Sleep disorders and fatigue are clinically relevant problems that are increasingly recognized as an integral part of Parkinson’s disease (PD). The interest in these topics is attested by the large number of indexed publications in the last 15 years, which in the area of sleep was fueled by two studies: the description of “sleep attacks” induced by dopaminergic agonists (1) and the recognition that an isolated sleep problem—dream enactment behaviors—may herald the development of PD by years (2). As a result, a lot has been learned, although many unresolved issues still remain.

SLEEP DISORDERS IN PD

For many years, insomnia was considered the main relevant sleep problem in PD (3). Daytime sleepiness was thought to be rare, more likely a side effect of anxiolytics or poor sleep, and levodopa-induced sleepiness “a well recognized but uncommon phenomenon” (4). On the other hand, altered dream events and behaviors were considered mainly features of L-dopa–induced psychosis not occurring in the pre-L-dopa era (5). This notion of sleep disorders in PD has changed, and new findings have led to a different perspective.

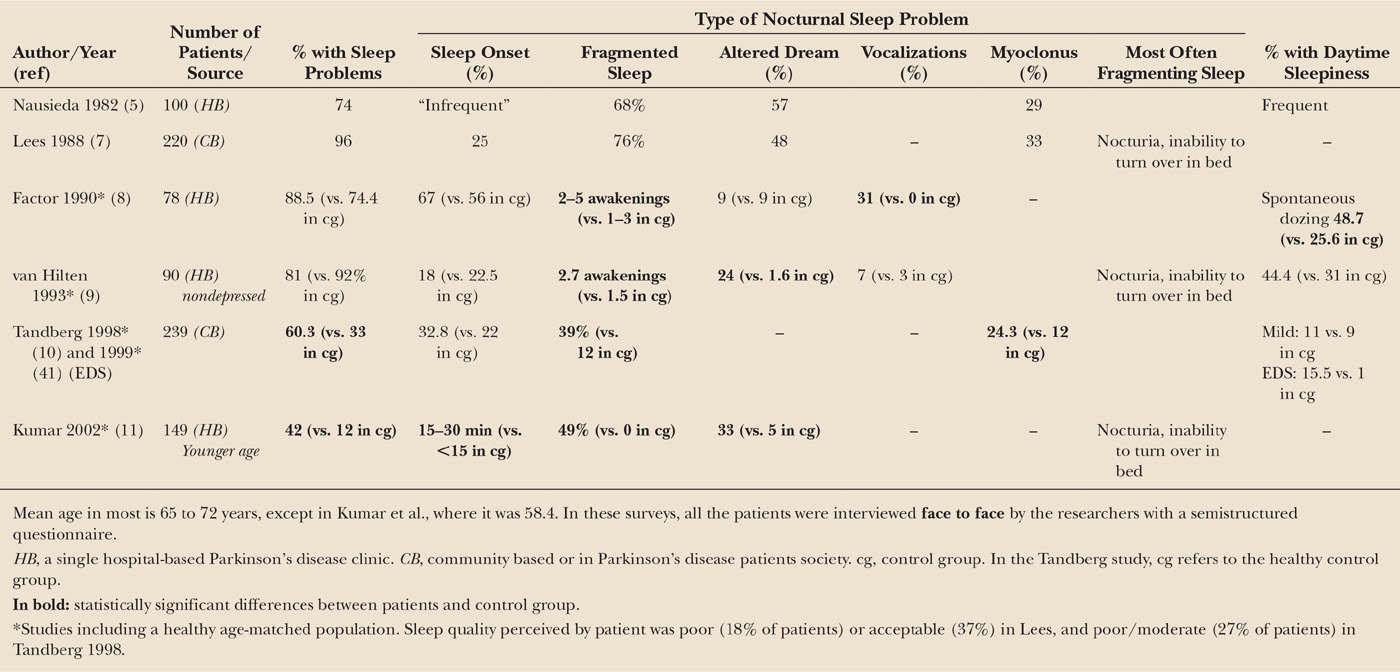

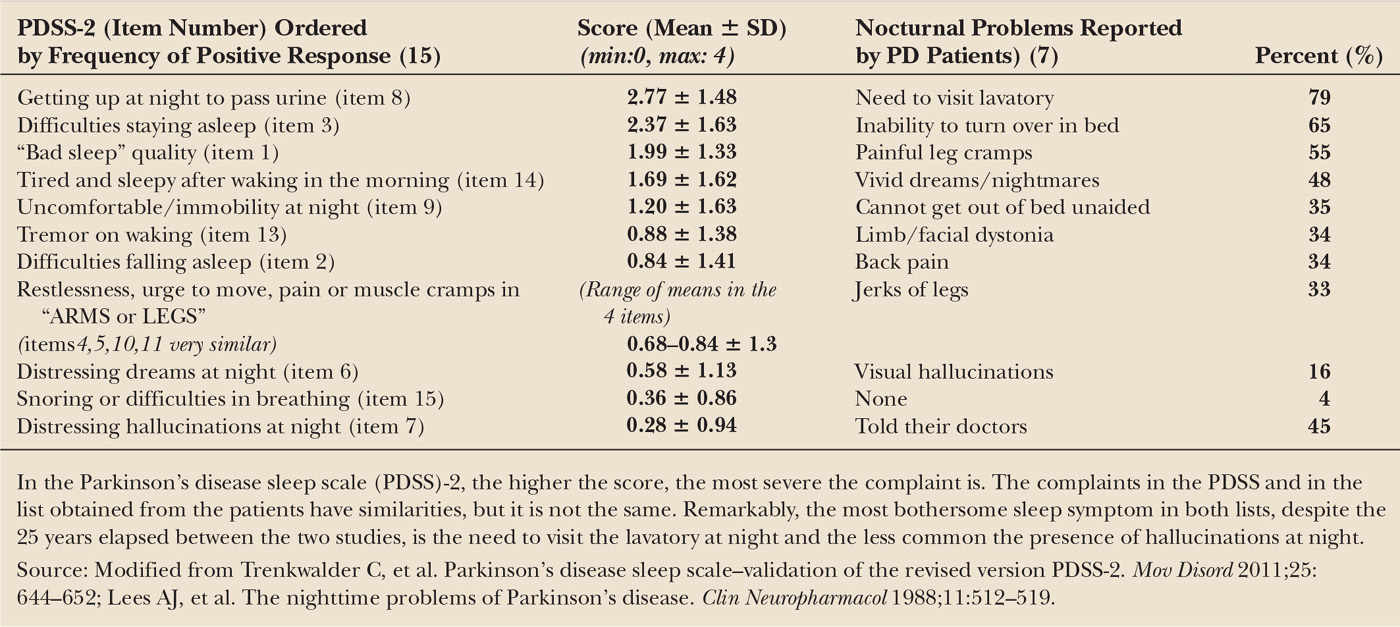

Much of the initial research looking at sleep in PD derived from polysomnographic (PSG) studies performed in specialized centers in a few patients (3,6). This approach resulted in a partial view of the problem. Surveys more focused on the clinical complaints of the patients (5,7) found a surprisingly high number of PD patients with sleep complaints. Because aging, mood disorders, medications, and physical disability that frequently occur in PD alter sleep, subsequent surveys (8–11) incorporated healthy aged controls or patients with other chronic disorders (10) (Table 41.1). Two such studies (10–11) reported a 2 to 3.5 times higher prevalence of sleep disorders in PD patients than in healthy controls, and 1.5 times higher than in a chronic disease (10), and two others (8,9) showed a high prevalence both in PD patients and controls. Fragmentation of sleep was reported as a relevant problem in all the studies in contrast to sleep-onset difficulties, which were almost similar than in controls. In five of five studies (see Table 41.1), patients also reported altered dreams with or without vocalizations, and in three in which it was asked, excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) (5,8,9), although those findings did not have much impact at that time. The most frequent causes of nighttime awakenings were nocturia and inability to turn over in bed. Overall, these problems produced a poor to moderate sleep quality in approximately a fifth of patients. In general, patients obtaining continuous sleep reported a “good” quality of nighttime sleep, whereas most with fragmented sleep described their sleep as “poor” (7). These investigations were performed in PD patients with moderate disease severity. Nothing much is known about what happens in patients with advanced disease due to the difficulties in assessing their sleep/wake patterns (12,13).

CLINICAL FEATURES OF SLEEP DISORDERS

There are many known sleep disorders (14), but their main symptoms can be reduced to three: inability to sleep as well as desired (insomnia), abnormal behaviors and events during or around sleep (parasomnias), and EDS. In PD, all three types of problems can occur, alone or in combination. Disentangling the sleep symptoms from the motor, sensory, and mood effects of the disease or its treatments is often complex, making this area one of the most difficult in sleep medicine.

Insomnia

Insomnia refers to a difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep that results in general sleep dissatisfaction. This occurs despite an adequate time opportunity and circumstances for sleep and is associated with some form of daytime dysfunction, such as decreased mood, irritability, cognitive impairment, or fatigue (14). Insomnia is one of the most frequent sleep complaints in the general population, with its prevalence increasing with age. It may occur alone or accompany comorbid mental or medical illnesses. Several studies (5,7–11,15) have found (Tables 41.1 and 41.2) that in patients with PD fragmented sleep—that is, waking up several times during the night with difficulty returning to sleep or having a final awakening occurring too early—is a frequent and bothersome problem, whereas difficulties in sleep initiation occur no more often than in the healthy aged population. In the early phases of PD, however, there are little differences in sleep with healthy controls (16–18), suggesting that sleep deteriorates with time. Damage to brain areas regulating sleep by the neurodegenerative process is often implicated in the pathogenesis of insomnia in PD, but this hypothesis has not been proven. An 8-year longitudinal study of a cohort of 231 patients with PD (19) with a mean age of 73 years and a mean disease duration of 9 years at baseline showed a prevalence of insomnia (defined as sleep fragmentation, difficulties in falling asleep, waking up too early, or using hypnotic pills) of 59%. Four years later, it was 53.5%, and a similar figure (56.2%) was found after 4 more years of follow-up. Interestingly, the patients affected by the problem at each follow-up visit were different, that is, insomnia disappeared in some patients but appeared in others who did not have it previously. Factors associated with insomnia were different at each follow-up visit and included disease duration, female gender, or mental depression. In patients with parkinsonism associated with synuclein mutations (20), however, intrinsic mechanisms could probably be responsible for the insomnia detected early in the disease in mildly affected, untreated patients.

Insomnia is diagnosed by clinical history with the patient, but the bed partner may also help, especially in patients with cognitive impairment. “I cannot sleep” or “I have insomnia” are not good enough descriptions of the problem. One needs to learn if the problem is in falling sleep only, in maintaining sleep continuity, in waking up too early, or in a combination of the above problems and try then to find its possible origin. The causes typically associated with difficulties in sleep initiation and sleep maintenance are shown in Tables 41.3 and 41.4 (21). These include mainly disease-related and medication-induced problems but also sleep disorders that occur in the general population.

| List of Causes Disturbing Sleep Initiation in PD |

Not sleepy when lights go off

Nursing home, early bedtime

Caretaker, early bedtime

Out of phase with spouse, family

Daytime naps

Medication effect

Stimulants—selegiline, amantadine, caffeine; SSRI antidepressants

Discomfort

Cannot find comfortable position

Painful leg cramps, back pain

Off period

Restless legs syndrome

Akathisia

Nonmotor fluctuations

Annoying tremor

Depression/anxiety

Illusions, delusions, hallucinations

Source: Modified from Friedman JH, Chou KL. Sleep and fatigue in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2004;10:S27–S35.

| List of Causes Disturbing Sleep Continuity in PD |

Nocturia

Anxiety

Depression

Sleep breathing disorder

Reappearance of tremor during awakenings

Periodic leg movements

Inability to turn over/difficulty getting in/out of bed

Medication effects (alcohol, excessive dopaminergic therapy, stimulants)

REM sleep behavior disorder (vocalizations, nightmares, dream enacting)

Source: Modified from Friedman JH, Chou KL. Sleep and fatigue in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2004;10:S27–S35.

Sleep-onset insomnia in PD may result from anxiety and depression, which are quite common in PD (22,23), from worsening of the motor symptoms in the evening or from use of selegiline or amantadine in the night due to its alerting effects. In mildly affected patients, excessive dopaminergic treatment appears to disrupt sleep (measured actigraphically) in a dose-dependent effect (24). In patients with advanced PD with reduced physical activity and ample opportunities for daytime napping, lack of sleepiness at night may also relate with sleeping too much during the day.

Restless legs syndrome (RLS) may also occur in PD and, if severe enough, will make sleep onset or maintenance impossible. The four essential diagnostic criteria for RLS are [1] an urge to move the legs accompanied by unpleasant leg sensations, [2] worsening during periods of inactivity, [3] improvement with movement, and [4] worsening in the evening or at night. A fifth criteria was added recently (25) demanding the careful consideration and exclusion of mimicking conditions. Akathisia is one of such conditions, which also affects a number of PD patients. Akathisia may be differentiated from RLS by the lack of unpleasant leg sensations and of worsening at night. However, there is some overlap between the two conditions (26) and the distinction is not always neat. The supportive criteria for the diagnosis of idiopathic RLS, that is, a family history of the problem, response to dopaminergic therapy, and periodic leg movements during sleep, are less useful in PD because family history of RLS is less common in PD; almost all PD patients are on dopaminergic medication already, and PLMS often occur unrelated to RLS symptoms (27). An additional problem is the presence of sensory symptoms involving the legs or other body areas (28) that may respond to L-dopa and may resemble symptoms of RLS. In fact, well-defined RLS has been described in patients during the off period (29,30). This is an area that needs further exploration. Studies on the prevalence of RLS in PD have reported percentages ranging from 0% to 50%, although the most common figure in these is about 15% to 20% (30–34).

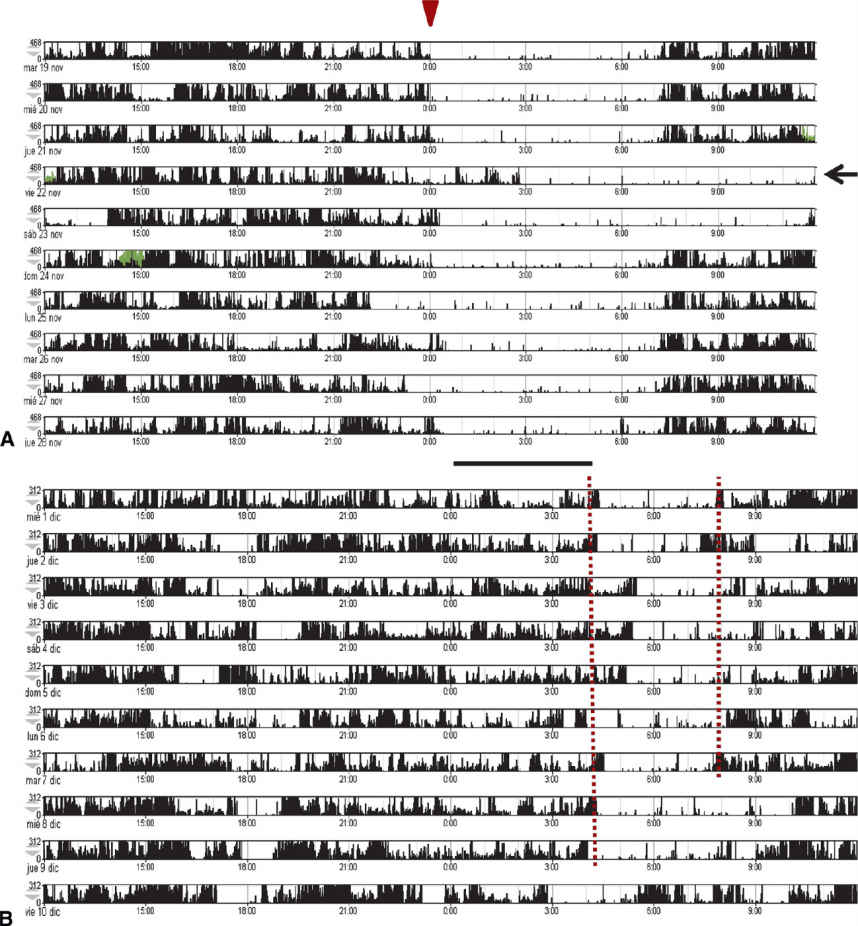

The causes of sleep fragmentation are displayed in Table 41.4. The two most common are nocturia and inability to turn over in bed. Nocturia in PD relates to a hyperactivity of the detrusor muscle of the bladder, causing voiding dysfunction. It is associated with higher motor severity and a shorter sleep duration (35) but not with dosage of dopaminergic drugs. Motor difficulties associated with getting out of bed and a long time to return to sleep after nocturia are the reasons that bother the patients the most. Inability to turn over in bed (axial bradykinesia) is another very common complaint that increases in frequency over time (19). It results from lower levels of dopamine agents during the night. Also, parkinsonian tremor, which typically resolves on falling asleep (36), may recur during awakenings in the middle of the night and disturb sleep reinitiation. Early morning awakening occurs in about a fifth of PD patients (19) (Fig. 41.1). Mental depression is often, but no always, associated with early morning awakening.

Other problems, unrelated to PD, but common in the general population, may also break sleep continuity in PD patients. Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is clinically characterized by snoring and repeated breathing pauses during sleep, which are associated to EDS and fatigue. Sleep apnea, documented with PSG, may occur in about a fifth of PD patients with a frequency reportedly lower, equal, or higher than in the general elderly population (37–39). If OSA is present, however, treatment with a continuous positive airway pressure device (CPAP) may be equally effective in PD patients, and should be tried.

Periodic limb movements of sleep (PLMS) are stereotyped movements of the foot and leg typically recurring every 20 to 40 seconds, mainly during the first part of the night, during non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep. They occur in more than 80% of patients with RLS, but they have been described also in well-established PD, even in the absence of RLS (27) much more often than in controls. PLMS are less frequent in de novo PD and increase with progression of the disease or its treatment (26). PLMS may vary in intensity: from being a subclinical finding to disturbed sleep continuity of the patient and bed partner. Although usually mentioned as another reason for sleep disruption in PD, its clinical significance in PD and in the nonparkinsonian population is still unclear.

Excessive Daytime Sleepiness

Sleepiness is a universal experience that signals the proximity of sleep. The closer the sleep onset is, the stronger the feeling of sleepiness. This is a normal phenomenon clinically associated with typical signs such as yawning, closing of the eyelids, motor slowing, or lapses in attention. Sleepiness is excessive when interferes with daytime activities and leads to sleep in unusual or dangerous situations, such as working or driving. Clinically indistinguishable sleepiness results from many different causes, which include sleep deprivation, central nervous system hypersomnias, medications, or fragmented sleep as in OSA (40). This is why finding the cause (or causes) of sleepiness is so difficult. In PD, the frequency of excessive sleepiness is considerable, ranging between 15% and 71% of patients or between 1.5 and 15 times found in healthy controls (41–47). Despite its frequency, EDS does not rank high in the list of most bothersome symptoms, according to the patients’ own view (48).

EDS is assessed by interviewing the patient and spouse/caretaker about problematic daytime sleepiness, determining if it appears only in passive, relaxed situations—where it would more tolerable—or also during active situations, such as standing, working, driving, or talking, suggesting a more severe problem. It is important to clarify if the patient feels sleepy before falling asleep, if he/she falls asleep without warning signs of sleepiness or if he/she feels it but not for enough time to take preventive measures. The majority of PD patients (46) perceive symptoms of sleepiness before sleep, but some describe awakening from a sleep episode without remembering any preceding sleepiness, what is called a “sleep attack.” The reported frequency of sleep attacks in PD varies a great deal, from 0.8% (49), 3.8% (46), 13.9% (44), 20% (50), 22.6% (51), or 30.5% (52), in part due to the different ways of assessing this symptom (autoadministered mailed questionnaires, telephone interviews, or face-to-face clinical encounters). Some healthy controls and a few untreated PD patients (3%) (50) report also sleep attacks. One problem with these studies is that a substantial percentage of patients reporting sudden episodes of sleep or claiming not having warning signs in questionnaires (50,53) changed their mind after detailed questioning. The term “sleep attack” suggests that the patient has a “seizure-like” episode of sleep that goes from “100”—fully awake—to “0”—asleep—instantaneously. By clinical history, however, sleep “attacks” occur mostly on a background of continuous sleepiness, especially in situations of minimal or moderate physical activity (34,46), although some patients report them during eating, talking, or writing (50). A surprising fact is that despite their apparently high frequency in surveys only a very few patients have had PSG recorded during the episodes (54,55) and the results do not allow to make any definitive conclusion as to their differential clinical characteristics. In other sleep disorders, such as narcolepsy, however, falling asleep without the patient reporting any warning signs is associated with visible signs of typical sleepiness. A misperception of these signs could be the reason why PD patients do not take preventive measures (56). It follows that driving alone, for example, may be dangerous in this setting (57), whereas an accompanying person aware of the problem could detect the episodes with enough time to stop the car.

Patients reporting sleep attacks often have abnormal values on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), suggesting that it could be used to detect patients at risk (46), but this is not the case for all the patients (50). In addition, different cutoff values of the ESS have been proposed to identify patients at risk: 7 in one study (46), a surprisingly low value which is considered normal in many studies, or 10 in several others (50). Using objective measures of sleepiness (58) has shown that abnormal levels of physiologic sleepiness may not be detected with the ESS.

Figure 41.1. Self-imposed late onset of sleep to prevent early morning awakening, as recorded with actigraphy. (A) Actigraphic recording during 10 consecutive days in a healthy subject. Dark areas represent motor activity recorded every minute at the nondominant wrist. Inactivity starts regularly, at midnight (arrowhead at the top) except on Friday night (horizontal arrow), and ends regularly at 7:30 AM except on Saturday and Sunday. Inactivity periods normally correspond to sleep. Small numbers mark the hour of the day. (B) Actigraphic recording during 10 consecutive days in a PD patient complaining of sleepiness. Inactivity starts irregularly between 3 AM and 5 AM and ends irregularly at 8 AM to 9 AM (vertical lines). This delay was self-imposed by the patient, to avoid the frustrating early morning awakenings (around 3 AM) that she suffered when going to sleep at midnight. To achieve this goal, she sat down in a kitchen chair, dozing off repeatedly, until 3 AM to 5 AM (bar), and went then to bed, falling asleep immediately during 3 to 4 hours.

Mechanisms of sleepiness in pd Sleepiness in PD may have many causes, and in a single patient, one or several may occur at the same time. Three main causes have been implicated: involvement of sleep/wake systems by the disease process, side effect of the dopaminergic treatment, and poor nighttime sleep.

Evidence supporting a progressive alteration in sleep/wake systems is based on the results of an 8-year longitudinal study of the development of EDS in 232 PD patients in Norway (59). At baseline, EDS was present in 5.6% of the sample, 4 years later in 22.5% of the available patients, and 4 years later in 40.8%. In the majority, it was a persistent feature, with new patients incorporating the symptom at each new evaluation. Age, male gender, and use of dopamine agonists were the factors related with EDS. In a subgroup of patients never treated with dopamine agonists, however, sleepiness increased at almost the same pace over the 8-year period, and this was related with age and Hoehn and Yahr stage. The presence of insomnia, abnormal behaviors, and movements during sleep as measured by questionnaire did not relate with EDS either. Cognitive impairment was not associated with EDS in this study, although in others it was a relevant factor (13,60). On the other hand, several studies found the prevalence of EDS in early untreated PD patients similar to that in age-matched healthy controls (43,61). Therefore, it appears that a combination of age and intrinsic changes in brain areas regulating sleep could induce or predispose to the emergence of EDS in PD (59). The detection of sleep-onset REM (SOREM) periods and short sleep latencies in the Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT) of a number of sleepy PD patients, as typically seen in narcolepsy, raised speculation about a possible narcoleptic pathology in PD patients with EDS (62,63). SOREM episodes and short sleep latencies in the MSLT, however, have been shown not to be specific for narcolepsy in recent studies as they can be recorded in healthy subjects with irregular sleep schedules, sleep deprivation, or intake of antidepressants (64), factors that were not controlled in the above-mentioned studies.

Research on biologic markers related to sleepiness, such as hypocretin/orexin has not been conclusive. Whereas hypocretin neuron cell counts in the brains of advanced PD patients show a mild to moderate (up to 40%) reduction, much less severe than in narcolepsy (65,66), CSF hypocretin levels are normal (13,67,68). In contrast to narcolepsy, however, in PD other hypothalamic neurons with sleep-inducing properties, such as the Melanin concentrating hormone (MCH)neurons, are also reduced in number (65,66), making it difficult to know the net result of these changes with seemingly opposite actions on sleep. A moderate correlation between CSF hypocretin levels and MSLT latencies has, however, been recently reported, possibly implicating this neurotransmitter in the pathogenesis of EDS in PD (69). Finally, another possible mechanism contributing to EDS in PD patients is the recent finding of a decrease in the amplitude of the circadian oscillation of the melatonin rhythm related with the ESS score (70).

Evidence supporting a role for dopaminergic drugs in EDS rests in the observation that pramipexole, ropinirole, and L-dopa have all been shown to induce sleepiness in healthy subjects (71–73). In patients with PD, IV L-dopa also induces sleep in selected patients (74), and sleepiness was also reported as a side effect in the trials with dopamine agonists, particularly with higher doses of the compounds (57). The mechanisms of this action are not completely understood. In experimental studies, sleepiness appears with low doses of the dopaminergic agent, due to a presynaptic autoreceptor effect, whereas alertness is induced by high doses, as a postsynaptic effect (72). This is in contrast with the experience of patients with PD, where more sleepiness occurs with higher doses of dopamine agonists (1,57). A few studies (43,57) have examined untreated early PD patients before and a few months after institution of dopaminergic treatment. At baseline sleepiness was similar to a control population, but after several months of dopaminergic treatment, EDS was for the first time apparent. This happened despite an improvement in motor symptoms and with little change in the PSG measured nocturnal sleep parameters, (75) supporting a primary sedative role of dopaminergic agents. This effect is probably stronger with dopamine agonists (all the different types) than with L-dopa (50,59,76).

Finally, the other mechanism implicated in the origin of sleepiness in PD is sleep fragmentation with shortening of nocturnal sleep time, either as a result of disease-related problems (motor symptoms, pain, apnea, nocturia, depression), as a side effect of the treatments, or as a result of neurodegeneration of intrinsic sleep systems. In studies using subjective measures of sleepiness, however, the degree of nocturnal sleep disruption (measured also subjectively) does not seem to be related to EDS (59), whereas in studies using objective measures of sleepiness (such as the MSLT, or the Maintenance of Wakefulness Test—MWT), both a correlation and lack of correlation between nocturnal sleep measures and daytime sleepiness has been reported (58,63,77,78). Although several reasons may account for these results, methodology is an important one. The two studies using the MWT (58,78), a sensitive measure of the resistance to fall asleep, in PD patients free of hypnotics and antidepressants, found that the degree of sleep fragmentation relates with impairment of daytime alertness.

It is very likely that combinations of the above three factors will eventually be responsible for sleepiness in a given patient, with a final addition of the soporific effects of each of the different factors.

An unexpected finding is the observation that EDS may also be a risk factor for developing PD. Two epidemiologic studies have suggested that “being sleepy most of the day” (79) or a higher number of daytime napping hours (80) in asymptomatic elderly men increases their risk of developing PD even when adjusted for features like insomnia, depression, coffee drinking, or cigarette smoking. This is difficult to reconcile, however, with the clinical experience that EDS is uncommon in early PD (17,23,75).

Parasomnias

Parasomnias are unusual phenomena occurring either during the entry into sleep, during sleep itself, or during arousals from sleep (14) with a display of complex movements, behaviors, vocalizations, or emotions. Two main groups of parasomnias are recognized: NREM sleep parasomnias, including sleepwalking, sleep terrors, and confusional arousals and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep parasomnias, represented mainly by REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD).

In early studies of sleep in PD, abnormal dream events and vocalizations (5,9), or myoclonus, “flinging arm or leg movements” and “sleep walking episodes” were already reported (5). Interestingly, these episodes were thought to occur during NREM (slow wave) sleep (5), although examples of the sleep recordings were not shown. After the identification of RBD (81), this parasomnia is considered the most frequent cause of abnormal sleep behaviors in PD, and NREM parasomnias are very rare events.

REM Sleep Behavior Disorder Clinically, RBD is characterized by recurrent episodes of vigorous, jerky, discontinuous movements, and vocalizations during sleep, looking to an observer as if the patients were enacting their dreams. This impression is frequently confirmed on awakening the patient during the episode. Most reported dreams are unpleasant, with a negative emotional content, with the patient arguing or fighting against an imaginary offender, but nonviolent dreams and behaviors are also seen. In the most severe form of RBD, patients may fall out of bed, injure themselves or their bed partner with the result of fractures, lacerations, or contusions of diverse importance. In milder forms of RBD, the patient may not even mention the sleep problems to the physician if not specifically asked, and patients sleeping alone may not be aware of the problem (81). Less often, RBD episodes lack the typical discontinuity in the movements becoming difficult to differentiate them from awake movements. When recorded with PSG, these behaviors occur only during REM sleep and are associated with abnormally increased EMG activity in the mentalis muscle and limbs, instead of the physiologic muscle inactivity (atonia) typical of REM sleep (81,82). RBD may be idiopathic, without any other discernible neurologic alteration, and secondary, in patients who already have a known neurologic disease, typically PD, dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and multiple system atrophy (MSA), and less commonly narcolepsy or spinocerebellar atrophy. RBD can also be associated with the intake of antidepressants, β-blockers, or alcohol deprivation (81), and in the presence of these substances, the diagnosis of idiopathic RBD is less reliable. Patients with idiopathic RBD are most often male and older than 50 years, but this may differ slightly in patients with secondary RBD (83).

One of the major discoveries in sleep medicine was the observation that the idiopathic form of RBD is followed years later by a neurodegenerative disorder (2,84,85) (estimated risk from diagnosis of RBD of 35% at 5 years, 73% at 10 years, and 92% at 14 years), mainly PD and DLB and less frequently MSA (82). The reason of this preference for synucleinopathies is probably because of their significant impairment of brain stem areas implicated in REM sleep generation. Type of dreams and motor and vocal expressions of RBD are similar between subjects with IRBD and secondary RBD to MSA and PD (83). Table 41.5 shows the criteria for diagnosis of RBD according to the recent edition of International Classification of Sleep Disorders, which now demand the recording of a PSG (14)

| Diagnostic Criteria of REM Sleep Behavior Disorder (ICSD III) |

• Repeated episodes of sleep-related vocalization and/or complex motor behaviors—by history or by observing these episodes during a single night of video PSG. The episodes correlate with dreams, leading to the report of “acting out one’s dreams.” Upon awakening, the individual is awake, alert, coherent, and oriented.

• The behaviors are documented by PSG to occur during REM sleep or, based on the clinical history, are presumed to occur during REM sleep.

• PSG recording demonstrates REM sleep without atonia (RWA)—using 30-second epoch scoring guidelines.

• On occasion, patients may have a typical clinical history of RBD (with dream-enacting behaviors) and typical RBD behaviors during video PSG but (1) without sufficient RWA to satisfy PSG criteria, or (2) may not have a video PSG recording readily available. Such patients may be provisionally diagnosed with RBD, based on clinical judgment.

• The disturbance is not better explained by another sleep disorder, mental disorder, medication, or substance use.