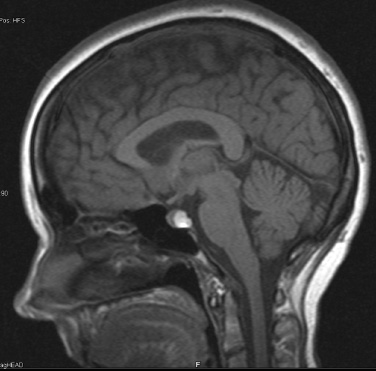

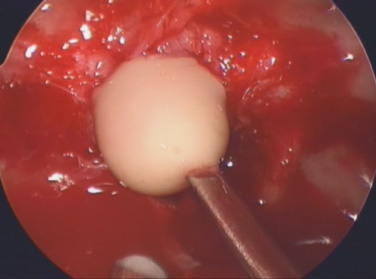

10 Surgical Treatment of Rathke Cleft Cysts Luschka provided the earliest description of a Rathke cleft cyst (RCC) in 1860.1 He described RCCs as “an epithelial area in the capsule of the human hypophysis resembling oral mucosa.” Over the next century, they were alternately described as pituitary cysts, mucoid epithelial cysts, or colloid cysts until Frazier and Alpers finally identified them as a lesion of the Rathke cleft in 1934.2 Just as the nomenclature varied, so did the theories of origin. RCCs were variously believed to have originated from neuroepithelium, endoderm, and metaplastic anterior pituitary cells3–9 before they were finally identified as being derived from embryologic remnants of the Rathke pouch.10–16 It is now widely accepted that the Rathke pouch arises from a dorsal outpouching of the stomodeum that comes into contact with the downward outpouching of the neuroepithelium from the diencephalon. The pharyngohypophyseal trunk separates from the oral epithelium and is eventually completely severed by the sphenoid bone. The resulting pouch is lined by epithelial cells of ectodermal origin. The anterior and posterior walls become the pars distalis and pars intermedia, respectively, and the residual lumen involutes and normally regresses.2,16 When it abnormally expands, it is known as an RCC. On histopathologic specimen, the cyst wall is lined with a well-differentiated, ciliated columnar epithelium, which may contain goblet or ciliated cells. The cyst contents are primarily mucinoid, but appearances vary between lesions from nearly clear fluid to seemingly purulent material comprising necrotic debris.17 Leakage of the cyst contents may result in inflammation that transforms the columnar epithelium into a stratified squamous epithelium more suggestive of a craniopharyngioma.18,19 RCCs account for fewer than 1% of primary brain tumors.20–22 The majority of RCCs are probably never symptomatic or diagnosed because there is a population incidence of 3 to 22% on autopsy studies.1,9,15,21,23–27 Clinical series exhibit a nearly 2:1 female predominance, which is generally attributed to the fact that pituitary dysfunction is more readily apparent in females (ie, amenorrhea, galactorrhea).15,23,24,28–31 This female predominance is not evident in autopsy series.23 Symptomatic RCCs may be diagnosed at any age.15,24,30,32,33 Progressive enlargement of the cyst may result in symptoms of anterior lobe dysfunction, posterior lobe dysfunction, stalk compression/distortion, visual phenomena, and headaches (Table 10.1).15 The duration of symptoms may range from a few days to years, with the more acute presentations likely secondary to intracystic hemorrhage or leakage of cyst contents resulting in acute inflammation.18,29,34,35 Headaches are generally the primary complaint in patients of any age, occurring in 70 to 85% of patients; they are most frequently frontal in location, with an average duration of 12 months before clinical diagnosis.34–37 In their metaanalysis, Voelker et al found that children are more likely to present with hypopituitarism, including growth retardation and delay in sexual maturation, which take place over months to years.15 Alternatively, adults usually present with symptoms of pituitary stalk, anterior pituitary, or posterior pituitary insufficiency. Men may develop decreased libido, decreased body hair, and fatigue. Premenopausal women may have amenorrhea (63%), galactorrhea (63%), or diabetes insipidus.15,24,32,38,39 Conversely, postmenopausal women present with symptoms of panhypopituitarism, constitutional symptoms, and/or mental status changes.15 Visual phenomena, including bitemporal hemianopsia, are also common in adults with symptoms of long-standing duration.16 Hemianopsias or superior quadrantanopsias have been reported with RCCs as well. Up to two-thirds of patients with RCC harbor endocrinopathies secondary to hypothalamic, adenohypophyseal, neurohypophyseal, and infundibular compression.29,35 RCCs are associated with hyperprolactinemia secondary to pituitary stalk compression in as many as 18% of patients.32,38,39 This is followed in frequency by hypocortisolism, hypothyroidism, hypogonadism, and growth hormone deficiency. Hypopituitarism with more than one axis affected occurs in 10 to 15% of patients.34 A thorough evaluation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–end-organ axis must be performed before surgery because hypocortisolemia and hypothyroidism can be associated with increased perioperative morbidity and mortality16 (Table 10.2). Stress-dose hydrocortisone should be given to all patients with adrenal insufficiency at the time of surgery. Urine and serum electrolytes and osmolarity should be analyzed preoperatively and postoperatively to assess for diabetes insipidus. The hypothalamic–pituitary–end-organ axis should be checked serially in follow-up to ensure integrity. Up to one-third of patients with RCCs present with visual dysfunction.29 Most commonly, this manifests as diminished acuity or a visual field deficit. All patients should undergo formal funduscopic, tangent screen, and perimetric testing to establish a visual baseline and assess for clinical signs of cyst growth and compression (Table 10.2). The earliest reports of RCCs included skull radiographs demonstrating asymmetry of the sellar floor secondary to sellar erosion, with or without abnormal calcifications.11,40,41 The advent of computed tomography (CT) more accurately depicted RCCs as well-circumscribed, hypodense to isodense cysts with rare calcification in the sella/suprasellar region.42 Variances in densities within the cyst are likely due to variable concentrations of cholesterol crystals or mucinoid contents.43–45 One-third to one-half of RCCs are found within the sella.18,29,34,35 Only a small number are exclusively suprasellar.46–49 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan with fine cuts through the pituitary region should be performed to help differentiate an RCC from other similarly appearing lesions, such as epithelial cyst, dermoid cyst, epidermoid cyst, and craniopharyngioma.50,51 An RCC appears as a characteristic hypointense to isointense homogeneous cyst on T1-weighted MRI that fails to enhance with contrast in the majority of patients34,44 (Figs. 10.1 and 10.2). However, up to 25% of patients may show some contrast enhancement owing to cyst fluid extravasation and inflammatory changes in the capsule.34 Hyperintense cyst fluid on T1-weighted (Fig. 10.3) and T2-weighted MRI often has a high protein content, and a fluid level may be present.31,46,50,52 Patients with intracystic hemorrhage have cysts that are often hyperintense on T1 and hypointense on T2.53 Recent studies have shown that RCCs are hypointense to brain parenchyma on diffusion-weighted imaging and have a higher apparent diffusion coefficient than do craniopharyngiomas and pituitary adenomas.54 Most lesions are centrally located within the pituitary gland and are less than 1.5 cm in diameter.31,55 Larger lesions may appear dumbbell-shaped as they extend into the suprasellar region.15,42 If the cyst continues to expand and obstructs the foramina of Monro and the third ventricle, hydrocephalus may be present.16 Fig. 10.1 Hypointense Rathke cleft cyst on T1-weighted MRI. Fig. 10.2 Isointense Rathke cleft cyst on T1-weighted MRI. Fig. 10.3 Hyperintense Rathke cleft cyst on T1-weighted MRI. In the modern treatment era, gadolinium-enhanced MRI should be performed with focused pituitary sequencing in three planes (Table 10.2). This aids in diagnosis and operative planning, allowing the surgeon to understand the relationship between the cyst and the optic nerves, chiasm, pituitary, infundibulum, hypothalamus, carotid arteries, and cavernous sinuses.16,42,46 CT may also be of benefit for assessing the degree of calcification for diagnostic purposes, as well as planning transsphenoidal approaches. Asymptomatic patients with an incidentally discovered cystic lesion in the sellar/suprasellar region should undergo the appropriate endocrine, ophthalmologic, and imaging evaluation, but treatment is rarely indicated. For patients who present with headaches as their sole complaint, a full headache evaluation and medical treatment should be employed initially. When a patient has a large but relatively asymptomatic cyst, serial imaging may be used to assess for further cyst expansion or compression of the optic chiasm. When a patient becomes symptomatic as a result of endocrinopathies or visual deficits, or if a patient has medically refractory headaches, surgical intervention is warranted. In 1934, Frazier and Alpers2 performed the first successful craniotomy for resection of “tumor of the Rathke pouch.” Their patient was “gainfully employed and asymptomatic” during the 3-year follow-up period. As such, RCCs were primarily resected via craniotomy until the 1970s, when Hardy et al recommended the microsurgical transsphenoidal approach.56,57 The incidence of aseptic meningitis secondary to rupture of cyst contents into the subarachnoid space during a craniotomy has declined with use of the transsphenoidal approach.27,58 With more modern neuroimaging techniques to assist in operative planning, newer techniques such as the direct endonasal and endoscopic transsphenoidal approaches have also proved to be safe and effective for fenestration and/or resection of RCCs.59 Thus, the craniotomy is now reserved for lesions with suprasellar or parasellar components that would be difficult to access via the transsphenoidal route.30,60 The surgical approaches are detailed in Chapters 11 (“Transsphenoidal Approaches to the Sellar and Parasellar Area”) and 12 (“Transcranial Approaches to the Sellar and Parasellar Area”). There are two main surgical treatment strategies for symptomatic RCCs: simple fenestration and aggressive cyst wall resection.16 The surgical decision making should take into account the patient’s age, sex, desire for fertility, and comorbid medical conditions, in addition to the severity of symptoms.61 The most common strategy for the treatment of RCCs includes a fenestration of the cyst, evacuation of cyst contents, and biopsy of the cyst wall11,15,23,24,29,30,43,62 (Fig. 10.4). Generally, there is little or no attempt to remove the cyst wall from the surrounding gland, and when possible, the sellar floor is not reconstructed, to allow the cyst to continue to drain into the sphenoid sinus.29 This strategy allows relief of the symptomatology with little pituitary dysfunction but has previously been associated with a higher recurrence rate in the literature.34–37,63 A more aggressive strategy involves complete cyst wall resection. This technique has traditionally been associated with a lower recurrence rate;16,61,64 however, it is associated with increased rates of postoperative cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks and pituitary dysfunction, including diabetes insipidus.35 Fig. 10.4 Intraoperative endoscopic transsphenoidal view of a Rathke cleft cyst. The transsphenoidal microsurgical approach has traditionally been the mainstay of the transsphenoidal surgical treatment of primarily intrasellar RCCs.16 This may be performed via either a sublabial or an endonasal approach. Although the benefits include a three-dimensional view, the surgeon may be limited by a fixed view and smaller field. This approach continues to be favored for children, whose small nares may not allow passage of transsphenoidal instruments. The endoscopic transsphenoidal technique is used for the majority of RCC patients at our institution. In contrast to a microsurgical technique, the endoscope allows a wider field, angled viewpoints, and closer inspection.22,63,65–67 The approach includes a two-nostril technique with wide exposure of the sphenoid sinus to maximize the surgeon’s working space. The sella turcica is exposed widely with Kerrison rongeurs. For cysts with suprasellar extension and a prefixed chiasm, further removal of the tuberculum and a portion of the planum sphenoidale may be warranted and allows an extended transsphenoidal approach (although the increased risk for a postoperative CSF leak must be kept in mind).68 When this more extended approach is to be performed and a CSF leak is anticipated preoperatively, a pedicled nasoseptal mucosal flap may be harvested at the beginning of the case to be used for the reconstruction.69 Otherwise, attempts are made to preserve the nasoseptal artery on which this flap is based in the event an unexpected CSF leak is encountered and a “rescue” flap reconstruction may be necessary.70 The ability to switch between angled endoscopes allows the visual confirmation of complete removal of the cyst contents and provides a view of the internal cyst cavity. Following cyst collapse, in the absence of a CSF leak, we do not repair the sellar floor so as to allow continued drainage.29 The surgical treatment of Rathke cleft cysts is associated with dramatic relief of headaches, visual dysfunction, and symptoms of hyperprolactinemia, including amenorrhea and galactorrhea16 (Table 10.3). There is much less anticipated relief of the symptoms of hypopituitarism and diabetes insipidus after surgery. Headaches are present in 44 to 81% of patients preoperatively, and modern studies show a 60 to 100% resolution rate.15,34–36 Patients with persistent postoperative headaches tended to have chronic headaches preoperatively, whereas patients who presented with severe headache (possibly due to leakage of cystic contents and inflammation) were more likely to experience resolution.35 Visual loss is present in 11 to 67% of patients preoperatively on ophthalmologic examination, and as many as 92% of these patients have complete return of vision postoperatively.71 Modern series have not reported new cases of visual deficits postoperatively. Endocrinopathies occur in 30 to 60% of patients preoperatively. A decrease in anterior pituitary dysfunction occurs in 15 to 70% of patients postoperatively, especially those with amenorrhea or galactorrhea.18,23,34–38,72,73 Endocrine outcomes were best summarized by el-Mahady and Powell when they stated that patients with the poorest preoperative status have the poorest recovery rates.29 As the RCC walls are intrinsically attached to the surrounding pituitary gland and stalk, dissection and resection of the cyst wall is associated with an increased incidence of postoperative diabetes insipidus and secondary hypopituitarism when compared with simple fenestration alone. Postoperative anterior pituitary dysfunction occurs in as many as 40 to 60% of patients,35,63 and permanent postoperative diabetes insipidus occurs in as many as 40 to 50%.35,37 It has been theorized that the high rate of diabetes insipidus in patients with RCCs is a result of inflammation and extension into the surrounding pituitary gland.17 Only rarely does preoperative diabetes insipidus resolve after surgery.16 Fenestration of the cyst is associated with a recurrence rate of ~10%34–36,74 (Table 10.4). Other factors associated with relapse include cyst wall enhancement on MRI34,50,51,56 and histopathology. Multiple authors have documented that squamous metaplasia on histopathology is associated with higher rates of relapse.17,34 This suggests that even in cases in which the goal is fenestration alone, it is helpful to remove a small portion of the cyst wall for pathology review. Patients with squamous metaplasia should be followed more closely postoperatively because they may have a more aggressive lesion that can become reencapsulated and reaccumulate cystic fluid.16 Recurrence rates further vary based on the length of follow-up and the imaging schedule employed in follow-up. Over all, recurrence rates appear to be less than 20%, with Shin et al reporting the longest recurrence-free survival of 85% at 5 years and a few late recurrences resulting in a recurrence-free survival of 81% at 20 years.31 Postoperative complications of the surgical treatment of RCCs are related to the surgical approach and strategy. CSF rhinorrhea occurs in fewer than 3% of patients treated via a transsphenoidal approach and is almost exclusively a result of cyst wall dissection/resection.30,35,37 It is treated surgically by repairing the sellar defect with abdominal fat, a bone, or a synthetic buttress to the floor of the sella and application of a glue or bonding agent. Conservative treatment measures include lumbar drainage.16 Meningitis is a rare consequence of RCC resections. Aseptic meningitis may be associated with leakage of the cyst contents into the subarachnoid16 and can be managed with corticosteroids provided that meningitis related to infection is not present. CSF cultures should be obtained to rule out bacterial meningitis. Bacterial or fungal meningitis may result from a CSF leak related to a transsphenoidal approach. Treatment includes obtaining CSF cultures to isolate the offending organism, broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics, and repair of any obvious CSF leak.29,30,35–37 All patients should be followed closely by a multidisciplinary team consisting of a neurosurgeon, endocrinologist, and neuro-ophthalmologist at 8 to 12 weeks postoperatively and annually thereafter. Postoperative imaging should be obtained to establish a baseline after surgery and should be performed annually for the first several years before the time interval is increased. Ophthalmologic evaluations should be performed annually for patients who presented with visual deficits. Repeated recurrence of an RCC has been successfully treated with gamma knife radiosurgery. RCCs pose a challenging problem for the neurosurgeon whether they are managed surgically or conservatively. Transsphenoidal surgery has been established as the standard operative approach. The operative strategy, including the degree of surgical resection of the RCC, should be patient-specific, with a full discussion of the risks and benefits. Advancing technology, such as the three-dimensional endoscope, may continue to improve operative outcomes. Close follow-up with a multidisciplinary team is essential to recognize recurrences and the need for further treatment.

Prevalence

Prevalence

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Endocrinologic Evaluation

Endocrinologic Evaluation

Ophthalmologic Assessment

Ophthalmologic Assessment

Diagnostic Imaging

Diagnostic Imaging

Indications for Surgery

Indications for Surgery

Operative Approaches

Operative Approaches

Surgical Techniques

Surgical Techniques

Microscopic Transsphenoidal

Endoscopic Transsphenoidal

Outcomes

Outcomes

Clinical Outcomes

Relapse

Complications

Complications

Follow-up

Follow-up

Conclusion

Conclusion

References

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree