The Proprioceptive Sensations

The proprioceptive sensations arise from the deeper tissues of the body, principally from the muscles, ligaments, bones, tendons, and joints. Proprioception has both a conscious and an unconscious component. The conscious component travels with the fibers subserving fine, discriminative touch; the unconscious component forms the spinocerebellar pathways. The conscious proprioceptive sensations that can be tested clinically are motion, position, vibration, and pressure.

SENSES OF MOTION AND POSITION

The sense of motion consists of an awareness of motion of various parts of the body. The sense of position, or posture, is awareness of the position of the body or its parts in space. These sensations depend on impulses arising as a result of motion of the joints and of lengthening and shortening of the muscles. Motion and position sense are usually tested together, by passively moving a part and noting the patient’s appreciation of the movement and recognition of the direction, force, and range of movement; the minimum angle of movement the patient can detect; and the ability to judge the position of the part in space. In the lower extremity, testing usually begins at the metatarsophalangeal joint of the great toe, in the upper extremity at one of the distal interphalangeal joints. If these distal joints are normal there is no need to test more proximally. Testing is done with the patient’s eyes closed. It is extremely helpful to instruct the patient, eyes open, about the responses expected before beginning the testing. No matter the effort, nonsensical replies are frequent. The examiner should hold the patient’s completely relaxed digit on the sides, away from the neighboring digits, parallel to the plane of movement, exerting as little pressure as possible to eliminate clues from variations in pressure. If the digit is held dorsoventrally, the grip must be firm and unwavering so that the pressure differential to produce movement provides no directional clue. The patient must relax, and not attempt any active movement of the digit that may help to judge its position. The part is then passively moved up or down, and the patient is instructed to indicate the direction of movement from the last position (Figure 24.1). Even when instructed that the response is two alternatives, forced choice, up or down, some patients cannot be dissuaded from reporting the absolute position (e.g., down), even if the movement was up from a down position; a surprising number insist on telling the examiner the digit is “straight” when it is moved into that position. It is often useful simply to ask the patient to report when he first detects movement, then move the digit up and down in tiny increments, gradually increasing the excursion until the patient is aware of the motion. Quick movements are more easily detected than very slow ones. Healthy young individuals

can detect great toe movements of about 1 mm; in the fingers virtually invisible movements at the distal interphalangeal joint are accurately detected. There is some rise in the threshold for movement and position sense with advancing age.

can detect great toe movements of about 1 mm; in the fingers virtually invisible movements at the distal interphalangeal joint are accurately detected. There is some rise in the threshold for movement and position sense with advancing age.

Minimal impairment of position sense causes first loss of the sense of position of the digits, then of motion. In the foot these sensations are lost in the small toes before they disappear in the great toe; in the hand involvement of the small finger may precede involvement of the ring, middle, or index finger, or thumb. Loss of small movements in the midrange is of dubious significance, especially in an older person. Loss of ability to detect the extremes of motion of the great toe is abnormal at any age. Errors between these two extremes require clinical correlation. If the senses of motion and position are lost in the digits, one should examine more proximal joints, such as ankle, wrist, knee, or elbow. Abnormality at such large joints is invariably accompanied by significant sensory ataxia and other neurologic abnormalities.

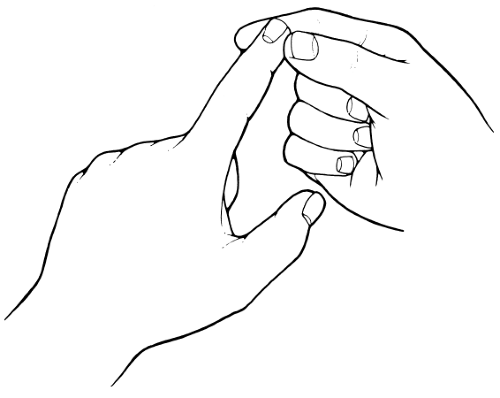

Position sense may also be tested by placing the fingers of one of the patient’s hands in a certain position (e.g., the “OK” sign) while his eyes are closed, and then asking him to describe the position or to imitate it with the other hand. The foot may be passively moved while the eyes are closed, and the patient asked to point to the great toe or heel. With the hands outstretched and eyes closed, loss of position sense may cause one hand to waver or droop. One of the outstretched hands may be passively raised or lowered, and the patient asked to place the other extremity at the same level. One hand may be passively moved, with eyes closed, and the patient asked to grasp the thumb or forefinger of that hand with the opposite hand. Abnormal performance on these latter tests does not indicate the side of involvement when a unilateral lesion is present. Loss of position sense may cause involuntary, spontaneous movements (pseudoathetosis, Figure 21.3). Reduction in the ability to perceive the direction of passive skin movement may indicate impairment of position sense superficial to the joint. Such impairment is usually associated with joint-sense deficit as well. In the pinch-press test, the patient is asked to tell if the examiner is lightly pinching or pressing the skin. Neither stimulus should be sufficiently intense to cause pain. The methods available for evaluating the senses of motion and position are all relatively crude, and there may be functional impairment not adequately brought out by the testing procedures.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree