Chapter 131 The Geriatric Patient

Surgical morbidity and mortality have been shown to be greater in the elderly patient.1 Although this subset of patients is very heterogeneous, the general decline in physiologic reserve and presence of coexistent disease are likely primarily responsible for this finding.2,3 The spine surgeon should be able to recognize specific surgical risk factors and develop an appropriate treatment plan that accommodates the specific needs of elderly patients.

Organ Systems

Cardiovascular System

It has been reported that at autopsy 50% of patients older than 70 years of age have significant cardiovascular disease. The cardiac risk index, a commonly used assessment tool, incorporates myocardial infarction in the past 6 months, uncompensated congestive heart failure, aortic stenosis, nonsinus rhythm greater than five premature ventricular contractions per minute, diabetes mellitus, and age older than 70 years as major risk factors for postoperative cardiac complications of noncardiac surgery4 (Box 131-1).

The basic cardiovascular workup in patients older than 65 years of age should include a thorough history and physical examination and a baseline electrocardiogram. Myocardial infarction, unaccompanied by recognized symptoms, occurs in as much as 10% of elderly patients.5 Reports of syncope or dyspnea are the most suggestive symptoms of this event. Peripheral vascular disease is often present with coronary artery disease and may complicate the diagnosis of neurogenic claudication. Absent peripheral pulses or a history of transient ischemic attacks or stroke should lead to a more comprehensive cardiac workup.

In patients with unstable angina, elective spinal surgery is clearly contraindicated. Patients with well-controlled stable angina, however, have only a slightly increased risk for perioperative cardiac complications, and may therefore be considered for surgery.6 Moderate to severe congestive heart failure is associated with a significant perioperative risk.7–9 Jugular venous distention and peripheral edema are suggestive signs, whereas a history of dyspnea on exertion and orthopnea are symptoms of a more severe form of congestive heart failure.

Respiratory System

Elderly patients are at particular risk for perioperative pulmonary complications for several reasons. Decline in pulmonary function and reserve, underlying chronic obstructive disease and bronchitis, lack of mobility or bed rest associated with spinal surgery, and airway obstruction all can lead to significant morbidity or mortality for these patients.10,11 In a series of 100 patients older than 70 years of age, approximately 40% of those without a history of lung disease had abnormal pulmonary function.12 Pulmonary function tests (spirometry) should be obtained for patients older than 65 years of age or with a history of obstructive lung disease if a ventral approach is being considered.13

A forced expiratory volume in 1 second of less than 50% of the predicted value does not suggest an increased risk of postoperative mechanical ventilation, but combined with dyspnea at rest and arterial hypoxemia, it is an established risk factor.14 Room air arterial blood gas should be tested in elderly patients with lung disease, as well as those with a history of shortness of breath, poor exercise tolerance, orthopnea, or excessive smoking. Elevated partial pressure of carbon dioxide (Pco2) reflects a loss of pulmonary reserve. A preoperative Pco2 of greater than 45 mm Hg is associated with an increased incidence of postoperative pulmonary complications,15 and patients with a Pco2 of greater than 50 mm Hg often require a period of postoperative mechanical ventilation.16

Renal System

Decline of renal function in the elderly is more consistent than that of other organ systems.17 In geriatric patients, serum creatinine levels may be artificially low because of decreased production, caused by a shrinking muscle mass. For this reason, creatinine clearance is the preferred test for patients suspected of having significant renal disease. The effect of chronic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use on the kidney may also contribute to the decline in renal function with advancing age. These drugs can decrease renal blood flow, adding to an already diminished glomerular filtration rate.18 This has clinical significance in the perioperative patient because water homeostasis may be difficult to achieve in elderly patients, leaving them prone to hyponatremia and volume overload. The use of isotonic fluids, restriction of free water, and careful administration of diuretics may be helpful.

Other Sources of Morbidity

Advanced age itself is a risk factor for deep venous thrombosis.1 Given the risks associated with bleeding after spine surgery, many surgeons are hesitant to anticoagulate, even with deep venous thrombosis demonstrated by venous Doppler ultrasonography. Such patients can be considered for vena cava filter placement or delayed (5 to 7 days after surgery) anticoagulation. All patients should receive aggressive physical therapy with early ambulation and range-of-motion exercises. Pneumatic compression devices should be used on all patients during their period of bed rest.

Malnutrition is associated with increased morbidity and mortality in elderly surgical patients.19 Dietary supplements should be added to the hospital diet of patients with reduced postoperative caloric intake to achieve a protein intake of 1 to 2 g/kg/day.

Advanced age is also a risk factor for wound infection. A sixfold increase in clean wound infections has been reported in patients older than 66 years compared with patients younger than 14 years of age.20 The use of routine perioperative antibiotics, minimizing operative times, appropriate postoperative wound care, and attention to nutritional status all may decrease this risk.

Spinal Disorders in the Elderly Patient

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is a state of decreased density of mineralized bone. The biochemical makeup and structure of osteoporotic bone are normal, but the volume density of bone is below normal. Bone mass reaches its maximum in the third decade of life and then begins to decrease.21 At its peak, the maximum surface area of bone crystals in an adult is estimated to be 100 acres.

Loss of bone mineral content predominantly occurs from trabecular bone because of its increased baseline metabolic activity and greater surface area compared with cortical bone. Hence, structures formed of trabecular bone are more susceptible to osteoporosis.22 In vertebral bodies, trabecular bone accounts for 90% of axial load-bearing resistance. As a result of primary osteoporosis, elderly people may sustain vertebral compression fractures with minimal trauma. Current recommendations for the medical management of osteoporosis are summarized in Box 131-2.

Bone densitometry has been shown to predict risk of osteoporosis.23 Currently, two methods are used to evaluate bone density. Dual-energy radiography measures area density (g/cm2) of the spine. This test is simple and accurate and carries a low radiation dose. It is also well tolerated, with a procedure time of 10 to 15 minutes. Quantitative CT scanning is a measurement of true density (g/cm3) through a cross-sectional view of the vertebral body. The precision of this test is excellent, but it can be compromised by patient positioning and movement. The small increase in accuracy provided by this test over dual-energy radiography may not justify the expense, discomfort, and added radiation dose.24 A bone mineral density by dual-energy radiography of 1 g/cm2 carries a fracture risk over time of 32%, whereas a density of less than 0.8 g/cm2 carries a risk of 50%.25,26

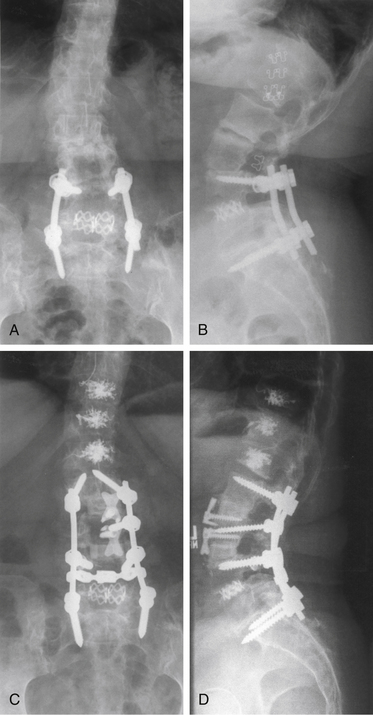

The effect of osteoporosis on vertebrae adjacent to areas of spinal fusion must also be considered. In elderly or osteoporotic patients in whom long fusion constructs are unavoidable, the long-term stability of adjacent vertebral segments is a significant concern. Particularly for areas of high mechanical stress, such as fusions stopping at the thoracolumbar junction, consideration should be given to prophylactic enhancement of the strength of vertebrae adjacent to long fusion constructs through procedures such as vertebroplasty27 (Fig. 131-1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree