The Hypoglossal Nerve

The hypoglossal nerve (CN XII) is a purely motor nerve, supplying the tongue. Its cells of origin are in the hypoglossal nuclei. The paired nuclei extend almost the entire length of the medulla just beneath the floor of the fourth ventricle, close to the midline, under the medial aspect of the hypoglossal trigone. The nerve emerges from the medulla in the sulcus between the pyramid and inferior olive as a series of 10 to 15 rootlets on each side, anterior to the rootlets of CNs IX, X, and XI.

The nerve passes through the hypoglossal canal, descends the neck to the level of the angle of the mandible, then passes forward under the tongue to supply its extrinsic and intrinsic muscles. In the upper portion of its course, the nerve lies beneath the internal carotid artery and internal jugular vein, and near the vagus nerve. It passes between the artery and vein, runs forward above the hyoid bone, and breaks up into a number of fibers to supply the various tongue muscles. At the base of the tongue it lies near the lingual branch of the mandibular nerve.

The cerebral center regulating tongue movements lies in the lower portion of the precentral gyrus near and within the sylvian fissure. The supranuclear fibers run in the corticobulbar tract through the genu of the internal capsule and through the cerebral peduncle. Supranuclear control to the genioglossus muscle is primarily crossed; supply to the other muscles is bilateral but predominantly crossed.

Examination of the Hypoglossal Nerve

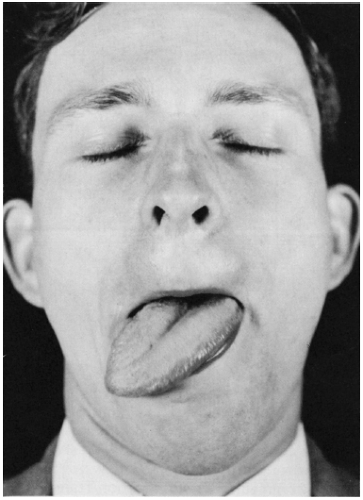

The clinical examination of hypoglossal nerve function consists of evaluating the strength, bulk, and dexterity of the tongue—looking especially for weakness, atrophy, abnormal movements (particularly fasciculations), and impairment of rapid movements. After noting the position and appearance of the tongue at rest in the mouth, the patient is asked to protrude it, move it in and out, from side to side, and upward and downward, both slowly and rapidly. Motor power can be tested by having the patient press the tip against each cheek as the examiner tries to dislodge it with finger pressure. The normal tongue is powerful and cannot be moved. For more precise testing, press firmly with a tongue blade against the side of the protruded tongue, comparing the strength on the two sides.

When unilateral weakness is present, the tongue deviates toward the weak side on protrusion because of the action of the normal genioglossus, which protrudes the tip of the tongue by drawing the root forward (Figure 16.1). Because the tip of the tongue is pushed out of the mouth it deviates toward the weak side. There is impairment of the ability to deviate the protruded tongue toward the nonparetic side and of the ability to push the tongue against the cheek on the normal side, but the patient is able to push it against the cheek on the weak side. Lateral movements of the tip of the nonprotruded tongue, controlled by the intrinsic tongue muscles, may be preserved.

Because of the extensive interlacing of muscle fibers from side to side, the functional deficit with unilateral tongue weakness may be minimal. There may be difficulty manipulating food in the mouth, and an inability to remove food from between the teeth and the cheeks on either side. With either weakness or incoordination, rapid tongue movements may be impaired. In bilateral paralysis, the patient may be able to protrude the tongue only slightly, or not at all.

Because of the extensive interlacing of muscle fibers from side to side, the functional deficit with unilateral tongue weakness may be minimal. There may be difficulty manipulating food in the mouth, and an inability to remove food from between the teeth and the cheeks on either side. With either weakness or incoordination, rapid tongue movements may be impaired. In bilateral paralysis, the patient may be able to protrude the tongue only slightly, or not at all.

FIGURE 16.1 • Infranuclear paralysis of muscles supplied by the hypoglossal nerve: Unilateral atrophy and deviation of the tongue following a lesion of the right hypoglossal nerve. |

Facial muscle weakness or jaw deviation makes it difficult to evaluate deviation of the tongue. Patients with significant lower facial weakness often have distortion of the normal facial appearance that can produce the appearance of tongue deviation when none is present (Figure 11.1). Protruding the tongue may cause an appearance of deviation toward the side of the facial weakness. Because of the lack of facial mobility the corner of the mouth does not move out of the way and the protruded tongue lies tight against it, making it look as though the tongue has deviated. Manually pulling up the weak side of the face eliminates the “deviation.” It may also be helpful to gauge tongue position in relation to the tip of the nose or the notch between the upper incisors.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree