26 The craniovertebral junction (CVJ) is the part of the neuraxis from the foramen magnum to the vertebra of the atlas and axis. The neural elements encompassed by these bones include the medulla, the cervicomedullary junction, and the upper cervical spinal cord. Many abnormalities can affect this biomechanically and anatomically complex part of the spine. These include bony structural defects, acquired and congenital mechanical dysfunction, mass lesions such as tumors and inflammatory lesions, and intrinsic neural lesions. Lesions in this area can be difficult to diagnose as they may produce both local and remote symptoms; they can also be difficult to treat surgically as their inherently deep location and complex local anatomy challenge the approach. Originally, CVJ tumors were treated by simple posterior decompression with or without fusion, a practice that resulted in overall poor outcomes. At the same time, wide resection as a treatment for malignant tumors was not well appreciated. This created pessimism about CVJ tumors. Surgery for diagnosis and palliation has slowly been replaced by surgery for treatment and stabilization.1 Advances in our understanding of this region, based on studies from many surgical subspecialties, have ushered in new treatment options. As a result, tumors that were previously unresectable due to access issues are now treatable. This chapter presents an overview of the clinical features of CVJ tumors and surgical techniques to approach and fix the CVJ. Tumors found at the CVJ arise from neural tissues (schwannomas, neurofibromas, astrocytomas, ependymomas), their coverings (meningiomas, arachnoid cysts), or local bone and soft tissue (chordomas, osteomas, osteoblastomas, giant cell tumors, aneurysmal bone cysts, plasmacytomas, eosinophilic granulomas, metastases).2,3 The most common intradural extramedullary tumors are meningiomas, neurofibromas, and schwannomas.4 In a review of 133 cases, 75% of intradural extramedullary foramen magnum tumors were meningiomas and 13% were neurofibromas.5 However, these meningiomas represent only 0.3 to 3.2% of all meningiomas.6 Rarely, teratomas, lipomas, arachnoid cysts, paragangliomas, and dermoids have been reported. Intradural intramedullary lesions include astrocytomas, ependymomas, cerebellar hemangioblastomas, medulloblastomas, and choroid plexus papillomas. Extradural lesions are usually metastases, chondromas, and chordomas of the clivus (Table 26-1).

Surgical Approaches for Decompression and Fixation of the Craniovertebral Junction

Tumors of the Craniovertebral Junction

Tumors of the Craniovertebral Junction

| Meningiomas Schwannomas Neurofibromas Chordomas Chondrosarcomas Epidermoids Metastases |

Clinical Features

Clinical Features

Tumors at the CVJ can present with many different clinical findings, including dysfunction of the brainstem, cranial nerves, cervical cord, cervical roots, and their vasculature (Table 26-2). Tumors at the CVJ can be mechanically destabilizing, resulting in basilar impression, cranial settling, and atlanto-occipital instability.7 Symptoms are usually insidious and may present as a clinically puzzling condition because of false localizing signs.8 Symptoms may mimic nonneoplastic processes such as cervical spondylosis, carpal tunnel, multiple sclerosis (MS), infection, cervical hemicord lesion, and inflammatory lesions.9–11

The classic clockwise progression of motor deficits from the ipsilateral arm to leg followed by the contralateral leg to arm was reported with slow-growing tumors in the older literature,12 but not as much in later studies.3,11 CVJ tumors are associated with constant neck stiffness/pain, lower cranial nerve dysfunction, upper extremity weakness and atrophy, ataxia and dysmetria, gait disturbances, paresthesias of the extremities, pyramidal tract findings, and spastic gait.9 Pain is usually around the second cervical dermatome or suboccipital region. Much literature is dedicated to the neurologic findings arising from tumors of the jugular foramen involving every combination of lower cranial nerves and sympathetics. The most common motor symptoms are weakness and hand clumsiness associated with spasticity.13 Myelopathy is a common neurologic finding, observed in more than 90% of patients in one series.14 Another syndrome of neck pain, hand weakness and atrophy, and leg stiffness has been described with cervicomedullary lesions.15 Bladder incontinence is unusual; urgency and hesitancy is more common. Hearing loss, vertigo, dysphagia, and dysarthria are less common. Respiratory arrest and apnea may explain the rare cases of rapid deterioration and death.16

|

Surgical Approaches to the Craniovertebral Junction

Surgical Approaches to the Craniovertebral Junction

The CVJ can be approached from five general directions: anterior, anterolateral, lateral, posterolateral, and posterior. The direct anterior approaches include the transoral approach and its variations. The anterolateral approaches include the mandibular swing transcervical and extrapharyngeal transcervical approach. The lateral transcervical approach is a direct approach to the vertebral artery. Posterolateral approaches include the far/extreme lateral transcondylar approach and the posterolateral approach. Finally, the ubiquitous midline posterior approach is used as a direct posterior approach to the CVJ.

Transoral Transpharyngeal Approach

Fang and Ong17 introduced the direct transoral approach to the CVJ in 1962. Despite high morbidity and technical complications, the potential of this direct approach was not lost on many who continued to extend and improve this technique.18–23 Tracheostomy is now rarely required since the introduction of flexible orotracheal tubes.24 The McGarver and Crockard retractors and the operative microscope have facilitated the technique. More recent developments include extending the approach down to C4 without tongue splitting,24 image-guided stereotactic navigation for more controlled surgery,25–27 intraoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to improve tumor resection,28 and endoscopes to improve the view without additional osteotomies.29 However, the high incidence of postoperative meningitis associated with intradural lesions continues to the present day.30–32

The transoral transpharyngeal approach, also known as the buccopharyngeal approach, can expose the inferior third of the clivus down to the C2 vertebral body. Its primary indication is for midline extradural lesions that compress the anterior brain stem and upper cervical spine. Though the superior and inferior extent of the exposure can be quite wide, this approach can only extend 1 to 1.5 cm laterally to either side of the midline as the vertebral artery and eustachian tube may be injured.

The transoral approaches travel across an inherently contaminated area; thus, an active nasopharyngeal infection raises the risk of infection to unacceptable levels. Routine preoperative nasal cultures may20,33 or may not34 be done. In addition, vascular structures within or anterior to the lesions can prevent this approach, as vascular control is limited. Treatment of intradural lesions continues to be avoided by this approach due to the frequent inability to achieve a watertight dural closure.6,35–39 A jaw opening of less than 25 mm or severe malocclusion may preclude this approach or require an ear, nose, and throat (ENT) consultation. Palatal sectioning can improve the trajectory but results in oropalatal dysfunction postoperatively.

Postoperative spine instability is expected.34,40,41 More than two thirds of patients require posterior fusion after transoral surgery20,24,42 due to mechanical instability.40 Some authors, including surgeons at our institution, recommend immediate fixation,20 whereas others stage the stabilization.34

Technique

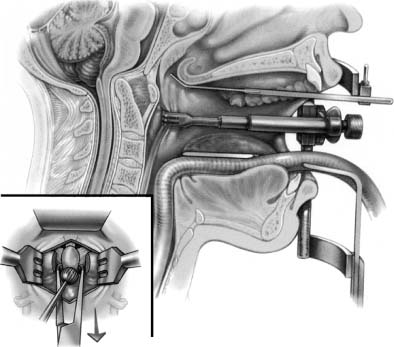

Preoperative traction to help reduce a lesion may be warranted in selected cases. The patient is placed supine with the neck in slight extension. After induction of anesthesia, the flexible fiberoptically placed orotracheal tube is retracted away from view. Rubber catheters can be placed through the nares out the pharynx and secured to retract the soft palate. The mouth is kept open with a self-retaining retractor. Frequent checks are done to avoid excessive and prolonged compression of the soft tissues. The anterior C1 arch can be palpated through the posterior pharyngeal wall and verified with fluoroscopy. The posterior pharyngeal wall is incised in the midline at this point. The mucosa and prevertebral muscles are elevated as a mucoperiosteal layer by subperiosteal dissection. The mucoperiosteal layers are spread with a self-retaining retractor to a maximum of 1.5 cm to either side (Fig. 26-1). The soft palate can be split at the midline to extend superior and lateral exposure. The longus and capitis muscles and the anterior longitudinal ligament are dissected free, exposing the inferior clivus and arch of C1. A high-speed pneumatic drill is used to remove the arch of C1 and the odontoid process. Dens removal can be facilitated by detaching the anchoring ligaments. The thecal sac is identified by its pulsations. Bony dissection can be continued down to C2. Throughout, care must be taken to avoid the lower cranial nerves, the carotid artery, and the jugular vein, all of which can be encountered. Any dural opening must be closed, however difficult. Before closing, a fat graft is placed in the resection bed. The mucosa and posterior pharyngeal tissue are closed with interrupted absorbable sutures. Postoperatively, soft tissue swelling is expected, as is its resolution with time. Enteral nutrition may be required via feeding tube if oral nutrition is not possible. Posterior stabilization is performed as soon as possible.

FIGURE 26-1 Cross-section illustration of the transoral approach. The self-retaining oral retractor facilitates the approach. A special adapter has retracted the soft palate superiorly. A midline retractor is spreading the posterior pharyngeal wall. (Inset) The anterior exposure allows decompression at the level of the dens. (Courtesy of the Barrow Neurological Institute.)

Transoral Translabiomandibular Transpharyngeal Approach

Efforts to enlarge the operative space, to extend the exposure, and to apply the transoral approach to patients with anatomic limitations such as a small mouth opening or malocclusion have resulted in “complex” transoral approaches. To extend the inferior exposure of the transoral approach further, several authors have described splitting the mandible. The tongue is left intact and depressed inferiorly or is divided at the midline and split with the mandible halves.13,19,22,33,43–45 Due to more extensive oropharyngeal swelling, a tracheostomy is frequently required.

The transoral translabiomandibular approach can expose the inferior third of the clivus down to the upper cervical vertebral bodies more caudally than the standard transoral approach. Splitting the mandible also provides a larger surgical working space.46 All transoral approaches carry the same general indications, contraindications, and complications; however, the risk of wound infection is increased with this approach. This approach also carries the additional risk of malocclusion, more severe swallowing difficulties, dysphonia, and tongue dysfunction.

Technique

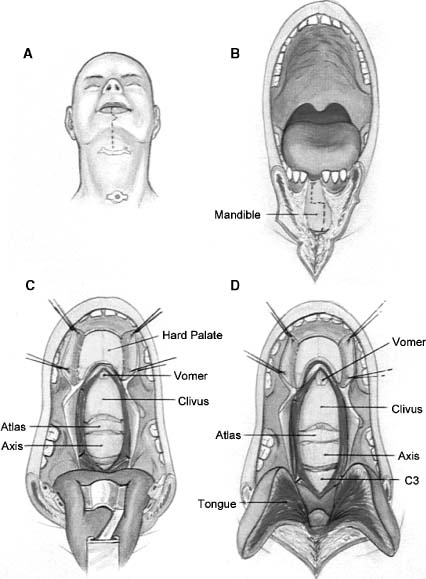

The general considerations for transoral surgery apply. Preoperative dental evaluation is recommended. A feeding tube is placed at the time of anesthesia to avoid later difficulties due to potential pharyngeal swelling. The patient is placed supine with the neck in slight extension. The entire jaw, oropharynx, and upper neck is prepared and exposed. The lower lip is incised with a zigzag incision (Fig. 26-2). A mucosal incision is made at the alveolar margin under the lower lip. The mandible is exposed by subperiosteal dissection laterally to about the mental foramen. It is paramount that jaw realignment be as accurate as possible. To this end, miniplates should be prebent and fitted and screw holes predrilled to maximize later alignment. The mandible is then split with a staircase osteotomy. The tongue may be split in the midline if depression down between the split mandible alone is insufficient. This exposure can frequently extend exposure to the level of the arytenoids. The posterior pharyngeal wall is opened and surgery is continued as previously described. After the posterior pharyngeal wall is closed, the tongue is reapproximated and sutured, if necessary. The mandible is then reapproximated and plated. The alveolar margin is closed with absorbable suture. The lip is closed with special care to reapproximate the vermilion border. The skin is closed with interrupted sutures. Postoperatively, soft tissue swelling is expected and airway management is critical. A tracheostomy may need to be placed, and enteral nutrition is continued if extubation is prolonged. Posterior stabilization is performed as soon as possible.

FIGURE 26-2 Illustration of the transoral translabiomandibular approach. (A) The skin incision splits the lower lip and chin. (B) A staircase osteotomy improves realignment. A midline incisor may have to be removed. (C) The tongue is depressed downward between the split mandible. The soft palate has been divided. The hard palate has been exposed should additional exposure be required. (D) The tongue can also be split to further improve visualization.

Transoral Transpharyngeal Extended Maxillotomy Approach

As mandibular splitting can extend the lower limits of the transoral approach, LeFort maxillotomies can extend the upper limit of the transoral approach.13,22,33,43,47–50 Three types of maxillotomies have been described51: (1) LeFort I osteotomy followed by fracturing the maxilla and hard palate en bloc inferiorly into the oral cavity; (2) LeFort I osteotomy combined with a midline osteotomy and division of the hard and soft palate, followed by swinging both maxilla halves down and out; and (3) unilateral LeFort I osteotomy combined with a midline osteotomy of the hard palate, followed by swinging the single maxilla half down and out, attached with an intact soft palate.

The transoral approach with maxillotomies can expose the majority of the clivus down to the upper cervical vertebral bodies.46 This method does carry a greater risk of wound infection and complication. Swallowing and speech difficulties are quite frequent, especially with soft palate division. The LeFort I followed by down-fracturing can obscure the lower operative field and results in greater oropalatal morbidity and dental malocclusion. The unilateral LeFort I results in more rapid recovery of oropalatal function as it preserves the soft palate and one half of the maxilla.48 We prefer this latter technique for its lower morbidity and adequate exposure.

Technique

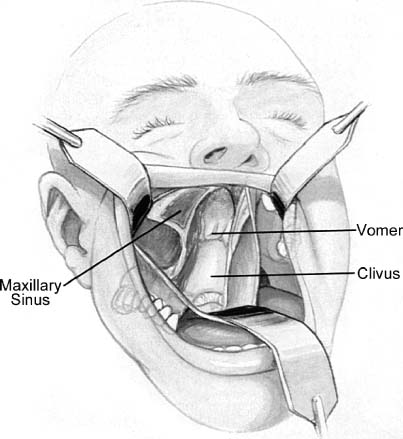

The general considerations for transoral surgery apply. A preoperative dental evaluation is recommended. After general anesthesia, a feeding tube is placed. The patient is placed supine with the neck in slight extension. The face, jaw, upper neck, and oropharynx are prepared and exposed. The mucosa is elevated off the upper alveolar margin by local anesthetic injection. A mucosal incision is made under the upper lip along the alveolar margin around to the maxillary tuberosity. This alveolar tissue is elevated subperiosteally to the level of the nasal opening. The mucosa over the hard palate is also incised in the midline and elevated. Miniplates are prebent and fitted along the maxilla and screw holes predrilled to ensure proper alignment later. A unilateral LeFort I osteotomy and a midline parasagittal osteotomy between the front two incisors through the hard palate are cut. The mobile maxillar half is separated from the pterygoid process and swung down and out laterally, still attached to the intact soft palate (Fig. 26-3). The mobile bone is retracted out of the field, exposing the posterior nasopharynx. The posterior nasal septum is removed as needed. The posterior pharyngeal wall is opened and the operation performed as previously described but with greater clival exposure. After the posterior pharyngeal wall is closed, the mobilized maxilla is replaced and plated into its original position. The hard palate mucosa is closed with absorbable suture. The nares are packed to reset the nasal septum to the midline. The sublabial mucosa is then closed with interrupted absorbable sutures. Postoperatively, care is taken to allow the nasal and oral mucosa to heal. Enteral nutrition is provided. Airway management is also critical; tracheostomy may be required until pharyngeal swelling subsides. Posterior stabilization is performed as soon as possible.

FIGURE 26-3 Illustration of the transoral extended maxillotomy approach. The posterior pharyngeal wall has been incised and retracted to illustrate the clival exposure. The open maxillary sinus is visible. A unilateral LeFort maxillotomy has been performed, and the loose maxilla has been retracted inferolaterally.

Mandibular Swing Transcervical Approach

Though the transoral approaches are direct, their limited exposure prevents the treatment of many tumors. The transcervical approaches were developed to reach the CVJ through the tissues of the neck. The mandibular swing transcervical approach combines a transpharyngeal and transcervical approach to provide a wide exposure of the posterior pharynx to treat midline and lateral lesions of the CVJ.52–56 In this approach, the mandible is split and swung outward with an upper cervical myocutaneous flap. This approach can also be extended up to the infratemporal fossa and down to the vertebral bodies of the upper cervical spine. Its wide operative field affords good vascular control.

The mandibular swing transcervical approach exposes the infralabyrinthine space, inferior clivus, anterior and lateral atlas, dens, and upper cervical vertebra.57 This approach is used to treat tumors that are too large, too lateral, or too vascular for the standard transoral approach. Further, this extensive approach is amenable to resection, reconstruction, and upper cervical fusion in one operation. Despite the excellent exposure, this is a technically challenging approach. A temporary tracheostomy is nearly always required. More common complications include lingual nerve injury, eustachian tube injuries, temporary or permanent oropharyngeal dysfunction, dysphonia, and malocclusion. For protracted recoveries, a gastrotomy may also be required.

Technique

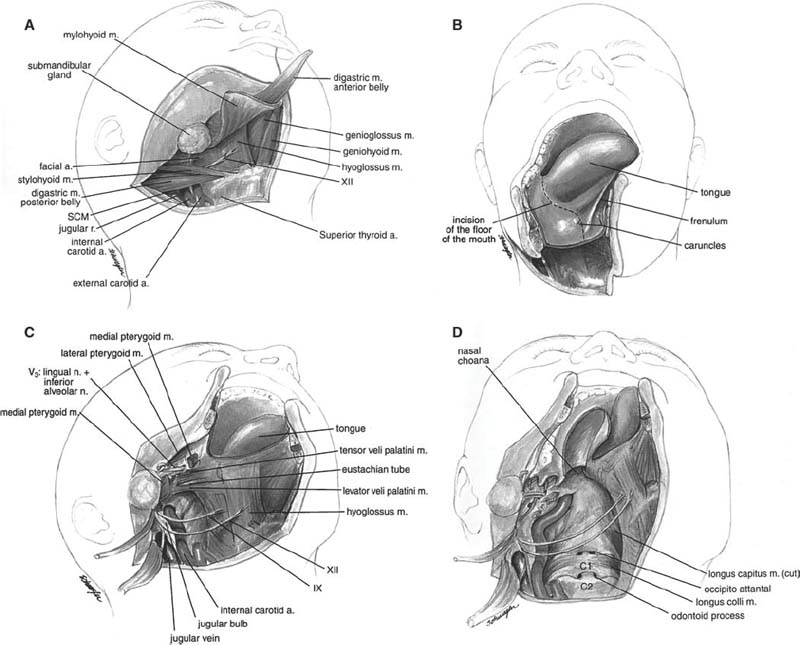

The patient is placed supine with the neck in slight extension. A tracheostomy is performed. The neck and oropharynx are prepared. A skin incision is made starting at the midline lower lip and proceeding downward to the level of the hyoid. It is extended laterally to the border of the right sternocleidomastoid muscle and turned upward along the border of the sternocleidomastoid to the mastoid process (Fig. 26-4). Subplatysmal dissection is performed to expose the submandibular gland. Dissection then proceeds underneath the submandibular gland. The sternocleidomastoid muscle is reflected outward to expose the carotid sheath. The digastric muscle is divided, followed by the mylohyoid from the hyoid and the geniohyoid from the mandible. The hypoglossal nerve should be identified and avoided. The mandible is exposed with subperiosteal dissection, and miniplates are prebent and fitted and screw holes predrilled across the midline. The mandible is divided with a staircase osteotomy. An incision is made from the midline under the tongue where the mandible has been divided and continued around the tongue to the tonsillar pillar. The tongue is retracted away from the field as the mandible half is swung out laterally with the cervical myocutaneous flap. The oropharynx and upper cervical pharyngeal space now communicate. The styloid process and its attached muscles are divided and branches of the external carotid artery ligated to enhance exposure. The lower cranial nerves should be identified. Sectioning of the soft palate, eustachian tubes, and palatini muscles can enhance the view, though these maneuvers also increase morbidity. The clivus and upper cervical spine are exposed. The posterior pharyngeal wall is incised and the anterior spine muscles retracted. Bone is removed with a high-speed pneumatic drill. Closure begins with reapproximation of the pharyngeal structures. The mylohyoid and digastric are approximated. The mandible is fixed with plates. The oral mucosa is closed with absorbable suture. The lip incision is closed with absorbable suture, taking care to align the border. The platysma and neck tissue are closed in layers.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree