BACKGROUND

Discussion of the mental health of ‘older people’ most often focuses on those aged 65 years and over – that is, above the most frequent, statutory retirement age in Western nations1. This is arbitrary and culture-specific, and for research in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) the cut-point is often set at 60 years. According to the Global Burden of Disease report, neuropsychiatric disorders account for 13.5% of the global burden of disease, and 27.5% of that attributable to non-communicable diseases (NCD)2, while for those aged 60 years the proportion is smaller – 7.4% of the global burden of disease and 8.3% of that arising from non communicable diseases. While the prevalence of dementia rises sharply in later life, doubling with every five-year increase of age, that of depression is, perhaps, a little lower than among younger adults. Many people with chronic severe psychosis do not survive into old age, and there is a small incidence of late-onset psychosis. However, mental ill health in later life poses particular challenges for public health. Health profiles among older people, particularly the oldest old, are somewhat distinct, with mental ill health often complicated by co-morbidity with chronic physical and cognitive disorders, a combination that is particularly strongly associated with disability and dependency. Beyond the challenges of living with chronic disease and disability, further obstacles to the maintenance of good mental health into late life include retirement (loss of occupational role, status and income) and a shrinking social network (loss of spouses, siblings and friends through bereavement)1.

Older people, their health and social welfare, have for too long been under-prioritized in global public health policy. This is now changing with increasing recognition, over the past 20 years, of their growing importance in LMIC3. Demographic ageing is proceeding more rapidly than first anticipated in all world regions, particularly China, India and Latin America4. The proportion of older people increases as mortality falls and life expectancy increases. Population growth slows as fertility declines to replacement levels. In the 30 years up to 2020 the oldest sector of the population will have increased by 200% in LMIC as compared to 68% in the developed world5. By 2020, two-thirds of all those over 60 will be living in LMIC6, where, in the accompanying health transition, non-communicable diseases assume a progressively greater significance. NCDs are already the leading cause of death in all world regions apart from sub-Saharan Africa. Of the 35 million deaths in 2005 from NCDs, 80% will have been in LMIC7. This is partly because most of the world’s older people live in these regions. However, changing lifestyles and patterns of risk exposure also contribute. Among the NCDs, dementia and depression in older people have only fairly recently begun to be given the attention that they deserve in population-based research in LMIC. The purpose of this chapter is to describe the contribution of this research to our understanding of the epidemiology of these disorders, to contextualize these findings with what has been observed in high-income countries (HIC), and to describe some of the methodological challenges to be overcome in conducting this research in varied cultural settings.

‘Depression’, as a diagnosis applied in clinical settings, generally requires persistent and pervasive low mood and/or loss of pleasure, accompanied by other characteristic symptoms (including guilt, sleep and appetite disturbance), sufficient to cause significant distress and disability8. However, mood states do not fall naturally into discrete categories, but instead represent a spectrum from normality through increasing degrees of morbidity. As with any ‘cut-off’ applied to an underlying continuum (e.g. hypertension), the prevalence of the disorder depends substantially on the threshold that is selected. Severe depressive disorders have a high individual impact on those affected, but are rare. Milder syndromes have a lower individual impact but, given their higher prevalence, may have a substantially greater public health impact.

The Cross-Cultural Validity of the Assessment and Diagnosis of Late-Life Depression

There is reasonably strong evidence to support the cross-cultural validity of measurement of depression among older people. This has been most extensively studied with respect to the 12-item EURO-D depression symptom scale, which has been shown to have a similar factor structure in 14 European sites9, as well as in India, China and Latin America10. Measurement invariance was later formally established for the EURO-D across 10 European countries in the SHARE study, using confirmatory factor analysis to confirm a common factor structure and Mokken analysis to confirm a common hierarchical relationship between items11. The subsequent demonstration of higher levels of EURO-D depression symptoms among older people in three countries sharing a ‘Latin’ ethnolingual heritage; France, Spain and Italy; after standardizing for age, sex, education and cognitive function suggested a possible role of culture in determining risk12. In terms of clinical diagnostic assessments of depression, the strongest evidence for cross-cultural validity exists for the Geriatric Mental State and its AGECAT algorithm, probably the most widely used such assessment internationally13. The instrument has been validated against most major diagnostic systems, but primarily only in HIC settings13. As part of the 10/66 Dementia Research Group’s pilot studies in 26 centres in Latin America, India, China, Nigeria and Russia, its Stage 1 AGECAT depression algorithm was found to have sensitivity varying between 89% and 100% by region against a criterion of MADRS score of 1810. Specificity was difficult to establish, since depression was not formally excluded from the control groups, whose main purpose was to validate the dementia component of the algorithm. Nevertheless, the prevalence of AGECAT depression was negligible in these groups other than in Latin American sites10. The AGECAT depression algorithm was subsequently validated in Hefei City, China, where there was a diagnostic agreement of 83.6% and a Kappa of 0.67 against Chinese psychiatrists’ independent gold standard diagnostic evaluation14.

In the absence of qualitative research demonstrating the ecological validity of late-life depression as a pathological construct, the evidence for the cross-cultural validity of the commonly used ICD-10 and DSM-IV clinical diagnostic criteria among older people in LMIC is limited mainly to concurrent validation, that is from observations of cross-sectional associations with disability and impaired quality of life. In Nigeria15 and Brazil16, depression diagnosed was associated with high levels of social disability and impaired quality of life. In Mexico, Peru and Venezuela, high levels of disability were also identified in those with sub-syndromal depression identified with the EURO-D scale, suggesting a considerable prevalence (an additional 23–24%) of clinically significant disorder beyond the established diagnostic boundaries17. More research is needed to determine if these findings are typical of less developed regions in general.

The Prevalence of Late-Life Depression

The prevalence of late-life depression has been extensively studied in developed countries in the European, North America and Asia Pacific regions18,19. The main influence on prevalence is the criterion used to make the diagnosis20. According to rigorous research diagnostic criteria such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) major depression and the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10) depressive episode late-life depression is uncommon with a weighted mean prevalence of only 1.8%; when all those with clinically relevant symptoms are included, the weighted mean prevalence rises to 13.3%18. The relative lack of epidemiological data from LMIC is particularly striking – in the two systematic reviews, all of the 34 publications covering the period 1989–9618 and the 122 papers covering the period 1993–200419 described research carried out in high-income countries. Recently published prevalence studies from Nigeria, Brazil, Latin America and China have helped to redress this imbalance. Two publications report an exceptionally high prevalence of DSM-IV major depression in Nigeria (7.1%)15 and of ICD-10 depressive episode in Brazil (19.2%)16. The 10/66 Dementia Research Group has also recently reported on the prevalence of ICD-10 and DSM-IV depression in three Latin American countries, Mexico, Peru and Venezuela, which in these settings was closer to that reported in HIC, the prevalence of DSM-IV depression varying between 1.3 and 2.8% and that of ICD-10 depression between 4.5 and 5.1%17. Conversely, the prevalence of GMS/AGECAT depression in Hefei City, China, was only 2.2%, roughly five times lower than in European studies using the same assessment and case definition14. The prevalence in a rural village in Anhui province was slightly higher, at 6.0%21.

In the few studies in LMIC to have examined this issue, treatment of clinically significant depression seems to be severely sub-optimal – in the 10/66 Latin American studies only 24.1% of those in urban Peru with a current ICD-10 depressive episode, 18.8% in rural Peru, 11.8% in urban Mexico, 4.4% in rural Mexico and 19.6% in Venezuela reported ever having received in-patient or out-patient treatment for depression17: In Nigeria, only 37% of lifetime cases had received any treatment15.

Sociodemographic Correlates of Late-Life Depression

The few studies to have assessed prevalence of depressive disorders across the adult age range suggest an increase from young to mid-adult age groups, followed by a fall in prevalence for older people within a decade of the retirement age22,23. A striking trend in the opposite direction has been observed in Nigeria, the authors speculating that lack of social protection for older people may have contributed to their much higher prevalence of DSM-IV major depressive disorder.15 Studies from HIC that have focused upon depressive symptoms and broader depressive syndromes also indicate either an increase in their frequency24 or stability with increasing age25. The exclusion, in some diagnostic criteria, of symptoms thought to be attributable to bereavement and physical illness may account in part for the apparent lower prevalence of depressive disorders in older people. In European studies, the prevalence of late-life depression is consistently higher in women compared to men12,24, but the gender difference tends to be smaller than that found in mid-life. In European studies, the effect of gender is consistently modified by marital status, with marriage being protective for men but associated with higher risk among women24. A higher prevalence of late-life depressive disorder among women is also a consistent finding in studies in LMIC, replicated in Brazil16, Nigeria15 and the 10/66 Dementia Research Group Latin American studies17. However, in the 10/66 studies the association with female gender was entirely confounded by socioeconomic status and physical impairment, both of which were more common in women – a similar finding was reported in the SABE studies in six Latin American cities, although depression in that study was defined by a cutpoint on the Geriatric Depression Scale rather than a clinical diagnosis26.

There have been many reports from cross-sectional community surveys, from a variety of cultures, of associations between late-life depression and socioeconomic disadvantage, for example with respect to educational level, occupational social class and income19. These are highly correlated variables, and it is difficult to determine the effect of one independent of the others. Reverse causality is possible – those whose adult life has been scarred by depression may experience lifelong occupational and economic disadvantage. Findings from LMIC are currently inconsistent – suggestive trends in the direction of an association between socioeconomic disadvantage and depression were observed, rather inconsistently, in the five sites in the three 10/66 Latin American countries17. Level of education seemed to be more relevant than income or wealth. Food insecurity was strongly associated with depression in Mexico, with non-significant trends in Peru and Venezuela. Depression in Hefei City, China was also positively associated with economic disadvantage14. Unusually, in Nigeria, an association was observed in the opposite direction, with the highest prevalence of depression among older people with the highest economic status15.

The Aetiology of Late-Life Depression

To date there have been no prospective studies of potential aetiologic factors for late-life depression in LMIC. There have, however, been a large number of well-designed cohort studies carried out in Europe and North America, the findings from which have been subject to systematic review19,27 and quantitative meta-analysis27. There is strong and fairly consistent evidence to support an increased risk for incident depression associated with female gender, disability, prior depression, bereavement and sleep disturbance. Disability is probably the most salient of these factors. Prospective studies in older adults have consistently indicated a very strong association between disability at baseline and the subsequent onset of depression28–32. In one of these studies31 the population attributable fraction was as high as 0.69. In general, the level of disability associated with a health condition, rather than the nature of the pathology mediates the risk for depression31,33,34. Stroke may be an exception as some studies show persistence of associations with depression after adjustment for disability35. Three population-based studies have suggested an interaction between disability and social support, with the strongest effect of disability in those with the least social support31,32,36. However, there is also strong evidence for causal pathways leading from depression to the progression or emergence of disability37,38. Cross-sectional data from the 10/66 studies in Mexico, Peru and Venezuela also support a strong association between limiting physical impairments and depression, with a past history of depression being the other consistently observed association17.

One of the more consistent findings from previous Western research is the apparent salience of contact with friends, in particular intimate, confiding relationships to mood and morale in older people. While older people typically receive instrumental support from spouses and relatives, they value friends for companionship and emotional support. In the longitudinal Gospel Oak study, no contact with friends was the only social support variable prospectively associated with the onset of depression31. The social environment for older people is affected by the ageing process. Social networks deteriorate with increasing age consequent upon bereavement. Social engagement, such as visiting friends, is impaired in those with disability. Women typically have more supportive and extensive networks of friends than men. Married older men cite their wife as their main confidant, whereas women more often cite a friend outside the home. There have been few such studies conducted in other cultural settings, but in a cross-sectional study in Cuba, social networks, mainly centred around children and extended families, were associated with fewer depressive symptoms in both older men and women39.

Dementia is a syndrome due to disease of the brain, usually chronic and progressive, in which there is disturbance of multiple higher

cortical functions, including memory, learning, orientation, language, comprehension and judgement. Diagnosis is on the basis of decline in cognitive function and independent living skills. There are many underlying causes. Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies and frontotemporal dementia are the commonest. Mixed pathologies may be the norm. Studies in developed countries have consistently reported Alzheimer’s disease (AD) to be more prevalent than vascular dementia (VaD)40. Early surveys from SouthEast and East Asian countries provided an exception with an equal distribution of AD and VaD40. More recent research suggests this situation has now reversed41,42. This may be due to increasing longevity and better physical health: AD, whose onset is in general later than VaD, increases as the number of very old people increases; while better physical health reduces the number of stroke sufferers and thus the number with VaD41. This change also affects the gender balance among dementia sufferers, increasing the number of females and reducing the number of males. Some rare causes of dementia (subdural haematoma, normal pressure hydrocephalus, hypercalcaemia and deficiencies of thyroid hormone, vitamin B12 and folic acid) may be treated effectively – these may, theoretically, be overrepresented in LMIC, but their contribution particularly in young onset cases has yet to be investigated.

The Validity of Dementia Diagnosis Across Cultures

The validity of the construct of dementia in less-developed settings is supported by three qualitative studies in India. The features of dementia were widely recognized, and named43–45. However, there was no awareness of dementia as an organic brain syndrome, or medical condition. Rather, it was perceived as a normal, anticipated part of ageing. The consequences are little help seeking from formal medical care services44, no structured training on the recognition and management of dementia at any level of the health service, and no constituency to advocate for more responsive dementia care services45. Behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) can lead to stigma and blame attaching to the carers as well as the person with dementia46. In India, likely causes were cited as ‘neglect by family members, abuse, tension and lack of love’44, and carers tended to misinterpret BPSD as deliberate misbehaviour45.

The validity of methods used in cross-cultural research is fundamental to the success of the enterprise. Without this, informative cross-cultural comparisons are impossible. Many potential obstacles needed to be overcome47. Those with little or no education may appear to ‘fail’ on cognitive screening tests even in the absence of cognitive impairment or decline. The task may be unfamiliar to them, or the information requested irrelevant. Tasks involving literacy, numeracy or drawing are particularly problematic, but in practice any cognitive item for which the probability of a correct response is strongly influenced by education will tend to be biased. Culture, including language, may also influence the salience and feasibility of cognitive items, and their relative difficulty. Cultural influences, as we shall see, may also impact on the assessment of social or occupational disability, since the normal roles of older people may vary considerably between cultures.

The history of cross-cultural research in dementia is characterized by careful attention to the applicability and validity of the measures employed. In the 1990s, the National Institute of Aging funded US–Nigeria and US–India studies developed48 or adapted49,50 cognitive tests to render them suitable and normed for the cultural setting, and also developed culture-specific assessments of functional impairment51. In the wake of these efforts, the 10/66 Dementia Research Group carried out pilot studies in 26 centres from 16 LAMIC in Latin America and the Caribbean, Africa, India, Russia, China and SE Asia, demonstrating the feasibility and validity of a one-phase culture and education-fair diagnostic protocol for population-based research52. The Geriatric Mental State (a structured clinical interview assessing dementia, depression and psychosis syndromes)53, the Community Screening Instrument for Dementia (a cognitive test, and informant interview for evidence of intellectual and functional decline, used in the US–Nigeria study)48 and the modified CERAD 10-word list-learning task (used in the US–India study) each independently predicted dementia diagnosis49. A probabilistic algorithm derived in one-half of the sample from all four of these elements performed better than any of them individually; applied to the other half of the sample it identified 94% of dementia cases with false positive rates of 15%, 3% and 6% in the depression, high education and low education groups52. This algorithm (the 10/66 Dementia Diagnosis) was ‘education-fair’ in that the false positive rate among those with low levels of education was low, and ‘culture-fair’ in that equivalent validity was established for a wide variety of countries, languages and cultures. It therefore provides a sound basis for dementia diagnosis in clinical and population-based research.

The prevalence of DSM-IV dementia was strikingly low in the US–Nigeria and US–India studies54,55. The validity of this criterion, developed in the USA, had not been established in LMIC settings. In the 10/66 Dementia Research Group studies, a computerized application of the DSM-IV criterion was devised and validated56. The relative concurrent and predictive validity of the two diagnostic approaches, 10/66 Dementia and DSM-IV dementia, could thus be compared. In the Cuban 10/66 population-based study, the 10/66 dementia diagnosis agreed better with Cuban clinician diagnoses than did the DSM-IV computerized algorithm, which missed many recent onset and mild cases56. An essential feature of the dementia syndrome is that it is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder; the principal rationale for an early diagnosis is that it alerts the person concerned and their family to the probability of future deterioration. The 10/66 Dementia Research Group confirmed the predictive validity of their diagnosis in the population-based study sample in Chennai, South India, identifying a high mortality rate, and greater cognitive and functional decline over three years among 10/66 dementia cases and those with cognitive impairment but no dementia57. There was also clear evidence of clinical progression and increasing needs for care among the large majority of 10/66 dementia cases. The strong predictive validity of the 10/66 dementia diagnosis was consistent with a lack of sensitivity of the DSM-IV criterion to mild to moderate cases, and, thus, with the notion that it may underestimate prevalence in less developed regions57.

The Prevalence and Incidence of Dementia

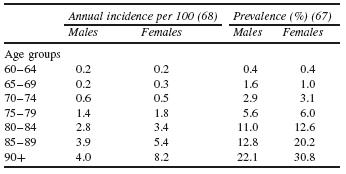

Dementia is largely a disease of older persons; only 2% of cases are to be found in those aged under 65 years. After this the prevalence doubles with every five-year increment in age. The EURODEM meta-analysis of European population-based studies from the 1990s used data from 11 studies carried out in eight European countries58. Prevalence was consistent across sites; the pooled prevalence for males and females is shown in Table 114.1.

The annual incidence rates reported in the EURODEM meta-analysis59 are roughly one-quarter of the point prevalence

Table 114.1 EURODEM meta-analysis of European population-based studies: pooled prevalence for males and females

(Table 114.1), suggesting an average disease duration (from onset to death) of four years. Clinical studies have suggested a duration of five to seven years from diagnosis. A recent meta-analysis60 of the age-specific incidence of all dementias was based on data from 23 published studies. The incidence of both dementia and AD rose exponentially up to 90 years, with no sign of levelling off. The incidence rates for VaD varied greatly from study to study, but the trend was also for an exponential rise with age. While there was no sex difference in dementia incidence, for the oldest old the incidence of AD was higher in women, and for the younger old the incidence of VaD was higher in men.

In LMIC there is more uncertainty as to the frequency of dementia, with few studies and widely varying estimates47. Early onset cases are again rare, although this may be changing in those world regions where HIV/AIDS is endemic. In 2004, Alzheimer’s Disease International convened a panel of international experts to review the global evidence on the prevalence of dementia, and to estimate the prevalence of dementia in each world region, the current numbers of people affected, and the projected increases over time (Lancet/ADI estimates). A tendency previously noted for age-specific prevalence to be lower in LMIC than in the developed north47,54,55 was supported by the consensus judgement of the expert panel61. Differences in survival could only be part of the explanation, as estimates of incidence in some studies62,63 were also much lower than those reported in the West. Differences in levels of exposure to environmental risk factors may also have contributed, with low levels of cardiovascular risk64 and hypolipidaemia65,66 in some developing countries suggested as explanations. Other potential risk exposures will be more prevalent in LMIC, for example anaemia associated with AD in rural India67. High infant mortality may contribute to population differences in dementia frequency; constitutional and genetic factors that confer survival advantage in early years may protect against neurodegeneration or delay its clinical manifestations. It seems plausible that as patterns of morbidity and mortality converge with those of the developed West, then dementia prevalence in LMIC will do likewise68. While studies of secular trends in Sweden, 1947 to 195269 and in the US, 1975 to 198070, suggested no change in the prevalence of dementia over time, it is possible that age-specific prevalence of dementia in HIC might fall in the future because of reduced incidence linked to improvements in cardiovascular health or

rise, due to reduction in mortality among those with dementia.

However, the Lancet/ADI estimates were described as ‘provisional’, given that prevalence data were lacking in many world regions, and patchy in others, with few studies and widely varying estimates61. Coverage was good in Europe, North America and in developed Asia-Pacific countries: South Korea, Japan, Taiwan and Australia. Several studies have been published from India and China, but estimates were too few and/or too variable to provide a consistent overview for these huge countries. There was a particular dearth of published epidemiological studies in Latin America71–73, Africa54, Russia, the Middle East and Indonesia. Therefore, there was a strong reliance upon the consensus judgement of the international panel of experts for LMIC.

The 10/66 Dementia Research Group prevalence studies

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree