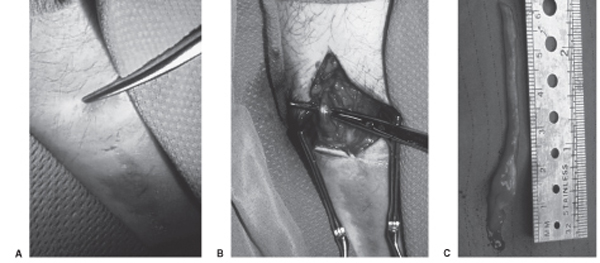

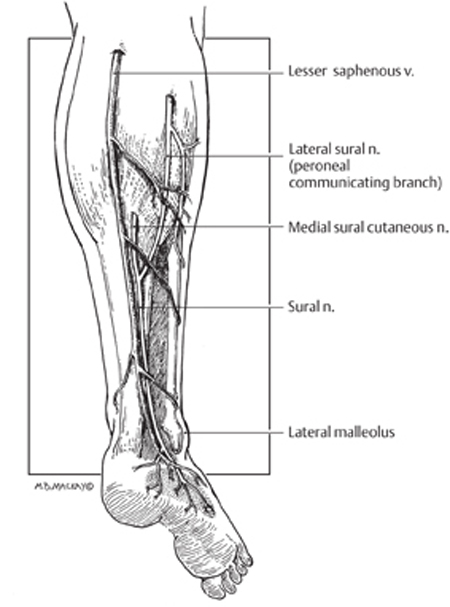

45 Sural Nerve Injury and Neuroma A 45-year-old male with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated painful peripheral neuropathy had previously undergone sural nerve biopsy. He had a zone of sensory loss, corresponding to the usual distribution of the sural nerve. One year postbiopsy, he developed onset of severe sharp and stabbing pain along the scar, with a trigger point and palpable subcutaneous mass proximal to the incision (Fig. 45–1A). The pain was intractable to medications, including tricyclic agents that were partially effective for his generalized painful peripheral neuropathy. At surgery, an end stump neuroma was observed (Fig. 45–1B). The neuroma and a generous length of sural nerve proximal to it were removed (Fig. 45–1C). The remaining sural nerve stump was coagulated and buried deep to the fascia proximal to the incision. The patient had immediate pain relief, which has been maintained over a follow-up of 12 months to date. Sural nerve neuroma Figure 45–1 Operative photomicrographs from this case. (A) The instrument points to the trigger point and palpable subcutaneous mass 2 cm proximal to the prior sural nerve biopsy incision. (B) Deep to this, in subcutaneous tissue, an end stump neuroma was discovered and (C) resected, along with a considerable length of proximal sural nerve. The sural nerve carries primarily S1 sensory fibers, receiving branches from the posterior tibial (medial sural) and peroneal (lateral sural) nerves in the popliteal fossa. There is one contribution from each in ˜80% of cases. In the remainder, the sural nerve arises exclusively from the posterior tibial but occasionally from the peroneal alone. The sural branch from the tibial lies between the two heads of the gastrocnemius muscle, deep to the fascia. However, the lateral sural (also called the peroneal communicating branch) is superficial to the gastrocnemius fascia and at times may arise in common with another cutaneous branch from the peroneal, the cutaneous peroneal nerve. The medial sural nerve descends deep to the gastrocnemius fascia in the proximal lower leg running in the posterior midline. It emerges from the fascia into the subcutaneous plane about halfway down the leg, an average of 16 cm proximal to the lateral malleolus. Shortly after the emergence from the fascia, there is an anastomosis with the lateral sural nerve found in 75 to 84% of cadaveric dissections. From here the combined sural nerve pursues a slightly oblique course from the initial midline position to lie posterior to the lateral malleolus and anterior to the Achilles tendon (Fig. 45–2). In this oblique location, the nerve is closely related to the small saphenous vein, which serves as an excellent landmark for finding the nerve. Just above the ankle level, the nerve starts to branch. The standard zone of sensory innervation (and sensory loss following injury, biopsy, or nerve harvesting) is to the dorsal lateral foot (Fig. 45–2). Figure 45–2 Schematic of sural nerve anatomy. The sural nerve, with the contributions from the tibial (medial sural) and peroneal (lateral sural or peroneal communicating branch) nerve, is outlined, along with the relationships of the nerve to the lesser saphenous vein and lateral malleolus. The typical sensory zone of sural nerve innervation is illustrated (stippling) Sural nerve mononeuropathy is most commonly secondary to trauma, either surgical or accidental. The sural nerve may be injured from laceration by glass, knives, or lawn-mower blades, or as a result of blunt injury with concomitant ankle and calcaneal fractures. The occasional patient is seen following industrial accidents, especially from a high-pressure water jet type of trauma. Chronic injury may occur from tightly laced, high-topped footwear. Iatrogenic circumstances leading to sural nerve injury include vein stripping, Baker cyst surgery, calf muscle biopsy, and orthopedic procedures in the popliteal area or lateral ankle region. Biopsy or harvesting of the sural nerve leading to a painful neuroma formation is reported with a variable incidence, ranging from rare in one large series of nerve grafting, to a 6% and up to a 16% incidence in some series. Finally, the nerve may be entrapped by scar or congenital adhesions, compressed by a Baker cyst, or may be involved in a ganglion cyst. There are many causes of leg pain, especially following injury, that are more common than a painful neuroma. Pain may arise from damage to other soft tissue structures (muscles, ligaments, and tendons). Malunited and nonunited fractures may result in intractable pain, as can chronic irritation of soft tissue from implanted hardware. Inflammatory conditions, such as arthritis in the ankle joint, tendonitis, and fasciitis need to be entertained. There may be coexistent damage to more than one peripheral nerve. Some patients may have a more proximal nerve injury (lumbar plexus) or S1 radiculopathy that may masquerade as a sural nerve problem. In some patients, the pain may have a multifactorial basis. Finally, secondary gain and psychogenic issues have to be considered. The diagnosis of sural nerve injuries is clinically obvious in the majority of cases. There is often a history of preceding injury, surgery, or trauma. The patient invariably presents with a painful condition and often reports sensory alteration in the nerve distribution. The examiner can easily assess the location of previous injury in relation to the known anatomical course of the sural nerve. Occasionally, a neuroma may be palpable at or adjacent to the site of previous trauma or surgery (as in this case). The nerve may also be hyperirritable adjacent to the area of injury, and often proximal and sometimes distal to this as well, with paresthesias evoked along the distal distribution of the nerve evoked by percussing or palpating over the injured nerve segment. Nerve conduction studies may be useful in the diagnosis of sural nerve injuries. On careful evaluation, the electrodiagnostician may find a complete loss of response or discern prolonged sensory latency or decreased amplitude. It is important to compare the affected side with the normal leg for control purposes. The response to one or a series of nerve blocks may be diagnostic in uncertain cases. An intermediate-duration local anesthetic, such as 0.50% bupivacaine (Marcaine, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, Wilmington, DE) is instilled in the area of the trigger point, adjacent to the nerve in sufficient volume (5 to 10 mL) to obtain effective local anesthetic blockade of the nerve. The patient is then asked to monitor the degree of pain carefully and report back in 1 week. Elimination or substantial relief of the pain for greater than 24 hours (which exceeds the duration of local anesthetic action) is graded as a positive response. If effective relief can be confirmed on a second, or possibly third, procedure, then a relatively high degree of confidence is achieved that the area of previous nerve injury is in fact the main peripheral source of the patient’ s painful condition. In cases where uncertainty still exists or more objective evidence is needed, one may entertain a blinded placebo block to confirm the diagnosis. The majority of these patients have a painful neuropathic condition. Sensory loss is not clinically important. In this circumstance, the goal is to eliminate the patient’ s pain problem. The initial approach is almost always conservative. This entails watchful waiting because many patients achieve an acceptable pain control over the course of time. The patient is referred to a physiotherapist and undergoes therapy and other physical modalities of treatment. Often this alone will control the pain syndrome to an acceptable level. Many of these patients have already gone to a pain clinic and tried various medications. If not, a course of tricyclic agents is worthwhile. I usually begin with amitriptyline (Elavil, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, Wilmington, DE) 25 mg at night (10 mg in geriatric patients) and ask the patient to increase this to 50 mg per night after 3 weeks, if required. It is stressed to the patient that a 6- to 8-week trial of tricyclics is needed before they can be abandoned for not providing significant pain relief. Other medications that are occasionally beneficial include anticonvulsant agents such as carbamazepine (Tegretol, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp., East Hanover, NJ), phenytoin (Dilantin, Pfizer, Inc., New York, NY), and gabapentin (Neurontin, Pfizer, Inc., New York, NY) as well as newer generation non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as ketorolac (Toradol, Roche Pharmaceuticals, Nutley, NJ). In many of these patients, as in this case, the presence of a neuroma along the sural nerve at or adjacent to the injury site is clinically obvious. In other patients, this is not so clear, and a series of nerve blocks (as discussed earlier) is extremely helpful in determining whether a peripheral trigger source of pain is present, and more importantly if it may respond to a surgical peripheral nerve procedure. Occasionally, a series of nerve blocks will achieve sufficient pain control on their own to obviate the need for surgery. For those patients with an obvious painful neuroma, and others with a painful nerve injury not responding to conservative treatment, especially where a nerve block has been successful in ameliorating pain, a peripheral nerve surgical procedure is warranted. There are three general procedures available for painful cutaneous nerve injury conditions: neurolysis, nerve repair (grafting), and neurectomy. Neurolysis carries the benefit of no loss of sensory function (if, in fact, this is retained postinjury). It appears to achieve reasonable results where the nerve is primarily entrapped and not injured. However, the results of neurolysis have been poor for long-term pain control of lower-extremity cutaneous nerve injuries. Nerve grafting has some theoretical merit, in that regenerating axons can be directed away from the zone of nerve injury and scar. However, patients have been reported who then develop a neuroma within the suture line, resulting in an equally intractable recurrence of pain. Also, grafting requires harvesting of a donor nerve, and this has obvious drawbacks. The most reliable procedure remains a neurectomy. The patient must accept the trade-off: loss of sensory function for probable relief of pain. The sural nerve does not supply sensation to a critical area so that the sensory deficit is well tolerated. My personal procedure of choice for painful sural nerve injury is neurectomy. The principle is that one is operating or doing surgery on a painful neuroma. Thus I recommend wide excision of the damaged nerve. The proximal stump is placed well away from the zone of injury, preferably deep within healthy subcutaneous tissue or muscle. The proximal stump is also coagulated, and depending on circumstances, I consider burying it within muscle or even adjacent to bone. However, there is no absolute guarantee against reformation of a painful neuroma. The regenerative capacity of a peripheral nerve is quite great and despite all means, the axons from the proximal nerve stump may regenerate. A variable percentage of patients may require a second or even a third operation on the painful neuroma. Electrical stimulation of a painful neuroma (Chapter 57) is another reasonable option for managing this patient population. Finally, there is a minority of patients with a painful sural nerve injury whose main pain generator is not in the periphery but is more central. These patients essentially have a deafferentation pain syndrome. As a rule, these patients will not benefit from a peripheral procedure and require a central procedure such as a dorsal column stimulator for effective pain control. Sural nerve injuries often produce a severe pain syndrome, usually refractory to conservative management. The diagnosis is often clinically obvious with the appropriate history and may be aided by the presence of a palpable neuroma and sensory alteration in the nerve distribution. The positive response to a series of nerve blocks will help ascertain the diagnosis in uncertain cases. When a peripheral source of pain can be documented, then wide neurectomy of the injured sural nerve or neuroma is often successful in controlling the patient’ s pain problem.

Case Presentation

Case Presentation

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Anatomy

Anatomy

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Diagnostic Tests

Diagnostic Tests

Electrodiagnostic Studies

Nerve Blocks

Management Options

Management Options

Conclusions

Conclusions

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree