49 Schwannoma A 46-year-old, right-handed female presented to the neurosurgical clinic with a three and a half year history of slowly progressive left arm pain. She described the pain as sharp and shooting, located in the lateral aspect of the upper arm and exacerbated by local pressure. Radiation of pain both proximally into the lateral arm and distally down the posterolateral forearm occurred during exacerbations. Initially the pain was intermittent in nature, but over the last year had become constant with frequent exacerbations. On occasion, the pain awoke the patient from sleep, especially while she was sleeping on the left arm. The patient complained of mild subjective numbness to the back of the wrist, but otherwise denied paresthesias or weakness. She was otherwise completely healthy with no significant past medical history. The patient took no medications, had no drug allergies, and was a nonsmoker and a social user of alcohol. There was no family history of neurofibromatosis. Functional inquiry was negative. Physical examination revealed a healthy-looking woman with no cutaneous manifestations of neurofibromatosis. There was no indication of muscle atrophy in the left arm. Palpation revealed a small mass deep to the brachialis muscle in the left lateral upper arm several centimeters above the elbow. Palpation over this mass triggered radiation of pain proximally and distally in the arm. Muscle power was normal in all muscles. Sensory examination revealed slightly decreased pinprick and light touch in the anatomical snuff box of the left hand and was otherwise normal. Reflexes were normal throughout. Magnetic resonance imaging of the left arm revealed a 1.0 x 1.5 cm mass in close association with the radial nerve. The mass was located in the intermuscular septum between the brachialis and brachioradialis, ˜5 cm proximal to the elbow joint. It was of low intensity on T1-weighted images, high signal intensity on T2-weighted images, and homogeneously enhanced with administration of gadolinium. Nerve conduction studies (NCSs) and electromyography (EMG) were found to be normal. In the operating room this tumor was identified in the groove between the brachialis and brachioradialis muscles. The mass was noted to be intimately associated with the nerve. Nerve action potentials (NAPs) of the radial nerve were conducted across the tumor and no abnormality was found. Microneurosurgical techniques were used to dissect the tumor free of the radial nerve fascicles, which were largely spread over the tumor capsule. A single fascicle was noted to enter and exit the tumor. The tumor was removed after coagulation of this single fascicle. Electrophysiological studies postexcision were unchanged from initial studies. The tumor pathological examination noted typical histological features of schwannoma. Postoperatively the patient did extremely well. There was no new neurological deficit and almost complete resolution of her pain. Now over 3 years postoperatively, there has been no recurrence. Schwannoma (of radial nerve) There are several clinical features of neural sheath tumors that can help to differentiate them from other lesions included in the differential diagnosis of a general soft tissue mass (Table 49–1). Unfortunately, there are no pathognomonic features that allow absolute differentiation of schwannomas from neurofibromas on clinical grounds alone. Schwannomas are generally deep-seated lesions with a slow and insidious growth pattern. They are laterally, but not longitudinally, mobile, with respect to their nerve of origin. Peripheral schwannomas are more commonly found in nerves of the head and neck or on the flexor surfaces of the extremities, and for unknown reasons preferentially develop on sensory nerves. No etiologic factors have been elicited, and no apparent racial or gender preference has been identified. Classically, schwannomas have been described as palpable, painless masses. In a large series of peripheral nerve schwannomas, 96% of patients presented with a palpable mass. This same series reports only 31% of patients as having spontaneous pain with schwannomas, although the reported incidence of pain varies from 0 to 100% in other smaller series. Referred dysesthesia (Tinel sign) when tapping or percussing over the mass is also a very common clinical finding.

Case Presentation

Case Presentation

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

| I. Nerve sheath origin |

| A. Benign |

| Schwannoma |

| Neurofibroma |

| Perineurinoma |

| Granular cell tumor |

| B. Malignant |

| Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) |

| II. Nerve cell origin |

| Neuroblastoma |

| Ganglioneuroma |

| Ganglioneuroblastoma |

| Pheochromocytoma |

| Chemodectoma |

| III. Nonneural origin |

| Lipofibromatous hamartoma |

| Intraneural lesions (lipoma, ganglion, hemangioma) |

| IV. Metastatic to peripheral nerve |

| V. Nonneoplastic origin |

| Traumatic neuroma |

Patients may complain of some degree of mild subjective sensory loss or paresthesias as a presenting sign of a schwannoma. Objective loss of function in the distribution of the affected nerve, however, is relatively rare. The extremely slow rate of growth, with subsequent gentle stretch and elongation of the involved fascicles, accounts for the relatively well-preserved neural function, even in the context of rather large tumors.

Schwannomas may arise from any nerve, including the peripheral portions of cranial nerves. They generally arise as solitary entities, but multiple schwannomas may occur in specific clinical scenarios. Neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) is a familial cancer syndrome, the classic diagnostic hallmark of which is bilateral vestibular schwannomas. These patients are also predisposed to multiple cranial, spinal, and peripheral schwannomas, as well as meningi. omas, neurofibromas, and gliomas. NF2 is an autosomal dominant condition caused by a mutation of the NF2 gene located on chromosome 22. This gene is a tumor suppressor gene, hence loss of function predisposes to tumor formation. The diagnostic criteria are outlined Table 49–2.

Recently, a group of individuals who harbor multiple schwannomas, but display none of the other features of NF2, has been identified. Population-based analysis has determined this group to be distinct from NF2 patients. The term schwannomatosis has been coined for this entity, and these patients typically have multiple spinal, peripheral nerve, or subcutaneous schwannomas, without bilateral acoustic schwannomas. The disease is limited to a specific body part (e.g., extremity) in about one third of cases. Preliminary genetic investigations suggest that at least a portion of schwannomatosis patients have a somatic mosaicism of the NF2 germline mutation. Inheritance is difficult to predict but is thought to be, in at least the vast majority of cases, sporadic.

| One of the following: |

| I. Bilateral vestibular schwannomas |

| II. First-degree relative with neurofibromatosis type 2 and a unilateral vestibular schwannoma, or two of the following: |

| i. Neurofibroma |

| ii. Meningioma |

| iii. Glioma |

| iv. Schwannoma |

| v. Posterior subcapsular lenticular opacity |

Malignant degeneration of schwannomas is a very rare occurrence, with only a handful of well-documented cases existing in the literature. Clinical features that should raise suspicion of malignant degeneration include greatly increased pain, rapid increase in tumor size, and sudden progressive loss of function along the distribution of the nerve. Further discussion of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNSTs) is found in Chapter 51 in this text.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

In this case the differential diagnosis is wide, encompassing the multitude of etiologies of nodular swelling in an extremity. In general, this includes infectious/inflammatory lesions, posttraumatic phenomena, vascular-related etiologies, as well as neoplastic entities. The differential diagnosis of neoplasia for this locale will include tumors of bone, soft tissue, and peripheral nerve. Often, specific features of the clinical history, findings on physical examination, as well as diagnostic investigations can help to identify the mass lesion as one intimately associated with a peripheral nerve. Armed with this knowledge, one can narrow the differential to a lesion of peripheral nerves. A classification scheme for peripheral nerve tumors is provided in Table 49–1. Peripheral nerve tumors are rare lesions, representing less than 5% of soft tissue tumors. They are not exclusive to the extremities and may develop at practically any location in the body, distal to the oligodendroglia-Schwann cell interface. The vast majority of peripheral nerve tumors are of nerve sheath origin, with schwannoma and neurofibroma composing the bulk of this subtype.

Diagnostic Tests

Diagnostic Tests

Diagnostic imaging studies are important in the investigation of a potential peripheral nerve neoplasm. Imaging studies often clearly define the relationship of a mass to a peripheral nerve and occasionally even offer insight into the specific pathology of the lesion. Unfortunately, as with their clinical features, the imaging characteristics of schwannoma and neurofibroma overlap greatly, making it impossible to definitively differentiate these two neural sheath tumors through diagnostic imaging alone.

The main imaging modalities that are used in the evaluation of peripheral nerve tumors are ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Plain roentgenograms are also valuable in the evaluation of peripheral nerve tumors, especially spinal schwannomas. Vertebral roentgenograms may show enlargement of intervertebral foramina or scalloping of vertebral bodies.

Ultrasound may be used to quickly and cost-effectively image peripheral nerve tumors. In general, ultrasound shows a well-defined mass with variable acoustic enhancement and a “ring sign” or echogenic ring lying within the tumor mass. Anecdotally, visualization of cavitation on ultrasound is felt to be more suggestive of schwannoma than neurofibroma. The CT appearance of a schwannoma is one of a hypodense, well-defined mass with often heterogeneous enhancement. This heterogeneous enhancement has been attributed to the different cellular density regions of the schwannoma, which will be discussed later. MRI is considered the imaging modality of choice. It gives superior resolution of the mass with respect to surrounding tissue and can often definitively identify the nerve of origin. On T1-weighted sequences schwannomas are usually of isointensity, although they have been occasionally reported as slightly hypo- or hyperintense. On T2-weighted sequences schwannomas are hyperintense and can sometimes display a “target sign,” or increased peripheral signal with a decreased central signal. With T1-weighted gadolinium-enhanced sequences, schwannomas also exhibit the target sign, thus showing heterogeneous enhancement.

As stated previously, no imaging modality is able to definitively differentiate schwannoma from neurofibroma. Although frank invasion of adjacent structures by a peripheral nerve tumor is highly suggestive of malignant histology, differentiation of a malignant lesion such as a neurogenic sarcoma from a benign schwannoma cannot reliably be made on radiological grounds alone.

Nerve conduction studies and electromyography are often performed in the diagnostic workup of peripheral nerve tumors. Such investigations do not, however, contribute salient information to the specific diagnostic decision-making process and, in fact, are often normal. There are no neurophysiological characteristics that differentiate among the peripheral nerve tumors. NCS/EMG do provide an objective measure of baseline nerve function in terms of clear electrophysiological parameters. Success (or failure) of definitive treatment can thus be assessed objectively. In this light, NCS/EMG can be viewed as an important preoperative investigation.

Management Options

Management Options

In the diagnostic investigation of a potential schwannoma there is essentially no role for needle-aspiration biopsy or partial open biopsy. These procedures run a high risk of inducing fascicular damage, and hence nerve dysfunction. Overall, operative results for patients that have undergone previous biopsy are much poorer than the comparable nonbiopsy group.

Surgical resection is the mainstay of therapy for schwannomas. However, it is reasonable to suggest that there is a subpopulation of schwannoma patients that do not require surgical intervention. Clear indications for resection include progressive neurological dysfunction, pain, and local mass effect symptoms. Relative operative indications include patient preference and cosmesis. Necessity of confirmatory tissue diagnosis is an operative indication in cases where the diagnostic workup fails to reveal features highly suggestive of schwannoma. Decision making with schwannomas can be difficult because little is clearly known about the natural history of these lesions. It does, however, appear clear that the risk of malignant degeneration is exceedingly remote. In addition, case series repeatedly suggest that outcomes are quite favorable for reduction of neurological dysfunction and pain after surgical resection. Data from these same series also suggest that the greater the preoperative nerve dysfunction, the less the return of nerve function postoperatively. Taking these points together, it becomes obvious that patients with nerve dysfunction, pain, or a less than clear schwannoma etiology for the mass should undergo resection. For asymptomatic patients presenting with a palpable mass and imaging that is highly suggestive of schwannoma, the course of action is less clear. Current knowledge would suggest that these patients could be treated conservatively and followed clinically without detriment, assuming the individual patient is comfortable with this option.

Surgical Treatment

Surgical Treatment

The operative principles for resection of schwannomas are applicable to all peripheral nerve tumors. The patient should be positioned and draped such that the distal musculature of the nerve of origin is easily visualized and accessible. General anesthesia is often used but should be planned such that neuromuscular blockade is not present. This allows use of intraoperative electrophysiological monitoring with motor stimulation and NAPs. These studies are fundamental to schwannoma resection. Incisions should be planned so that the nerve of origin is adequately exposed from the proximal to distal poles of the tumor. Prophylactic release of any common entrapment points adjacent to the resection site is advocated. An operating microscope, microsurgical instruments, use of micro-surgical techniques, and meticulous hemostasis are also required.

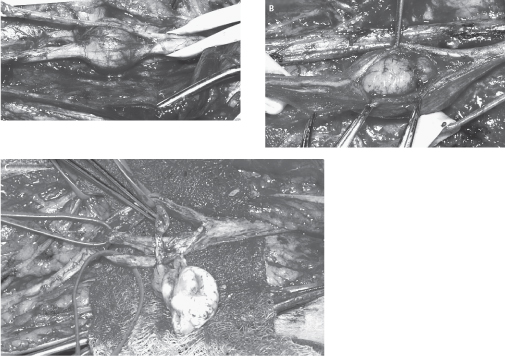

After identification of the nerve of origin, the tumor is exposed completely from proximal to distal poles (Fig. 49–1A). The nerve and tumor are isolated from adjacent soft tissue and vascular structures. Schwannomas have a yellowish color and an obvious tumor capsule. The fascicles of the involved nerve are observed to stretch over this capsule. Motor stimulation is then performed over the capsule of the tumor. This is important because it will identify intact fascicles that may not be readily apparent visually. When motor stimulation identifies an area of the tumor capsule with no active fascicles, dissection should begin there to expose a length of tumor (Fig. 49–1B). In almost all circumstances, a small fascicle can be found that is intricately involved with the schwannoma and is noted to enter the proximal pole and exit the distal pole (Fig. 49–1C). Electro-physiological studies invariably show such a fascicle to be nonfunctioning. At this point NAPs should be performed across the schwannoma to determine the presence of conduction abnormalities preexcision. The generally accepted approach to excision is one of microsurgical extracapsular excision with gentle dissection of the capsule away from the active nerve fascicles. The vascular pedicle is usually at the proximal pole, and dissection and bipolar coagulation of this structure in combination with nonfunctioning fascicles facilitate removal of the schwannoma. Occasionally, as in schwannomas of the lumbosacral or brachial plexus, the tumor may be too large to be removed in an extracapsular fashion. In such cases, internal debulking of the tumor will aid the resection. An ultrasonic aspiration device is ideal for such intracapsular debulking. Given the extrafascicular nature of schwannomas cable grafting of the nerve across the tumor resection site is exceedingly uncommon. In histologically proven schwannomas in which a functional fascicle cannot be readily dissected from the tumor, it is more prudent to leave residual tumor mass than chance postoperative deficit. On the occasion that postexcision NAPs are grossly abnormal secondary to inadvertent excision of a functionally relevant fascicle, nerve grafting can be performed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree