48 Retroperitoneal Approaches to the Thoracolumbar Spine

I. Key Points

– Of utmost importance to performing any ventrolateral approaches to the lumbar spine is extensive knowledge of the regional anatomy, including the abdominal wall, peritoneal contents, retroperitoneal contents, and ventrolateral musculature and neural elements.

– Conventional open anterior (transperitoneal) approaches to the lumbar spine require mobilization of the sympathetic plexus and great vessels, which is associated with a significant incidence of complications. Retroperitoneal approaches to the lumbar spine minimize the incidence of such complications by avoiding mobilization of the large bowel, sympathetic plexus, and great vessels.

– The indications to perform a particular type of approach are more dependent on the localization of the pathology, the balance between advantages and disadvantages, and the surgeon’s knowledge of the approach than on the pathology itself. For example, the indications to perform an interbody fusion range from preoperative segmental instability to iatrogenic instability due to wide decompressions, but do not dictate a specific approach. In other words, the indications for a minimally invasive interbody fusion are the same as for an open interbody fusion. However, the relative localization of the instability, the skill of the surgeon, complication risks, and the health status of the patient indicate the preferential use of a particular approach over another (i.e., retroperitoneal versus transperitoneal).

– In general, left-sided approaches are more practical than right-sided approaches because it is less difficult to separate the aorta from the spine than to separate the more delicate inferior vena cava, particularly in cases of retroperitoneal fibrosis that occur in patients previously treated with radiation therapy due to neoplasms.

II. Conventional Open Retroperitoneal Access

– Indications

• Open retroperitoneal access provides a wide anterior exposure to the spine, allowing for the treatment of spine pathologies of degenerative, traumatic, and neoplastic origins. The most widely used approach is to perform anterior lumbar interbody fusions to treat a variety of spine pathologies that develop due to degenerative and neoplastic spine diseases, such as degenerative disc disease, trauma-related internal disc disruption, pseudarthrosis, decompression for neural stenosis, and spine deformity.1–3 This approach can also been employed to perform anterior access lumbar corpectomies1,2,4; it is also a common avenue for treating epidural spinal neoplasms and cases of complex spine deformity.

– Surgical technique varies with the level accessed.

• Lumbosacral (L2 to S1)1

A paramedian incision traversing the subcutaneous tissue to expose the external oblique muscle is made, preferably on the left to avoid the more prominent common iliac vein on the right. The external oblique muscle is then incised at the medial aponeurotic region, after which the rectus sheath is opened. The rectus muscle is then mobilized mediolaterally to preserve segmental innervation of the abdominal wall.

A paramedian incision traversing the subcutaneous tissue to expose the external oblique muscle is made, preferably on the left to avoid the more prominent common iliac vein on the right. The external oblique muscle is then incised at the medial aponeurotic region, after which the rectus sheath is opened. The rectus muscle is then mobilized mediolaterally to preserve segmental innervation of the abdominal wall.

Following mobilization of the rectus muscle, the retroperitoneal space is developed at the level of the semilunar line. This is done by dissecting the peritoneum in a lateromedial direction, freeing it from the superficial posterior rectus sheath (superior to the semilunar line). The peritoneal sac is then bluntly dissected off the psoas muscle, allowing for retroperitoneal access to the lumbar spine (it is important to identify and follow the ipsilateral ureter to identify the left iliac vein and artery).

Following mobilization of the rectus muscle, the retroperitoneal space is developed at the level of the semilunar line. This is done by dissecting the peritoneum in a lateromedial direction, freeing it from the superficial posterior rectus sheath (superior to the semilunar line). The peritoneal sac is then bluntly dissected off the psoas muscle, allowing for retroperitoneal access to the lumbar spine (it is important to identify and follow the ipsilateral ureter to identify the left iliac vein and artery).

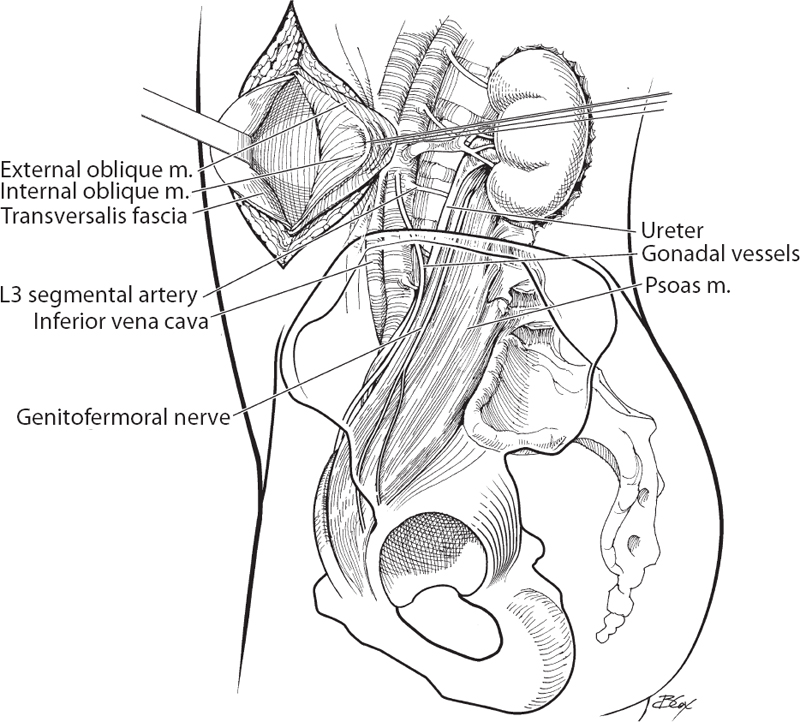

Exposure is then assisted by a self-retaining retractor (Omni-Retractor, Omni, St. Paul, MN). The left iliac artery and vein are retracted medially and segmental vessels divided laterally. It is crucial to avoid injury to vascular and lymphatic structures (Fig. 48.1).

Exposure is then assisted by a self-retaining retractor (Omni-Retractor, Omni, St. Paul, MN). The left iliac artery and vein are retracted medially and segmental vessels divided laterally. It is crucial to avoid injury to vascular and lymphatic structures (Fig. 48.1).

Following completion of the procedure, hemostasis should be confirmed and the self-retractor blades removed one by one to ensure a dry field. The wound is then irrigated and the abdominal wall reconstructed in plane-by-plane fashion.

Following completion of the procedure, hemostasis should be confirmed and the self-retractor blades removed one by one to ensure a dry field. The wound is then irrigated and the abdominal wall reconstructed in plane-by-plane fashion.

• Thoracolumbar (T12 to L2): thoracoabdominal approach1

The patient is secured in the lateral decubitus position. Approach is mostly via the left side.

The patient is secured in the lateral decubitus position. Approach is mostly via the left side.

An obliquely oriented thoracoabdominal incision is made and extended from the tenth or eleventh rib to the abdominal wall.

An obliquely oriented thoracoabdominal incision is made and extended from the tenth or eleventh rib to the abdominal wall.

The rib is dissected free from its bed via division of subcutaneous tissues, serratus anterior, latissimus dorsi, and intercostal muscles. The rib should be exposed at its superior border to avoid the neurovascular bundle below. The rib dissection is followed obliquely to the abdominal wall by dividing the external and internal oblique muscles. However, this distance should be limited to minimize postoperative muscular dysfunction. The transversalis layer is visible deep to the split costal margin and can be divided to expose the peritoneum.

The rib is dissected free from its bed via division of subcutaneous tissues, serratus anterior, latissimus dorsi, and intercostal muscles. The rib should be exposed at its superior border to avoid the neurovascular bundle below. The rib dissection is followed obliquely to the abdominal wall by dividing the external and internal oblique muscles. However, this distance should be limited to minimize postoperative muscular dysfunction. The transversalis layer is visible deep to the split costal margin and can be divided to expose the peritoneum.

The peritoneum is ventrally dissected of overlying structures (diaphragm and psoas muscle) to open the retroperitoneal space.

The peritoneum is ventrally dissected of overlying structures (diaphragm and psoas muscle) to open the retroperitoneal space.

The diaphragm is taken down, leaving a distal cuff for repair, avoiding the more central region to prevent damage to the phrenic nerve. The lung is gently compressed cranially with a moist lap pad. The parietal pleura is now visualized and can be opened to access the anterior thoracolumbar spine.

The diaphragm is taken down, leaving a distal cuff for repair, avoiding the more central region to prevent damage to the phrenic nerve. The lung is gently compressed cranially with a moist lap pad. The parietal pleura is now visualized and can be opened to access the anterior thoracolumbar spine.

For access to the anterior disc space, segmental vessels to the vertebral bodies are dissected and divided. These vessels must be handled with the utmost care as they pose a significant risk for hemorrhage and are a vital supply to both intra- and extraspinal structures. Some advocate preoperative angiography of the artery of Adamkiewicz to assist surgical approach and diminish the risk of paraplegia. Care should also be employed to prevent injury to retroperitoneal lymphatics (cisterna chyli and thoracic duct) and the development of large lymphoceles.

For access to the anterior disc space, segmental vessels to the vertebral bodies are dissected and divided. These vessels must be handled with the utmost care as they pose a significant risk for hemorrhage and are a vital supply to both intra- and extraspinal structures. Some advocate preoperative angiography of the artery of Adamkiewicz to assist surgical approach and diminish the risk of paraplegia. Care should also be employed to prevent injury to retroperitoneal lymphatics (cisterna chyli and thoracic duct) and the development of large lymphoceles.

Following completion of the procedure, if the diaphragm was incised, a large-bore chest tube is applied and the diaphragm repaired with nonabsorbable sutures. The thoracic cavity is then closed by employing rib-approximating sutures and repairing the intercostalis musculature. The anterior abdominal wall, serratus anterior, and latissimus dorsi muscles are reapproximated and reconstructed plane by plane via running nonabsorbable sutures.

Following completion of the procedure, if the diaphragm was incised, a large-bore chest tube is applied and the diaphragm repaired with nonabsorbable sutures. The thoracic cavity is then closed by employing rib-approximating sutures and repairing the intercostalis musculature. The anterior abdominal wall, serratus anterior, and latissimus dorsi muscles are reapproximated and reconstructed plane by plane via running nonabsorbable sutures.

• Management of vascular anatomy

Vascular concerns related to such approaches include managing the aorta, inferior vena cava, iliac vessels, iliolumbar vein, and segmental vessels.

Vascular concerns related to such approaches include managing the aorta, inferior vena cava, iliac vessels, iliolumbar vein, and segmental vessels.

With regard to the major vessels in the thoracolumbar and lumbar regions, the aorta usually is more toward the left side of the spinal column and the inferior vena cava is more toward the right side. Such anatomy should be reviewed and confirmed preoperatively. Most surgeons prefer to approach the patient from the left, as aortic damage is easier to repair than damage to the vena cava. However, if pathology is eccentric to one side, the surgeon should be prepared to approach from either side.

With regard to the major vessels in the thoracolumbar and lumbar regions, the aorta usually is more toward the left side of the spinal column and the inferior vena cava is more toward the right side. Such anatomy should be reviewed and confirmed preoperatively. Most surgeons prefer to approach the patient from the left, as aortic damage is easier to repair than damage to the vena cava. However, if pathology is eccentric to one side, the surgeon should be prepared to approach from either side.

Iliac vessels, which are the caudal extensions of the aorta and inferior vena cava, usually are not encountered with a lateral approach unless L5 is involved with the pathology.

Iliac vessels, which are the caudal extensions of the aorta and inferior vena cava, usually are not encountered with a lateral approach unless L5 is involved with the pathology.

The iliolumbar vein is an important direct tether in a left-sided dissection at L4-L5 or lower. This lumbar vein crosses from the inferior vena cava to approximately the level of the L5 body. Any dissection that exposes L4-L5 to the left of the left common iliac vein and inferior vena cava requires the identification, ligation, and division of the iliolumbar vein. Start at the L4-L5 disc and dissect distally to the L5 body until the iliolumbar vein is visualized.

The iliolumbar vein is an important direct tether in a left-sided dissection at L4-L5 or lower. This lumbar vein crosses from the inferior vena cava to approximately the level of the L5 body. Any dissection that exposes L4-L5 to the left of the left common iliac vein and inferior vena cava requires the identification, ligation, and division of the iliolumbar vein. Start at the L4-L5 disc and dissect distally to the L5 body until the iliolumbar vein is visualized.

Segmental arteries and veins lie at the lateral aspect of the vertebral bodies within the “valleys” of the lateral spine. Such vessels must be identified and ligated prior to exposure of the lateral vertebral body with subperiosteal dissection. If a segmental artery is sectioned with a Bovie cautery device (Bovie Medical Corp., Clearwater, FL), it may retract toward the aorta and continue bleeding. Therefore, early identification and ligation are paramount with exposure.

Segmental arteries and veins lie at the lateral aspect of the vertebral bodies within the “valleys” of the lateral spine. Such vessels must be identified and ligated prior to exposure of the lateral vertebral body with subperiosteal dissection. If a segmental artery is sectioned with a Bovie cautery device (Bovie Medical Corp., Clearwater, FL), it may retract toward the aorta and continue bleeding. Therefore, early identification and ligation are paramount with exposure.

– Complications

• Retroperitoneal fibrosis, rectus muscle hematoma, pancreatitis, femoral nerve palsy, ureteral injuries, lymphoceles, pseudomeningocele, latissimus dorsi rupture, impotence, and retrograde ejaculation2,5,6

• Acutely developing lymphoceles can be remedied by oversewing the lymphatic chain with a nonabsorbable suture.

– Outcomes

• Advantages of a conventional open retroperitoneal approach relative to a posterior approach include higher rates of fusion due to the ability to place larger interbody fusion devices, the ability to perform more complete disc excisions, and a reduced incidence of nerve damage. Furthermore, this approach is associated with decreased pulmonary complications and length of hospital stay.

• A conventional retroperitoneal approach is also associated with better outcomes in comparison with an anterior transperitoneal approach. For example, in addition to avoidance of large-vessel and bowel injury, the retroperitoneal approach is associated with a decreased incidence of retrograde ejaculation for exposures of L4-L5.

Fig. 48.1 Lateral view of the retroperitoneal approach to the lumbar spine.

III. General Postoperative Care for Retroperitoneal Approaches

– Retroperitoneal approaches do not typically require bowel rest in the postoperative period, unlike the transperitoneal approach. Nonetheless, although infrequent, bowel injury can occur via a retroperitoneal approach and is primarily identified by ileus and/or peritoneal irritation. Therefore, caution must be taken to identify and assess patients demonstrating signs of peritoneal irritation or dysfunction such as an absence of flatus.

– Patients should be monitored for the development of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and potential pulmonary embolisms (PEs). Patients are at high risk for developing DVT or PEs due to the significant manipulation of the deep veins (particularly the iliac vein), which commonly leads to the formation of venous thrombi.

IV. Surgical Pearls

– As a general rule in any spine surgery, segmental vessels obstructing the target structure must be ligated on the anterior portion of the vertebral body to preserve optimal collateral circulation to the neuroforamen and spinal cord.

– In mobilizing or traversing the psoas muscle, two things should be considered. First, it is beneficial to stay on the anterior third of the psoas muscle to prevent nerve root injury. Second, it is important to visualize and protect the genitofemoral nerve running on the surface of the psoas muscle. This prevents complications such as retrograde ejaculation or paresthesias of the anterior thigh.

Common Clinical Questions

1. Retroperitoneal approaches are preferentially done on the left side of the patient for all the following reasons except:

A. It is generally safer to mobilize the aorta than the inferior vena cava

B. The common iliac vein may be more prominent on the right side

C. The presence of the liver may minimize exposure

D. The left ureter is less susceptible to injury than the right ureter

2. Complications of retroperitoneal exposure include all of the following except:

A. Retroperitoneal fibrosis

B. Appendicitis

C. Ureteral injury

D. Femoral nerve palsy

3. To obtain adequate exposure, an essential component of the thoracoabdominal approach is:

A. Incising the diaphragm along along the costal margin and leaving a cuff attached to the rib

B. Transecting the psoas to allow full retraction of the muscle

C. Dissection of the lumbar plexus from the overlying psoas muscle

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree