Chapter 210 The Art of the Clinical Trial

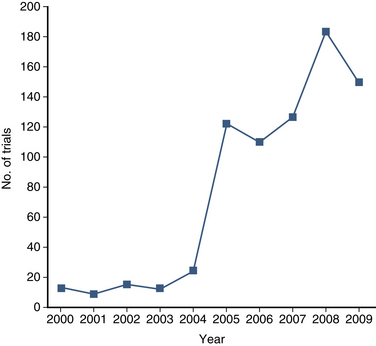

The purpose of the clinical trial is to determine the safety, efficacy, and/or effectiveness of a medical intervention. A clinical trial is, by definition, prospective and has a control group. The number of clinical trials that address diseases and interventions of the spine is increasing (Fig. 210-1). As discussed in Chapter 211, retrospective studies play a significant role in clinical spine surgery research; however, this chapter focuses exclusively on prospective studies.

Comparative Effectiveness

The term comparative effectiveness has become widely used since passage of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, which allocated $1.1 billion for new research projects aimed at understanding the differences among established medical treatments.1 Effectiveness differs from efficacy. An intervention is effective if it actually results in a satisfactory outcome when utilized broadly in the community. For example, an emergency tracheotomy might be efficacious when performed by trained personnel, but it might be ineffective or even dangerous when applied by untrained individual first responders. In general, a clinical trial is a carefully controlled scientific study that examines the efficacy, or safety, of an intervention. A clinical trial can evaluate the comparative effectiveness of an intervention versus an alternative, if and only if, the results are truly “generalizeable.” That is, the study population should represent the vast majority of patients with a particular condition, and, in the case of a surgical trial, the trial surgeons’ skill set should resemble that of an average practitioner. For example, transarticular C1-2 screws have been shown to be efficacious in treating C1-2 instability, but their effectiveness in the community has not been assessed in large practical trials involving surgeons without highly specialized spine surgery skills.2

Prospective Studies

A prospective cohort study is an investigation that includes two or more groups of similar patients who undergo different treatments and who are then assessed for a specific outcome. In spine surgery, most cohort studies are interventional in nature. The ongoing Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen (AO) Foundation–sponsored cervical spondylotic myelopathy (CSM) trial is a typical example. In this multicenter effort, patients with CSM undergo either ventral or dorsal surgery and are assessed using validated outcomes instruments at regular intervals. The nonrandomized study has accrued over 300 unselected patients and therefore provides some comparative effectiveness data.3 In this study, the baseline characteristics between treatment groups (ventral and dorsal surgery patients) are significant, and therefore differences in outcome observed following ventral and dorsal approaches cannot be necessarily attributed to the surgical approach. In fact, the degree of selection bias in many prospective cohort studies precludes any real conclusion regarding the primary research question. Selection bias might not always be related to the actual pathology. In a different prospective cohort study comparing 36 patients who underwent microsurgical resection with 46 patients who underwent stereotactic radiosurgery for treating vestibular schwannoma, the groups were compared using health-related quality of life (HR-QOL), functional, and radiographic tumor control outcome measures. Although the groups were similar with regard to tumor size preoperatively, the surgical group was significantly younger, thereby raising questions about the validity and generalizability of the results.4

Nonrandomized data have been reported to demonstrate significant differences between treatments 56% of the time, whereas RCTs show “significant” differences only 30% of the time.5 In addition to information bias, a publication bias, or the tendency of authors and editors to favor publication of studies with “positive” results, may exist. Systematic efforts to compare RCTs and nonrandomized studies on a number of medical and surgical topics have reached different conclusions.6 For nonrandomized trials to match the validity of an RCT, the inclusion and exclusion criteria must be clear, and known prognostic factors should be balanced with the utilization of objective outcome assessments.6,7

Randomized Controlled Trials

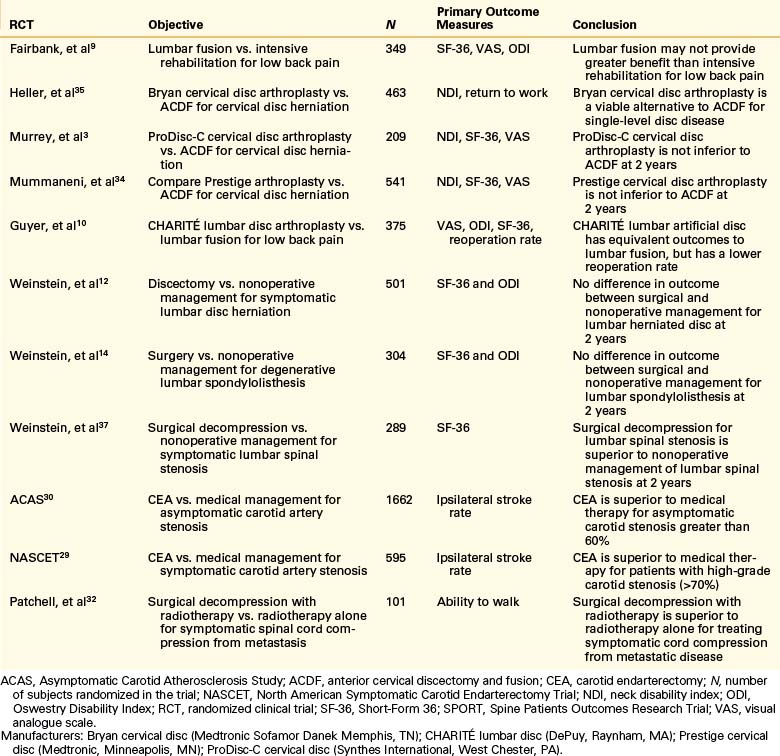

It is generally agreed that randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are the gold standard for determining whether one intervention is superior, equivalent, or inferior to an alternative.7 This is because all nonrandomized experiments might fail to balance important baseline prognostic variables, introducing bias into the results of the trial. It is estimated, however, that fewer than 1% of published papers in leading neurosurgical journals are RCTs.8 Some of the key completed RCTs (discussed in this chapter) that address spinal and other neurosurgical conditions are listed in Table 210-1.

There are a number of significant barriers to performing high-quality RCTs in spine surgery. One of these is the heterogeneity of spine diseases—the myriad symptoms caused by a single spinal anatomic abnormality and the clinical differences between patients with identical radiographic findings. The variation of the back pain population, for example, limits the ability to perform well-designed clinical trials comparing the nonoperative and operative treatments. Fairbank et al. performed an RCT (349 patients) comparing surgery to intensive rehabilitation therapy for back pain.9 Despite using a large sample size with validated and appropriate outcomes instruments, it was difficult for the investigators to draw conclusions about the surgical treatment of low back pain because the clinical entity was itself so heterogeneous. Making matters more complex, the most significant variables that result in patient heterogeneity are, often, unknown. A recent lumbar RCT comparing the CHARITÉ (DePuy, Raynham, MA) lumbar arthroplasty to anterior lumbar interbody fusion for the treatment of low back pain demonstrated statistically significant improvements in multiple outcome measures at 2 years.10 The study population, however, was not well defined and thus left clinicians to selectively choose ideal candidates for the study. Particularly when trials are designed to investigate a new technology and supported by corporate funding, this type of selection bias is common and can lead, in part, to a failure by a medical payer system (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services) to adopt and ultimately pay for the new technology despite its being supported by class I data.

One of the most important barriers to performing a surgical clinical trial is lack of equipoise. This term, popularized by Freedman in a classic 1987 paper, means “genuine uncertainty within the expert medical community” on the optimal approach for a certain medical condition.11 RCTs are ethical and feasible only when there is clinical equipoise between the treatment arms. Lack of clinical equipoise affected the National Institutes of Health (NIH)–sponsored Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT), an RCT that compared surgery versus nonoperative management for symptomatic lumbar disc herniation.12 The high crossover rate (30% from the nonoperative cohort to the operative cohort within 3 months), suggested that clinicians, patients, or both felt that surgery would provide a greater chance of clinical benefit after 6 weeks of failed conservative management. Conversely, almost as many patients randomized to receive surgery did not have an operation, indicating that patients had strong opinions favoring the role of conservative treatment when symptoms were mild or improving. In retrospect, the lack of clinical equipoise limited the ability of the study to detect better outcomes from surgery.13

Another SPORT RCT examined surgical versus nonsurgical treatment for degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis.14 Patients were included if they had neurogenic claudication or radicular leg pain, with spinal stenosis and degenerative spondylolisthesis on imaging. These patients were randomized to either nonoperative treatment or to decompressive laminectomy, with or without bilateral single-level fusion, with or without iliac crest bone grafting, and with or without pedicle screw instrumentation. This RCT also demonstrated high rates of crossover due to a lack of clinical equipoise. However, the methodology also demonstrated that heterogeneity of treatment can limit the ability to generalize results. In this trial, the underlying assumption that instrumented fusion, noninstrumented fusion, and decompression alone are equivalent may not be true, and therefore, the trial does not provide meaningful information about which treatment is optimal for the management of grade I spondylolisthesis.

By strict statistical criteria, an RCT should be analyzed by the intent-to-treat principle. That is, the outcomes are analyzed not by which treatment the patient actually received but rather by which treatment group they were randomly assigned to. This approach preserves the integrity of randomization, which theoretically balances confounding risk factors—both known and unknown. For example, in the asymptomatic carotid atherosclerosis study (ACAS), patients randomized to receive surgery were analyzed as such even if they had an angiographic complication after randomization (not related to surgery) or even if they did not undergo surgery at all.15 When crossover rates are high, the intention-to-treat analysis is less likely to detect a difference between two treatments.13 In the SPORT lumbar discectomy trial, the intent-to-treat analysis did not detect any benefit from surgery (crossover rate was 30%), although the as-treated analysis showed a significant benefit from surgery.12

The validity of a study analysis is also compromised when significant clinical data are missing. Response bias can occur when a subject does not fully complete questionnaires at each time point of the study. If the reasons that subjects do not participate (e.g., anger over surgical outcome) differ between the arms of the study, then a response bias exists. In the first published study of SPORT, the degree of missing data was between 24% to 27%.16,17

Another difficulty in designing RCTs for spine surgery is the learning curve associated with the clinical application of a new technology. If a practitioner has not performed a procedure with a new technology, it is likely the complication rate will be higher because of the learning curve associated with this technology. There has been a constant evolution of novel spine procedures, exemplified by the interbody fusion techniques. Current techniques for interbody fixation and fusion are changing at such a rapid pace that trials designed today to test these newer technologies might be obsolete and therefore irrelevant prior to the trials’ completion. A recent RCT compared use of femoral ring allograft versus a titanium cage in circumferential lumbar spine fusion.18 Clinical outcome was measured by the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI),19 Visual Analogue Score (VAS),20 and Short-Form 36 (SF-36)21 with 2-year follow-up. The trial found greater clinical improvements in all outcome scales with femoral ring allograft than for titanium cages. These results, and the higher cost of titanium cages, prompted the authors to state that use of cages in lumbar fusion was not justified. However, the surgical procedure performed in this study is now rarely performed. This “front-and-back” approach, using dorsal screw fixation in addition to retroperitoneal ventral approach for placement of interbody graft, has been replaced by a single approach to achieve circumferential fusion. More recent lumbar techniques include minimally invasive transforaminal techniques (possibly that reduce muscle trauma) often supplemented with cages and recombinant bone morphogenetic protein (BMP). Although this RCT was well-designed, its results cannot be applied to more recent lumbar fusion techniques.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree