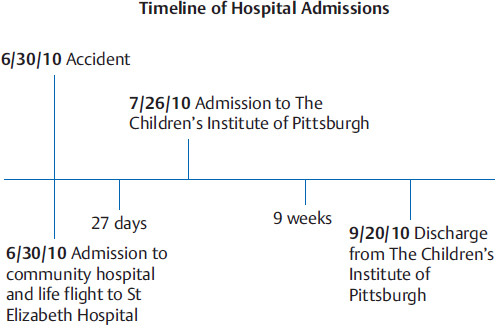

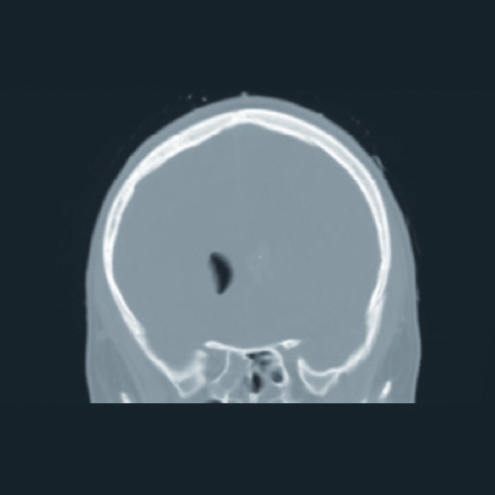

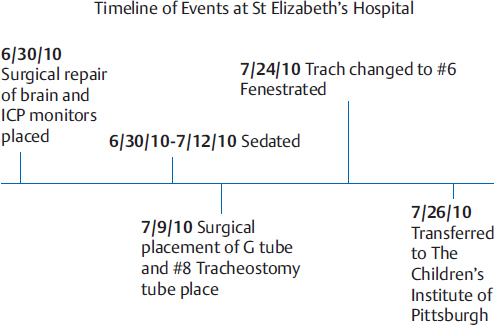

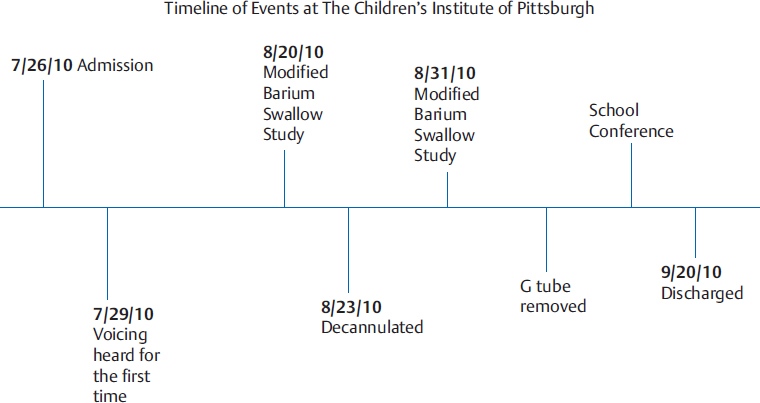

Case Report B2 Examination and Evaluation of Oral Feeding and Communication after a Gunshot Injury to the Head A gunshot wound to the head is a devastating event for the victim and family. Shootings are the fifth leading cause of unintentional death among American children under the age of 15.1 Firearm-related injuries are especially lethal; approximately two-thirds of these injuries result in death.2 Firearm-related death rates are highest among persons aged 15 to 34 years (8.5/100,000).2 In 2009, there were 76,100 emergency department visits for firearm-related injuries, 35% of which were for unintentional injuries.3 This case report explores what happened when a 14-year-old’s cousin accidently shot him in the head. It chronicles the recovery process of Russell, following him for 9 weeks, beginning with his admission to inpatient rehabilitation and concluding with his discharge home (Fig. B2.1). This report provides an overview of the care provided during Russell’s inpatient acute rehabilitation stay and explores the application of key principles of Neuro-Developmental Treatment (NDT) practice to the clinical management of an adolescent with traumatic brain injury (TBI) during the early phases of his rehabilitation program. It also provides an integrated view of Russell’s therapy programs, describing the interrelationships of his occupational therapy, physical therapy, and speech-language therapy programs from the viewpoint of his speech-language pathologist (SLP) within the context of an NDT framework of practice. The report chronicles Russell’s recovery process, identifying the sequential gains in abilities and the clinical decision-making process used by his medical rehabilitation team to enhance his functional independence. This case also explores the interrelationships of care provided by his SLP, occupational therapist (OT), and physical therapist (PT). From the speech-language therapy perspective, it explores gains in communication, feeding, and swallowing, and their relationships to the management of his tracheotomy tube, as well as the relationships to gains in locomotion and activities of daily living. When a life-altering, traumatic injury occurs to a child, parents/families often have difficulty prioritizing their goals. They want all their goals to be successfully achieved, often immediately, but when asked, most families want eating and some form of communication restored as quickly as possible. Russell was a healthy, active, typically developing 14-year-old boy who, on June 30, 2010, sustained an accidental gunshot wound to his head at 4:00 a.m. According to the parent’s report, he was sleeping overnight with his cousin. A neighbor heard an explosion, came to the cousin’s house, and called 911. The bullet had entered Russell’s forehead, continuing through the frontal lobes, penetrating through the ventricles, and exiting the occipital area, creating an open TBI. Russell was intubated at the scene and life-flighted to the hospital, where he underwent a computed tomographic (CT) scan of his brain (Fig. B2.2). He underwent surgical management for his head injuries on the date of admission. He was placed under sedation for several weeks (Fig. B2.3). His prognosis for recovery of any meaningful function was poor. The evidence cites that, when the wound is penetrating and enters more than one lobe and the ventricles, outcomes are poor with severe disability or death.4,5 Outcomes are considered poorer for those with extensive bullet tracts, those that cross deep midline structures of the brain, or those that involve the brainstem.6 Intracranial pressure monitors were placed, and his pressures were monitored while he was sedated. He had a gastrostomy tube (G-tube) placed 3 weeks into his acute care stay. Prior to this placement, he was nourished through intravenous therapy. He underwent a percutaneous tracheotomy 9 days into his acute care admission. He was treated with antibiotics for multiple fevers secondary to tracheitis and grew methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). When he was weaned from the sedation, his parents noted he was able to move his left extremities and inconsistently follow simple commands. His mother reported that at times he would shake his head yes and no, but this communication was not observed during the initial speech-language evaluation. Russell was admitted to The Children’s Institute of Pittsburgh on July 26, 2010 (see timeline in Fig. B2.4). He was functioning at a Rancho Los Amigos Level III at admission.7 This level is described as a patient showing localized responses to sensory stimuli and inconsistent responses to simple commands. A person at this level will • be awake on and off during the day. • make more movements than at Levels I and II. • react more specifically to what he sees, hears, or feels. For example, he may turn toward a sound, withdraw from pain, and attempt to watch a person move around the room. • react slowly and inconsistently. • begin to recognize family and friends. • follow some simple directions such as “look at me” or “squeeze my hand.” • begin to respond inconsistently to simple questions with “yes” or “no” head nods. Russell was not able to move in bed, transfer, or walk. He was totally dependent on others for any shifting of a position in bed. He could not sit without total support. Russell had no weight-bearing precautions upon admission. However he was at risk for falls. He had contact precautions, MRSA, and a left subclavian triple lumen catheter to deliver fluids and medications. He arrived with a fenestrated tracheotomy and gastrostomy tube. He was not able to communicate. He had no vision in his right eye and displayed a severe downward gaze secondary to bilateral cranial nerve, III, IV, and VI palsies. His parents were told that his right optic nerve was likely transected based on his CT scan. He presented with hyponatremia and was diagnosed with syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH). SIADH is an imbalance of sodium in the body. This is managed by restricting fluids and providing sodium supplementation. For months he required fluid restrictions and sodium supplementation. When he was able to safely drink, he was unable to do so due to SIADH. Russell’s past medical history indicated that he had been diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and attention deficit disorder (ADD) during childhood and was not currently on medication. He also underwent an appendectomy in 2008. Russell’s social/family history indicated that he lived with parents, two older sisters (ages 17 and 16), and an 18-year-old brother. Russell lived in a two-story home with 1 step to enter and 12 steps to the second floor. His bathroom was on the first floor, and his bedroom was on the second floor. The parents reported that a first floor bedroom setup was possible for him at home. Russell was entering the 9th grade at his local high school. Russell demonstrated the following activity limitations and impairments of body structures and functions at the time of admission. • He was nonverbal and was unable to eat. • He did not use vision and was unable to move and hold a position without total assistance of two people. • Russell presented with weakness throughout the upper and lower extremities and trunk, along with right hemiparesis, and was scored as Rancho Los Amigos Level III. He had poor motor control and poor initiation of movement bilaterally, but the right side was more impaired then the left. He had poor coordination bilaterally; more focused on the right. He demonstrated abnormal motor patterns on the right with low postural tone with spasticity. • He presented with proprioceptive and tactile impairments that were focused on the right side, vestibular impairments, and nausea when in upright positions. • He had paralysis due to injuries of cranial nerves III, IV, and VI. • He tired and fatigued easily. • Cognition, expression, and receptive language were severely impaired. • He had impaired memory. • Russell had impairment of regulation that resulted in an increased heart rate. • Russell had no transfer or mobility skills. • He had no communication or self-care abilities. • He had no leisure skills. The parents and family wanted Russell to return back to his baseline function. However, at admission he was functioning with total care for all needs. • Neuromuscular: Loss of postural motor control impaired his ability to initiate any movement. Hypotonic proximally with spasticity noted distally in the upper and lower extremities impaired his ability to move or maintain any postures against gravity. • Sensory: Moderately impaired proprioceptive, vestibular, tactile, and visual systems. • Musculoskeletal: Moderate to severe muscle weakness throughout the bilateral upper and lower extremities and trunk. Range of motion limitations for bilateral ankle dorsiflexion to neutral and popliteal angle of 43° on the right with hip flexed at 90°. • Respiratory: Admitted with fenestrated cuffed tracheostomy. He had an abdominal binder that inhibited diaphragmatic/abdominal breathing. The binder was being used to prevent him from pulling his gastrostomy tube out. Russell was treated by all disciplines for intensive therapy. He received physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech-language therapy services two times per day for each service. On the weekends, he received all services one time per day on Saturday and rested on Sunday. His mother was by his side constantly and was a key reason for his success. She attended therapies and practiced the skills during any down time. Some of the key transitions that occurred throughout his stay as observed by the SLP include the following. Russell wanted to eat orally but had been listed as receiving nothing by mouth since the accident. A fenestrated tracheostomy can cause more infections and adhesions and is usually reserved for use when someone is vented. Russell was no longer on a ventilator, so his tracheostomy was changed to a no. 6 Shiley tracheostomy tube (Medtronic). It was important to restore the pressurized system of the swallow by using a Passy-Muir speaking valve (Passy-Muir, Inc.). The speaking valve is a one-way valve that allows the patient to breathe in through the tracheostomy but forces the air up over the vocal folds and out the oral and/or nasal cavities. Restoring air to the oral and nasal cavities enhances taste and smell abilities. Since the change to the Shiley no. 6 tracheostomy tube, the larynx was more free to move in an upward and forward position to swallow because it was no longer tethered with the inflated cuff in the trachea. Therapy started with oral stimulation activities that quickly moved to water-based trials of smooth foods, such as applesauce. He would tire quickly because he had to maintain a supported upright position. In week 4 of his admission, the first swallow study was completed on August 20, 2010, with the tracheostomy present. He was safe for regular foods but unsafe for thin liquids. Russell silently aspirated on thin liquids. He penetrated into the airway with nectar thick liquids but cleared with a double swallow or a cough and swallow. See the video of Russell’s swallow study on Thieme MediaCenter. He was able to tolerate the Passy-Muir valve at all times and was moving toward capping and decannulation. His mother clearly understood the value of using a speaking valve and provided the valve for all Russell’s waking hours. The coordination Russell needed to adequately manage the thin liquid was emerging. See video on Thieme MediaCenter. The following impairments were observed at this time: • Decreased hyolaryngeal excursion. • Premature posterior bolus spillage. • Delay in initiation of a swallow. Speech-language therapy focused on increasing the volume of regular foods to decrease the need for tube feedings. He drank nectar-thick liquids with meals and thin liquids with speech-language therapy only. In therapy, he practiced with small amounts of thin liquids with an increasing awareness of the liquid “going the wrong way” and coughing. Coughing is a sign that the sensory receptors in the trachea are recovering, and Russell could feel when the liquid was aspirated or had penetrated. He also participated in activities to facilitate hyolaryngeal excursion range. This increased range helps to protect the airway from penetration and aspiration by pulling the larynx forward and narrowing the trachea, opening the upper esophageal sphincter to open the esophagus as the epiglottis rudders the bolus toward the esophagus. He was decannulated within a week of his first study. This decannulation helps because the laryngeal complex is no longer weighted by the tracheostomy tube. It was important to complete the modified barium swallow study as soon as it appeared that he would be successful with thin liquids. In this case, he was cleared within a week of tracheostomy tube removal. The second swallow study was completed August 31, 2010. He was safe for thin liquids. He quickly moved to a regular diet with thin liquids. See the video on Thieme MediaCenter. Upon admission, Russell had no vision in the right eye and a severe downward gaze. His mother and the SLP reported that he seemed to be using some vision. Russell first used his vision by lifting his face toward the ceiling to look at things before his eyes could move closer to midline. When the SLP played cards with him, such as Uno, he was first able to discriminate the colors and then the numbers. When Russell was in joint intervention with physical therapy and speech-language therapy, the PT also noted his improved visual skills. This seemed to help build momentum for others to observe his improving visual skills. Russell wore an abdominal binder to protect his gastrostomy tube from being pulled out. In a joint intervention session when the PT was working on ambulation, the PT was having difficulty cuing Russell at his abdominals due to the binder. When the binder was removed, he began more active and accurate steps with improving speed. The SLP requested to the physiatrist to remove the order to use the abdominal binder because Russell was no longer pulling the gastrostomy tube. In addition, he no longer used the tube because he was meeting all nutritional and medication needs orally. This request prompted her to remove not only the binder but also the gastrostomy tube. This is an example of how each team member can positively affect the recovery process by looking at the whole person as a dynamic, responsive, and ever-changing being. NDT principles teach us to observe and identify those needs as they change throughout the rehabilitation process. Cognitively, Russell was answering yes and no questions with better consistency and accuracy of correctness. However, his memory was so impaired that it was interfering with all facets of rehabilitation and learning. He was prescribed amantadine to stimulate his dopaminergic system and cognitive recovery. He tolerated the medicine well without side effects. After several weeks, he was weaned from the medicine without decline in memory or cognitive skills. Russell had poor self-monitoring skills, with frequent outbursts of silly sounds or saying burp with no actual burp. He showed no embarrassment for the time or the audience that was present. The amantadine helped to reduce these incidents and increase his self-awareness to the inappropriateness of these behaviors. Upon admission, Russell’s medical status required that he be reclined in sitting due to impairment in the vestibular-ocular system; when upright for prolonged periods of time, he experienced nausea and fatigue. A reclining wheelchair allowed him to rest when needed, without enduring the difficulties of transferring back to bed. Medically, Russell required a reclining wheelchair for the first 2 weeks of his admission. However, once over the initial phase of fatigue and as his tolerance for upright activities improved, he was ready to be transitioned to a standard-back, nonreclining wheelchair. This upright wheelchair was requested from the SLP. It allowed Russell to be more active in sitting, and, when in upright, he seemed more alert, with improvements noted in his cognitive and language skills. The other members of his medical rehabilitative team agreed the he was ready for less-supportive seating. Within the NDT Practice Model, all members of the team are encouraged to share their observations and insights and are empowered to make clinical recommendations to enhance the individual’s overall functional potential. Communication, language, and cognition fall within the traditional scope of practice for an SLP. For an SLP practicing with knowledge of NDT, there is an enhanced understanding of the importance of postural control and biomechanical alignment and their influences on the ability to produce sounds and engage in communication. As a member of an NDT team, the SLP is able to step outside the traditional bounds of speech-language therapy and embrace the child as a whole person. When doing so, the therapist can consider the needs of the whole person to enhance discipline-specific functional capabilities. At 9 weeks after admission, Russell had changed from total assist in all domains of care to moderate assist in grooming, bathing, and toileting, as measured by the WeeFIM II Instrument (Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation, UB Foundation Activities, Inc.). In the other domains, he primarily required minimal assist to supervision, while bowel and bladder management were rated as modified independence. Russell was discharged at Rancho Los Amigos Level V, which is labeled Confused-Inappropriate, Non-Agitated.7 A person at this level will • be able to pay attention for only a few minutes. • be confused and have difficulty making sense of things outside himself. • not know the date, where he is, or why he is in the hospital. • not be able to start or complete everyday activities, such as brushing his teeth, even when physically able, and often need step-by-step instructions. • become overloaded and restless when tired or when there are too many people around. • have a very poor memory; remember past events from before the accident better than his daily routine or information he has been told since the injury. • try to fill in gaps in memory by making things up (confabulation). • often get stuck on an idea or activity (perseveration) and need help switching to the next part of the activity. • focus on basic needs, such as eating, relieving pain, going back to bed, going to the bathroom, or going home. Russell was discharged home without any medications and with glasses and a gait belt. He could walk with some difficulty in clearing his right foot, which caused some balance issues when he did not clear it. He had not used a wheelchair in the last month of his stay. He could manage two flights of stairs with minimal supervision. Russell was very motivated to continue to improve his mobility skills. He would need to continue to work on improved gait and increased endurance. He was not appropriate for gym classes but would be continuing with physical therapy three times a week. Russell needed supervision in dressing with T-shirts and elastic pants. He could don and doff his shoes with minimal to no supervision. He needed total assist for tying his shoes. He wore an articulated ankle-foot orthosis (AFO) on his right foot. His visual motor skills were evaluated using the Beery Developmental Test of Visual-Motor Integration (VMI), and he scored at 5 years 6 months for handwriting. The Test of Visual Perceptual Skills (TVPS) scores ranged from 4.6 to 8.2 years. He needed to be cued to write his name and address. He needed multiple rest breaks when doing higher cognitive skills, such as school work. He wore glasses but had decreased depth perception. Russell was pleasant and cooperative. He performed best with 1:1 attention, especially when there were distractions or his attention was divided or he needed to shift between tasks. In academics, his reading and math skills were in the mildly impaired range of performance. He interacted with people appropriately. He spoke in conversations with others. He had mild word-finding difficulty but could be cued by group, location, action, or properties of the word. He was often impulsive in quickly saying, “I don’t know.” If he was cued to think first, he could try another answer. It was suggested that he always go back and check his written work. His memory was improving but he did better if information was presented in shorter chunks that were concrete rather than abstract. It was suggested that comprehension checks be done when longer or more complex information was presented. In terms of executive functioning, he could plan his own birthday party but had trouble organizing and retaining the information. Once strategies such as writing it down in a logbook were more habituated, he could use those tools to move on to the next planning phase, such as creating invitations. It was recommended that he return home with intensive therapies, three times a week for each discipline. He had homebound therapy and then went to outpatient therapies three times a week at a local hospital. Once he was able to tolerate that routine, he was placed back in school for mornings with an aide and then went to his therapies in the afternoon. It is expected that he will have continued recovery for the next 2 to 5 years. Berta Bobath said, “See what you see and not what you think you see.”8 We are sometimes so influenced by test results and professional observations that we may not take the time to listen to the families when they report that they are seeing better function. NDT teaches to listen to all that are involved with the patient and to try to be objective. In rehabilitation, the line between what is possible and what the evidence says is possible is a fine one. Russell arrived at The Children’s Institute with a poor prognosis due to the severity of the brain injury. However, the intense therapies and strong support from his mother and family defied his odds of recovery. NDT teaches us to be open to the possibility of change. You as a therapist may not expect change to happen just because the evidence tells you there will be a poor outcome; in this particular case the outcome was much better than the evidence would predict. If you allow past outcomes of others reported in the literature to dictate your prognosis, the child and the family will know that you do not believe in the possibility of success. Therefore, you will not look for the positives; instead, you will look for the things that will substantiate your belief that the outcome will be poor. In my mind, there were no limits to the possibility of a full recovery and to meet the goals of the family. NDT teaches us to look at the whole person. We do not work with a person that is to be divided by parts or disciplines. This is why it is so important to allow your view of the patient to be widened and to make suggestions; for example, changing the wheelchair or looking at his visual skills. We as therapists need to question and challenge each other and not see questioning as a threat or negative observation; rather, as a collaborative effort to meeting the needs of the patient. NDT offers the tools for an SLP to understand the whole physical aspect of rehabilitation and problem solving within a framework based on understanding in the movement sciences. Once an SLP understands the bigger picture and is able to integrate it into the field of speech pathology, the tool kit for therapy is greatly increased to meet the needs of the patients in the most efficient and effective manner. The outcome measure used during Russell’s rehabilitation stay was the WeeFIM II instrument. The WeeFIM instrument was developed to measure the need for assistance and the severity of disability in children between the ages of 6 months and 7 years. The WeeFIM instrument may be used with children above the age of 7 years as long as their functional abilities, as measured by the WeeFIM instrument, are below those expected of children aged 7 who do not have disabilities. The WeeFIM instrument consists of a minimal dataset of 18 items that measure functional performance in three domains: self-care, mobility, and cognition.9 Russell’s admission and discharge scores are listed in Fig. B2.5 and graphed in Fig. B2.6.

B2.1 Introduction

B2.2 Case Description

B2.2.1 Accident and Acute Care History

B2.2.2 Inpatient Rehabilitation Admission

Status at Admission

Analysis of Impairments of Body Systems

View from the Perspective of a Speech-Language Pathologist

Tracheostomy and Oral Trials

Swallow Study

Use of Vision

Abdominal Binder

Medical Management

Metacognition

Use of the Wheelchair—a Team Decision

Discharge

B2.3 Discussion of NDT

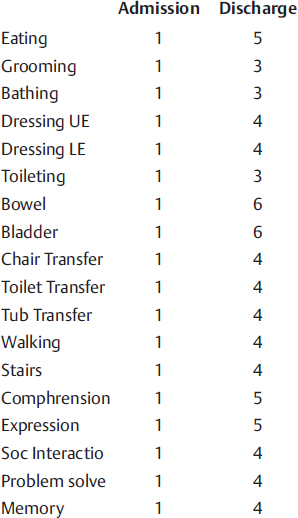

B2.4 Outcome Measurement Tool

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree