Chapter 72 Sleep Problems in First Responders and the Military

Abstract

Police officers in the United States, Canada, and many other industrialized nations often are overly fatigued because of long and erratic work hours, shift work, and insufficient sleep. These factors likely contribute to elevated levels of morbidity and mortality, psychological disorders, and family dysfunction observed among police. Fatigue-related impairments to officer performance and decision-making can generate unexpected social and economic costs because of the sensitivity, risks, and potential consequences of their actions.1

Prevalence of Sleep Loss, Mortality, and Morbidity

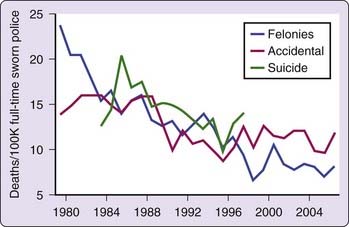

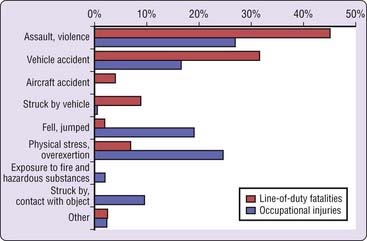

Officers whose sleep is chronically disrupted by personal characteristics, off-duty choices, or employer scheduling and work-hour practices suffer from disproportionately high levels of cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and metabolic diseases; chronic insomnia, sleep apnea, and other sleep disorders; and psychological disorders, depression, suicide, and family dysfunction.2–11 Research linking long and erratic work hours to these sorts of disorders is substantial and compelling.1,12 Shorter-term links between sleep loss and the sorts of on-the-job accidents and injuries that most frequently kill or seriously harm police officers also are well documented1,12,13 Figures 72-1 and 72-2 show the sources of on-the-job injury and death for police officers.

Figure 72-1 Police officers killed per capita in the United States, by cause.

(Felonies and accidents from FBI, LEOKA data, 1980-2007; suicides from CDC, NOMS data, 1984-1998.)

Figure 72-2 Causes of police injuries and fatalities in which work time was lost.

(National Law Enforcement Officer Memorial Fund, 1995-2002.)

In Figure 72-1, note that felonious killings of police officers have declined steadily during the past 27 years, likely as a consequence of improvements in training, tactics, and soft body armor. Accidents tend to account for a larger proportion of officer deaths than do felonies, and accidents are largely dominated by nonfelonious vehicular accidents. Accidents have declined much less during this period despite major improvements in vehicle safety, such as crash-resistant designs, air bags, shoulder harnesses, radial tires, antilock braking systems, and disk brakes. Reported suicide rates, which are available only from 1984 to 1998,14 tend to account for slightly more officer deaths annually than either felonious killing or accidents. However, suicide deaths are systematically underreported because cultural and economic incentives produce a substantial bias for full reporting of felony and accidental deaths and against full reporting of officer suicides.

Figure 72-2 illustrates common causes of police on-the-job fatalities as well as injuries that were sufficiently serious to require lost work time. Note that both tend to be dominated by accidents of the sort that are made more hazardous by sleep loss and disruption15–17 as well as circadian factors, which accidents track closely.13,18

Despite this evidence, police in the United States and Canada continue to compound the unavoidable physical insults of shift work with large amounts of overtime.19–21 Most officers assigned to patrol and detective assignments will at times work 16 or more consecutive hours and sometimes more than 24 hours straight. As with most occupations, a small proportion of the officers in most departments work a large proportion of the overtime. Extreme examples of officers working more than 3000 hours of overtime per year have been reported regularly during the past decade.22 On top of these practices, many officers also work second jobs, about which almost no hard data are available.

The burden borne by officers and their families as a consequence of work-hour practices is similar to that of other occupational groups.1 However, unlike occupations in which shift work and long, erratic work hours tend to be limited to the first few years of one’s career, police and many first responders often work while sleep deprived throughout their careers. Moreover, they do so in highly unstructured, variable, risky, and unpredictable situations that require both expert judgment and decision-making and great self-restraint. After chairing a congressional panel on the impact of sleep on society, here’s how Dr. William C. Dement, one of the most distinguished figures in sleep medicine, summarized this issue20:

Implications for Other First Responders and the Military

The police may be seen as a model occupational group for understanding the impact of sleep loss on other first responders such as firefighters and field emergency medical personnel.23 This model also is increasingly applicable to military operational environments that involve small ground units rather than massed armies, navies, and air forces. The challenges of new operational roles such as such as those faced by small infantry units involved in urban counterinsurgency patrols and roadblocks, peacekeeping, and nation building are more akin to police work than traditional infantry combat.24 As in police work, the tactical and strategic success of these endeavors requires an exquisite balance between the use of aggression and restraint.25–28 Success often hinges on the performance of low-ranking infantry and security personnel operating in small, relatively autonomous units. These troops often must make difficult and complex decisions about the use of deadly force in fluid, ambiguous, and emotionally charged situations. To be effective, they must find and neutralize enemies who are embedded within the general civilian population without alienating that population. This means that they must build strong relationships with local people by fostering public perceptions of their civility and professionalism as well as the justice and fairness of their actions, even as they do things that are intrusive and unpleasant for the individuals they delay, confront, or detain. Failure to strike an effective balance between aggression and restraint in these challenging tactical situations can carry deadly consequences for troops on the ground and for the public they are attempting to win over. It also can lead to serious tactical, operational, and even strategic setbacks.

Performance Challenges and Sleep Loss

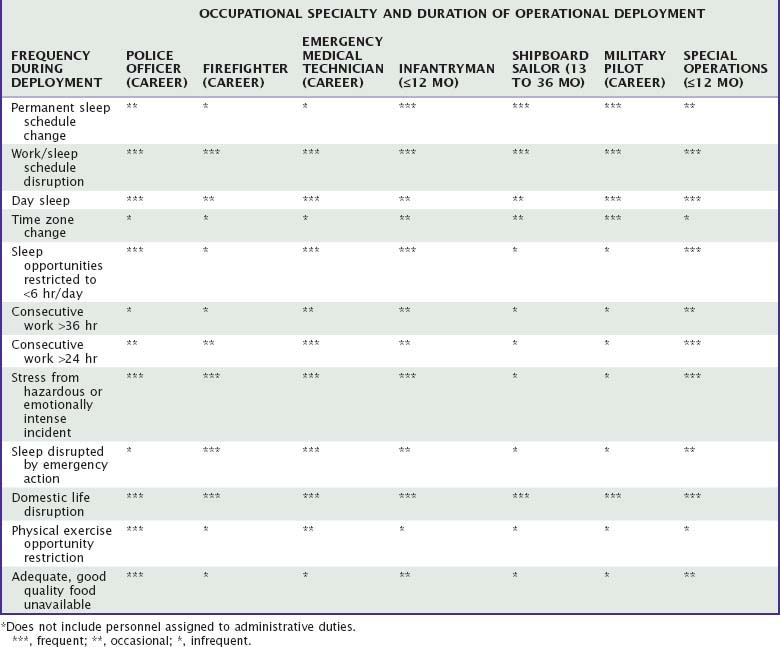

Sleep loss degrades the ability of first responders and many military occupational specialties to respond to the challenges they face in operational environments. The immediate effects of sleep-related performance decrements increase risks of death or serious injury to operators, their peers, and bystanders whom they encounter. Longer-term health risks for these occupational groups are a function of the duration and frequency of exposure. Table 72-1 provides examples of the typical duration of operational deployments and the typical frequency of sleep-related insults and hazards in operational settings among selected first responder and military occupational specialties. Note how some occupational groups’ exposure to sleep-loss–related risk factors are much more episodic whereas others face many of the same challenges throughout their careers. Although space limitations preclude a detailed discussion of the specific consequences of sleep loss for each occupational group, the discussion that follows illustrates the immediate and long-term consequences of sleep loss on police officers. Those same consequences may be extrapolated to other first responders and military specialties as long as the frequency and duration of exposure are taken into account.

Table 72-1 Illustrative Examples of Typical Duration of Operational Deployments and Frequency of Sleep-Related Insults and Hazards in Operational Settings among Selected First Responder and Military Occupational Specialties*

Many laboratory studies confirm that sleep loss affects a broad range of skills associated with decision-making, including insight, risk assessment, innovation, communication, and mood control.29 In fact, brain imaging studies demonstrate that lack of sleep has a disproportionate effect on the prefrontal cortex—the “executive” region of the brain where problems are solved and prioritized according to moral and situational criteria and where consequences are considered and responses are planned and coordinated.12 This suggests that even though tired cops may still be able to perceive a great deal about a situation because some parts of their brains are functioning well, they will be less likely to make sound decisions about what to do. Recent studies also suggest that they may be more likely to make hasty moral decisions and engage in riskier behavior.30,31

Decision-Making

Chronic sleep loss reduces the ability to think clearly, handle complex cognitive tasks, and solve problems.12,32 Basic skills (e.g., marksmanship, emergency driving, and routine enforcement or public safety activities) rely heavily on abilities acquired through rote training, repetition to ingrained automatic responses, or unhurried rational-analytic approaches to choosing from among alternative courses of action. These basic skills clearly tend to be degraded by sleep loss.33–35 However, the impact of sleep loss is likely to be even greater on the highly nuanced skills and expertise that police officers and similar occupations employ in emergency situations. Emergency responses in stressful, rapidly evolving and complex situations characterized by ambiguity, high risk, and personal threat require great expertise to avoid catastrophic outcomes36–38 and to apply complex rules of engagement quickly in complex and volatile naturalistic settings.39,40 Sleep loss degrades both routine decision-making skills and the ability to apply expertise in critical field situations, and it also diminishes critical abilities to modulate mood and arousal, especially in highly emotional confrontations and when being assaulted.41–45

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree