Fig. 3.1

Postural abnormality of a patient with Parkinson’s disease. The elbows, hips, and knees are flexed; the trunk is bent forward; and the arms are held in front of the body (Reproduced from the sketch of Sir William Richard Gowers)

Fig. 3.2

Pisa syndrome. The sustained lateral bending of the trunk is evident (a) A 82 year-old woman manifesting Pisa syndrome and camptocormia. (b) A 73 year-old woman with Pisa syndrome and a dropped head.

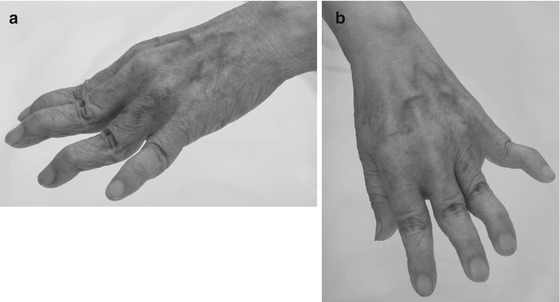

Fig. 3.3

Striatal hand. Note the characteristic deformity of the hands with metacarpophalangeal flexion, proximal interphalangeal extension, and distal interphalangeal flexion, resembling the swan-neck deformities in arthritic disorders (a) viewed sidewise (b) seen from above

3.1.2.6 Freezing

The freezing phenomenon is sudden, transient inability to perform movements. Freezing occurs in opening the eyelid (eyelid opening apraxia), speaking, and writing. However, if walking is affected, it is troublesome for the patient. The feet seem glued to the floor, and starting to walk delays (start hesitation). After several seconds, the feet suddenly become unstuck and the patient can start walking with shuffling steps. However, freezing reappears when the patient attempts to turn or approaches a destination (destination hesitation), such as a chair in which to sit. Gait freezing is frequently induced when the patient passes through a narrow doorway, especially under hastened situation, such as entering train doors or elevator doors those may close. Interestingly, entering escalators or stairs causes less trouble because each step acts as visual clues. Freezing accompanied with loss of postural reflexes is a great risk of falling and hip fractures.

3.1.3 Nonmotor Symptoms

3.1.3.1 Autonomic Dysfunction

In PD patients, various autonomic disturbances develop.

Constipation is a representative premotor symptom and a major complaint for many patients. Insufficient movements and drinking little water may contribute its exacerbation. Severe constipation could result in the enlargement of colon and lead to obstructive ileus requiring a surgical procedure.

Bladder dysfunction is a rather later symptom. Difficulty in emptying the urinary bladder leads to frequent urination. Nocturnal pollakisuria not only disturbs the patient’s sleep, but also increases the risk of fall.

Sexual dysfunction appeared in PD patients includes decreases in libido, sexual intercourse, and orgasm. In men, difficulty in maintaining erection and delayed ejaculation also occur. Dopamine deficiency is presumably related to these problems. Recently, hypersexuality induced by levodopa treatment has drawn attention as a troublesome aspect of impulse control disorder.

Orthostatic hypotension usually becomes apparent in the advanced stage. The patient is aware of the symptoms of faintness, dizziness, or lightheadedness on standing or walking. Orthostatic hypotension is likely aggravated by antiparkinsonian medications. Another disturbance of blood pressure control is postprandial hypotension. Symptoms tend to be more severe after eating a large meal or a meal that includes a lot of carbohydrates.

Excessive sweating is a common symptom of PD. It may manifest on a part of the body, but can be generalized. In patients with wearing off phenomenon, it tends to be seen at off period. The excessive sweating appears to be a response to normal stimuli in an exaggerated manner.

Seborrhea is excessive discharge of sebum, the oily, waxy substance secreted from the sebaceous gland of the skin. A subsequent infection and inflammation causes seborrheic dermatitis. The skin of the face at the sides of the nose, the forehead, and the scalp is particularly affected.

3.1.3.2 Sensory Symptoms

Hyposmia, a manifestation of olfactory dysfunction, is one of the most important premotor symptoms. It may precede the onset of motor symptom by many years. Furthermore, hyposmia in PD is more severe than that found in patients with other parkinsonian syndromes such as progressive supranuclear palsy, multiple system atrophy, and corticobasal degeneration. Therefore, the recognition of the olfactory deficit in parkinsonian patients helps making a clinical diagnosis of PD. In addition, a recent report suggests that olfactory dysfunction is a prodromal symptom of dementia associated with PD (Baba et al. 2012).

Painful symptoms in PD are quite commonly present, although neurological examinations reveal no objective sensory impairment. Sensory symptoms include numbness, tingling, and burning, those occur in the region of motor involvement. To note, dull pain may be present even before appearance of rigidity or akinesia in the same limb.

Painful symptoms are classified into five categories: (1) musculoskeletal pain, (2) radicular or neuropathic pain, (3) dystonia-related pain, (4) central pain, and (5) akathitic discomfort (Ford and Pfeiffer 2005). Musculoskeletal pain is related to rigidity and akinesia, aggravated at off period, and relieved by levodopa. The postural deformities in PD may predispose to the development of radiculopathy. Dystonia appears not only at off period as the deficit of dopamine, but also at on period as a medication-induced symptom. Central pain is originated from the brain and is resistant to treatment. Akathisia is characterized by subjective inner restlessness. The patient is unable to sit still and bothered especially during off period. Similarly, restless legs syndrome (RLS) is characterized by uncomfortable sensation of legs that disappears with movement. Akathisia is present most of the day, while RLS aggravates during evening and night. However, these two conditions are sometimes difficult to distinguish, because both may respond to dopamine replacement therapy.

3.1.3.3 Sleep and Awakening Disturbances

Sleep problems encompass RBD, RLS, insomnia, and sleep apnea. Awakening problems are encountered with dopaminergic therapy including excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) and sleep attacks.

RBD is a pathological state of REM in which the normal atonia of REM sleep is lost, enabling motor activity during REM sleep, leading to respond to dreams. Dream content during RBD episodes is often threatened, chased, or attacked ones. Therefore, the patients yell, clap, punch, kick, sit, stand, fall out of bed, and run. These violent behaviors may injure both the patients and bed partners during RBD episodes. The patient may not only suffer from lacerations, ecchymoses, and bone fractures, but also pommel and choke the bed partner. The patient is unable to remember the behavior when awakens in the morning.

The patients with RLS feel dysesthesias in the legs at rest, which is aggravated in the evening and at nighttime. The dysesthesias are expressed as tingling, creeping, crawling, burning, itching, aching, or other sensations. It is relieved by moving the legs or walking, thus the patient feels irresistible urge to move the legs. Many patients with RLS also experience periodic limb movements in sleep (PLMS). RLS resembles akathisia, however, RLS can cause sleep fragmentation and EDS.

EDS is defined as an increased propensity to fall asleep at daytime. The causes of EDS in PD patients include antiparkinsonian medications, RBD, PLMS, nightmares, hallucinations, dyskinesias, and symptoms of PD such as tremor, rigidity, nocturia, central pain, sweating, etc.

Sleep attacks is a sudden episode of sleep without warning. Frucht et al. first described PD patients taking nonergot dopamine agonist who had sudden onset of sleep during driving (Frucht et al. 1999). Subsequently, many PD cases with sleep attacks have been reported. The risk factors of sleep attacks include duration of illness, medication of dopamine agonists or levodopa, and EDS. However, it is difficult to precisely predict who is at risk of sleep attacks while driving, and there are no guidelines to determine who is safe to drive.

3.1.3.4 Psychological Disturbance

The most common psychiatric symptom that affects PD patients is depression. It is important to discriminate a depressive state as a manifestation of PD from major depression. In PD, a guilty conscience or attempting suicide is not a predominant symptom, instead apathy and anhedonia could be dominated. Apathy is a state of loss of emotions such as concern, excitement, motivation, and passion. Anhedonia is defined as the inability to experience pleasure from activities usually found enjoyable, such as hobbies, music, sexual activities, or social interactions. The patient becomes dependent, indecisive, passive, and lacks motivations. It is known in PD patients that apathy or anhedonia can manifest independently from depression.

Anxiety is another psychological problem that is frequently seen in PD patients. Anxiety disorder includes panic attack or obsessive–compulsive behavior, manifesting at off state. It can precede motor manifestations.

Fatigue is also common in PD. It may present as one of symptoms of depression, but recently it can manifest by itself in parkinsonian patients. Mental fatigue is a subjective tiredness and physical fatigue indicates gradual reduction of amplitude or velocity of motion, detectable in finger tapping or rapid alternating movement procedures. Mental fatigue and physical fatigue are known to occur independently in PD.

Impulse control disorder is a behavioral adverse effect associated with dopamine replacement therapy (Voon et al. 2009). Pathological gambling and shopping, compulsive eating, hypersexuality, and compulsive medication use are its representative symptoms. The patient also suffers from punding (abnormal repetitive nongoal oriented behaviors). These symptoms are collectively called as dopamine dysregulation syndrome.

3.1.3.5 Cognitive Decline

Dementia is generally not an early feature of PD. In early stage, the patient responds to questions slowly, but when given enough time, correct answers can be obtained (bradyphrenia), indicating that memory function itself is not impaired. However, as the disease progresses, higher cognitive dysfunctions become prominent. Dementia in PD is clinically associated with older age and severe motor symptoms. Most of PD patients with dementia have Lewy bodies in cortical neurons (dementia with Lewy bodies: DLB), and the others may develop concurrent Alzheimer pathology, multiple infarctions, or other neurodegenerative disorders. Although it is often difficult to distinguish these disorders in each patient, early features of DLB are executive dysfunction, impaired verbal fluency, and visuospatial disturbances, while memory impairment comes late. The other representative symptoms which characterize DLB include fluctuating attention and concentration, recurrent well-formed visual hallucinations, and severe neuroleptic sensitivity. Mckeith et al. have proposed in the report of the consortium on DLB international workshop that fluctuation in cognitive function, persistent well-formed visual hallucinations, and spontaneous motor features of parkinsonism are core features with diagnostic significance in discriminating DLB from AD and other dementias (McKeith et al. 1996).

3.1.4 Motor Complications

3.1.4.1 Fluctuations

At an early stage of PD, the beneficial effect of levodopa is sustained and motor symptoms are stably controlled throughout the day. This effect is attributed both to a prolonged storage of levodopa-derived dopamine within residual dopaminergic nerve terminals and to a prolonged postsynaptic effect on dopamine receptors. However, with chronic levodopa therapy motor fluctuations gradually appear. Wearing off phenomenon or end-of-dose deterioration is, by definition, a return of parkisonian symptoms in less than 4 h after the last intake of medication. Beneficial time of levodopa (on period) progressively shortens, and the motor dysfunction in the deteriorated time (off period) becomes more profound. Another subset of motor fluctuations is on–off phenomenon in that the changes between on and off come abrupt and are not related to the timing of the levodopa dosing. One of the causes of these fluctuations is further reduced dopamine storage in the progressively lost residual dopaminergic nerve terminals. However, the failure of elimination of fluctuations by direct-acting dopamine agonists provokes the possibility that the sensitivity of dopamine receptors is modulated. Large width between the peaks and the bottoms of the striatal dopamine concentrations due to intermittent levodopa administration is hypothesized as a cause of the altered sensitivity of dopamine receptors.

Fluctuations are known to appear not only in motor functions but also in nonmotor symptoms, such as mood, anxiety, and pain. These behavioral and sensory offs can occur in the absence of motor offs. This nonmotor offs may underlie the dopamine dysregulation syndrome.

3.1.4.2 Dyskinesias

Chronic levodopa therapy and altered sensitivity of dopamine receptors affect the dyskinetic effects. Dyskinesias usually take forms of chorea, ballism, dystonia, or their combination. Mild dyskinesias are not troublesome and even unnoticeable. However, severe forms can be disabling.

Dyskinesias are categorized into several forms according to the timing of levodopa intake. The most common is peak-dose dyskinesias, those appear at the peak of levodopa concentration when parkinsonian symptoms are well controlled. Diphasic dyskinesias appear at the beginning and end of the dosing when levodopa concentrations change acutely. In this case the involuntary movements affect mainly the legs.

Off dystonias appear during off periods and is often painful. The patients may experience early morning dystonia, which affects the feet for several minutes. This is ameliorated by levodopa administration.

3.2 Dystonia

3.2.1 General Consideration

Dystonia is defined as a syndrome of sustained muscle contractions, frequently causing twisting and repetitive movements or abnormal postures. To stress its twisting quality of movements and posture, the term torsion is sometimes placed in front of the word dystonia, as torsion dystonia. The voluntary muscles in the face, trunk, and limbs can be affected by dystonia. When rhythmic, repetitive muscle spasms of the limbs occur in patients with torsion dystonia, the term dystonic tremor is applied.

Dystonia can be elicited by a specific action. This condition is called as task–specific dystonia, including writer’s cramp and occupational cramp. Dystonia is induced or exacerbated by emotional stresses, fatigue, and also by voluntary movements in parts of the body not affected by dystonia. Exacerbation of truncal dystonia during talking is an example. With progression, dystonic movements can develop while at rest, and finally bizarre dystonic postures become sustained.

A characteristic feature of dystonic movements is that they can be reduced by tactile sensory tricks. The patients with cervical dystonia (spasmodic torticollis) can diminish their abnormal muscle contractions by placing a hand on the side of the face. Lying down on the floor can reduce truncal dystonia. The oral dystonia can be suppressed in touching the lips or placing something in the mouth. Dystonia is also relieved with relaxation and sleep.

Some patients with dystonia, especially of young age, may experience a sudden exacerbation of the severity of dystonia, called status dystonicus. These patients should be intensely treated by using sedatives such as propofol, because the induced myoglobinuria may cause renal failure.

3.2.2 Classification of Dystonia

Dystonia can be classified by age at onset, by distribution of dystonia, and by etiology (Fahn and Bressman 2010).

Age at onset is in childhood (0–12 years), in adolescence (13–20 years), or in adult (later than 20 years). Patients with the younger age at onset tend to progress severe and generalized symptoms, whereas cases with the older age at onset likely remain focal dystonia. Thus, age at onset is the factor most related to prognosis of dystonia.

Distribution of dystonia may be focal, segmental, multifocal, generalized, or hemidystonia. Focal dystonias are those when only a single body part is affected. The most common focal dystonia is spasmodic torticollis, followed by blepharospasm, oromandibular dystonia, or spasmodic dysphonia. Writer’s cramp or occupational cramp is less common. When dystonia spreads to involve contiguous body parts, the term segmental dystonia is applied. The most common segmental dystonia is Meige syndrome in which blepharospasm is concomitant with oromandibular dystonia. Generalized dystonia represents involvements of bilateral legs and some other areas. On the other hand, in multifocal dystonia two or more noncontiguous parts are involved. In patients with hemidystonia one-half of the body is affected.

The etiologic classification of dystonia identifies primary, dystonia-plus syndromes, secondary, and heredodegenerative subsets.

3.2.3 Primary Dystonias

Primary dystonia is a pure dystonia, presenting dystonic postures, dystonic movements, and if any, dystonic tremor, but other neurologic abnormalities are not accompanied. Primary dystonias include familial and sporadic cases. Several causative genes have been identified, but in the most of primary dystonias the causes remain to be elucidated.

3.2.3.1 Early Onset Primary Dystonia

DYT1 is the typical early onset primary dystonia, begins in childhood or adolescence. DYT1 was first described by Oppenheim as “dystonia musculorum deformans” in 1911, thus also called as Oppenheim’s dystonia. The causative gene is TOR1A, being localized to chromosome 9q34, and encoding the protein torsin A (Ozelius et al. 1997). DYT1 is inherited in an autosomal-dominant manner with reduced penetrance of 30–40 %. Moreover, great intrafamilial variability is noted, ranging from severe generalized dystonia to mild writer’s cramp or even no dystonia at all. DYT1 is estimated to account for approximately 80–90 % of early onset dystonia in Ashkenazi Jews, and 15–50 % in non-Jews. The increased prevalence in Jews is attributed to a founder effect.

The average age of onset of DYT1 is approximately 12 years. Although onset ranges from 4 to 64 years, rare patients begin after age 26 years.

DYT1 usually starts in a leg or an arm as an action dystonia, being apparent with specific actions. When a leg is first affected, the child walks in a peculiar manner with inversion or eversion of the foot and abnormal flexion of the knee or hip. With arm involvement, writing is interfered by the finger curling, wrist flexion and pronation, and the elbow elevation. Dystonic tremor of the arm is frequently seen. The small minority of individuals have onset in the neck or a cranial muscle, presenting torticollis or blepharospasm.

Dystonic movements usually persist through life. Furthermore, in most patients with onset in a leg, dystonia progresses over several years. The contractions become less action specific and are present at rest, resulting in a fixed twisted posture. Going further, the dystonia spreads to other body parts to “generalized dystonia” involving other limbs and the trunk. In individuals who have onset in an arm, progression is variable and dystonia generalizes in approximately 50 %. Approximately 20 % of DYT1 is restricted to a single limb or the neck, usually as writer’s cramp. This occurs in a minority of individuals with adult onset.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree