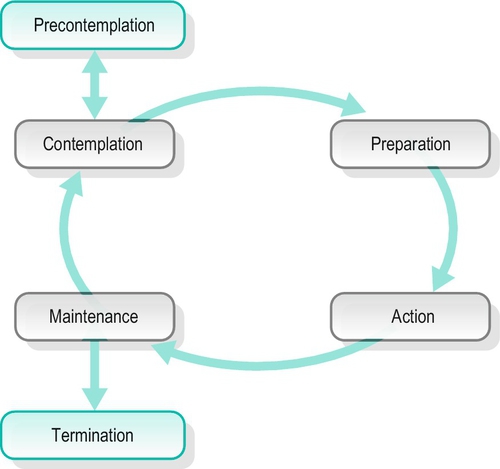

28 Jenny Lancaster; John Chacksfield CHAPTER CONTENTS Definitions of Substance Misuse Historical and Cultural Context National Policies and Guidance Substance Use: An Occupational Perspective Substance Misuse Treatment in Context Structured Comprehensive Assessments and Interviews Occupational Therapy Assessment Performance Skills and Client Factors Context, Environment and Activity Demands Engagement and Principles of Intervention Mutual Aid – Self-Help Approaches OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY AND SUBSTANCE MISUSE Occupational therapists in all fields of practice are likely to meet service users who have problems with substance misuse. This chapter is a starting point for occupational therapists interested in the specialism of substance misuse, as well as those who work in other areas of mental health and encounter substance misuse alongside mental health problems. It focuses on the nature and extent of substance misuse in the UK, offering an occupational perspective on why people take drugs and the types of problems the individual drug user may experience. The occupational therapy process is also outlined and the role of the therapist highlighted. Treatment approaches are described as well as specific occupational therapy intervention strategies. Substance use and misuse are widespread within our society and culture. Some 90% of the adult UK population drink alcohol and about 10% of the population drink above recommended daily guidelines (Strategy Unit 2003). It is estimated that 30–50% of people with severe mental health problems misuse substances (Cabinet Office 2004). The prevalence of illegal drug misuse is harder to assess but it is estimated that 1% of the UK population uses heroin or cocaine (NTA 2002). The term ‘substance use’ generally means the consumption of alcohol or psychoactive drugs that have the potential to be addictive. Substance misuse has been defined as drug and/or alcohol taking that harms the individual, their significant other(s) or the wider community (NTA 2002). Substance dependence or dependence syndrome (first proposed by Edwards and Gross 1976) is a specific diagnostic term describing what is commonly termed addiction (Ashworth et al. 2008; Gerada and Ashworth 2008; DH 2011). Although there are myriad substances that are used and abused due to their psychoactive properties, this chapter will focus on the most harmful ones: heroin and alcohol. The use of addictive substances has been entwined with human occupation throughout humankind’s history. Archaeological evidence exists for the use of alcohol in ancient Egypt from as early as 6000 BC (Nunn 1996). In Britain in the 17th century, due to the lack of drinking-water, beer and gin were commonly drunk by the whole population throughout the day, starting at breakfast (Allen 2001; Tyler 1995). One-third of England’s farmland was devoted to growing barley for beer and one in seven buildings was a tavern. In the second half of the century, 2000 coffee houses sprang up in London. This had a sobering effect on the population. Instead of getting drunk in taverns, coffee houses provided a safe place to read, play games and engage in political debate. Indeed, the first ballot box was used in the Turk’s Head Coffee House in London. This change from the use of a depressant substance (alcohol) to a stimulant (caffeine in coffee) has been associated with increased literacy, political change and improved standards of living (Allen 2001). However, during the Industrial Revolution alcohol use dramatically increased in response to changes in the occupational lives of workers – toiling in factories and mines – and increasing urbanization (Tyler 1995). From 1950 to 2004, consumption of alcohol per capita increased from 3.9 litres of pure alcohol per year to 9.4 litres per year. Although this has reduced slightly since 2004, annual consumption levels have remained above 7 litres since 1980 (BMA 2008). The UK has one of the highest rates of binge drinking in the Europe, particularly among young people (Institute of Alcohol Studies 2010). Binge drinking has been defined as drinking more than double the recommended daily limit of units of alcohol. In the UK, 40% of all drinking episodes for men and 22% for women are defined as binge drinking (Institute of Alcohol Studies 2010). There are vast differences in consumption of alcohol between different religious, ethnic and socioeconomic groups in the UK. For example, 9% of the white British population do not drink alcohol, whereas 90% of those of Pakistani or Bangladeshi origin abstain from alcohol (BMA 2008). Culture mediates views of substances in terms of how dangerous they are and how legal they should be. For example, the Christian moralist Temperance movement in 19th-century Britain set out to reduce alcohol consumption (Berridge 2005). At the end of the 19th century, cocaine was highly popular and recommended by doctors such as Sigmund Freud. Many cultures use and have used drugs in social, ritual or religious ceremony and for pleasure. In the UK, substance use from the 18th to the early 20th century, was primarily seen as a sin. The drunk and the ‘opium sot’ were seen as morally depraved. The turn of the 20th century saw this attitude change towards a much more disease-oriented concept, including the notion of treatment and cure. In the 1960s came the concept of dependence – acknowledging psychological reliance on a drug – and in the 1970s, this was developed into the modern dependence syndrome. Over recent years, drug treatment strategies have repeatedly focused on and measured success in terms of reducing the costs to society caused by substance use rather than the personal recovery of people using substances. For example, the frequently quoted Drug Treatment Outcomes Research Study (Donmall et al. 2009) showed that every £1 spent on drug treatment saves society £2.50. Interestingly, analysis of the final report of this study found that ‘gains in the patients’ health-related quality of life would normally be considered too small in themselves to justify the cost of treatment’ (Drug and Alcohol Findings 2010, p. 5). Dual diagnosis or comorbidity refers to the coexistence of a substance misuse disorder and a separate mental health problem (Kavanagh et al. 2000; Teeson et al. 2000). Research shows that substance users have higher rates of mental health problems than the general population (DoH 2002). Mental health problems may be induced by drug use or drugs are used to self-medicate the symptoms. Recent recommendations by nurse consultants suggest that dual diagnosis is the norm rather than the exception and all mental health professionals should receive training in both issues as a matter of course. When alcohol and drugs are used by people with mental health problems, they can severely exacerbate symptoms and disrupt treatment. They are associated with disrupted lifestyles, suicide (Duke et al. 1994) and violent behaviour (Swanson et al. 1990). The issue of substance misuse by people with a mental health problem has been important within UK government policy, since the Policy Implementation Guide on Dual Diagnosis (DoH 2002). Valuable guidance documents created by experts and published via the charities Rethink and Turning Point (Rethink and Turning Point 2004; Turning Point 2007) highlight key aspects of treatment for dual diagnosis and recommend various intervention strategies that address the complex combination of issues. There is general agreement that good practice should be comprehensive (integrated into one service where possible), long term, adopt a staged approach to recovery and be focused on developing self-management skills and functional goals (Drake et al. 2001). Currently in the UK, substances that are misused are categorized as legal or illegal and are subject to restrictions according to age. Substance misuse can lead to social, psychological, physical or legal problems related to intoxication or regular excessive consumption and/or dependence (NTA 2002). The health and social consequences of drug and alcohol use are comprehensively summarized in A summary of the health harms of drugs (DH 2011), some of which are described later in the chapter. Frequently, people develop substance misuse problems in an attempt to deal with problems in their lives; such as following the breakdown of a relationship, due to unemployment or as an attempt to relieve the symptoms of mental health problems. It is therefore important to consider the interrelation of three factors in relation to substance misuse (Gossop 2000; Ghodse 2002): the drug, the individual and their environment. Examining the relationship between the individual and the environment in relation to their occupations is a core component of occupational therapy. When working with service users misusing substances, occupational therapists consider how the substance use (or abstinence from a previously habitually used substance) affects a person’s occupations. For example, an individual’s alcohol consumption may increase due to changes in their work environment, or an ex-heroin user who, having given up a large network of drug-using friends, may feel they do not have the confidence to engage in new leisure activities alone. Substance misuse has been described as a chronically relapsing condition (NTA 2002). Research indicates extremely high relapse rates (60%) following an episode of substance misuse treatment (NIDA 2009) and that relapse is most likely within a short period following initial treatment (Hunt et al. 1971; Stephens and Cottrell 1972; Milkman et al. 1984). However, the largest multisite trial in the UK has proved the long-term effectiveness of drug treatment (Donmall et al. 2009). The costs of drug and alcohol misuse for communities are high. It is estimated that the cost of alcohol misuse in England is £18–25 billion a year and the cost of illegal drug misuse in England is around £15.4 billion per year (HM Government 2010). Therefore drug and alcohol misuse has been high on the political agenda for many years, with numerous policies and the development of links between the criminal justice system and treatment services. For example, the Drug Intervention Programme developed Arrest Referral Schemes (Skodbo et al. 2007). Since the advent of HIV and the development of structured methadone maintenance programmes, treatment for opiate use has traditionally adopted a harm reduction or harm minimization approach. This is designed to reduce the risk of infection with blood-borne viruses through sharing injecting equipment, as well as avoiding the risks associated with using contaminated, adulterated street heroin. These approaches include providing needle exchange schemes, providing education for drug users on safer injecting methods, and prescribing medical substitute opiates such as methadone. This has undoubtedly been successful in preventing an epidemic of HIV among injecting drug users and substitute prescribing has enabled many drug users to live productive lives whilst continuing to be prescribed an opiate drug. However, these approaches have caused much debate over what constitutes successful treatment and recovery. There is a longstanding disagreement and debate in the field of drug treatment between supporters of ‘harm reduction’ approaches and those that follow ‘12 Step’ approaches (Alcoholics Anonymous 2002), with are based on total abstinence. When a BBC report in October 2007 (BBC 2007) reported that only 3% of drug users left treatment free of all drugs (including methadone) despite a huge increase in funding for Drug Treatment, it sparked a debate among many prominent figures in the treatment field (see Drugscope 2009). A range of guidelines for treatment have been developed by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) – such as CG115 Alcohol dependence and harmful alcohol use (NICE 2011). These are available at www.nice.org.uk. The UK government’s Drug Strategy (HM Government 2010) marks a change in direction with an increased focus on detoxification and abstinence from substitute prescribing as a goal of treatment. This is not without controversy due to large-scale studies that highlight the increased risk of drug-related deaths after stopping substitute prescribing (Cornish et al. 2010). Once ‘tolerance’ to opiates is lost through the detoxification process, there is a high risk of death through accidental overdose if the drug user relapses and uses similar amounts as before. Alcohol and drugs act on specific centres of the brain. For example, opiates (such as heroin) act on the opiate receptor in areas of the brain such as the limbic system, specifically the nucleus accumbens and the ventral tegmentum (Carter 1998). Changing the state of these receptors by using drugs creates the pleasurable experiences. Many drugs are thought to act on the dopamine system. Dopamine is a chemical messenger which plays an important role in the brain’s reward centre. It is released when we do pleasurable things, such as eating good food or having sex. Drugs such as cocaine and heroin cause a massive surge of dopamine to be released, creating the sensation of pleasure. Over time, repeated drug use can lead to dopamine receptor sites in the brain being reduced or shut down. Therefore, the drug user finds less effect from using a drug, which leads to an increase in the amount used. The other significant effect is that the drug user may experience a decreased ability to feel pleasure or satisfaction in activities of daily life (Whitten 2009). This can lead to further drug use or thrill-seeking activities. Occupational therapists need to be aware of this because service users who have recently stopped using drugs and have reduced dopamine levels, may struggle to feel satisfaction from the occupations selected as therapeutic media. Alcohol has a variety of complex actions but is generally a nervous system depressant. The reason alcohol appears to produce euphoria is that it depresses frontal cortex functioning, resulting in loss of inhibition. Alcohol is legal for use by people over the age of 18. The legality of other drugs is determined in the UK by the Misuse of Drugs Act (HMSO 1979). This classifies drugs as Class A, B or C. Each class carries particular penalties for using and supplying the drug. Therapists working with drug users need to be aware of Section 8 of the Misuse of Drugs Act, which makes it an offence to allow drug dealing in any public premises. This Section was used to convict two managers of a charity drop-in centre for the homeless in Cambridge in 2000 (BBC News website 2000). Despite a strict anti-drug use policy they were convicted for refusing to pass on confidential information about their service users to the police and were judged to have not done enough to prevent drug dealing in their centre. Press coverage of the case has been collated on the Innocent website (see Innocent 2000). People are known to use substances for many and varied reasons (Edwards 1987; Gossop 2000). Alcohol, for example, is widely used as a social lubricant, to reduce tension, to intoxicate as a way of coping with negative feelings or as a sedative. Heroin use is described as offering a warm, dreamy ‘cocoon’ and, for many users, it serves as an antidote to emotional pain and the stress of a life lacking in meaning (Tyler 1995). Substance use is often closely tied to human occupational behaviour. Some of the reasons for substance use can be categorized under the headings below but it is important to note that each individual drug user will have their own specific reasons for taking drugs. ■ Avoiding occupation: through intoxication, stimulus seeking, denial of responsibility or through escape into drug culture ■ As a coping mechanism: to counter anxiety, relieve pain, mask distress, increase confidence and peer acceptance or as self-medication for mental health problems ■ To alter perception: to develop a wider understanding of life, for desired spiritual attainment, as part of a religious ritual, to assist creativity, to enjoy drug-induced perception ■ To develop meaning in life: through the ritual and habits of drug-taking behaviour, the routine of obtaining drugs or drug-dealing, the excitement of illegal activities, or through interacting and sharing a culture with associates in a drug-using network ■ To enhance occupations: by celebrating positive events, enhancing good feelings, or removing negative emotional states ■ To manage occupational risk factors: to cope with occupational deprivation and/or boredom (‘killing time’) or coping with occupational imbalance such as the pressure of too many demands on one’s time. Many people regulate their use of alcohol and other drugs without causing damage to themselves or others. However, the use of alcohol and other drugs commonly leads to a range of physical, psychological and social problems. Substance use can be problematic, disrupting a person’s normal lifestyle balance or physical state or leading to dependence syndrome (Edwards et al. 1981). Drug or alcohol dependence includes physical withdrawal symptoms as well as compulsive urges to use a substance. See Drummond (1992) for further explanation of the relationship between problems and dependence. Before considering drug and alcohol treatment, it may be useful to present a transtheoretical model of change that can be used with individuals with any addictive behaviour (or anyone working towards behaviour change). The Stages of Change model is a useful tool for guiding treatment goal-setting and interventions (see Fig. 28-1), which can be targeted to help service users progress through the stages of change. FIGURE 28-1 A model of change. (Reprinted and adapted from Prochaska J O, DiClemente C C 1986 Towards a comprehensive model of change. In: Miller R J, Heather N (eds) Treating addictive behaviours: processes of change. Plenum, London, with permission from Springer Science + Business Media). Prochaska and DiClemente (1982, 1986) and Prochaska et al. (1992) first developed this model with cigarette smokers, who they found reported progression through different stages of change as they attempted to give up. These same stages have since been observed in all other addictive disorders (Gossop 1994). It reflects the reality that it is normal for an individual to go through all the stages several times before achieving lasting behaviour change. Most of us can relate to attempting behaviour changes – such as dieting, exercising regularly or stopping smoking perhaps – where we have not succeeded in maintaining the change at the first attempt. In fact, the smokers in Prochaska and DiClemente’s initial study went round the cycle between three and seven times before finally giving up smoking permanently. The relapses associated with addiction (a chronic relapsing condition) may be seen as normal events that can be learned from, rather than being seen as indications of failure. Although represented as a cycle, it is now conceptualized as a spiral acknowledging that each time the person goes through the stages, they are learning from the experience of previous attempts to change. The central concept of this model is that behaviour change takes place through the following discrete stages: ■ Contemplation. In this stage, the person recognizes that their behaviour is problematic and considers doing something about it. This change is characterized by ambivalence. Motivational enhancement therapy or motivational interviewing is a useful, evidence-based approach to use during this stage ■ Preparation The person prepares to change ■ Action. This stage is about making changes, implementing a plan ■ Maintenance. This is about sustaining the change, integrating the change into the individual’s lifestyle. In this model, a person may slip back a stage or exit the cycle into precontemplation at any time. Establishing at which stage the individual is, enables the therapist to select the most appropriate intervention. For example, a service user in the maintenance phase may benefit from learning stress management techniques and developing satisfying day-to-day occupations, which are important in boosting confidence and preventing relapse. However, these strategies are likely to be wasted on a ‘precontemplator’. Buijsse et al. (1999) give further guidance to occupational therapists using this framework. The Stages of Change model is an effective means to assess readiness for treatment. This is a significant predictor of engagement and retention (Project MATCH Research Group 1993; Simpson et al. 1997). For alcohol users, a standardized assessment – the Readiness for Change questionnaire (Heather et al. 1991) – can be completed. In addition to assisting in treatment matching, this model is helpful in setting realistic and achievable goals; that is, aiming to move to the next stage in the cycle, rather than trying to stop the behaviour immediately. It is an optimistic approach in that relapse is viewed as a normal part of the process of achieving long-term behaviour change. Occupational therapy is ideally suited to the maintenance phase but the therapist needs to be able to assess at what stage the service user is, and respond accordingly. Drug and alcohol treatment services are operated by the NHS, Social Services, prisons, private clinics and the voluntary sector. Treatment settings include hospital and community locations, and treatment can commence in either of these. Entry into treatment is usually triggered by a crisis. For example, an individual is arrested committing burglary to fund a growing crack cocaine habit, or loses their job after their work performance suffers due to heavy drinking. A crisis often shifts an individual from precontemplation into contemplation. This can provide a window of opportunity to encourage engagement in treatment. Consequently, treatment services often target crises for this reason. For example, specialist alcohol nurses may assess people attending Accident and Emergency services or drug users may be assessed while in police custody, as described below. People with alcohol and drug problems are frequently referred for treatment by their GP, self-refer or are referred after an alcohol-related physical problem is identified, such as in A&E. Others are referred from within the criminal justice systems. Some referrals come from employers or employee assistance programmes. Since 2000, there have been increased links between the criminal justice system and treatment services. Alcohol Treatment Orders and Drug Rehabilitation Requirements (formerly Drug Treatment and Testing Orders) were introduced as part of the Criminal Justice Act 2003 (HMSO 2003). These are treatment orders or suspended sentences for those convicted of a drug- or alcohol-related crime and involve the person agreeing to a programme of drug testing and participation in structured treatment, often as an alternative to a custodial sentence. Arrest referral schemes also operate whereby those held in police custody are offered a brief assessment by a drug or alcohol worker who aims to facilitate entry into treatment for those identified as having problematic drug or alcohol use. Drug and alcohol misuse within the forensic mental health system has been the subject of several papers (McKeown et al. 1996). Occupational therapy programmes in these settings have been described by Chacksfield and Forshaw (1997) and Chacksfield (2003). Assessment needs to be tailored, needs-led and part of an ongoing process (NTA 2002). Many guidelines stress the importance of expressing empathy and a non-judgemental manner (DH et al. 2007; NICE 2011), recognizing both the stigma that service users feel as well as ambivalence about change that is common at the beginning of treatment. A number of assessment techniques may be used, including: ■ structured questionnaires ■ interviews ■ risk assessment ■ observation (for signs of physical withdrawal) ■ physiological assessments (e.g. urine and blood analysis, ECG). A number of screening assessments are available. For alcohol, NICE recommends the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), Severity of Alcohol Dependence Questionnaire (SADQ) and Alcohol Problems Questionnaire (APQ) tools (NICE 2011). NHS staff should be competent to identify harmful drinking and alcohol dependence and competent to initially assess the need for an intervention (NICE 2011). For drug use, there is the Severity of Dependence Scale (Gossop et al. 1995), which is designed to be generic for a range of drugs. It is essential to monitor withdrawal (Edwards 1987) and assessments are often used to assist this, such as the Short Opiate Withdrawal Scale (Gossop 1990). The standard outcome measure in drug treatment services is the Treatment Outcomes Profile (TOP) (Marsden et al. 2007), as required by the National Drug Treatment Monitoring System (NDTMS). This outcome measure is also validated for those with alcohol problems. Structured questionnaires aim to investigate the severity of dependence, the range and complexity of problems associated with substance use (including the effects of drug-using behaviour on dependent children) and motivation to engage in treatment or to change substance use behaviour. These can follow a standard mental health interview approach but should also cover the number of different drugs used, the amount used, a typical day of use and a history of use, including the first drug use occasion and changes in use over time. There may also be assessment of anxiety or depression. NICE recommends that for those with alcohol problems a ‘motivational intervention’ is carried out using key elements of motivational interviewing – such as helping people to recognize the problems caused by their drinking, resolving ambivalence, encouraging belief in the ability to change and being persuasive and supportive rather than confrontational (NICE 2011). Occupational therapy investigates six domains: activity demands, context and environment, performance patterns, performance skills, areas of occupation and client factors (AOTA 2008). These have been grouped into three areas as follows. All categories of human daily activity, such as activities of daily living, leisure, self-maintenance and work/productivity, can be affected by substance use. As described earlier, occupational therapists are concerned that substance misuse and dependence disrupts the balance of work, self-care and leisure (Rotert 1989; Chacksfield 1994; Morgan 1994; Martin et al. 2008). Quantitative research by occupational therapists, such as Mann and Talty (1990), Scaffa (1991), Stoffel et al. (1992) and Chacksfield and Lindsay (1999) has highlighted use of leisure time by alcohol-dependent service users as a key problem area. Successful engagement in performance areas requires ability in terms of sensorimotor, cognitive, psychosocial and psychological components. Drug action can have both short- and long-term effects on performance components. Occupational therapy research has suggested that low motivation and low self-esteem are significant in substance misusers (Viik et al. 1990; Stoffel et al. 1992). Research by Martin et al. (2008) with homeless substance misusers admitted to a residential recovery programme, explored performance capacity issues, as well as their impact on quality of life, using a variety of ratings, including the Occupational Performance History Interview II (OPHI-II) (Kielhofner 2008). Positive changes in occupational competence (based on OPHI-II scores) were associated with recovery at the 6-month stage of follow-up after a dip in scores at 3 months, which the authors attributed to the impact of the environment. The research appears to suggest that occupational competence is a key factor in recovery from addiction. Research into cue exposure (Drummond et al. 1995) shows that environmental cues can trigger addictive behaviour in individuals. Someone returning to an alcohol- or drug-orientated environment on discharge is likely to re-experience the same cues as before and may relapse back into substance use without developing coping strategies to counteract the environmental effects. Occupational therapists may wish to supplement the standard initial interview with open questioning to obtain information about how substance use is impacting on the individual’s occupational performance areas, components and contexts. The Occupational Circumstances Assessment Interview and Rating Scale (OCAIRS) (Forsyth et al. 2005) is a semi-structured interview often used for this purpose. Other appropriate tools include: ■ Occupational Self-Assessment (OSA) ■ Rosenberg Self-Esteem Inventory ■ Self-Efficacy Scale ■ Volitional Questionnaire ■ Coping Responses Inventory (CRI) ■ Interest Checklist ■ Role Checklist ■ Assessment of Motor and Process Skills (AMPS) ■ Internal/External Locus of Control Scale ■ Occupational Performance History Interview (II). As described earlier, substance dependence is typically a chronically relapsing condition. Interventions often do not follow a linear path and the Stages of Change Model is useful in assessing treatment readiness and in selecting the most appropriate intervention. Many people with substance misuse problems struggle to engage with treatment services. Feelings of ambivalence, anxieties about change, fluctuating levels of motivation and a chaotic lifestyle are factors in this. Enhancing engagement is pivotal in achieving positive treatment outcomes (NTA 2004; DH 2007; NICE 2011) and the importance of establishing rapport and empathy, and of using motivational enhancement techniques following assessment, must not be underestimated (NTA 2004). People with drug and/or alcohol problems frequently present with complex needs. They may be clinically depressed, have poor physical health and be homeless. Therefore, it is important that treatment plans are comprehensive, involving other disciplines and agencies as needed (Edwards 1987; DoH 1996). People can also feel that they are overwhelmed and controlled by their addiction. Therefore, it is important to emphasize empowerment and hope in overcoming substance problems or dependence. Medically assisted withdrawal (commonly known as detoxification or detox) followed by abstinence is recommended for people who are physically dependent on alcohol. This usually occurs in the community but may need to be on an inpatient basis if there is a risk of withdrawal seizures. NICE (2010) recommends that brief interventions (Bien et al. 1993) are offered in a range of settings including primary care and A&E designed to help people reduce alcohol use to less harmful levels. Those with less severe alcohol problems and binge drinkers may opt for controlled drinking. This means keeping alcohol consumption within safe levels by adhering to a set of personal rules, such as not drinking alone, not having more than two drinks a day, and not drinking on consecutive days. After becoming abstinent or successfully controlling alcohol, NICE (2011) recommends that people are offered: ■ Cognitive behavioural therapy (discussed more fully in Ch. 15). This is often provided in the form of a relapse prevention approach, which will be discussed later ■ Behavioural therapies such as cue exposure, whereby a person is repeatedly exposed to learnt cues to drink alcohol until they habituate to those cues and the cravings to drink are extinguished ■ Social network and environment-based therapies, whereby an individual is supported to build a network of family and friends that are supportive of a change in drinking. Recreational, social and vocational activities can be encouraged on the basis that developing a non-substance-using network and developing a role or a positive identity may be key factors in preventing relapse (McIntosh and McKeganey 2000) ■ Behavioural couples therapy. This is a manual-based method combining cognitive behavioural therapy with methods that address relationship problems caused by the alcohol use. Frequently, the first stage of treatment for opiate users is stabilization using substitute prescribing (such as methadone or buprenorphine). This aims to stop the user experiencing unpleasant withdrawal symptoms but does not provide a ‘high’. The rationale behind substitute prescribing is that the drug user no longer has to inject street heroin, with its associated health risks, or be involved in illegal activities in order to fund a habit. Long-term prescription of methadone, or methadone maintenance, aims to allow users to stabilize their drug use and therefore their lives and, combined with psychological and social support, make positive lifestyle changes. It requires close monitoring due to the risk of overdose or harm related to illicit drug or alcohol use. In practice this stabilization can take a long time to achieve due, for example, to a longstanding chaotic lifestyle, the social environment of drug-using friends, and the continued desire to use drugs to escape from reality. Many service users also have physical, social, legal and psychological problems which need to be addressed as part of a comprehensive treatment plan. Once an individual has achieved stability in their lives, they may consider a ‘detox’ from substitute opiate medication. This is normally followed by a period of rehabilitation or rehab, usually in a residential or day programme. NICE (2007) recommended that contingency management be introduced to drug treatment services. This is a behavioural approach based on operant conditioning, whereby incentives are offered, often in the form of vouchers that can be exchanged for goods or services. Giving the voucher is contingent on drug tests being negative regarding illicit drug use. In the contingency management approach, the value of vouchers increases with increasing periods of continuous abstinence. There is potential for these vouchers to be used to support occupational and recovery-focused goals such as paying for gardening equipment, art materials or sessions in a sports centre. However, since the publication of this guidance, contingency management appears not to have been introduced anywhere in the UK. Despite a clear evidence base demonstrating the cost-effectiveness of this approach (Lussier et al. 2006), this may be due to the resource implications of funding the vouchers, drug testing and administration of these schemes, as well as the political repercussions. For example, health minsters may fear a public backlash, particularly in a time of austerity, against ‘paying’ drug users to engage in treatment when people with other conditions are not, and may in fact be facing cuts to care services. Nonetheless, Kings College and the Institute for Psychiatry are conducting research into the implementation of contingency management in the UK (King’s College 2012). There are numerous models of substance misuse treatment and it is beyond the scope of this chapter to cover all of them. However, those of most relevance to occupational therapists will now be described. These approaches are recommended in national guidelines (NICE 2007, 2011). The most well known by far are the ‘12 Step’ approaches of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and its associate Narcotics Anonymous (NA). The 12 Step approach is a self-help movement that offers an extensive support network of group meetings for substance users and their families. In this approach, an individual achieves recovery by progressing through the 12 steps with the support of a sponsor (mentor). Criticism has been levelled at the requirement that those who attend AA or NA must adhere to the idea that dependence is a disease and must constantly remind themselves that they are alcoholic, even when they have been abstinent for many years. Additionally, criticism is directed at the idea that a higher power is responsible for an AA or NA member’s abstinence, suggesting that this removes the responsibility for sobriety from the individual. Recent research has found that it is the supportive social network provided by the 12 Step approaches – rather than the associated belief system – that generates good outcomes. This research recommends that treatment providers de-emphasize the philosophy of the 12 Step approaches but encourage attendance as a means of gaining social support that promotes abstinence. Studies show that changing one’s role from being someone in need of help to someone who provides help to others and takes an active role in meetings (such as simply making coffee, initially) was associated with positive outcomes, more so than just attending (Pagano et al. 2004; Weiss et al. 2005). A growing, secular alternative to 12 Step approaches is SMART recovery (Smart Recovery UK 2010). A programme is offered online with a network of meetings and volunteers based on motivational enhancement therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy and rational emotive behaviour therapy. Relapse prevention (RP) is a widely used intervention based on cognitive behavioural therapy. Marlatt and Gordon (2005) describe RP as a self-management programme designed to enhance the maintenance phase of the Stages of Change model. NICE (2007) recommend that this approach is only routinely offered to those with co-existing anxiety and depression. However, as described earlier in relation to dual diagnosis, it is likely that most service users will present with these additional problems. RP focuses on ‘self-management and the techniques and strategies aimed at enhancing maintenance of habit change’. It is ‘a self-control programme that combines behavioural skills training, cognitive interventions and lifestyle change procedures’ (Wanigaratne et al. 1990, p. 1). There is a growing body of evidence supporting the effectiveness of RP interventions (Carroll 1996; Irvin et al. 1999). The RP approach uses cognitive behavioural strategies to help people learn how to anticipate and cope with situations and problems that might lead to a relapse (Wanigaratne et al. 1990). It focuses on the notions of high-risk situations and coping strategies available to the individual. Research shows that people who are aware of potential relapse situations and who use specific strategies can effectively reduce their risk of relapse (Litman 1980; Kirby et al. 1995). Boredom and negative mood states are most likely to precipitate a relapse. Second comes social pressure and being offered, or talking about, drugs. Other risk factors include interpersonal conflict and environmental cues. Initial stages of relapse prevention focus on enabling the individual to develop a good awareness of internal and external triggers to craving, such as through diary-keeping. Service users are encouraged to identify their own possible relapse triggers and to work on these with the therapist. The therapist, either in a group setting or individually, helps the individual to analyse these situations. The person will also be taught how to analyse situations on their own. Structured problem-solving techniques are used as well as role-play or rehearsal of relapse situations. There are specific cognitive behavioural techniques (Marlatt and Gordon 2005; Wanigaratne et al. 1990) used to assist people in preventing relapse – such as problems of immediate gratification (PIGs). These techniques see craving as being caused by high-risk situations and external cues. Marlatt (2010) proposes a method for managing urges, called ‘urge surfing’. This is based on mindfulness and the facilitation of detachment, whereby the thought ‘I notice I am feeling the urge to drink’ replaces the act of immediately drinking, on the understanding that the urge will arise and then subside. Coping with the urge by not responding to it at its peak starves it. Coping strategies such as relaxation methods, distraction, biofeedback or other approaches, may assist this technique. RP also stresses the importance of global lifestyle change, which aims to enable people to: ■ arrive at a balanced lifestyle ■ learn effective time management (to fill up the vacuum left by giving up the substance) ■ discover and take-up positive activities ■ identify and change unhealthy habit patterns. It can be seen from these approaches that relapse prevention fits well with occupational therapy, particularly because it focuses on individuals’ lifestyles and the day-to-day situations that cause relapse. In such work, occupational performance areas, components and contexts are critical to treatment success. Developing psychological performance components, such as self-esteem and volition, can help an individual cope with environmental triggers to relapse. The term ‘recovery’ in the field of addiction generally has a different meaning to the way it is used in general mental health practice, and it remains a controversial term according to different treatment approaches. According to the 12 Step approaches, there is an emphasis on defining oneself as being ‘in recovery’ or as ‘a recovering addict’ once one has become completely abstinent from all drugs and alcohol. Recently the UK Drug Policy Commission (UKDPC 2008) created a description of recovery drawing on different approaches to addiction and the model of recovery in mental health: The process of recovery from problematic substance use is characterized by voluntary control over substance use which maximizes wellbeing and participation in the rights, roles and responsibilities of society (UKDPC 2008).

Substance Misuse

INTRODUCTION

Definitions of Substance Misuse

Historical and Cultural Context

DUAL DIAGNOSIS

SUBSTANCE MISUSE

National Policies and Guidance

What are Drugs?

Drug Action

Legality

Why Do People Use Substances?

Substance Use: An Occupational Perspective

When Does Drug Use Go Wrong?

TREATMENT OF SUBSTANCE MISUSE

A Model of Change

Stages of Change

Substance Misuse Treatment in Context

Triggers to Treatment Entry

Referral

Referral via the Criminal Justice System

Multidisciplinary Assessments

Screening Assessments

Structured Comprehensive Assessments and Interviews

Occupational Therapy Assessment

Performance Patterns

Performance Skills and Client Factors

Context, Environment and Activity Demands

Occupational Therapy Assessment Tools

INTERVENTIONS

Engagement and Principles of Intervention

Treatment Options

Alcohol Misuse

Drug Misuse

Contingency Management

Approaches to Intervention

Mutual Aid – Self-Help Approaches

Relapse Prevention

A note on the language of recovery

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree