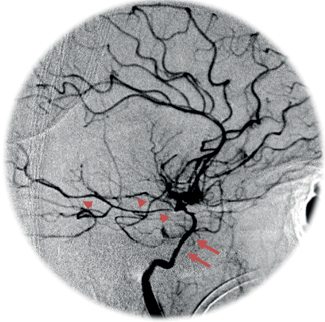

52 What is the most common cause of SAH? Trauma. SAH occurs in 12 to 53% of all head injury cases.1 Ruptured intracranial aneurysms are the most common cause of spontaneous (nontraumatic) SAH.2 How may SAH be diagnosed? Symptoms: Sudden onset of severe (thunderclap) headache with or without nausea, vomiting, syncope, meningismus, photophobia, coma, seizures, ocular hemorrhage Radiographically: Noncontrast high-resolution head CT detects almost all cases (>90%) of SAH within 48 hours of bleeding.3,4 Lumbar puncture: The most sensitive test for SAH.5,6 Often ordered only if CT is negative but high clinical suspicion for SAH remains. A low risk of rebleeding exists with lumbar puncture. What are the characteristic findings of SAH on lumbar puncture? Elevated opening pressure, xanthochromic (yellow-appearing) supernatant (seen in almost all cases of SAH by 12 hours), elevated RBC count (usually greater than 100,000), elevated protein, RBC:WBC ratio >700:1 (rules out traumatic tap) What is the risk of rebleeding after aneurysmal SAH if the aneurysm is not treated? • 15 to 20% in 2 weeks (peaking in first 24 hours) • 50% in 6 months7 • 3% per year after the first 6 months7,8 What is the Hunt-Hess classification? A classification that grades SAH according to symptoms at presentation and has prognostic value, correlating well with patient outcome9 What does Hunt-Hess grade 1 indicate? Asymptomatic, mild headache, slight nuchal rigidity What does Hunt-Hess grade 2 indicate? Moderate to severe headache, nuchal rigidity, no neurological deficit other than cranial nerve palsy What does Hunt-Hess grade 3 indicate? Drowsiness/confusion, mild focal neurological deficit What does Hunt-Hess grade 4 indicate? Stupor, moderate to severe hemiparesis What does Hunt-Hess grade 5 indicate? Coma, decerebrate posturing What grading system correlates with risk of vasospasm? The Fisher grading system.10 Grade I: No blood detected Grade II: Diffuse deposition of subarachnoid blood, no clots, and no layers of blood greater than 1 mm Grade III: Localized clots and/or vertical layers of blood ≥1 mm in thickness Grade IV: Diffuse or no subarachnoid blood, but intracerebral or intraventricular clots are present Which Fisher grade poses the greatest risk of clinical vasospasm? Fisher Grade III10 What is radiographic vasospasm? A narrowing of the vessels demonstrated by angiography (or noninvasive radiographic study) that may or may not be accompanied by clinical vasospasm Fig. 52.1 Cerebral angiogram, lateral view. Right carotid injection. Example of angiographic vasospasm following SAH. Note the diminished caliber of the ICA (arrows) and MCA branches (arrowheads). Why is xenon-assisted CT (Xe-CT) not typically used in the diagnosis of vasospasm? Detects global changes in blood flow, but too insensitive to detect focal changes What is the incidence of vasospasm after SAH? 30 to 70% radiographic, 20 to 30% clinical/symptomatic11 What is the feared result of progressive clinical vasospasm? A delayed ischemic neurologic deficit (DIND), characterized by confusion or decreased consciousness with or without a neurological deficit. Nonfocal neurological deficits may include headache, disorientation, or meningismus. Focal signs vary depending on the artery in spasm. What clinical signs might one expect with clinical vasospasm of the ACA? MCA? ACA vasospasm: frontal lobe signs (abulia, reemergence of grasp and suck reflexes, urinary incontinence, drowsiness, confusion), leg weakness MCA vasospasm: hemi– or monoparesis, aphasia (in dominant lobe involvement) What is the most frequent cause of vasospasm? Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage, but other intracranial hemorrhages, head trauma, brain surgery, or even lumbar puncture may induce vasospasm. How does transcranial Doppler (TCD) assist with the diagnosis of vasospasm? Narrowing of the arterial lumen increases the velocity of blood flow. TCD changes may be detectable 1 to 2 days prior to the emergence of clinical symptoms.12,13 Blood normally flows through the MCA at a rate of <120 cm/sec. Rates of 120 to 200 cm/sec and >200 cm/sec may be seen in mild and moderate vasospasm, respectively. Why is the MCA/ICA ratio (the Lindegaard ratio) often used in the diagnosis of vasospasm? It assists with differentiation of vasospasm, in which the Lindegaard ratio12 will be elevated to >3, and with other high flow states (e.g., hyperemia) where the Lindegaard ratio will be normal (<3). After SAH, when is the risk for vasospasm greatest? Post-bleed day 3 to 14, peaking on post-bleed days 6 to 8 How does the risk for post-SAH clinical vasospasm correlate with the Hunt-Hess grade? Hunt-Hess grade vasospasm risk14: Grade 1: 20% Grade 2: 36% Grade 3: 47% Grade 4: 43% Grade 5: 70% How may vasospasm be prevented? By preventing hypovolemia and anemia. Calcium channel blockers (e.g., nimodipine) theoretically may dilate arteries, provide a neuroprotectant effect, and improve outcome following SAH, but have not been shown to prevent angiographic vasospasm.15Statins may reduce the risk of vasospasm and overall mortality associated with vasospasm.16 True or false: Early surgical/endovascular treatment of ruptured aneurysms reduces the risk of post-SAH vasospasm. False. Manipulation of vessels may actually increase the risk. Early treatment, however, allows for the use of hyperdynamic therapy without the risk of rebleeding. What is cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP)? CPP is the pressure gradient driving cerebral blood flow. CPP = Mean arterial pressure (MAP) – Intracranial pressure (ICP) = Cerebral blood flow (CBF) × Cerebrovascular resistance (CVR) What is hyperdynamic or “triple H” therapy? A management option for vasospasm. Goal is to maintain cerebral perfusion pressure and prevent DIND. Hypertension (systolic blood pressure [SBP]: up to 220 mm Hg in clipped aneurysms) Hemodilution (goal hematocrit <33%) Hypervolemia (elevate CVP to 8 to 12 cm H2O or PCWP to 18 to 20 mm Hg in clinical vasospasm) What agents are often used to induce the hyperdynamic state? Hypertension: Pressors (dopamine, Levophed, Neo-Synephrine, dobutamine) Volume expansion/hemodilution: fluids (crystal-loid, colloid, blood products), desmopressin (DDAVP) When should hyperdynamic therapy be initiated? When there is a clinical suspicion of DIND or with evidence of radiographic vasospasm. Prophylactic triple-H therapy has not been shown to reduce the risk of vasospasm and is not indicated.17 What are the possible complications of hyperdynamic therapy? Intracranial: Hemorrhage in a previously ischemic area (reperfusion), increased edema and ICP Extracranial: Pulmonary edema (monitor CXR), myocardial infarction, pulmonary catheter-related complications, arrhythmias, electrolyte disorders What drugs improve the rheologic properties of blood, enhancing perfusion of ischemic zones in the setting of vasospasm? Mannitol improves microvascular perfusion by transiently lowering blood viscosity and elevating cerebral blood volume. Low doses (20%, 0.25 g/kg/h) may be useful. What are the endovascular options for vasospasm treatment? • Balloon angioplasty (leads to clinical improvement in the majority of cases but requires an interventional neuroradiologist). • Verapamil, papaverine, or nicardipine infusion (effects are less dramatic and of shorter duration than with angioplasty) What is benign perimesencephalic subarachnoid hemorrhage? A form of nonaneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (accounts for 5 to 10% of all SAH.2 Presenting symptoms are similar to aneurysmal SAH (“thunderclap headache,” meningismus, nausea/vomiting),18 but CT shows hemorrhage limited only to prepontine or perimesencephalic cisterns, and angiography fails to reveal an aneurysm. These patients typically have an uneventful clinical course and an excellent outcome.19–22 1. Taneda M, Kataoka K, Akai F, Asai T, Sakata I. Traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage as a predictable indicator of delayed ischemic symptoms. J Neurosurg 1996;84:762–768 PubMed 2. van Gijn J, Rinkel GJ. Subarachnoid haemorrhage: diagnosis, causes and management. Brain 2001;124(Pt 2):249–278 PubMed 3. Latchaw RE, Silva P, Falcone SF. The role of CT following aneurysmal rupture. Neuroimaging Clin N Am 1997;7:693–708 PubMed 4. Perry JJ, Spacek A, Forbes M, et al. Is the combination of negative computed tomography result and negative lumbar puncture result sufficient to rule out subarachnoid hemorrhage? Ann Emerg Med 2008;51:707–713 PubMed 5. Boesiger BM, Shiber JR. Subarachnoid hemorrhage diagnosis by computed tomography and lumbar puncture: are fifth generation CT scanners better at identifying subarachnoid hemorrhage? J Emerg Med 2005;29:23–27 PubMed 6. Edlow JA, Caplan LR. Avoiding pitfalls in the diagnosis of subarachnoid hemorrhage. N Engl J Med 2000;342:29–36 PubMed 7. Jane JA, Winn HR, Richardson AE. The natural history of intracranial aneurysms: rebleeding rates during the acute and long term period and implication for surgical management. Clin Neurosurg 1977;24:176–184 PubMed 8. Winn HR, Richardson AE, Jane JA. The long-term prognosis in untreated cerebral aneurysms: I. The incidence of late hemorrhage in cerebral aneurysm: a 10-year evaluation of 364 patients. Ann Neurol 1977;1:358–370 PubMed 9. Hunt WE, Hess RM. Surgical risk as related to time of intervention in the repair of intracranial aneurysms. J Neurosurg 1968;28:14–20 PubMed 10. Fisher CM, Kistler JP, Davis JM. Relation of cerebral vasospasm to subarachnoid hemorrhage visualized by computerized tomographic scanning. Neurosurgery 1980;6:1–9 PubMed 11. Kassell NF, Sasaki T, Colohan AR, Nazar G. Cerebral vasospasm following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke 1985;16:562–572 PubMed 12. Lindegaard KF, Nornes H, Bakke SJ, Sorteberg W, Nakstad P. Cerebral vasospasm after subarachnoid haemorrhage investigated by means of transcranial Doppler ultrasound. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien) 1988;42:81–84 PubMed 13. Sekhar LN, Wechsler LR, Yonas H, Luyckx K, Obrist W. Value of transcranial Doppler examination in the diagnosis of cerebral vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery 1988;22:813–821 PubMed 14. Salary M, Quigley MR, Wilberger JE Jr. Relation among aneurysm size, amount of subarachnoid blood, and clinical outcome. J Neurosurg 2007;107:13–17 PubMed 15. Allen GS, Ahn HS, Preziosi TJ, et al. Cerebral arterial spasm—a controlled trial of nimodipine in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage. N Engl J Med 1983;308:619–624 PubMed 16. Sillberg VA, Wells GA, Perry JJ. Do statins improve outcomes and reduce the incidence of vasospasm after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a meta-analysis. Stroke 2008;39:2622–2626 PubMed 17. Egge A, Waterloo K, Sjøholm H, Solberg T, Ingebrigtsen T, Romner B. Prophylactic hyperdynamic postoperative fluid therapy after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a clinical, prospective, randomized, controlled study. Neurosurgery 2001;49:593–605, discussion 605–606 PubMed 18. Singleton RH, Kostov DB, Kanaan HA, Horowitz MB. Benign perimesencephalic hemorrhage occurring after previous aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a case report. J Med Case Reports 2010;4:405 PubMed 19. Brilstra EH, Hop JW, Rinkel GJ. Quality of life after perimesencephalic haemorrhage. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1997;63:382–384 PubMed 20. Rinkel GJ, Wijdicks EF, Vermeulen M, Hageman LM, Tans JT, van Gijn J. Outcome in perimesencephalic (nonaneurysmal) subarachnoid hemorrhage: a follow-up study in 37 patients. Neurology 1990;40:1130–1132 PubMed 21. Schwartz TH, Solomon RA. Perimesencephalic nonaneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: review of the literature. Neurosurgery 1996;39:433–440, discussion 440 PubMed 22. van Gijn J. Subarachnoid haemorrhage. Lancet 1992;339:653–655 PubMed

Subarachnoid Hemorrhage and Vasospasm

References

Subarachnoid Hemorrhage and Vasospasm

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree