Patients are even more secretive about drug habits. Tactful opening questions might be to ask whether the patient has ever used drugs for other than medicinal purposes, ever abused prescription drugs, or ever ingested drugs other than by mouth. The vernacular is often necessary. Patients understand smoke crack better than inhale cocaine. It is useful to know the street names of commonly abused drugs, but these change frequently as both slang and drugs go in and out of fashion (a small selection of common slang drug names includes the following: cannabis—pot, grass, weed, or joint; amphetamines—speed, uppers, meth, crystal; cocaine—coke, crack, snow, white lady; barbiturates—downers, barbs, yellow jackets, red/blue devils; heroin or other opiates—junk, scag, dope, horse, smack, dreamer; PCP—angel dust, supergrass; LSD—acid, purple haze; ecstacy—E, X, XTC, disco biscuits; ketamine—special K; and nitrous oxide—whippets). A less refined type of substance abuse is to inhale common substances, such as spray paint, airplane glue, paint thinner, and gasoline. It is astounding what some individuals will do. One patient was fond of smoking marijuana and inhaling gasoline—specifically, leaded gasoline—so that he could hallucinate in color. The abuse of prescription drugs has become a major public health problem and is far more prevalent than the abuse of illicit drugs. As much as 20% of the US population is estimated to have abused prescription drugs, including opiate painkillers, sedatives, tranquilizers, and stimulants. Abuse of such drugs as hydrocodone, oxycodone, alprazolam, and clonazepam is common. Abuse of long acting oxycodone (oxy, OCs, oxycet, hillbilly heroin) is particularly problematic.

Determining if the patient has ever engaged in risky sexual behavior is sometimes important, but the subject is always difficult to broach. Patients are often less reluctant to discuss the topic than the examiner. Useful opening gambits might include how often and with whom the patient has sex, whether the patient engages in unprotected sex, or whether the patient has ever had a sexually transmitted disease (STD).

REVIEW OF SYSTEMS

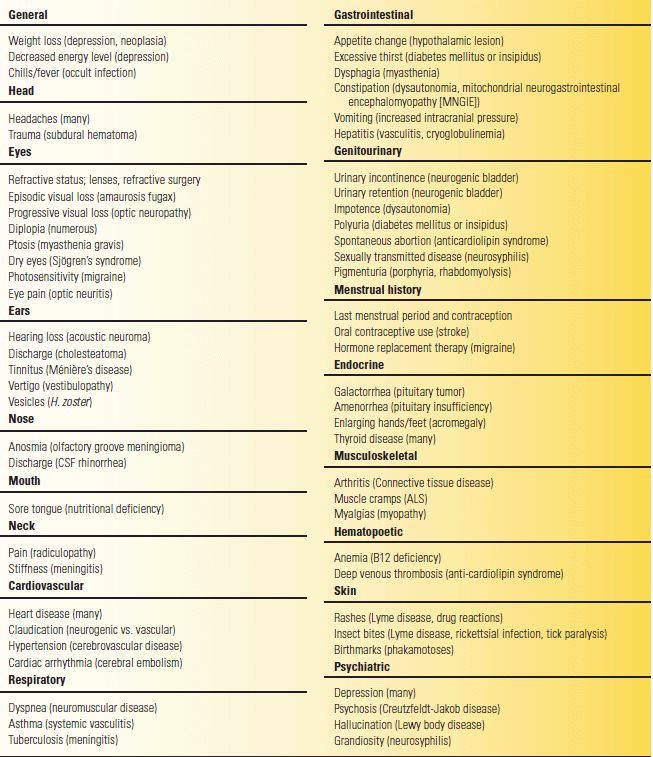

In primary care medicine, the review of systems (ROS) is designed in part to detect health problems of which the patient may not complain, but which nevertheless require attention. In specialty practice, the ROS is done more to detect symptoms involving other systems of which the patient may not spontaneously complain but that provide clues to the diagnosis of the presenting complaint. Neurologic disease may cause dysfunction involving many different systems. In patients presenting with neurologic symptoms, a neurologic ROS is useful after exploring the present illness to uncover relevant neurologic complaints. Some question areas worth probing into are summarized in Table 3.2. Symptoms of depression are often particularly relevant and are summarized in Table 3.3. A more general ROS may also reveal important information relevant to the present illness (Table 3.4). Occasionally, patients have a generally positive ROS, with complaints in multiple systems out of proportion to any evidence of organic disease. Patients with Briquet’s syndrome have a somatization disorder with multiple somatic complaints, which they often describe in colorful, exaggerated terms.

TABLE 3.2 A Neurologic System Review: Symptoms Worth Inquiring About in Patients Presenting with Neurologic Complaints

Modified from: Campbell WW, Pridgeon RP. Practical Primer of Clinical Neurology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2002.

TABLE 3.3 Some Symptoms Suggesting Depression

Modified from: Campbell WW, Pridgeon RP. Practical Primer of Clinical Neurology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2002.

TABLE 3.4 Items in the Review of Systems of possible Neurologic Relevance, with Examples of Potentially Related Neurologic Conditions in Parentheses

The ROS is often done by questionnaire in outpatients. Another efficient method is to do the ROS during the physical examination, asking about symptoms related to each organ system as it is examined.

HISTORY IN SOME COMMON CONDITIONS

Some of the important historical features to explore in patients with some common neurologic complaints are summarized in Tables 3.5 through 3.13. There are too many potential neurologic presenting complaints to cover them all, so these tables should be regarded only as a starting point and an illustration of the process. Space does not permit an explanation of the differential diagnostic relevance of each of these elements of the history. Suffice it to say that each of these elements in the history has significance in ruling in or ruling out some diagnostic possibility. Such a “list” exists for every complaint in every patient. Learning and refining these lists is the challenge of medicine.

For example, Table 3.5 lists some of the specific important historical points helpful in evaluating the chronic headache patient. The following features are general rules and guidelines, not absolutes. Patients with migraine tend to have unilateral hemicranial or orbitofrontal throbbing pain associated with gastrointestinal (GI) upset. Those suffering from migraine with aura (classical migraine) have visual or neurologic accompaniments. Patients usually seek relief by lying quietly in a dark, quiet environment. Patients with cluster headache tend to have unilateral nonpulsatile orbitofrontal pain with no visual, GI, or neurologic accompaniments; they tend to get some relief by moving about. Patients with tension type headaches tend to have nonpulsatile pain which is band-like or occipitonuchal in distribution and unaccompanied by visual, neurologic, or GI upset.

TABLE 3.5 Important Historical Points in the Chronic Headache Patient

Modified from: Campbell WW, Pridgeon RP. Practical Primer of Clinical Neurology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2002.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree