Suicide and deliberate self-harm

The assessment of suicidal risk

The management of suicidal patients

The management of deliberate self-harm

Introduction

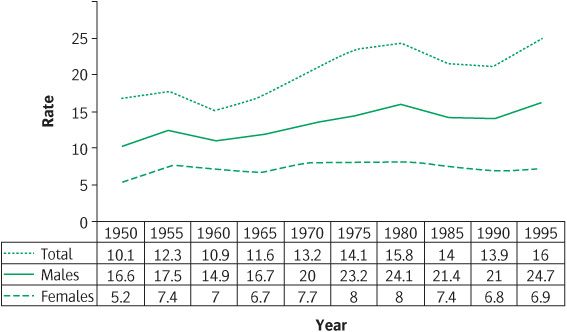

Suicide is among the ten leading causes of death in most countries for which information is available, and there are some indications that the rate is increasing (see Figure 16.1). In the UK it is the third most important contributor to life years lost after coronary heart disease and cancer. Over the last three decades, several countries have reported a considerable increase in the number of young men who kill themselves, although in recent years there have been some signs that this trend may be reversing. The subject is important to all doctors who may at times encounter people who are at risk for suicide, and who may also at times be involved in helping family members or others after a suicide. The importance of the subject is reflected in national and international initiatives for suicide prevention (Department of Health, 2002; Mann et al., 2005).

Figure 16.1 Global suicide rates (per 100000), by gender, for the period 1950–95 (selected countries indicated in Table 16.1). Reproduced from Figures and Facts about Suicide, World Health Organisation, p. iv, © World Health Organization, 1999 http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1999/WHO_MNH_MBD_99.1.pdf accessed 26/03/12 with permission.

For every suicide it is estimated that more than 30 non-fatal episodes of self-harm occur. Depression, substance misuse, and other mental health problems are more common in people who deliberately harm themselves, and the rate of suicide in the year following an episode of deliberate self-harm (DSH) is some 60–100 times that of the general population (Hawton et al., 2003a). The rate of suicide is also raised in the period following discharge from inpatient psychiatric care. For these reasons, psychiatrists need to be particularly well informed about the nature of DSH and suicidal behaviour, and about strategies aimed at their prevention. For an overview of relevant aspects of suicide and DSH, see Wasserman and Wasserman (2009).

Suicide

The act of suicide

Suicide has been defined as an act with a fatal outcome, deliberately initiated and performed in the knowledge or expectation of its fatal outcome. People who take their lives do so in a number of different ways. In England and Wales, according to the Office for National Statistics in 2008, hanging was the most commonly used method for suicide by men (53%), followed by drug overdose (16%), self-poisoning by car exhaust fumes, drowning, and jumping. The commonest methods for women were drug overdose (36%), hanging (34%), and drowning (Wasserman and Wasserman, 2009). In the USA, gunshot and other violent methods are more frequent than in the UK.

Most completed suicides have been planned. Precautions against discovery are often taken—for example, choosing a lonely place or a time when no one is expected. However, in most cases a warning is given. In a US study, suicidal ideas have been expressed by more than two-thirds of those who die by suicide, and clear suicidal intent by more than one-third. Often the warning had been given to more than one person. In an early British study of people who had committed suicide (Barraclough et al., 1974), two-thirds had consulted their general practitioner for some reason in the previous month, and 40% had done so in the previous week. Around 25% were seeing a psychiatrist, of whom 50% had seen the psychiatrist in the preceding week. Data from the National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide (2009) suggest that 25–29% of suicides have been in recent contact with mental health services.

The epidemiology of suicide

The accuracy of the statistics

Accurate statistics about suicide are difficult to obtain because information about the exact cause of a sudden death is not always available. For example, in England and Wales, official figures depend on the verdicts reached in coroners’ courts. A verdict of suicide is recorded by a coroner only if there is clear evidence that the injury was self-inflicted and that the deceased intended to kill himself. If there is any doubt about either point, a verdict of accidental death or an open verdict is recorded. Open verdicts are more often recorded when the method of self-harm is less active (e.g. drowning compared with hanging) and when the deceased is younger (Neeleman and Wessely, 1997). It is accepted that official statistics underestimate the true rates of suicide. Barraclough (1973) demonstrated that among those whose deaths were recorded as accidental, many had recently been depressed or dependent on drugs or alcohol, resembling those who commit suicide. In Dublin in the 1970s, psychiatrists ascertained four times as many suicides as did coroners, and similar discrepancies have been reported elsewhere. An attempt has been made to overcome these problems by reporting ‘probable suicides’, which combine deaths attributed to suicide and ‘open verdicts’ (Schapira et al., 2001).

Differences in suicide rates

For these reasons, caution should be exercised when comparing rates of suicide in different time periods and between different countries. Despite this, long-standing and fairly stable differences in rates of suicide between different countries are apparent. The finding of Sains-bury and Barraclough (1968) that, within the USA, the rank order of suicide rates among immigrants from 11 different nations reflected those within the 11 countries of origin supports these differences in national rates. The current suicide rate in the UK (10.1 per 100 000 in men and 2.8 per 100 000 in women) is in the lower range of those reported in Western countries. Generally, higher rates are reported in eastern and northern European countries, and lower rates in Mediterranean countries. The suicide rates in the former Soviet Union have increased substantially since its break-up, particularly among men (53.9 per 100 000 for the Russian Federation and for Lithuania, and 63.3 per 100 000 for Belarus (World Health Organization, 2010). Reported suicide rates are very low in Islamic countries. The gender differences are less in Asian than in Western countries. Some methods of suicide reflect local culture (e.g. self-immolation or ritual disembowelment) (Cheng and Lee, 2000). In Hong Kong, poisoning from carbon monoxide produced by burning charcoal has recently become a frequent method of suicide (Leung et al., 2002).

Changes in suicide rates

Suicide rates have changed in several ways since the beginning of the last century. Recorded rates for both men and women fell during each of the two world wars. There were also two periods during which rates increased. The first, during 1932 and 1933, was a time of economic depression and high unemployment. However, the second period, between the late 1950s and the early 1960s, was not. Following this, from 1963 to 1974 the rates declined in England and Wales but not in other European countries (with the exception of Greece), or in North America. The decline in England and Wales seems to have resulted mainly from a change in the domestic gas supply from a toxic form derived from coal to a non-toxic form obtained from wells in the North Sea. Before this change, suicide using domestic gas had been the most frequent method of suicide.

Variations with the seasons

In England and Wales, suicide rates have been highest in spring and summer for every decade since 1921–30. A similar pattern has been found in other countries in both hemispheres. The reason for these fluctuations is not known, although it has been suggested that they relate to changes in the incidence of mood disorders. There is now evidence that seasonal variations in suicide rates may be diminishing (Ajdacic-Gross et al., 2008).

Demographic characteristics

Suicide is about three times as common in men as in women. The highest rates of suicide in both men and women are in the elderly. Suicide rates are lower among the married than among those who have never been married, and increase progressively through widowers, widows, and the divorced. Rates are higher in the unemployed. With regard to socio-economic groups, the highest rates are seen in unskilled workers, followed by professionals. Rates of suicide are high among prisoners, especially among those on remand.

Rates are particularly high in certain professions. The rate in veterinary surgeons is four times the expected rate (Bartram and Baldwin, 2010), and in pharmacists and farmers it is double the expected rate (Charlton et al., 1993). Suicide rates are also higher in doctors, particularly female doctors (Meltzer et al., 2008). Suicide among doctors is discussed further on p. 426.

The causes of suicide

Methods of investigation

Investigations into the causes of suicide face several difficulties. Information about the health and well-being of the deceased at the time of suicide cannot be obtained directly. Prospective studies of suicide are difficult to arrange because of its relative rarity. Two strategies have been used to overcome these difficulties.

1. Retrospective studies have pieced together the circumstances that surrounded the suicide by examining records and interviewing doctors, relatives, and friends who knew the deceased well.

2. Epidemiological studies have examined associations between social and demographic factors and rates of suicide in different populations at different times.

Both approaches have methodological problems. However, the first, which has become known as the ‘psychological autopsy’, has helped to identify factors that precede suicide. The second approach has informed our understanding of social circumstances that may give rise to increased rates of suicide.

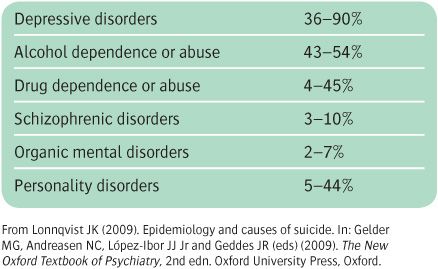

Individual psychiatric and medical factors

The most consistent finding of studies of individual factors (see Table 16.1) is that the large majority of those who die from suicide have some form of mental disorder at the time of death (Barraclough et al., 1974). Similar results have been reported in other countries (Cheng and Lee, 2000), although in some rural regions the association of diagnosed psychiatric disorder with suicide appears to be less strong (Manoranjitham et al., 2010; Tong and Phillips, 2010). The most frequent conditions include the following:

• Personality disorder. This is diagnosed in up to almost 50% of people who commit suicide, according to some surveys (Foster et al., 1997).

• Mood disorder. About 6% of individuals who have a mood disorder will die by suicide. Depressed patients who die by suicide are more likely than other depressed patients to have a past history of self-harm and to have experienced a sense of hopelessness (Fawcett et al., 1990). They are also more often single, separated, or widowed, are older, and are more often male. A review of community studies showed that the majority of patients who died by suicide had (according to psychological autopsy) a depressive illness and had recent suboptimal or no treatment for their illness (Wasserman and Wasserman, 2009). Those receiving no treatment in the same review were 1.8 times more likely to commit suicide.

• Alcohol misuse. Follow-up studies of patients dependent on alcohol show a continuing risk of suicide, with a lifetime risk of 7% (Inskip et al., 1998; Wilcox, 2004). Among those who are alcohol dependent, suicide is more likely when the patient is male, older, has a long history of drinking, and has a history of depression and of previous suicidal attempts. Suicide risk is also increased among those whose drinking has caused physical complications, relationship problems, difficulties at work, or arrests for drunkenness offences.

• Drug misuse. This is relatively common among those who die by suicide, particularly in the young (Wilcox, 2004).

• Schizophrenia. The suicide rate is increased among young men early in the course of the disorder, particularly when there have been relapses, when there are depressive symptoms, and when the illness has turned previous academic success into failure. The lifetime risk of suicide in this group has been estimated to be 5% (Hor and Taylor, 2010).

Other factors associated with suicide are a past history of DSH (see p. 433) and poor physical health, especially epilepsy. For a review, see Stenager and Stenager (2000).

Social factors

Comparisons of the rates of suicide between and within different countries have been conducted over a period of many years. None has been more influential than that undertaken by Emile Durkheim at the end of the nineteenth century (Durkheim, 1951). Durkheim examined variations in the rate of suicide within France, and between France and other European countries. He demonstrated that a range of social factors have an impact on rates of suicide. Rates were lower at times of war and revolution, and increased during periods of both marked economic prosperity and economic depression. He concluded that social integration and social regulation were central to the rate of suicide. Durkheim described four types of suicide, including ‘anomic’ suicide. This refers to suicide by a person who lacks ties with other people and no longer feels part of society. (Durkheim’s other types of suicide were egoistic, altruistic, and fatalistic.)

Table 16.1 Rates of mental disorders in five psychological autopsy studies on completed suicides using DSM-III or DSM-III-R criteria

More recent studies have repeatedly demonstrated that areas with high unemployment, poverty (Gunnell et al., 1995), divorce, and social fragmentation (Whitley et al., 1999) have higher rates of suicide. Such studies cannot be used as a means of examining the characteristics of individuals who kill themselves, but they do provide important information about factors within society that may affect the rate of suicide. Cross-cultural evidence indicates wide variation in the meaning of suicide and social attitudes to it, which appears to be associated with differences in suicide rates (Stack, 2000).

Another social factor that appears to affect rates of suicide is media coverage of suicide. Suicide and attempted suicide rates were shown to increase after television programmes and films depicting suicide (Hawton et al., 1999b). High-profile suicides sometimes affect the means and timing of a suicide (Gould et al., 1990). The precise nature of the media content may also be influential in increasing or decreasing the risk of imitative behaviour (Niederkrotenthaler et al., 2010).

Biological factors

A family history of suicide is associated with suicide, and adoption studies (Wender et al., 1986) indicate that this mechanism is genetic. The genetic mechanism may be largely independent of those giving rise to any psychiatric disorder (Roy et al., 2000), and perhaps related to personality traits of impulsivity and aggression.

Suicidal behaviour has been linked to decreased activity of brain 5-HT pathways. Markers of 5-HT function, such as cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) 5-HIAA and the density of 5-HT transporter sites, are lowered in suicide victims. The association between underactivity of 5-HT pathways and suicidal behaviour appears to extend across diagnostic boundaries, and may be related to increased impulsivity and aggression in those with low brain 5-HT function. The link between 5-HT function and suicidality has prompted genetic association studies in people with suicidal behaviour. However, reliable associations with 5-HT-related and other genes have not yet emerged (Carballo et al., 2008). For reviews of the neurobiology and genetics of suicide, see Ernst et al. (2009) and Uher and Perroud (2010).

Psychological factors

Psychological factors in suicide have been derived mainly by extrapolation from studies of non-fatal DSH, but the factors may not be the same. An exception is the work by Beck and colleagues, who followed more than 200 patients who had been hospitalized because of suicidal ideation (Beck et al., 1985). They demonstrated that people who had high scores on a measure of hopelessness had very high rates of suicide over the following 5 to 10 years. Subsequent research has indicated other psychological variables that may be associated with suicidal behaviour, including impulsivity, dichotomous thinking, cognitive constriction, problem-solving deficits, and overgeneralized autobiographical memory. All of these could act by predisposing an individual to act impulsively (Williams and Pollock, 2000).

Conclusion

The associations considered above do not, of course, establish causation, but they do suggest three sets of interacting influences:

1. medical factors, including depressive disorder, alcohol misuse, and abnormal personality

2. psychological factors, of which hopelessness is the strongest

3. social factors, especially social isolation and poverty.

Personality traits of impulsivity and aggression could be important, and these may have a biological basis, possibly related to dysregulation of the 5HT system.

Special groups

Suicide among those in contact with psychiatric services

Given the strong association between mental disorder and suicide, it is not surprising that many people who kill themselves are in contact with psychiatric services. The National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide, which was set up in 1997, collects information on all patients who committed suicide while in contact with the mental health services (National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide, 2009). Between 1997 and 2007, coroners recorded a verdict of suicide or an open verdict in 54 808 deaths, of which 14 249 (26%) had been in contact with mental health services during the preceding 12 months. During this period the annual number of inpatients dying by suicide had decreased by 46% and the number dying by strangulation or hanging had decreased by 69%. Of the patients who died by suicide under psychiatric care, 62% were male and 23% were within 1 week of admission. Hanging remained the commonest method (42%), followed by jumping either from a height or in front of a vehicle (31%) (Hunt et al., 2007). Suicide after discharge from hospital occurred within 1 month in 43% of 238 patients studied, and nearly 50% of these suicides occurred before the first follow-up appointment (Hunt et al., 2009). The first week after discharge is the period of highest risk.

These findings indicate that the following measures are necessary.

• Support patients intensively during the first few weeks after discharge from hospital, with the first follow-up generally taking place within a few days of discharge or of going on leave.

• Plan in advance the steps that should be taken if the patient ceases to cooperate with treatment.

• Monitor the side-effects of drugs, and change to one with fewer side-effects if these seem likely to lead to refusal to continue with the medication.

• Ward design. Since hanging is a common method of suicide by inpatients, ensure that wards do not contain avoidable structures (‘ligature points’) from which this could be effected.

‘Rational’ suicide

Despite the findings reviewed above, suicide can be the rational act of a mentally healthy person. Several European countries (e.g. Switzerland, the Netherlands, Belgium) have recognized this and made changes in their law to allow those with a long-term illnesses to take their own life with help from friends, family, or even medical practitioners. An established and well-documented decision is generally required, together with confirmation that the individual does have capacity. The law has not yet changed in the UK, but interpretation of recent cases indicates that it is moving in that direction and may change. The major concern is to draft a bill with wording to protect elderly people from pressure from family who are either burdened by their care or likely to benefit financially by their death. Public opinion has certainly shifted towards a recognition that reasonable people may, in some circumstances, want to end their own lives. Lack of personal autonomy and perceived dignity due to infirmity and chronic pain are the commonest reasons advanced by those who pursue this path.

It is a good general rule to assume, until further enquiry has proved otherwise, that a person who talks of suicide has an abnormal state of mind. If the assumption is correct—and it is sometimes difficult to identify a depressive disorder when the person is first seen—the patient’s urge to die is likely to diminish when their abnormal mental state recovers. Moreover, even when the decision to die was arrived at rationally, it is still reasonable to attempt to prevent the person from self-harm. This is because a decision about suicide may have been made rationally but on the basis of incomplete information or mistaken assumptions. It may change when the person is better informed—for example, when it has been explained to them that death from cancer need not be as painful as they formerly believed.

Older people

In most countries the highest rate of suicide is among people aged over 75 years. The most frequent methods are hanging among men, and drug overdose among women (Harwood et al., 2000a). In addition to active self-harm, some older adults die from deliberate self-neglect (e.g. by refusing food or necessary treatment). As in younger age groups, depression is a strong predictor of suicide in the elderly. Other risk factors are social isolation and impaired physical health, although the latter may act in part through causing depression (Conwell et al., 2002). Personality is also important, especially anxious and obsessional traits (Harwood et al., 2000b). For further information about suicide in the elderly, see Harwood and Jacoby (2000).

Children and adolescents

Children

Suicide is rare in children. In 1989, the suicide rate for children aged 5–14 years was estimated to be 0.7 per 100 000 in the USA and 0.8 per 100 000 in the UK. Little is known about the factors that lead to suicide in childhood, except that it is associated with severe personal and social problems. Children who have died by suicide have usually shown antisocial behaviour. Suicidal behaviour and depressive disorders are common among their parents and siblings (Shaffer, 1974). Shaffer distinguished two groups of children. The first group consisted of children of superior intelligence who seemed to be isolated from less educated parents. Many of their mothers were mentally ill. Before death, the children had appeared depressed and withdrawn, and some had stayed away from school. The second group consisted of children who were impetuous, prone to violence, and resentful of criticism (Shaffer et al., 2000).

Adolescents

Suicide rates among adolescents have increased in recent years. In England and Wales the increase has mainly been in male adolescents aged 15–19 years (McClure, 2000), and the principal methods among males have been hanging, and poisoning with car exhaust fumes (Hawton et al., 1999a). A psychological autopsy study (Houston et al., 2001) showed that about 70% of adolescents who killed themselves had had psychiatric disorders, mainly depressive and personality disorders, which were sometimes comorbid. Many of them had misused alcohol or drugs. The suicide was often the culmination of long-term difficulties with relationships and other psychosocial problems. Approximately two-thirds of these individuals had made a previous suicide attempt.

Ethnic groups

Rates among immigrants closely reflect those in their countries of origin. In the UK, there is particular concern about possible high rates of suicide among Asian women (Ahmed et al., 2007).

High-risk occupational groups

Doctors. The suicide rate among doctors is higher than that in the general population, and the excess is greater among female doctors than among males (Meltzer et al., 2008). Many reasons have been suggested for the excess, including the ready availability of drugs, increased rates of addiction to alcohol and drugs, the extra stresses of work, reluctance to seek treatment for depressive disorders, and the selection into the medical profession of predisposed personalities. A psychological autopsy study of 38 working doctors who had died by suicide (Hawton et al., 2004a) found psychiatric disorder—mainly depressive disorder and/or drug or alcohol misuse—in about two-thirds of cases, and problems at work in a similar proportion. About one-third of cases had relationship problems, and about a quarter had financial problems. Self-poisoning with drugs was more common than in the general population, and 50% of the anaesthetists used anaesthetic agents. Rates have been reported to be higher in anaesthetists, community health doctors, general practitioners, and psychiatrists (Hawton et al., 2000). It is not known whether this relates more to factors in the individual (contributing to specialty choice and to suicide rate) or to the nature of the work.

Veterinary surgeons have the highest suicide rates of any professional group. The reasons for this are unclear, but are likely to closely parallel those identified for doctors, and include managerial issues, a high workload, and possibly the impact of regularly euthanizing sick animals (Platt et al., 2010).

Farmers also have high rates of suicide. Possible causes include the ready availability of means of self-harm (e.g. poisons and firearms), together with work stress and financial difficulties (Malmberg et al., 1999).

Students, contrary to popular belief, are not a high-risk group, with rates close to their age group in the general population.

Suicide pacts

In suicide pacts, two (or occasionally more) people agree that at the same time each will take his or her own life. Completed suicide pacts are uncommon. In Far Eastern countries, those involved are usually lovers aged under 30 years, and in Western countries they are usually interdependent couples aged over 50 years. Suicide pacts have to be distinguished from cases where murder is followed by suicide (especially when the first person dies but the second is revived), or where one person aids another person’s suicide without intending to die him- or herself.

The psychological causes of these pacts are not known with certainty. Usually the two people have a particularly close relationship but are socially isolated from others. Often a dominant partner initiates the suicide (Brown and Barraclough, 1999).

Mass suicide is occasionally reported. For example, 913 followers of the People’s Temple cult died at Jonestown, Guyana, in 1978, and 39 members of the Heaven’s Gate Cult in California died in 1997. These tragic events are generally initiated by a charismatic leader who has strong convictions and is sometimes deluded. Sometimes there is evidence to suggest murder followed by suicide within the group.

There have been several cases in which the Internet has been used to arrange suicide pacts (Rajagopal, 2004).

The assessment of suicidal risk

General issues

Every doctor should be able to assess the risk of suicide. There are two requirements. The first is a willingness to make direct but tactful enquiries about the patient’s intentions. There is no convincing evidence that asking a patient about suicidal inclinations makes suicidal behaviour more likely. On the contrary, someone who has already thought of suicide is likely to feel better understood when the doctor raises the issue, and this feeling may reduce the risk.

The second requirement is to be alert to factors that predict suicide. However, prediction based on these factors has a low sensitivity and specificity. Even if the risk is correctly assessed as high, it is difficult to predict when the suicide will take place. The limitations of prediction have been illustrated by a study by Goldstein et al. (1991). They tried to develop a statistical model to predict the suicides from among a group of high-risk hospital patients, but failed to identify a single one of the 46 patients who later committed suicide. The same conclusion was drawn by Kapur and House (1998).

Assessment of risk

The most obvious warning sign is a direct statement of intent. It cannot be repeated too often that there is no truth in the idea that people who talk of suicide do not do it. On the contrary, two-thirds of those who die by suicide have told someone of their intentions. However, a difficulty arises with people who talk repeatedly of suicide. In time their statements may no longer be taken seriously, being discounted as manipulation. However, some who repeatedly make such threats do eventually kill themselves. Just before the act, there may be a subtle change in their way of talking about dying, sometimes in the form of oblique hints instead of former more open statements.

Risk is assessed further by considering factors that have been shown to be associated with suicide (see p. 423). Factors that point to greater risk include the following:

• marked hopelessness

• a history of previous suicide attempts: around 40–60% of those who die by suicide have made a previous attempt

• social isolation

• older age

• depressive disorder, especially with severe mood change with insomnia, anorexia, and weight loss

• alcohol dependence, especially with physical complications or severe social damage

• drug dependence

• schizophrenia, especially among young men with recurrent severe illness, depression, intellectual deterioration, or a history of a previous suicide attempt (see p. 294 and p. 425)

• chronic painful illness

• epilepsy

• abnormal personality.

Completing the history

When these general risk factors have been assessed, the rest of the history should be evaluated. The interview should be conducted in an unhurried and sympathetic way that allows the patient to admit any despair or self-destructive intentions. It is usually appropriate to start by asking about current problems and the patient’s reaction to them. Enquiries should cover losses, both personal (e.g. bereavement or divorce) and financial, as well as loss of status. Information about conflict with other people and social isolation should also be elicited. Physical illness should always be enquired after, particularly any painful condition in the elderly. (Some depressed suicides have unwarranted fears of physical illness as a feature of their psychiatric disorder.)

When assessing previous personality, it should be borne in mind that the patient’s self-description may be coloured by depression. Whenever possible, another informant should be interviewed. The important points include mood swings, impulsive or aggressive tendencies, and attitudes towards religion and death.

Mental state examination

The assessment of mood should be particularly thorough, and cognitive function must not be overlooked. The interviewer should then assess suicidal intent. It is usually appropriate to begin by asking whether the patient thinks that life is too much for them, or whether they no longer want to go on. This first question can lead to more direct enquiries about thoughts of suicide, specific plans, and preparations for suicide, such as saving tablets. It is important to remember that severely depressed patients occasionally have homicidal ideas—they may believe that it would be an act of mercy to kill other people, often their partner or a child, to spare them intolerable suffering. Such homicidal ideas should always be taken extremely seriously.

Assessment of risk among inpatients

The suicide of a hospital inpatient is always of particular concern, and it is important to be able to identify those at risk. Unfortunately, the general guiding risk factors noted above are present in so many of those admitted that they differentiate poorly between degrees of risk. The problem is illustrated by the results of a retrospective case–control study of inpatients who had committed suicide (Powell et al., 2000). The authors identified five predictors—suicidal ideation, recent bereavement, delusions, chronic mental illness, and family history of suicide. An inpatient with all five risk factors would have a risk of about 30%, but only about 1 in 100 patients had all five factors. For the rest, the sensitivity and specificity of the predictors was low, with most of those who died having predicted risks of 1% or less. This approach generates too many false-positives to be a practical proposition.

The management of suicidal patients

General issues

Having assessed the suicidal risk, the clinician should make a treatment plan and try to persuade the patient to accept it. The first step is to decide whether the patient should be admitted to hospital or treated as an outpatient or day patient. This decision depends on the intensity of the suicidal intention, the severity of any associated psychiatric illness, and the availability of social support outside hospital. If outpatient treatment is chosen, the patient should be given a telephone number so that they canobtain help at any time if they feel worse. Frustrated attempts to find help can be the last straw for a patient with suicidal inclinations.

If the immediate risk of suicide is judged to be high, inpatient care is likely to be required unless there is an effective crisis management team in the community, or the patient lives with reliable relatives who wish to care for the patient themselves, understand their responsibilities, and are able to fulfil them. Such a decision requires an exceptionally thorough knowledge of the patient and their problems, and of the relatives. If hospital treatment is essential and the patient refuses it, admission under a compulsory order will be necessary. In most countries imminent suicide risk is sufficient for detention for observation, but the duration and conditions will vary. Readers should be aware of and follow the legal requirements of the place in which they work.

Management in the community

The management of patients who have been identified as being at risk of suicide but do not require admission involves continuing assessment of the suicidal risk, and agreed plans for appropriate treatment and support (see Table 16.2). Where they are available and the patient consents to this, relatives or other carers should be involved. The key worker should liaise closely with other members of the community team to ensure that there will be a prompt and appropriate response if the patient or the carers ask for additional help. If medication is required—for example, to treat a depressive disorder—the drug that is least dangerous in overdose should be chosen. The choice should be discussed with the general practitioner, and small quantities should be prescribed on each occasion. When appropriate, medication should be kept safely by the carer. Both patients and carers need to know how to obtain immediate help in an emergency.

Management in hospital

The obvious first requirement is to prevent patients from harming themselves. These arrangements require adequate staffing and a safe ward environment. A policy (see Table 16.3) should be agreed with all staff members when the patient is admitted.

Ward arrangements. Wards design should minimize the availability of means of self-harm. This includes preventing access to open windows and other places where jumping could lead to serious injury or death, removing ligature points from which hanging could take place (e.g. by boxing in pipework), preventing access to ward areas in which self-injury would be easier to enact, and removing potentially dangerous personal possessions such as razors and belts. If the risk is high, special nursing arrangements may be needed to ensure that the patient is never alone.

Table 16.2 Care of the potentially suicidal patient in the community

The management policy (see Table 16.3) should be:

• reviewed carefully at frequent intervals until the danger passes

• explained to and agreed with each new shift of staff, especially when the review has led to changes in the plan

• explained to and if possible agreed with the patient. If the patient does not agree to necessary parts of the plan, the reasons for these should be carefully explained. If the patient still refuses to collaborate, and the risk is high, compulsory treatment may be required.

Table 16.3 Care of the suicidal patient in hospital

If intensive supervision is needed for more than a few days, the patient may become irritated by it and try to evade it. Staff should anticipate this, ensure that treatment of any associated mental illness is not delayed, and support the patient intensively while waiting for the treatment to have an effect. However determined the patient is to die, there is usually some small remaining wish to go on living. If the staff adopt a caring and hopeful attitude, those remaining positive feelings can be encouraged, generating a more positive view of the future. The patient can then be helped to see how an apparently overwhelming accumulation of problems can be dealt with one by one.

The risk of suicide is higher during periods of home leave arranged to test readiness for discharge. It is also greater during the period immediately before discharge, and in the first few weeks after discharge (see p. 425). Therefore the discharge plan should include early reassessment, effective psychological and social support, and rapid response to any need for extra help. Plans for leave and for discharge should be discussed with the patient and their concerns elicited. If appropriate, the plans should be modified.

However carefully patients are cared for, suicide will happen, despite all the efforts of the staff. The doctor then has an important role in supporting others, particularly nurses who have come to know the patient particularly well. Although it is essential to review every suicide carefully to determine whether useful lessons can be learned, this process should never become a search for a scapegoat.

The relatives

When a patient has died by suicide, the relatives require not only the support that is appropriate for any bereaved person, but also help with the common responses of anger, guilt, and a feeling that they could have done more to prevent the death. Barraclough and Shepherd (1976) found that relatives usually reported that the police conducted their enquiries in a considerate way, but that the public inquest was very distressing. Subsequent newspaper publicity caused further grief, reactivating the events surrounding the death and increasing any feelings of stigma. Sympathetic listening, explanation, and counselling are likely to help relatives with these difficulties. Anger is often a part of this grief, and should be met by a willingness to listen and to provide full information. Wertheimer (2001) has reviewed the consequences of suicide for relatives.

Suicide prevention

In population terms, suicide is a rare event. In Western Europe it accounts for approximately one to two deaths per 10 000 people per year. Therefore a controlled trial of an intervention to reduce suicide would require many thousands of participants. Such trials have not been conducted. However, there is some evidence from observational studies to suggest measures that could affect the rate of suicide in the population (see Table 16.4). Such possible measures will be discussed next. For further information, see Hawton (2000b).

Service changes

Educating primary care physicians. The effectiveness of interventions based in primary care is equivocal. In a frequently quoted study, Rutz and colleagues involved all of the general practitioners on the Swedish island of Gotland in 1983 and 1984 in order to evaluate the impact of teaching about the diagnosis and treatment of affective disorder. The suicide rate fell significantly below both the long-term suicide trend on Gotland and that for Sweden as a whole. By 1988, three years after the project had ended, the suicide rate had returned almost to baseline values (Rutz et al., 1992). The researchers concluded that the programme had been effective, but that it would need to be repeated every 2 years to have long-term benefits, and that it appeared to benefit only females. These findings were replicated by Henriksson and Isacsson (2006).

Improving psychiatric services. Earlier recognition and better treatment of the psychiatric disorders might be expected to reduce suicide rates. However, it has proved difficult to demonstrate this empirically.

Table 16.4 Suicide prevention

Targeting high-risk groups. The usual clinical approach is to provide additional help for high-risk groups such as patients who have recently received inpatient psychiatric treatment, and those who have recently deliberately harmed themselves. (Crisis services are discussed below.)

Long-term medication. Although the continued prescribing of antidepressants during the period following an episode of depression reduces the risk of a subsequent episode of depression, a reduction in suicidal behaviour has not been demonstrated. However, there is accumulating evidence that lithium prophylaxis reduces suicide rates (Cipriani et al., 2005b), and some evidence that clozapine may reduce suicide attempts among people with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.

Prescribing less toxic antidepressants. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are less toxic in overdose than tricyclic antidepressants. On the other hand, SSRIs have been reported to cause the emergence or worsening of suicidal ideas in young people, possibly because they can cause agitation and insomnia initially. Although it is not possible to reach a decisive conclusion on the basis of the available evidence, it seems that the overall risk of suicide associated with SSRIs is similar to that with tricyclic anti-depressants (Cipriani et al., 2005a). Furthermore, one US study demonstrated an increased rate of suicide attempts in the month before antidepressant medication was prescribed (Simon et al., 2006). In addition, there is some evidence from epidemiological studies that increased prescribing of less toxic antidepressants such as SSRIs is associated with a decrease in population suicide rates, although this has been contested (Isacsson et al., 2010). Until the evidence is conclusive, the most appropriate drug should be decided for each individual patient, and their progress monitored and support provided during the first few weeks of treatment.

Counselling services. In the UK, the best known service for people who are suicidal is the Samaritan organization, which was founded in London in 1953 by the Reverend Chad Varah. People who are in despair are encouraged to contact a widely publicized telephone number. The help that is offered (‘befriending’) is provided by non-professional volunteers, who have been trained to listen sympathetically without attempting to take on tasks that are in the province of a professional. An often quoted survey found that, among people who telephone the Samaritans, the suicide rate in the ensuing year is higher than in the general population (Barraclough and Shea, 1970). This finding suggests that the organization attracts people at risk for suicide, but does not indicate how far the help that is offered may be beneficial. Comparisons of matched towns with and without services suggest that there is little difference in suicide rates (Jennings et al., 1978). Even if this is so, the Samaritans provide valuable support for many lonely and despairing people.

Population strategies

Reducing the availability of methods of suicide

The ease with which people can access lethal methods of self-harm may affect the rate of suicide using those methods, and may have some effect on suicide rates in general. If the available methods are less harmful, more people will be resuscitated. No matter what changes are made, however, people who are determined to kill themselves can eventually find the means to do so. The following changes have been made.

Detoxification of gas. In Britain, between 1948 and 1950, poisoning by domestic coal gas accounted for 40% of reported suicides among men and 60% of those among women. Following the introduction of less toxic North Sea gas, the number of suicides using this method decreased dramatically, and the national rate of suicide also fell. Kreitman (1976) argued that the removal of coal gas was responsible for this change.

Detoxification of car exhaust fumes. The fitting of catalytic converters to motor vehicles to reduce the toxicity of car exhaust fumes may have reduced the number of deaths using this method.

Restricting amounts of analgesics. In the UK, government legislation has limited the amount of paracetamol, salicylates and their compounds that an individual can buy at one time. There is evidence that this legislation has reduced suicides from overdoses of these drugs (Hawton et al., 2004b).

Removing and preventing access to hazards. In hospital wards and police and prison cells, ligature points from which hanging could take place should be removed or enclosed (see p. 429). Physical barriers on bridges, train platforms, and other potentially dangerous places may reduce the number of suicides at these places.

Other measures

More responsible media reporting. Sometimes people copy methods of suicide that have received widespread media coverage. For this and other reasons, reporters and editors have been encouraged to report suicide responsibly. In 2006, following a submission from the Samaritans, the Press Complaints Commission added a new sub-clause to the section ‘Intrusion into Grief and Shock’, which now states that ‘when reporting a suicide, care should be taken to avoid excessive detail about the method used’ (Press Complaints Commission, 2007).

Social policy. Given the repeatedly demonstrated association between unemployment and suicide, it has been argued that policies aimed at reducing rates of unemployment may help to reduce the rate of suicide (Lewis et al., 1997). Factors such as increasing social isolation may also need to be tackled in this way. Although the means of achieving such strategies are far from clear, and it would be difficult to evaluate their effectiveness, such calls are a reminder of the relationship between social policy and health.

Public education. Campaigns to educate the public about mental illness and its treatment have included outreach to schools, which has involved teaching about solving problems and seeking help when distressed. The value of such approaches is uncertain.

Deliberate self-harm

Until the 1950s, little distinction was made between people who killed themselves and those who survived after an apparent suicidal act. In the UK, Stengel (1952) was the first to identify epidemiological differences between the two groups. He proposed the term ‘attempted suicide’ to describe self-injury that the person could not be sure to survive. Subsequent studies of the motivation for such episodes found that the intention of many of the survivors had not been to die. As a result, the terms deliberate self-poisoning, parasuicide and deliberate self-harm were introduced to describe episodes of intentional self-harm that did not lead to death and may or may not have been motivated by a desire to die. Kreitman (1977) defined this behaviour as ‘a non-fatal act in which an individual deliberately causes self-injury or ingests a substance in excess of any prescribed or generally recognized dosage.’ The Royal College of Psychiatrists encourages the use of the term self-harm, and non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) has also been proposed. In this chapter, the term deliberate self-harm (DSH) will be used to describe such incidents.

Acts that end in suicide and acts of DSH overlap one another. Some people who had no intention of dying succumb to the unintended effects of an overdose. Others who intended to die are revived. Importantly, many people were ambivalent at the time of the act, uncertain whether they wished to die or to survive. It should be remembered that, among people who have been involved in DSH, the suicide rate in the subsequent 12 months is about 100 times greater than in the general population, and remains high for many years. Therefore DSH should not be regarded lightly.

The act of deliberate self-harm

Methods of deliberate self-poisoning

In the UK, about 90% of the cases of DSH that are referred to general hospitals involve a drug overdose, and most of them present no serious threat to life. The type of drug used varies somewhat with age, local prescription practices, and the availability of drugs. The most commonly used drugs are the non-opiate analgesics, such as paracetamol and aspirin. Paracetamol is particularly dangerous because it damages the liver and may lead to the delayed death of patients who had not intended to die. It is particularly worrying that younger patients, who are usually unaware of these serious risks, often take this drug. Anti-depressants (both tricyclics and SSRIs) are taken in about 25% of episodes. About 50% of people consume alcohol in the 6 hours before the act (Hawton et al., 2007).

Methods of deliberate self-injury

Deliberate self-injury accounts for about 10% of all DSH presenting to general hospitals in the UK. The commonest method of self-injury is laceration, usually cutting of the forearms or wrists; it accounts for about 80% of the self-injuries that are referred to a general hospital. (Self-laceration is discussed further below.) Other forms of self-injury include jumping from a height or in front of a train or motor vehicle, shooting, and drowning. These violent acts occur mainly among older people who intended to die (Harwood and Jacoby, 2000).

Deliberate self-laceration

There are three forms of deliberate self-laceration:

1. deep and dangerous wounds inflicted with serious suicidal intent, more often by men

2. self-mutilation by schizophrenic patients (sometimes in response to hallucinatory voices) or people with severe learning difficulties

3. superficial wounds that do not endanger life, more often inflicted by women.

Only the last group will be described here.

Usually, the act of laceration is preceded by increasing tension and irritability, which diminish afterwards. After the act, the patient often feels shame and disgust. Some of these individuals report that they lacerated themselves while in a state of detachment from their surroundings, and that they experienced little or no pain. The lacerations are usually multiple, made with glass or a razor blade, and inflicted on the forearms or wrists. Some of these people also injure themselves in other ways (e.g. by burning with cigarettes, or inflicting bruises).

Self-cutters who attend hospital are more often men (Hawton et al., 2004c). People who cut themselves superficially do not always seek help from the medical services, and many of these people are young females, often with personality problems characterized by low self-esteem, and sometimes impulsive or aggressive behaviour, unstable moods, difficulty in interpersonal relationships, and problems with alcohol and drug misuse.

The epidemiology of deliberate self-harm

DSH is the main risk factor for completed suicide. Although there is no national DSH register, there are several local registers that track its incidence. In the early 1960s, a substantial increase in DSH began in most Western countries. In the UK, the rates varied during the 1970s and 1980s and increased again through the 1990s. A national suicide prevention strategy in 2002 aimed to reduce suicide by 20% by 2010. DSH has been falling during this decade, particularly in males, and this parallels falling suicide rates (Bergen et al., 2010). Current estimates of the rate of DSH in the UK suggest a figure of about 4 per 1000 per year. The rates in most European countries are lower (see Kerkhof, 2000).

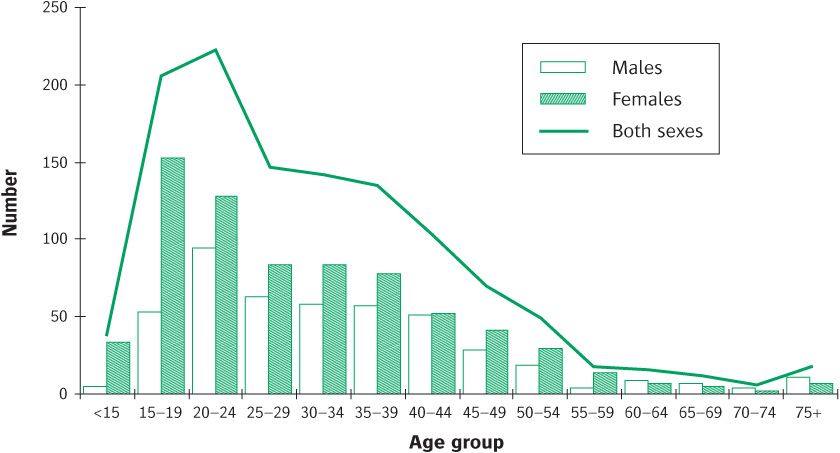

Variations according to personal characteristics

DSH is more common among younger people, with the rates declining sharply in middle age (see Figure 16.2). Over recent years, the proportion of men presenting following DSH has risen. In the 1960s and 1970s the female-to-male ratio was about 2:1, whereas recent studies show much smaller differences. The peak age for men is older than that for women. For both sexes, rates are very low under the age of 12 years. DSH is more prevalent in those of lower socioeconomic status and who live in more deprived areas. There are also differences in relation to marital status. The highest rates for both men and women are among the divorced, and high rates are also found among teenage wives, and younger single men and women (Hawton et al., 2003b).

Rates of DSH in the elderly have changed little in recent years. Their characteristics seem to be more similar to those of individuals who kill themselves than of younger people who harm themselves deliberately (Harwood and Jacoby, 2000).

Figure 16.2 Age groups of deliberate self-harm patients by gender in 2002. Reproduced by permission of Professor KE Hawton, Oxford University, Oxford.

Causes of deliberate self-harm

Precipitating factors

Compared with the general population, people who harm themselves deliberately have experienced four times as many stressful life problems in the 6 months before the act (Paykel et al., 1975). The events are various, but a recent quarrel with a partner, girlfriend, or boyfriend is common. Other events include separation from, or rejection by, a sexual partner, the illness of a family member, recent personal physical illness, and appearance in court.

Predisposing factors

Familial and developmental factors may predispose to DSH (Statham et al., 1998). There is some evidence that early parental loss through bereavement, or a history of parental neglect or abuse, is more frequent in people who harm themselves.

Personality disorder. In the UK (Haw et al., 2001) and other countries (e.g. Suominen et al., 1996), personality disorder is identified in almost 50% of DSH patients. Borderline personality disorder has been reported to be common, but other studies have found anxious, anankastic (obsessional), and paranoid personality disorders more frequently (Haw et al., 2001). Impulsiveness, and poor skills in solving interpersonal problems, may also predispose to DSH.

Long-term problems with partner. An important early study by Bancroft et al. (1977) found that about two-thirds of the DSH patients had a problem in their relationship with a partner.

Economic and social environment. Rates of DSH are higher among the unemployed. However, unemployment is related to other social factors associated with DSH, such as financial difficulties, and it is difficult to determine whether unemployment is a direct cause. Rates of DSH are also higher in areas of socio-economic deprivation (Hawton et al., 2001).

Ill health. A background of poor physical health is common.

Psychiatric disorder

It used to be held that, with the exception of adjustment disorder, psychiatric disorder was uncommon among people who harmed themselves deliberately. However, if standardized assessments are used, psychiatric disorder has been detected in about 90% of DSH patients who are seen in hospital (Suominen et al., 1996; Haw et al., 2001). Depressive disorder is the most frequent diagnosis in both sexes, followed by alcohol and drug abuse in men, and anxiety disorders in women. Comorbidity is frequent, especially between psychiatric disorder and personality disorder.

Motivation and deliberate self-harm

The motives for DSH are usually mixed and often difficult to identify with certainty. Even when patients know their own motives, they may try to hide them from other people. For example, people who have taken an overdose in response to feelings of frustration and anger may feel ashamed and say instead that they wished to die. Conversely, people who truly intended to kill themselves may deny it. For this reason, when individuals are assessed, more emphasis should be placed on a common-sense evaluation of their actions leading up to self-harm than on their subsequent accounts of their motives.

Table 16.5 Reasons given for deliberate self-harm

From Hawton K and Taylor T (2009). Treatment of suicide attempters and prevention of suicide and attempted suicide. In: Gelder MG, Andreasen NC, López-Ibor JJ Jr and Geddes JR (eds). The New Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Despite this limitation, useful information has been obtained by questioning groups of patients about their motives. Indeed, a study in 13 European countries found similar reported motives in all of the study sites (Hjelme-land et al., 2002). The motives are listed in Table 16.5. Only a few patients stated that the act was premeditated. About 25% said that they wished to die. Some stated that they were uncertain whether they wanted to die or not, others that they were leaving it to ‘fate’ to decide, and yet others that they were seeking unconsciousness as a temporary escape from their problems. Another group admitted that they were trying to influence someone—for example, that they were seeking to make a relative feel guilty for having failed them in some way. This motive of influencing other people was first emphasized by Stengel and Cook (1958), who wrote that these people hoped to call forth ‘action from the human environment.’ This behaviour has since been referred to as ‘a cry for help.’ Although some acts of DSH result in increased help for the patient, others may arouse resentment, particularly when they are repeated.

The outcome of deliberate self-harm

Repetition of self-harm

In the weeks after DSH, many patients report changes for the better. Those with psychiatric symptoms often report that they have become less intense. This improvement may result from help provided by professionals, or from improvements in the person’s relationships, attitudes, and behaviour. Some people do not improve and harm themselves again, in some cases fatally. A systematic review of 90 studies (Owens et al., 2002) concluded that among people who have engaged in DSH:

• about one in six repeats the DSH within 1 year

• about one in four repeats the DSH within 4 years.

Factors associated with repetition of DSH (Appleby, 1993) are listed in Table 16.6.

Suicide following deliberate self-harm

People who have intentionally harmed themselves have a much increased risk of later suicide. The same systematic review (Owens et al., 2002) concluded that among these people:

• between 1 in 200 and 1 in 40 commit suicide within 1 year

• about 1 in 15 commits suicide within 9 years or more.

These risks are compiled from several countries, so they cannot be compared directly with the general population rate of about 1 in 10 000 people per annum in the UK. Nevertheless, the risk is clearly greatly increased.

Among people who deliberately harm themselves, the risk of eventual suicide is even greater among those who are older, male, depressed, or alcohol dependent. Use of a dangerous or violent method also indicates a high risk. However, a non-dangerous method of self-harm does not necessarily indicate a low risk of subsequent suicide, partly because the patient may have incomplete knowledge of the dangerousness of the available methods.

It is difficult to predict which patients will die by suicide following previous self-harm, because the rate of suicide, although higher than that in the general population, is still quite low, and the predictive factors have low specificity. Although it was designed to assess immediate suicide risk, the Beck Suicide Intent Scale (Beck et al., 1974) is of some value in assessing suicide risk during the first year following the original self-harm (Harris et al., 2005).

Table 16.6 Factors associated with risk of repetition of attempted suicide

From Hawton K and Taylor T (2009). Treatment of suicide attempters and prevention of suicide and attempted suicide. In: Gelder MG, Andreasen NC, López-Ibor JJ Jr and Geddes JR (eds). The New Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Results of treatment after deliberate self-harm

Although randomized controlled studies have shown decreases in psychopathology and improvements in social problems after various treatments, there is less evidence that treatment prevents the repetition of DSH. One reason for this lack of evidence is that different kinds of treatment have been investigated, and the numbers in most studies have been rather low. Hawton conducted a meta-analysis of 20 randomized controlled trials (of 10 different interventions), with repetition of DSH as an outcome measure. He subsequently reviewed the treatments used in greater depth (Hawton, 2005). His conclusions were as follows.

• A trend towards greater reduction of repetition was found for problem-solving therapies, although this was only statistically significant in one out of six randomized controlled trials. One study that used a self-help manual found no benefit.

• Brief psychodynamic interpersonal therapy has been shown in one randomized controlled trial to reduce self-reported attempts at self-harm more than treatment as usual (Guthrie et al., 2001).

• For patients with borderline personality disorder, rates of repetition were lower with dialectical behaviour therapy than with standard aftercare (based on a single trial).

• The provision of emergency contact cards (allowing immediate access to help) showed some benefits, but not in all studies and probably only for first attenders. There was some suggestion that such cards may be detrimental for repeat attenders.

• The provision of increased intensity of care with out-reach showed modest benefit, but only for the home visit/outreach component.

An Australian study showed some benefit, in terms of decreased repetition rates, from sending a series of postcards to patients over a 12-month period after an episode of self-harm (Carter et al., 2007). However, this was not confirmed by a similar study in New Zealand (Beautrais et al., 2010).

Special groups

Mothers of young children

Mothers of young children require special consideration because of the known association between DSH and child abuse. It is important to ask about the mother’s feelings towards her children, and to enquire about their welfare. In the UK, information about the children can usually be obtained from the general practitioner, who may ask their health visitor to investigate the case.

Children and adolescents

DSH among children and adolescents increased in the 1990s in many parts of the developed world. It is difficult to obtain the exact rates because many of these acts are minor drug overdoses or self-injuries that do not reach the medical services (Hawton et al., 2002). It is generally agreed that DSH is rare among preschool children, and becomes increasingly common after the age of 12 years. Except in the youngest age groups, it is more common among girls.

Methods. Drug overdose is the most common method among those attending hospital. Self-cutting is common, especially among females, although it less often results in attendance at hospital. More dangerous forms of self-injury are more frequent among boys (Hawton et al., 2003c).

Motivation. It is difficult to determine the motivation for self-harm in young children, especially as a clear concept of death is not usually developed until around the age of 12 years. It is probable that only a few younger children have any serious suicidal intent. Their motivation may be more often to communicate distress, to escape from stress, or to influence other people. Epidemics of DSH occasionally occur as a result of imitative behaviour among adolescents in psychiatric hospitals and other institutions (de Wilde, 2000).

Causes. DSH in adolescents is associated with family breakdown, familial psychiatric disorder, and child abuse, or simply not feeling ‘heard’ or validated within the family environment (Sinclair and Green, 2005). It is often precipitated by social problems—for younger adolescents most often family problems, for older ones difficulties with boy- or girlfriends, and for both age groups problems with schoolwork. Among adolescents it is also associated with alcohol and drug misuse (especially among males), violence and being the victim of violence, mood disorder, and personality disorder (Hawton et al., 2003c).

Outcome. For most children and adolescents, the outcome of DSH is relatively good, but a significant minority continue to have social and psychiatric problems, and to repeat acts of DSH. A poor outcome is associated with poor psychosocial adjustment, a history of previous DSH, and severe family problems.

Management. When children or adolescents harm themselves, it is better for them to be assessed by child and adolescent psychiatrists rather than members of the adult DSH service. Treatment usually involves the family, and is directed to the causal problems and to the coping skills of the child or adolescent.

The management of deliberate self-harm

The organization of services

The care of DSH patients involves a variety of services, including primary care teams, ambulance services, emergency department staff, and social services. All of these staff require training to enable them to respond appropriately and to make the necessary decisions, including how to assess immediate risk, to obtain informed consent, and to assess capacity to consent and in what circumstances necessary care can be given without consent. The organization of the medical and surgical response to these patients is beyond the scope of this book; for such information, see National Institute for Clinical Excellence (2004b).

Arrangements for psychosocial assessment vary. Whatever arrangement is made, it is important to ensure that all patients receive a psychosocial assessment as well as an assessment of the medical effects of the self-harm (see below). Each hospital site should have a code of practice detailing the arrangements for psychosocial assessment agreed by general medical and psychiatric services and known to those who work there.

Facilities should be available for the special needs of patients from ethnic minorities. Children and adolescents should whenever possible be assessed by staff who have been trained in the assessment and care of young people and who are familiar with the problems of confidentiality and consent that can arise in such cases. If possible, patients over the age of 65 years should be assessed by staff who are familiar with the special problems of the elderly, and who are aware of the greater risk of completed suicide in this age group.

The assessment of patients after deliberate self-harm

General aims

Assessment is concerned with three main issues:

1. the immediate risks of suicide

2. the subsequent risks of further DSH

3. current medical or social problems.

The assessment should be conducted in a way that encourages patients to undertake a constructive review of their problems and of the ways in which they could deal with them themselves. It is important to encourage self-help, because many of these people are unwilling to be seen again by a psychiatrist.

Usually the assessment has to be carried out in an Accident and Emergency department or a ward in a general hospital, where there may be little privacy. Whenever possible, the interview should be conducted in a side room so that it will not be overheard or interrupted. If the patient has taken an overdose, the interviewer should first make sure that they have recovered sufficiently to be able to give a satisfactory history. If consciousness is still impaired, the interview should be delayed. Information should also be obtained from relatives or friends, the family doctor, and any other person (such as a social worker) who is already attempting to help the patient. Wide enquiry is important, as sometimes information from other sources may differ substantially from the account given by the patient. For a review of general hospital assessment, see Hawton (2000b).

Specific enquiries

The interview should address five questions.

1. What were the patient’s intentions when they harmed themself?

2. Do they now intend to die?

3. What are their current problems?

4. Is there a psychiatric disorder?

5. What helpful resources are available?

Each of these questions will now be considered in turn.

What were the patient’s intentions when they harmed themself?

Patients sometimes misrepresent their intentions. For this reason the interviewer should reconstruct, as fully as possible, the events that led up to the act of self-harm in order to find the answers to five subsidiary questions.

• Was the act planned or carried out on impulse? The longer and more carefully the plans have been made, the greater is the risk of a fatal repetition.

• Were precautions taken against being found? The more thorough the precautions were, the greater is the risk of a further fatal overdose. Of course, events do not always take place as the patient expected—for example, a partner may arrive home earlier than usual so that the patient is discovered alive. In such circumstances it is the patient’s reasonable expectations that are of importance in predicting the future risk.

• Did the patient seek help? Serious intent can be inferred if there were no attempts to obtain help after the act.

• Was the method thought to be dangerous? If drugs were used, what were they and what amount was taken? Did the patient take all of the drugs available? If self-injury was used, what form did it take? Not only should the actual dangerousness of the method be assessed, but also the dangerousness anticipated by the patient, which may be inaccurate. For example, some people wrongly believe that paracetamol overdoses are harmless, or that benzodiazepines are dangerous.

• Was there a ‘final act’ (e.g. writing a suicide note or making a will)? If so, the risk of a further fatal attempt is greater.

By reviewing the answers to these questions, the interviewer can form a judgement of the patient’s intentions at the time of the act (see Table 16.7).

Table 16.7 Factors that suggest high suicidal intent

From Hawton K and Taylor T (2009). Treatment of suicide attempters and prevention of suicide and attempted suicide. In: Gelder MG, Andreasen NC, López-Ibor JJ Jr and Geddes JR (eds). The New Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

A similar approach has been formalized in Beck’s Suicide Intent Scale.

Do they now intend to die?

The interviewer should ask directly whether the patient is pleased to have recovered or wishes that they had died. If the act suggested serious suicidal intent and if the patient now denies such intent, the interviewer should try to find out by tactful questioning whether there has been a genuine change of resolve.

What are their current problems?

Many patients will have experienced a mounting series of difficulties in the weeks or months leading up to the act. Some of these difficulties may have been resolved by the time that they are interviewed, sometimes as a result of the act of self-harm—for example, a partner who had threatened to leave the patient may have decided to stay. The more serious the problems that remain, the greater is the risk of a fatal repetition. This risk is particularly strong if the problems include loneliness or ill health. The review of problems should be systematic and should cover the following:

• intimate relationships with the partner or another person

• relationships with children and other relatives

• employment, finances, and housing

• legal problems

• social isolation, bereavement, and other losses

• physical health.

Drug and alcohol problems can be considered either at this stage of the assessment or later when the psychiatric state is reviewed.

Is there a psychiatric disorder?

It should be possible to answer this question from the history and from a brief but systematic examination of the mental state. Particular attention should be directed to depressive disorder, alcoholism, anxiety disorder, and personality disorder. Schizophrenia and dementia should also be considered, although they will be found less often. Adjustment disorders are diagnosed in many individuals in response to major life changes and stresses (e.g. bereavement, relationship break-up, migration). The presence of an obvious precipitating event does not rule out the presence of a psychiatric disorder.

What helpful resources are available?

These include capacity to solve problems, material resources, and the help that others are likely to provide. The best guide to patients’ ability to solve future problems is their record of dealing with difficulties in the past—for example, the loss of a job or a broken relationship. The availability of help should be assessed by asking about friends and confidants, and about any support the patient is receiving or can be expected to receive from the general practitioner, social workers, or voluntary agencies.

Is there a continuing risk of suicide?

The interviewer now has the information required to answer this important question. The answers to the first five questions outlined above are reviewed:

• Did the patient originally intend to die?

• Do they intend to do so now?

• Are the problems that provoked the act still present?

• Is there a psychiatric disorder?

• Is additional support available, and is the patient likely to accept it?

Having reviewed the answers to these questions, the interviewer compares the patient’s characteristics with those that are found in people who have died by suicide. These characteristics are summarized in Table 16.7.

Is there a risk of further non-fatal self-harm?

The predictive factors are summarized in Table 16.6. The interviewer should consider all of the points before deciding on the risk.

What treatment is required and will the patient agree to it?

If the risk of suicide is judged to be high, the procedures are those outlined in the first part of this chapter (see p. 428). Around 5–10% of DSH patients require admission to a psychiatric unit; most need treatment for depression or alcoholism, and a few for schizophrenia. Some need a period of respite from overwhelming stress.

If admission to hospital is not indicated, a plan of management has to be agreed with the patient and any potential carers. If the patient refuses the offer of help, their care should be discussed with the general practitioner before they are allowed to return home (see below and Box 16.1). For some patients it is useful to provide an emergency telephone number that allows immediate access to advice or an urgent appointment should there be a further crisis.

Management after the assessment

Patients who have harmed themselves are often reluctant to accept further help, and it is important to conduct the assessment interview in a way that fosters a therapeutic relationship. Plans should be discussed with the patient, and if they are not agreed, an alternative plan that is mutually acceptable should be negotiated. Patients’ needs fall into three groups:

1. a small minority need admission to a psychiatric unit for treatment

2. about one-third have a psychiatric disorder that requires treatment in primary care, or from a psychiatric team in the community

3. the remainder need help with various psychosocial problems, and assistance with improving their ways of coping with stressors. This help is needed even when the risk of immediate suicide or non-fatal repetition is low, as continuing problems increase the risk of later repetition. Apart from practical help, problem solving is usually the best approach, starting with the problems identified during the assessment interview. Unfortunately, such help is often refused.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree