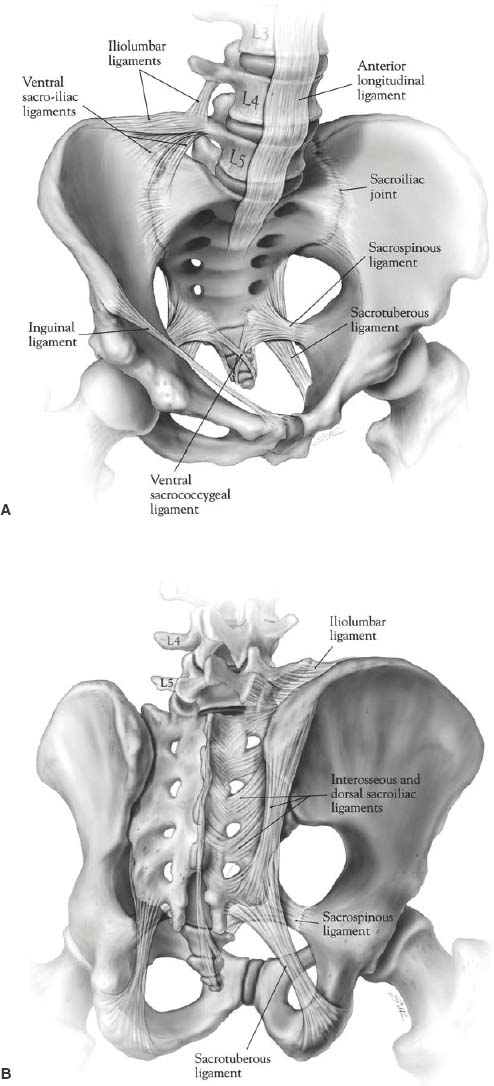

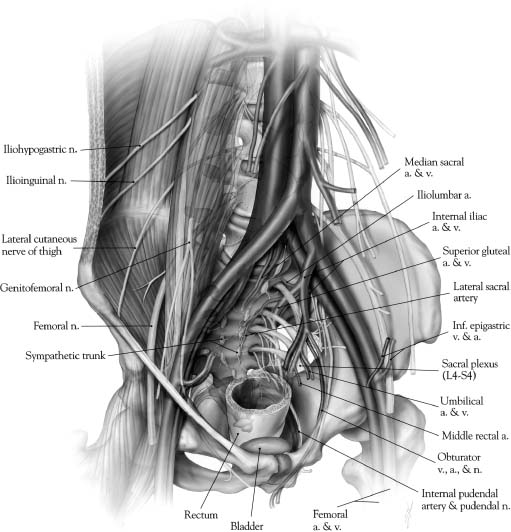

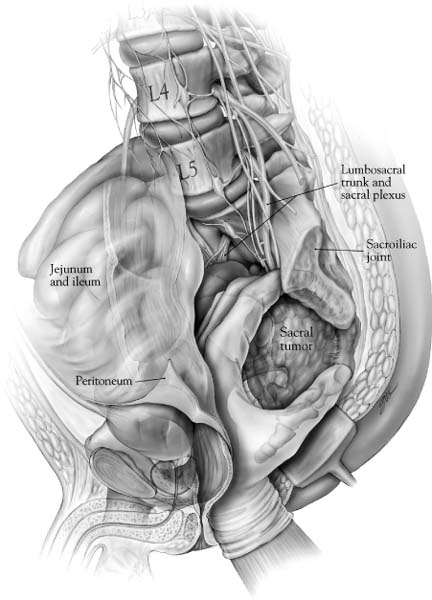

44 Tumors involving the sacrum are rare, frequently present at an advanced stage, and are often difficult to treat. Most primary neoplasms affecting the sacrococcygeal region, including chordomas, chondrosarcomas, and giant cell tumors are resistant to radiation therapy and chemotherapy. Even when these treatments are successful in the short term, rates of recurrent disease are high. Sacral resection is often the only effective alternative for possible cure in these patients.1–10 In patients with sacral invasion from advanced colorectal carcinoma or other tumors of the pelvic viscera, sacrectomy combined with rectosigmoid resection or pelvic exenteration may result in long-term disease-free survival.11 Reflecting the complex anatomy of the sacral region, aggressive resections are technically demanding procedures that often require the expertise of multiple surgical specialties (e.g., surgical oncology, neurosurgery, orthopedic surgery, vascular surgery). Long operative times and significant blood loss are common. Wide resections in this region may necessitate the purposeful sacrifice of sacral nerve roots, resulting in the loss bowel and bladder continence as well as sexual functions. In addition, high sacral amputations can disrupt spinopelvic stability, requiring advanced instrumentation techniques to reconstruct the continuity of the pelvic ring and spinal column.12 Appropriate preoperative planning and surgical technique requires a keen appreciation of the anatomic relationships of the sacral region, familiarity with the advantages and limitations of the different exposures, and a clear sense of the surgical objective. This chapter reviews the important anatomic considerations of the sacrum, including the expected functional consequences of various resections, and provides a step-by-step description of several surgical approaches for the resection of sacral tumors. The adult sacrum consists of five fused sacral vertebrae. At birth, each vertebral body is separated by an intervertebral disc. The caudal two bodies undergo fusion at approximately the 18th year of life, and the process of fusion continues rostrally until the S1-2 interspace finally fuses at the age of 25 to 30 years. The development of fused adult sacral vertebrae is dependent on normal weight bearing. The sacrum has a wedge shape due to its broad base at S1, which forms the posterior segment of the pelvic ring. The upper two or three sacral vertebrae articulate with the ilium on either side. Rostrally, the sacrum articulates with the lowest lumbar vertebra. Caudally (at the narrow apex), it articulates with the coccyx at the sacrococcygeal joint. The ventral or pelvic surface is concave from side to side and from above downward. The ventral rami of the first four sacral nerves and their associated vascular elements pass into the pelvis via four pairs of ventral sacral foramina. The transverse ridges between each pair of foramina represent the area where the intervertebral disc was once located. The promontory is the anterior enlargement of the upper portion of the body of S1. The pars lateralis (lateral mass) is the area lateral to the ventral foramina. During development, it is formed by the fusion of costal elements and transverse processes. The lateral surfaces of the upper two or three sacral vertebrae form an ear-shaped “auricular” surface that articulates with the ilium on each side. Ventrally, the lateral masses are marked by neural grooves that run laterally from each of the foramina. The large lateral masses of S1 are known as the alae. On the anterior aspect of each ala is a rounded bony groove formed by the lumbosacral trunk. The dorsal surface of the sacrum is convex in shape and has an irregular surface that includes median, intermediate, and lateral sacral crests representing the fused spinous, articular, and transverse processes, respectively. The shallow grooves between the median and intermediate crests are formed by fused laminae. The dorsal rami of the upper four sacral nerves and associated vascular structures pass through the four pairs of dorsal sacral foramina, located between the intermediate and lateral sacral crests. The dorsal sacral foramina are much smaller than the corresponding ventral sacral foramina. The laminae of the fifth (and on occasion the fourth) vertebra fail to fuse in the midline and form the sacral hiatus, which is the caudal opening of the sacral canal. The sacral cornu, a remnant of the inferior articular process, lies on each side of the sacral hiatus. Because the lumbosacral and sacroiliac joints transmit the entire weight of the body to the hip bones and lower limbs, these joints and their supporting ligaments must be very strong (Fig. 44-1). The strong dorsal ligamentous complex includes the interosseous ligaments and the dorsal sacroiliac ligaments. The very stout interosseous ligaments connect the sacral tuberosities to the overhanging bone of the iliac tuberosities and represent the single strongest ligaments binding the sacrum to the ilium. The dorsal sacroiliac ligaments are divided into deep (short) and superficial (long) parts. The deeper ligaments connect the sacral and ilial tuberosities and are composed of horizontally oriented fibers; the more superficial ligaments are oriented vertically and stretch from the posterior superior iliac spine to the tubercles of the lateral sacral crest. The caudal portions of the superficial dorsal sacroiliac ligaments blend with the sacrotuberous ligaments. The ventral ligamentous complex includes the ventral sacroiliac ligaments and the lumbosacral ligaments. The ventral sacroiliac ligament is a weak fibrous band that attaches to the base and lateral part of the sacrum and to the medial margin of the auricular surface of the ilium. The lumbosacral ligament is really a ventral band of the iliolumbar ligament. Three sets of accessory ligaments—the sacrospinous, sacrotuberous, and iliolumbar—also function to strengthen the pelvic girdle. The iliolumbar ligament originates on the transverse process of L5 and courses caudally and laterally to insert on the ilium. As discussed above, some fibers stretch ventrally to merge with the ventral sacroiliac ligament as the lumbosacral ligament. The sacrospinous ligament connects the lateral and anterolateral surfaces of the sacrum and coccyx with the ischial spine. This ligament divides the sciatic notch into greater and lesser sciatic foramina. Finally, the sacrotuberous ligament, an extensive structure, originates broadly from the posterior superior iliac spine and the dorsal and lateral aspects of the sacrum and coccyx to form a dense narrow fibrous band that inserts on the ischial tuberosity. In the erect position, the adult sacrum forms an angle of 70 degrees with respect to the vertebral column. Because the lumbosacral junction lies anterior to the sacroiliac joint, the axial load is transmitted to the ventral surface of the sacrum as a rotatory force that tilts the sacral promontory forward. The axis of this force is centered at S2. Several bony and ligamentous constraints check this rotatory tendency. The interosseous and dorsal sacroiliac ligaments resist forward rotation at the upper end of the sacrum, whereas the sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments resist the potential backward tilt of the sacral apex. Finally, bony constraints conferred by the interdigitating surfaces of the sacral alae and iliac bones in addition to the wedge-like configuration of the sacrum within the pelvis play an essential role in preventing sacral tipping. The clinical biomechanics of the sacrum is discussed in Chapter 41. The abdominal aorta bifurcates at the L4 level (Fig. 44-2). The small median or middle sacral artery arises from the posterior surface of the abdominal aorta close to the bifurcation and descends vertically along the pelvic surface of the sacrum. It gives rise to several small parietal branches that anastomose with the lateral sacral arteries and to small visceral branches that anastomose with the superior and middle rectal arteries. The median sacral artery ends in the coccygeal body, a small cellular and vascular mass located at the tip of the coccyx, the function of which is unclear. The aorta divides into the common iliac arteries that travel laterally and inferiorly to divide into the external and internal iliac arteries (Fig. 44-2). The internal iliac artery begins at approximately the level of the L5-S1 disc space, where it is crossed by the ureter. It is separated from the sacroiliac joint by the internal iliac vein and the lumbosacral trunk. The iliolumbar artery may arise form the common iliac artery, although it more commonly is the first branch of the internal iliac artery. This vessel runs superomedially, in close relation to the lumbosacral trunk, passing anterior to the sacroiliac joint and posterior to the psoas muscle. It later turns laterally and upward to divide in the region of the iliac fossa. FIGURE 44-1 Ligamentous anatomy of the lower lumbar spine, sacrum, and pelvis. (A) Ventral sacrum. (B) Dorsal sacrum. FIGURE 44-2 Relationship of the ventral surface of the sacrum to the major pelvic structures, arteries, veins, and neural structures. The lateral sacral artery is usually the second branch of the internal iliac, although it may originate from the superior gluteal. These vessels, usually a superior one and an inferior one, sometimes arise from a common trunk. They pass medially and descend downward anterior to the sacral ventral rami, giving branches that enter the ventral sacral foramina to supply the spinal meninges and the roots of the sacral nerves. Some branches may pass from the sacral canal through the dorsal foramina to supply the muscles and skin overlying the sacrum. The next two branches of the internal iliac artery are the superior and inferior gluteal arteries. The superior gluteal is a large artery that passes anteriorly across the lumbosacral trunk as the trunk passes over the ala. It then turns posteriorly between the lumbosacral trunk and the ventral ramus of the first sacral nerve to leave the pelvis through the superior part of the greater sciatic foramen, superior to the piriformis muscle (Fig. 44-2). The inferior gluteal artery passes posteriorly to pierce the sacral plexus more inferiorly (most often between S2 and S3) and exits the pelvis through the inferior part of the greater sciatic foramen, inferior to the piriformis muscle. The venous anatomy of the region generally parallels that of the arterial; however, it is more variable. It is important to note some important features. First, the vena cava lies to the right of the aorta at the bifurcation of the common iliac vessels. The right common iliac vein passes posterior to the artery and is therefore much shorter than the left common iliac vein. Second, the middle sacral vein, which is occasionally doubled, drains into the left common iliac vein rather than into the inferior vena cava. Finally, the iliolumbar veins drain into the common iliac veins rather than into the internal iliacs. Most tumors arising from the sacrum or presacral space, as well as some intraspinal masses, derive at least a part of their blood supply from the medial and lateral sacral arteries. Enlargement, displacement, or encasement of these vessels may be seen on angiography. The thecal sac ends blindly at the S2 level. The lower sacral and coccygeal nerves emerge from the sac, as well as the extradural portion of the filum terminale. The upper four roots exit the sacrum through the paired ventral and dorsal sacral foramina. The fifth sacral roots, the coccygeal roots, and the filum exit the sacrum caudally through the sacral hiatus. The filum terminale extends to its point of fusion with the periosteum of the first coccygeal segment. The sacral plexus is formed by the ventral rami of six roots: L4 through S3 and the upper part of S4. The lumbosacral trunk (the conjoined L4-L5 roots) forms a deep groove where it crosses the ala of the sacrum. It then descends obliquely over the sacroiliac joint and enters the pelvis deep to the parietal pelvic fascia. It crosses the superior gluteal vessels and joins the first sacral root. The sacral plexus is located on the anterior surface of the piriformis muscle, deep to the parietal (Waldeyer’s) fascia. Except for the nerves to the piriformis muscle, the perforating cutaneous nerves, and the nerves to the pelvic diaphragm, essentially all branches of the sacral plexus leave the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen (Fig. 44-2). The most important derivatives of the sacral plexus are the sciatic and pudendal nerves. The latter is unique in exiting the greater sciatic foramen only to reenter the lesser sciatic foramen by hooking around the sacrospinous ligament. It supplies the muscles of the perineum including the external anal sphincter and provides sensory information to the external genitalia. The coccygeal plexus is derived from the ventral rami of S4 and S5 as well as the coccygeal roots. It lies on the pelvic surface of the coccygeus muscle. It innervates the coccygeus muscle and provides some perianal sensation. Both the sympathetic and parasympathetic components of the autonomic nervous system have an intimate relationship with the sacrum. The sacral sympathetic trunk, continuous with the lumbar sympathetic trunk, descends against the ventral surface of the sacrum, converging in front of the coccyx to form the unpaired ganglion impar. Three to four sacral trunk ganglionic enlargements are found on each side of the midline, just medial to the ventral sacral foramina. No white rami communicantes are present in this region; however, the postsynaptic gray rami communicantes from each ganglion join the corresponding sacral or coccygeal nerves for distribution to sweat glands, blood vessels, and erector pylori muscles. As well, the sacral sympathetic trunks provide fine branches to the superior hypogastric plexus. The superior hypogastric plexus is the caudal continuation of the periaortic sympathetic plexus; it lies on the anterior surface of the fifth lumbar vertebra and upper sacrum in the retroperitoneal tissue. Fibers of the superior hypogastric plexus diverge into right and left hypogastric nerves opposite the first sacral vertebra. The term hypogastric nerve may be a misnomer because the structure is really a narrow plexus of fibers. The hypogastric nerves represent the principal sympathetic inputs to the inferior hypogastric plexus. The parasympathetic contributions to the pelvic plexi arise from the ventral S2 to S4 nerve roots. These preganglionic fibers form the pelvic splanchnic nerves (nervi erigentes). The parasympathetic system provides motor innervation to the detrusor muscle of the bladder and is primarily responsible for the vascular reflexes that sustain erectile function. The sympathetic system plays less of a role in normal voiding reflexes, but is important for male fertility by promoting timely transport of spermatozoa from the testes to the seminal vesicles and by coordinating reflexes responsible for ejaculation. In sacral resections, the clinical effects of lower motor neuron dysfunction (somatic sensory and motor deficits, urinary and fecal incontinence, sexual dysfunction) depend on the level and number of sacral nerve roots that are sacrificed. Several factors account for variations in the functional results reported after sacral resection, including anatomic variability among subjects, preoperative neurologic status, surgical technique and approach used, postoperative complications, follow-up time, and varied criteria used to evaluate the deficits. Nevertheless, an extensive review of the literature performed by Biagini and colleagues13 found some consistent correlation between the level of sacral resection and the extent of postoperative deficits. In patients with amputations distal to S3 (with removal of the last sacral roots and the coccygeal plexus), deficits are usually very limited, with preservation of sphincter function in the majority and some reduced perineal sensation. Sexual ability may be decreased. Transverse resections involving S2-S3 (including removal of one to all four roots of S2-S3) involve the highest variability in functional results. There is seldom any relevant motor deficit; however, many patients have saddle anesthesia and significant reduction in sphincter control. However, clinical observations by Stener and Gunterberg1 and others indicate that functional urinary and fecal continence is generally achievable if at least one S2 nerve root can be preserved. Section of the S1 roots or levels proximal to this result in clinically relevant motor deficits (walking with external support) associated with loss of sphincter control and sexual ability. Removal of sacral roots (S1-S5) on only one side, studied extensively by Stener and Gunterberg’s group,14 results in expected unilateral deficits in strength and sensitivity; however, sphincter control may be preserved or only partially compromised. No matter the level of resection, damage to the lumbosacral trunks or sciatic nerves may cause serious postoperative motor and sensory deficits. Likewise, damage to the parasympathetic and sympathetic plexi alone can result in problems with sexual ability and sphincter function. A detailed discussion of the evaluation of patients with sacral lesions, the indications for biopsy, the clinicopathologic characteristics of specific tumor types, and the various treatment options for different tumors is provided in Chapter 25. A review of some general principles is warranted here. The overall status of the patient, the anatomic extent of the tumor, and an appraisal of the likely biologic behavior of the tumor are major factors in determining the goals of surgery. Sacral tumors are classified on the basis of their biologic behavior as benign tumors, low-grade locally aggressive tumors, and high-grade malignancies. Benign encapsulated tumors may be treated with lesional resection. Low-grade malignancies, such as giant cell tumor or chordoma, require an en bloc resection including a circumferential margin of uninvolved tissue to effect cure.9,15 The surgical treatment goals are similar for localized high-grade malignancies such as osteosarcoma and even some locally advanced pelvic cancers. Simple intralesional curettage or cryosurgery for benign and low-grade tumors is generally discouraged due to unacceptably high local recurrence rates.16 All patients referred for the resection of sacral tumors should be assessed completely for evidence of local and systemic spread. This may require computed tomography (CT) of the chest and abdomen as well as a bone scan. Cystoscopy may be useful in some cases. Cancers of the rectum and pelvic organs must be thoroughly staged before any consideration for surgical resection. Repeated radiographic and clinical staging studies may be indicated for patients with primary sacral tumors initially thought to be inoperable due to advanced local spread of disease, because patients may become operative candidates following treatment with neoadjuvant chemotherapy or other therapy. The need for careful patient selection can never be understated. It is important to discuss the operation at length with the patient prior to surgery. Sacral resections are associated with a high risk of morbidity and may involve inherent functional consequences with regard to bladder, bowel, and sexual functions. Special attention must be given to the preparation of the bowel before any sacral procedures. The lower extent of posterior sacral incisions is located very near the anus, and thus wound contamination is of great concern. With anterior approaches, there is the risk of inadvertently entering the bowel during the procedure. A low residue diet is advisable for several days prior to hospitalization. Preoperatively, mechanical cleaning of the bowel is performed by having the patient drink GoLytely. In addition, we generally use prophylactic antibiotics, such as second-generation cephalosporins, both preoperatively and in the immediate postoperative period. Procedures involving sacral resection may be complicated by profuse blood loss. Preoperative angiographic embolization is a worthwhile consideration for many lesions, notably for giant cell tumor.17 Good vascular access including large-bore intravenous catheters is necessary to administer large volumes of fluids and blood. Central venous pressure monitoring is almost always needed; a Swan-Ganz catheter may be warranted in selected patients. We have generally avoided use of the cell saver because of the potential for tumor dissemination. Exposure of the sacrum is complicated by many factors, including its location deep within the pelvis, its intimate relationships with neurovascular structures and pelvic organs, its lateral iliac articulations, and the dorsal overhang of the iliac crests.18 In addition, due to the capacity of the sacral canal and pelvis to accommodate regional expansion, tumors of the sacral region may attain enormous dimensions by the time of clinical detection. Because of tumor size and the constraints posed by regional anatomy, the standard unidirectional approaches (anterior, posterior, perineal, lateral) are frequently combined to achieve an adequate exposure. Combined approaches may be performed simultaneously, performed consecutively under the same anesthetic, or staged. The major advantages of the posterior transsacral approach are its familiarity and technical ease, wide access to the intraspinal and intradural compartments, and clear identification of neural tissue. It is the procedure of choice for the resection of intraspinal tumors and cysts with little or no presacral extension. The patient is usually placed in the prone position, although a lateral decubitus position allows combination with other approaches. Prone positioning facilitates proper radiographic placement of screws with fluoroscopic monitoring and the use of the surgical microscope. The latter is particularly important in the resection of intradural tumors such as schwannomas and ependymomas, which need to be clearly distinguished from surrounding neural tissue. With prone positioning, it is important that the abdomen be free of pressure so that bleeding is minimized. Due to the proximity of the incision to the anal orifice, extra care in skin preparation and the use of plastic adhesive barrier drapes is advisable. The potential for wound contamination may be further reduced by temporarily closing the anus with a purse-string suture. The principles of this dorsal approach are familiar to most neurosurgeons. The incision may be midline or transverse, depending on the preference of the surgeon and exposure requirements. During the subperiosteal dissection, blood vessels are frequently encountered penetrating the dorsal sacral foramina. Sacrifice of the dorsal rami is unavoidable, but does not cause serious functional sequelae. As long as the sacroiliac joints are left intact laterally, disruption of the dorsal sacroiliac ligaments to achieve a wider exposure of the canal should not lead to mechanical instability. Laminectomies are performed using standard techniques. Limited access to the caudal presacral space may be achieved by resection of the coccyx and division of the anococcygeal muscles. Following tumor resection, any dural defects should be closed in a watertight fashion, and lumbar spinal drainage is advisable. The transperineal approach allows easy access to the caudal presacral space with minimal morbidity. It can be used alone for cyst drainage or tumor biopsy but is most frequently combined with a posterior midline exposure for the en bloc resection (i.e., low sacral resection) of lesions at or below the S3 level. The transperineal approach is not recommended for higher sacral amputations, because it is difficult to accurately dissect the soft tissues of the upper sacrum, thereby increasing the risk of major vascular injury, damage to the rectum and lumbosacral trunk, and violation of the tumor capsule. The patient is placed in the Kraske position (flexed prone), and a midline incision is made extending rostrally from the coccygeal region. Access to the presacral space is afforded by division of the anococcygeal ligament (Fig. 44-3). The caudal sacrum may be osteotomized after transection of several soft tissue attachments, including the gluteus maximus, the sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments, and the piriformis muscle. The transperineal approach is discussed in detail later (see Low Sacral Resection). Ventral access to the sacrum may be obtained via a transabdominal or retroperitoneal route. The wide exposure of the middle and upper sacrum afforded by either approach facilitates dissection of the rectum and other pelvic contents from the tumor surface while providing early access to the vascular supply of the tumor. An anterior sacral approach alone may be indicated for palliative debulking of malignant tumors with significant presacral extension, for resection of predominantly presacral lesions, or for intralesional or marginal resection of anterior sacral body tumors with or without presacral extension. However, an anterior approach is most often combined with a staged or simultaneous posterior approach for sacral amputations above the level of S3. In this circumstance, the anterior approach is used to gain vascular control, dissect the rectum and other pelvic contents from the tumor, and complete the anterior osteotomy; the posterior approach is used to dissect and transect the dural contents and to complete the sacral amputation. Anterior approaches are not appropriate for the exposure of intradural lesions or tumors with significant intraspinal involvement.

Surgical Approaches for the Resection of Sacral Tumors

Anatomical Considerations

Anatomical Considerations

Bony and Ligamentous Anatomy

Vascular Anatomy

Neuroanatomy

Functional Considerations

Functional Considerations

Principles of Surgical Treatment

Principles of Surgical Treatment

Preoperative Management

Preoperative Management

Surgical Approaches

Surgical Approaches

Posterior Transsacral Approach

Transperineal Approach

Anterior Approaches

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree