and need to be carefully teased out when juggling with the various elements of risk and risk minimization involved in supporting a vulnerable person at home15. The patient’s ‘crutch is not made of wood but of some other person’s tolerance or patience’16.

An agreed balance should be sought between the needs of carers and the patient’s right and desire for continued comparative independence despite significant disability – bearing in mind the team’s prime responsibility to the patient.

In effect, carers should be ‘recruited’ as rehabilitation therapists’ ‘aids’. But often they will need practical help and advice on rehabilitation techniques, and, always, the reassurance of the services’ continuing availability for support and sensitive expert response. This is less easy both to offer and in practice as services increasingly become, as in recent years, driven towards short-term involvement and a short-term perspective.

Similar considerations apply with any support staff necessary to help the patient at home – principally social services staff in the UK. Their early involvement and integration into the assessment and rehabilitation process can be logistically difficult but generally is most effective. Again, a longer term perspective and continuity are invaluable.

Good teamwork is of the essence. Clarity and consistency within the multidisciplinary specialist team are essential. Nurses and therapists, for instance, must communicate well, each complementing and enhancing the other’s approach.

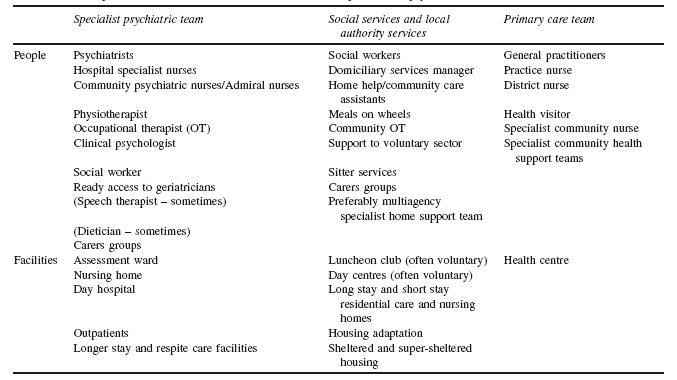

Specialist and general practitioner must be in accord. The specialist team must carry the confidence of those who will work with the patient outside hospital. (Table 130.2 lists many of the team members and resources requiring coordination for rehabilitation – inevitably there is great overlap.)

Clear goals should be set, in accord with those of the patient and carers, and clearly understood by all15,17–20. This is much easier said than done with the vulnerable frail older person; but vitally important is good communication.

Patients are taught what they can learn or relearn but often only modification of domestic equipment, provision of aids or modifications of the home will overcome their disability. More often still problems are only overcome through support services – home-delivered meals or a home help/community care assistant – coming into the home. Ingenuity and diplomacy may be needed with an old person reluctant to accept such necessary support. The great majority of support is provided by relatives/carers and supporting the supporters is the main task. This may require a day hospital or community venue for therapy, day care centre or respite admissions. Maintaining confidence that there will be reliable and appropriate care interventions and responses by the service is vital. Such confidence and such a reality become harder to maintain as there

Table 130.2 People and facilities to aid rehabilitation of the older person with psychiatric disorder

is more pressure on services to be short term in their outlook and activity.

At some stage with hospital patients, except in the most grossly deteriorated person, a home assessment is advisable with an occupational therapist or physiotherapist, or both, and perhaps with other team members.

Hospital-based staff can be too pessimistic and, allowed to function in her familiar environment, even a person with quite significant dementia can sometimes perform surprisingly well. Often serial home assessments are helpful with increasing challenge, leading to overnight stays. Also, failure initially to manage satisfactorily should not preclude the possibility of later improvement with further therapy or support.

A model of how a person-centred multi-agency specialist home support team for people with dementia and their carers works to achieve valued results has been quoted in the National Dementia Strategy20 and evaluated in pilot form21. This highlights many of the issues arising when striving for a more bespoke, individual approach.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree