The Deep Tendon or Muscle Stretch Reflexes

When a normal muscle is passively stretched, its fibers resist the stretch by contracting. Reflexes elicited by application of a stretch stimulus to either tendons or periosteum, or occasionally to bones, joints, fascia, or aponeurotic structures are usually referred to as muscle stretch or deep tendon reflexes. The reflex is caused by sudden muscle stretch, brought about by percussion of its tendon. Occasionally, the tendon is stretched by percussing a structure to which it is attached, as in the jaw jerk. Because of their critical roles in maintaining an erect posture, the extensor muscles of the legs, quadriceps and calf muscles, have better developed stretch reflexes than the flexors.

The term deep helps separate these reflexes from the superficial or cutaneous reflexes, which are quite different. The term deep tendon reflex (DTR) was introduced in 1875, and since at least 1885 some authorities have criticized it. The term DTR is in much wider use than muscle stretch reflex, and for both pragmatic and anti-pedantic reasons, the DTR abbreviation will be used in this text.

The primary problem areas in eliciting DTRs are poor tools and poor technique. These reflexes are best tested using a high-quality rubber percussion hammer. To properly obtain a reflex, a crisp blow must be delivered to quickly stretch the tendon. A heavy, high-quality reflex hammer is immensely helpful for this task. Proper technique is much more difficult to describe than to demonstrate. The hammer strike should be quick, direct, crisp, and forceful, but no greater than necessary. The most effective blow is delivered quickly with a flick of the wrist, holding the handle of the hammer near its end and letting it spin through loosely held fingertips. Putting the index finger on top of the handle and using primarily elbow motion, common faults, make it much harder to achieve adequate velocity at the hammer head. Another common mistake is “pecking”: striking the tendon with a timid, decelerating blow, pulling back at the last instant.

The patient should be comfortable, relaxed, and properly positioned. It may help relaxation to divert the patient’s attention with light conversation. Sometimes, as in the ankle reflex, positioning includes passively stretching the muscle slightly. An adequate stimulus must be delivered to the proper spot. Reinforcement methods are necessary if the reflex is not obtainable in the usual way. The part of the body to be tested should be in an optimal position for the response, usually about midway in the range of motion of the muscle to be tested. In order to compare the reflexes on the two sides of the body, the position of the extremities should be symmetric. During the reflex examination, the patient should keep the head straight, since looking to one side may alter reflex tone, especially in the arms (tonic neck reflex). The DTRs may be influenced to some degree by voluntary mental effort. Merely by concentrating some individuals are able to somehow alter reflex excitability. Mentally induced reflex asymmetry is possible and may be clinically relevant in some cases.

TABLE 28.1 The Commonly Elicited Deep Tendon (Muscle Stretch) Reflexes | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The examiner can feel as well as see the contraction. Placing one hand over the muscle is often useful, especially when responses are sluggish. A reflex quadriceps contraction can sometimes be felt even when insufficient to produce visible contraction or knee movement. The activity of a reflex is judged by the speed and vigor of the response, the range of movement, and the duration of the contraction. An absent reflex often makes a dull, thudding sound when the tendon is struck.

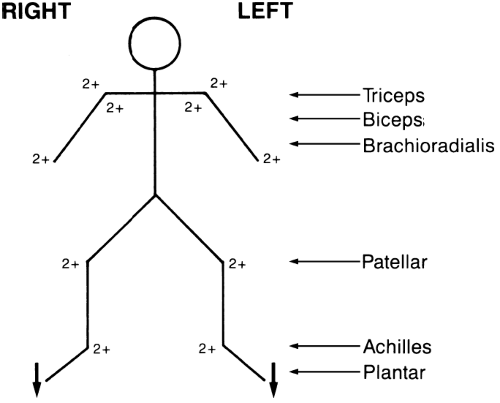

The DTRs usually examined include the biceps, triceps, brachioradialis, knee (quadriceps), and ankle (Achilles) tendon reflexes. Table 28.1 summarizes the reflex levels. Reflexes may be graded as absent, sluggish or diminished, normal, exaggerated, and markedly hyperactive. For the purposes of clinical note taking, most neurologists grade the DTRs numerically, as follows: 0 = absent; 1 + (or +) = present but diminished; 2+ (or + +) = normal; 3+ (or + + +) = increased but not necessarily to a pathologic degree; and 4+ (or + + + +) = markedly hyperactive, pathologic, often with extra beats or accompanying sustained clonus. The “+” after the number is more traditional than informative, and is sometimes omitted. Signs are sometimes used to indicate subtle asymmetry, but generally a grade of 2 means the same as 2+. Another level, trace (or +/−), is frequently added to refer to a reflex, most often an ankle jerk, that appears absent to routine testing but can be elicited with reinforcement. Some add a grade of 5 + for the patient with extreme spasticity and clonus. In the 0 to 4 scale, level 1 + DTRs are still normal but somewhat sluggish and difficult to elicit, hypoactive but in the examiner’s opinion not pathologic. Grade 3+ reflexes are “fast normal,” quicker than 2+, sometimes very quick, but not accompanied by any other signs of upper motor neuron pathology such as increased tone, upgoing toes, or sustained clonus. Normality of the superficial reflexes, normal lower-extremity tone, and downgoing toes are reassuring evidence of fast normal rather than pathologically quick reflexes. Some use 3+ to indicate the presence of spread or unsustained clonus, with all other normal reflexes, even very fast ones, labeled as 2+. Grade 4+ reflexes are unequivocally pathological. The speed of the response is very fast, the threshold low, the reflexogenic zone wide, and there are accompanying signs of corticospinal tract dysfunction. Other scales are in use, but not widely. Reflexes may be charted in several ways, for example, as shown in Table 28.2, or as in Figure 28.1.

When reflexes are very active, responses may occur from muscles that have not been directly stretched, even in normal patients. The response may involve adjacent or even contralateral muscles, and the contraction of one muscle may be accompanied by contraction of other muscles. This is referred to as spread, or irradiation, of reflexes. It is normal for percussion of the brachioradialis tendon to also cause slight finger flexion. In the presence of spasticity and hyperreflexia, contraction of the biceps or brachioradialis may be accompanied by pronounced flexion of the fingers and adduction of the thumb. Extension of the knee may be accompanied by adduction of the hip, or there may be bilateral knee extension. Judging how much spread is still within normal limits can be difficult. Under some circumstances, the expected response to percussion of a tendon is absent, but muscles innervated by adjacent spinal cord segments contract instead (e.g., inverted brachioradialis reflex). On other occasions, a reflex is absent and percussion of the tendon causes an inverted or

paradoxical contraction, e.g., elbow flexion on attempted elicitation of the triceps reflex (see Inverted and Perverted Reflexes further on).

paradoxical contraction, e.g., elbow flexion on attempted elicitation of the triceps reflex (see Inverted and Perverted Reflexes further on).

TABLE 28.2 Method of Recording the Commonly Tested Deep Tendon (Muscle Stretch) Reflexes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

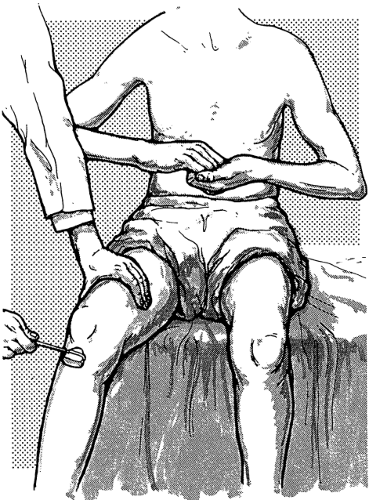

In some patients, DTRs may be markedly diminished, or even apparently absent, although there is no other evidence of nervous system disease. Under such circumstances, reinforcement techniques are often useful. Reflex reinforcement probably involves supraspinal, fusimotor, and longloop mechanisms. A reflex can be reinforced or brought out using several methods. In the Jendrassik maneuver, the patient attempts to pull the hands apart with the fingers flexed and hooked together, palms facing, as the tendon is percussed (Figure 28.2). The effect is very brief, lasting only 1 to 6 seconds, and is maximal for only 300 milliseconds. The Jendrassik maneuver is obviously only useful for lower-extremity reflexes. Other techniques include having the patient clench one or both fists, firmly grasp the arm of the chair, side of the bed, or the arm of the examiner. Reinforcement may also be carried out by having the patient look at the ceiling, grit the teeth, cough, squeeze the knees together, take a deep breath, count, read aloud, or repeat verses at the time

the reflex is being tested. A sudden loud noise, a painful stimulus elsewhere on the body—such as the pulling of a hair or a bright light flashed in the eyes—may also be a means of reinforcement.

the reflex is being tested. A sudden loud noise, a painful stimulus elsewhere on the body—such as the pulling of a hair or a bright light flashed in the eyes—may also be a means of reinforcement.

FIGURE 28.1 • Alternate method of recording the commonly tested muscle stretch reflexes. For grading, see text and Table 28.2. |

Procedures other than distraction are also helpful in reflex reinforcement. A slight increase in tension of the muscle being tested may reinforce the reflex response. A simple and effective method to reinforce a knee or ankle jerk is to have the patient maintain a slight, steady contraction of the muscle whose tendon is being tested (e.g., slight plantar flexion by pushing the ball of the foot against the floor or the examiner’s hand to reinforce the ankle jerk). The patient may tense the quadriceps by extending the knee slightly against resistance as the knee jerk is being elicited. Reinforcement may increase the amplitude of a sluggish reflex or bring out a latent reflex not otherwise obtainable. Reflexes that are normal on reinforcement, even though not present without reinforcement, may be considered normal. Slight muscle contraction due to inability to relax may be one reason for the slightly hyperactive reflexes often seen in patients who are tense or anxious.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree