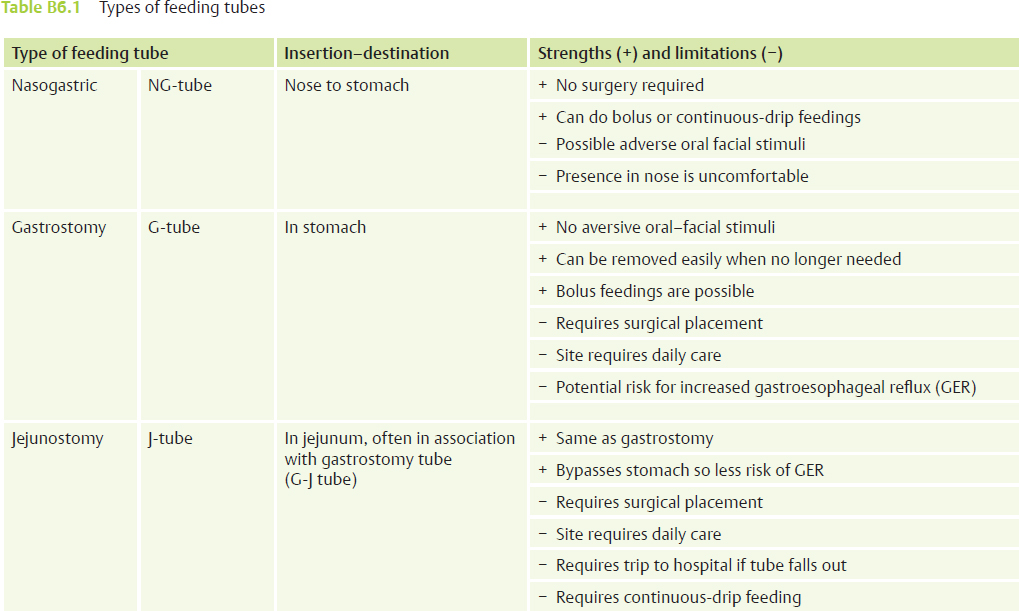

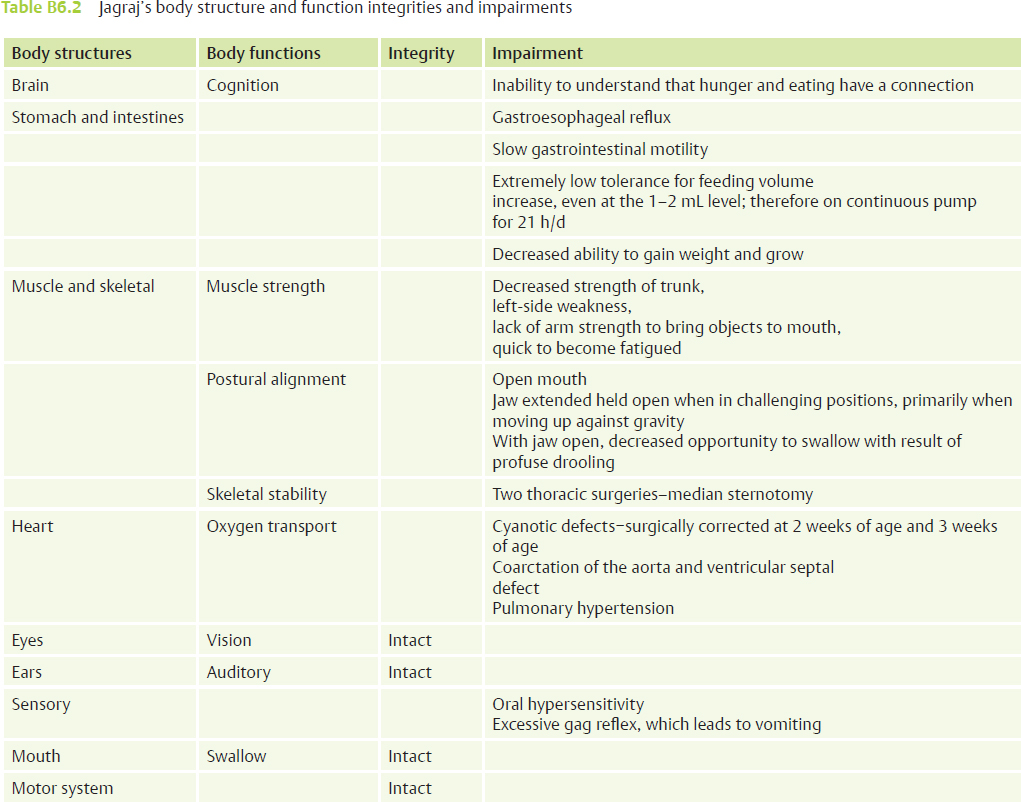

Case Report B6 Clinical Management of a Feeding Disorder in a Child with a Complex Medical Diagnosis For many children, the ability to eat and drink by mouth develops naturally during the first year of life, a seemingly innate skill. A speech-language pathologist (SLP), an occupational therapist (OT), or a physical therapist (PT) who specializes in working with children with feeding problems understands that the oral feeding and drinking process is a highly skilled, complex process that involves the interaction of multiple body structures and functions.1 Eating and drinking by mouth are multisystem processes with contributions from the sensory, motor, respiratory, and upper gastrointestinal (GI) and lower GI systems.2 A therapist with an understanding of the Neuro-Developmental Treatment (NDT) Practice Model will be cognizant of the contributions of each system but will also see the importance of postural control and postural stability as being the foundation with all areas of development, including gross motor, fine motor, and oral motor playing a role in the process of development of oral feeding skills. The foundation of basic feeding skills is grounded in postural stability and in the development of head control, shoulder girdle stability, and trunk control.3 When an infant is born with major dysfunction of one body structure, the impairments may influence the development of other body functions, and feeding skills can be severely affected, with impairment of function lasting for many years.4 Often, these medically fragile infants must receive their early nutritional sustenance through supplementary feeding tubes, such as a nasogastric tube or a gastrostomy or jejunoscopy tube.5 Table B6.1 describes the different types of feeding tubes. Although infants can then grow and thrive, they lack the experience of food in their mouth, which heightens their sensitivity issues and limits their development of the oral motor skills needed for learning to eat and drink by mouth.5,6 Learned oral aversion and lack of oral sensory experience and practice at a critical age often develop when infants are born with medical conditions that necessitate invasive diagnostic procedures and medical interventions, including surgeries that require long-term hospital-based recovery periods. These types of events during infancy may have a significant influence on early development in many areas, including gross motor, fine motor, social and emotional, oral motor, and early play and communication.7 Although an infant can often “catch up” in many areas of development once the original medical issue is resolved, some areas continue to feel the influence and require long-term intervention to resolve the effects of that early medical experience. One key area of development that can continue to reflect the effects of the negative experiences of the medical treatment is the area of oral feeding skills.8 In the past 15 years, the medical community, including doctors, nurses, and therapists, have become far more aware of the potential long-term negative influence of early necessary but invasive medical procedures on the development of feeding skills in infants and young children.5 This awareness has resulted in early intervention, often even while the infant is still in the special care nursery of the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). The medical team works to involve parents and to support the infant through positioning and early positive oral experiences to minimize the negative influence of the necessary medical procedures.1 Intervention at an early stage of recovery can begin to build the foundation for later development of oral feeding skills, even while the infant is receiving nutrition through supplementary feeding tubes.7,9 Even with this early recognition of the need for support and the efforts to provide that support, the journey toward oral feeding may be a long one, even lasting for years, for many children. This case report is one such journey for Jagraj, a boy who, at the age of 4 years, is still on his journey toward eating and drinking by mouth. Jagraj was born full term (birth weight 7 lb 7 oz) on October 24, 2008. He was the firstborn son in a Punjabi home. At 2 days of age, he was transferred to the Special Care Nursery at the local children’s hospital. His medical issues at birth included coarctation of the aorta and ventricular septal defect (VSD), for which he had corrective open heart surgery at 2 weeks of age. Jagraj was also diagnosed with pulmonary hypertension and acute respiratory failure and was on a ventilator during his hospital stay. That initial cardiac surgery was followed at 3 weeks of age by a second surgery to repair his diaphragm to improve his respiratory status. At that time, a gastrostomy–jejunostomy tube (G-J tube) was placed for feeding because Jagraj was unable to maintain his nutritional needs through oral feeding and had been diagnosed with failure to thrive. After the second surgery, Jagraj remained in the hospital for another 6 weeks, positioned in supine to promote recovery. This static positioning was necessary for Jagraj to facilitate postoperative healing, but it limited his early exploration of movement and sensorimotor experiences during a critical period of development. During the first 3 months of life, the infant begins to develop head and trunk control against gravity, stability of the shoulder girdle complex, and segmental mobility of the rib cage. Experiences of being held and moved through space and being positioned in prone, side lying, and supported sitting collectively contribute to the infant’s ability to act and interact with his world.10 These were experiences Jagraj missed as he lay on his back on his wedge, first in the hospital and later at home. In addition to his cardiac disorder, Jagraj was also diagnosed with gastroesophageal reflux (GER). He vomited with every feeding, and even without feeding, multiple times a day. A G-J tube was placed at 3 weeks of age with a continuous drip established directly into his small intestine, bypassing his stomach, except for medication. Thus, at a time when a newborn infant should be developing early feeding skills through breast feeding with his mother, experiencing the pleasant sensation of being full after being hungry, and then being cozy and comfortable in her arms, Jagraj was throwing up every time he felt food in his digestive system and had to remain on the wedge on his back, even when he felt sick. His mother was equally traumatized, wanting to protect her new baby and to feed him. Instead, she had to watch him in the crib, with tubes connected to every orifice, strapped flat with his huge chest wound healing. She had to watch him throw up repeatedly, even with the feeding tube. This picture is far too familiar to therapists who specialize in feeding, working with mothers and their children at 2 and 3 years of age with this medical history who continue to struggle with feeding issues. Ten weeks after he was born, Jagraj had healed from the heart surgery and was discharged home on oxygen on December 23, 2008. He weighed 9 lb at the time of discharge. However, the necessary medical intervention had influenced all areas of his early development, including his development of motor skills, his development of early play and communication skills, and most significantly, his development of oral feeding and drinking skills. In typical development at 5 months, infants are active in prone, beginning to roll in both directions, and beginning to sit with minimal support, head upright and arms free to reach and grasp, with hands and objects coming to their mouth for exploration.10 At 5 months of age, when Jagraj arrived at the therapy center for his initial evaluation, he had only been in supine, held in arms, or seated slightly reclined on a wedge, in a car seat, or in an infant recliner. In prone, Jagraj could not lift his head off the surface and was unable to push himself up onto his forearms. When placed on his stomach, as the family had been instructed, to build his strength and stamina, Jagraj quickly began to fuss and then cry in protest. His mother or grandmother would then immediately pick him up to comfort him and stop his crying. With no encouragement to remain in prone, Jagraj’s overall stamina remained poor, and marked weakness was noted, particularly in his shoulder girdle and abdominal musculature. He continued to be unable to take weight on his arms to push up into head and trunk extension to look around. He was unable to roll from back to front or front to back and, as a result, did not activate his rectus abdominis or obliques, which he needed to move himself upright into sitting. With the combination of weak abdominals and poor shoulder girdle strength and stability, Jagraj was unable to transition up against gravity from prone/supine to sit and later from sit onto all fours for crawling. Jagraj did not sit independently until he was almost 9 months old, and then he needed to be placed in sitting because he was unable to transition up independently. He resisted attempts to assist him onto his hands and knees. The result of this chain of effects, beginning with the original medical problem that necessitated early immobility, was an ongoing influence on the whole child in all developmental domains, including mobility, social, self-care (including feeding), and communication.11 In addition to wanting to comfort and protect this baby, the firstborn son who had suffered so much, Jagraj’s family was driven by another factor. When Jagraj cried, he vomited and lost whatever calories he had been fed. Caloric intake and weight gain were already a significant issue, as indicated in the diagnosis of failure to thrive. Thus, in addition to wanting to provide comfort, his mother and grandmother also wanted to prevent his vomiting so he could grow. Note that the other factor that triggered vomiting was any stimulation to his mouth. As a result, Jagraj consistently resisted any attempts to help him bring hands or objects, including a nipple, to his mouth with the consequence being increasing hypersensitivity and gagging that consistently cycled to vomiting. The result of this situation was threefold: first, Jagraj was making no changes in his development of gross motor skills, including strengthening of his shoulder girdle and trunk, which would strengthen the abdominals to help decrease the reflux activity12; second, Jagraj’s negative connection to his mouth with subsequent oral aversion was progressing with the lack of successful oral play5; and third, the family’s response to Jagraj’s crying was reinforcing his experience that crying worked as a successful communication tool.7 Over time, the last aspect of the situation would slow Jagraj’s progress in areas of social interaction and early communication. The following International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) model summary describes Jagraj’s capabilities at the time of his initial examination at the Children’s Therapy Center at 5 months of age. • Contextual factors. • Participation. • Participation restriction. • Activity. • Activity limitation. Table B6.2 presents Jagraj’s body structure and function integrities and impairments.

B6.1 Introduction

B6.2 Early Feeding Skill Development in the Presence of Medical Interventions

B6.3 Jagraj’s Birth and Medical Needs

B6.4 Jagraj’s Development

B6.5 A Summary of Jagraj’s Health and Disability According to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Model

Involved and motivated family who cherish and love Jagraj and want to do exactly what he needs to thrive and grow.

Involved and motivated family who cherish and love Jagraj and want to do exactly what he needs to thrive and grow.

Firstborn son in Punjabi home.

Firstborn son in Punjabi home.

Family includes parents and paternal grandparents in same house with no other children.

Family includes parents and paternal grandparents in same house with no other children.

Grandmother’s full attention focused on her only grandson.

Grandmother’s full attention focused on her only grandson.

New baby with severe medical needs with instruction given to family to avoid activities that cause vomiting (i.e., crying causes vomiting, therefore avoid activities that cause baby to cry).

New baby with severe medical needs with instruction given to family to avoid activities that cause vomiting (i.e., crying causes vomiting, therefore avoid activities that cause baby to cry).

Medically stable enough to come home from hospital at 3 months of age.

Medically stable enough to come home from hospital at 3 months of age.

Lives at home with parents and grandparents.

Lives at home with parents and grandparents.

Unable to eat with family at mealtimes.

Unable to eat with family at mealtimes.

Unable to actively explore his world.

Unable to actively explore his world.

Fed through jejunoscopy tube (j-tube) on continuous feed on a pump.

Fed through jejunoscopy tube (j-tube) on continuous feed on a pump.

Gastrostomy tube used for medications.

Gastrostomy tube used for medications.

Nicely engages adults with eye contact when held in front, or as he lays reclined in car seat, infant bouncy seat, or infant recliner.

Nicely engages adults with eye contact when held in front, or as he lays reclined in car seat, infant bouncy seat, or infant recliner.

In full supported sit, beginning to hold head more upright to look around and to look at adult in front of him.

In full supported sit, beginning to hold head more upright to look around and to look at adult in front of him.

Open to very short movement facilitation to provide him with movement experience in prone and supine.

Open to very short movement facilitation to provide him with movement experience in prone and supine.

Enjoys being held in upright to look around his environment.

Enjoys being held in upright to look around his environment.

Will bring hands together and hold.

Will bring hands together and hold.

Will grasp a toy or spoon and hold it for 10 to 15 seconds.

Will grasp a toy or spoon and hold it for 10 to 15 seconds.

Will sometimes touch toy to his own lips momentarily.

Will sometimes touch toy to his own lips momentarily.

No experiences with moving; subsequent lack of interest in moving as well as being placed on his tummy.

No experiences with moving; subsequent lack of interest in moving as well as being placed on his tummy.

Unable to push himself up on forearms and hold head up to look around.

Unable to push himself up on forearms and hold head up to look around.

Unable to tolerate tummy time for more than 5 seconds without crying and soon vomiting.

Unable to tolerate tummy time for more than 5 seconds without crying and soon vomiting.

No oral eating or drinking—no experience with full/empty tummy cycle, with consequence of no experience of hunger cues therefore no sense of appetite to drive interest in oral feeding.

No oral eating or drinking—no experience with full/empty tummy cycle, with consequence of no experience of hunger cues therefore no sense of appetite to drive interest in oral feeding.

No objects or hands to mouth due to learned oral aversion.

No objects or hands to mouth due to learned oral aversion.

Will not bring toy or spoon to mouth to explore for longer than 5 to 8 seconds.

Will not bring toy or spoon to mouth to explore for longer than 5 to 8 seconds.

Responds to sight of bottle by fussing and turning away, clear signs of oral aversion.

Responds to sight of bottle by fussing and turning away, clear signs of oral aversion.

Will not touch toy to his own lips if someone else is holding.

Will not touch toy to his own lips if someone else is holding.

Gags on tastes of formula or baby food touched to lips.

Gags on tastes of formula or baby food touched to lips.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree