Diagnosis of Skeletal Dysplasia |

Cervical Problems |

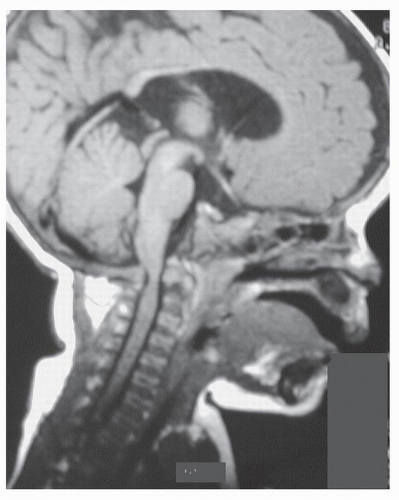

Achondroplasia |

Craniocervical stenosis (1, 2, 3, 4 and 5,7,8)

Developmental cervical subaxial stenosis (11) |

Pseudoachondroplasia |

Atlantoaxial instability due to odontoid hypoplasia and ligamentous laxity (12) |

Spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia |

Atlantoaxial instability due to odontoid hypoplasia or os odontoideum and ligamentous laxity (13,14,15,16) |

Spondylometaphyseal dysplasia |

Atlantoaxial instability due to odontoid hypoplasia and ligamentous laxity (18) |

Kniest’s dysplasia |

Atlantoaxial or occipitoatlantal instability (17, 18, 19) |

Metaphyseal chondrodysplasia |

Atlantoaxial instability due to ligamentous laxity (21,22) |

Metatropic dysplasia |

Atlantoaxial instability due to odontoid hypoplasia or lateral mass defect of C2 (23,24) |

Chondrodysplasia punctata |

Atlantoaxial instability due to os odontoideum (Conradi-Hunermann type) (22)

Subaxial canal stenosis (rhizomelic type) (25)

Coronal clefts or hypoplasia of the vertebral bodies (26) |

Diastrophic dysplasia |

Kyphosis due to hypoplasia of vertebral bodies, hypotonia, and/or spina bifida (28,29)

Atlantoaxial instability due to dysmorphism of the odontoid process(30) |

Camptomelic dysplasia |

Excessive lordosis and/or kyphosis (34,35) |

Mucopolysaccharidosis |

|

Type 1 Hurler’s syndrome |

Odontoid dysplasia (37)

Abnormal soft tissue formation around the tip of the odontoid (37,38) |

|

Type 2 Hunter’s syndrome |

Cervical canal stenosis with thickening of the soft tissue (dura) posterior to the odontoid (39,40) |

|

Type 4 Morquio’s syndrome |

Atlantoaxial instability due to odontoid hypoplasia or os odontoideum with soft tissue thickening (41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48 and 49) |

Oculoauricular vertebral dysplasia |

Atlantoaxial instability due to odontoid hypoplasia

Occipital-C1 instability

Occipitalization of C1

Failure of segmentation or formation of vertebrae (50) |

Osteopathia striata |

Kyphosis due to dysplasia and hypotonia (51) |

Pyknodysostosis |

Kyphosis due to C2 and/or C3 spondylolysis (52, 53) |

Thanatophoric dysplasia |

Platyspondyly

Atlantoaxial instability due to odontoid hypoplasia (55) |

Multiple epiphyseal dysplasia |

Atlantoaxial instability due to os odontoideum (56) |

Osteopetrosis |

Spondylolysis (57)

Foramen magnum narrowing (58) |

Osteopoikilosis |

Canal stenosis (59) |

Cleidocranial dysostosis |

Basilar impression with enlarged foramen magnum (60)

Atlantoaxial instability (61) |

Spondyloepimetaphyseal dysplasia |

Atlantoaxial instability due to odontoid hypoplasia and ligamentous laxity (62) |