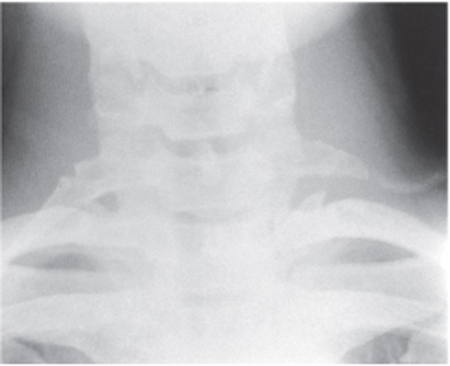

12 Thoracic Outlet Syndrome This 18-year-old, right-handed female was referred by a neurologist with a 5-year history of progressive, relatively painless, weakness and atrophy of the right hand. There was no history of significant trauma or symptoms involving the other extremities. When using her right arm overhead, she noted a dull aching sensation in the inner arm and forearm, along with paresthesias in the ulnar aspect of the hand. She reported dropping things from her right hand and had difficulty buttoning her shirt with that hand. Her general examination was notable for a long, thin neck and poor posture. Neurologically, there was full strength, bulk, and tone of all muscle groups with the exception of the intrinsic muscles of the right hand. There was dramatic atrophy of the thenar eminence with lesser involvement of the interossei and hypothenar eminence (Fig. 12–1). Pinprick and light-touch sensation were diminished in the ulnar aspect of the hand extending into the distal medial forearm. There was no reflex asymmetry and no cranial nerve findings (specifically, no Horner syndrome) or alteration in sweating. Peripheral pulses were full but elevation of the arms to shoulder level obliterated the radial pulses bilaterally. There was no supraclavicular bruit but there was tenderness over the right supraclavicular fossa with a Tinel sign upon percussion or deep palpation. Ninety-degree abduction and external rotation (AER) of the right arm reproduced the deep aching pain in the medial forearm and hand. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the cervical spine was normal. Plain cervical spine films showed bilateral cervical ribs. Electromyographic (EMG) studies demonstrated fibrillation potentials in the abductor pollicis brevis, first dorsal interosseous, and abductor digiti minimi. Nerve conduction studies showed low-amplitude median compound motor unit action potentials, low-amplitude ulnar sensory and motor action potentials, and normal median sensory potentials. Figure 12–1 Classic findings of atrophy of both median and ulnar nerve innervated intrinsic hand muscles in a patient with true neurogenic right-sided thoracic outlet syndrome (the so-called Gilliatt-Sumner hand). This 40-year-old right-handed male construction worker was referred by his company physician for evaluation of a chronic pain syndrome due to a work-related injury of his neck, right shoulder, and arm. He was well until 2 years ago when he suffered a blunt injury to the right side of his neck, shoulder, and upper arm while driving a construction vehicle. Radiographic studies were unrevealing with the exception of diffuse spondylotic changes in the cervical spine. He pursued physical therapy, which included a “work-hardening” program, without success. He tried a variety of antiinflammatory and muscle relaxant agents without relief, and currently received daily narcotic medication through a pain-management specialist. He described diffuse right-sided neck, shoulder, arm, forearm, and hand pain, which was exacerbated by any type of activity, particularly with the arm elevated. The pain had both sharp and dull components as well as a burning sensation. He described intermittent color changes in the hand and generalized swelling of the extremity. At times the pain radiated to the right side of the face and even the scalp. True neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) (patient #1) Disputed (common) neurogenic TOS (patient #2) The term thoracic outlet has remained an unfortunate misnomer for this anatomical region that more properly should be designated the thoracic inlet. The neurovascular bundle, which contains the brachial plexus elements and the subclavian vessels, courses through three narrow passageways from the base of the neck toward the axilla and proximal arm. The most important of these passageways clinically is the most proximal, the interscalene triangle, which is bordered by the anterior scalene muscle anteriorly, the middle scalene muscle posteriorly, and the medial surface of the first rib inferiorly. This triangle contains the trunks of the brachial plexus and the subclavian artery. The subclavian vein crosses anterior to the anterior scalene muscle. Just distal to the interscalene triangle, the neurovascular bundle enters the costoclavicular triangle, which is bordered anteriorly by the middle third of the clavicle, posteromedially by the first rib, and posterolaterally by the upper border of the scapula. Finally, the neurovascular bundle enters the subcoracoid space beneath the coracoid process just deep to the pectoralis minor tendon. Compression or irritation of the brachial plexus elements has been described in all three of these anatomical spaces, but for practical purposes the vast majority of cases of thoracic outlet syndrome involve neural and/or vascular compression very proximally within the interscalene triangle. This has been confirmed by direct operative stimulation and recording of nerve action potentials by Dr. David Kline and colleagues. This area may be small at rest and may become even smaller with certain provocative maneuvers (e.g., abduction and external rotation of the arm). Patients frequently awaken with symptoms due to sleeping with the arm hyperabducted and externally rotated. Working with the arms overhead or even driving may typically provoke symptoms. Carrying a heavy pack over the shoulder or a heavy suitcase may produce symptoms by direct compression of the plexus or by downward traction. Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease may develop lower trunk plexopathy because of hypertrophy of the scalenes as part of the accessory muscles of respiration, in addition to elevation of the first rib. Anomalous structures may constrict the interscalene triangle further, such as cervical ribs, anomalous muscles, and a variety of fibrous bands. The latter may be the most common anatomical anomaly and may extend from the tip of an enlarged C7 transverse process to the first rib, from the Sibson fascia (the suprapleural membrane), or between the scalene muscles. TOS is one of the most controversial clinical entities in medicine. The two cases summarized here epitomize the extremes in clinical presentation, which may fall under the diagnosis of neurogenic TOS. Other patients present with findings more consistent with a vascular type of TOS, either arterial or venous. In reality, however, these categories are not mutually exclusive, and many patients present with features of both neurogenic and vascular TOS. This sub-classifi cation is further complicated by so-called vascular features, which may represent sympathetic components of a neurogenic TOS (e.g., color and temperature changes in the extremity) and swelling. The neurogenic type of TOS has been further characterized as the true neurogenic type (patient #1) or as the common or disputed neurogenic type (patient #2). As suggested in the earlier case presentations, there is a wide variety of clinical presentations that may fall under the description TOS. We will restrict our comments here to the neurogenic type of TOS, which encompasses the vast majority of patients evaluated by a neurosurgeon. The two extremes of the syndrome may be characterized by the relatively painless form in which the neurological and electrodiagnostic findings are quite dramatic (patient #1) versus the type associated with a chronic pain syndrome and little in the way of hard neurological or electrodiagnostic findings (patient #2). The classic finding in the patient with advanced, true neurogenic TOS is the so-called Gilliatt-Sumner hand (Fig. 12–1). For unclear reasons, the most dramatic degree of atrophy is seen in the abductor pollicis brevis, with lesser involvement of the interossei and hypothenar muscles. Sensory loss usually precedes the motor findings and is restricted to the ulnar aspect of the hand and forearm, as predicted by the known compression of the lower trunk, C8, and/or T1 roots primarily. Upper trunk forms of TOS have been described, but these are reports by nonneurologists evaluating patients with chronic pain syndromes rather than true neurogenic TOS. By far the more common patient referred with a diagnosis of TOS has a chronic pain syndrome with features suggestive of brachial plexus entrapment or irritation. These cases often involve a traumatic event (e.g., motor vehicle accident or work-related injury), with blunt trauma to the neck and shoulder region or traction on the extremity. Repetitive trauma in the workplace has rapidly become one of the major precipitating factors. Litigation is commonly an important element in these cases, and unfortunately this and the psychological status of the patient must be included in the clinical decision-making process. Physical examination is difficult in these patients because of the tendency to guard the extremity, to demonstrate give-way type weakness, and to provide an unreliable sensory examination. Atrophy is usually not seen, except in the truly chronic cases due to disuse. Provocative maneuvers are usually positive in a wide anatomical area, often extending outside the region innervated by the brachial plexus. The pattern of thenar (median) wasting and ulnar sensory loss is characteristic of true neurogenic TOS and distinguishes this entity from carpal tunnel syndrome and ulnar neuropathy, both of which may present with complaints of diffuse upper extremity discomfort. Indeed, some feel that the diagnosis of TOS is one of exclusion, so that the exclusion of other diagnoses such as cervical radiculopathy, carpal tunnel syndrome, ulnar neuropathy, motor neuron disease, syringomyelia, and spinal cord neoplasm is of paramount importance. Nerve conduction studies (NCSs) and EMG are often very helpful as part of the diagnostic evaluation of patients with suspected TOS. The NCSs in true neurogenic TOS show low amplitude median motor responses and ulnar sensory responses, relatively low or normal amplitude ulnar motor responses, and normal median sensory responses. The EMG study shows evidence of chronic neurogenic motor unit potential changes of increased amplitude and duration and decreased recruitment in the abductor pollicis brevis in particular, with less severe findings in the interossei and abductor digiti minimi. Findings of active axonal loss (fibrillation potentials) are usually not as prominent as the chronic changes. Electrodiagnostic tests are also important in excluding other disorders such as carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS), ulnar nerve entrapment, and cervical radiculopathy. Somatosensory evoked potentials and ulnar motor conduction velocity studies across the thoracic outlet region have not proved to be reliable diagnostic tools in cases of TOS. Radiographic studies are an important component of the diagnostic evaluation of the patient with suspected TOS. Plain films and MRI (or computed tomographic myelography) of the cervical spine are usually recommended to identify spondylotic disease and to rule out the uncommon case of spinal tumor or syrinx. Plain films with oblique views and apical lordotic chest x-ray are useful to identify an enlarged C7 transverse process or cervical rib. The presence of an elongated, tapering, downward-pointing C7 transverse process or a partial cervical rib (Fig. 12–2) strongly suggests the presence of a fibrous band extending to the first thoracic rib. These bands are usually not visible radiographically, although there are MRI reports that are encouraging. MRI of the brachial plexus region is most useful to rule out a mass lesion affecting the plexus such as a nerve sheath tumor (schwannoma or neurofibroma) or a Pancoast tumor. MR angiography (MRA) has been used to identify vascular anomalies or compression, but formal digital subtraction angiography may be needed for optimal definition of vascular anatomy. Virtually all patients with neurogenic TOS, whether the true type or the disputed type, deserve a trial of conservative management. This should include modification of activities that provoke or exacerbate symptoms, particularly hyperabduction of the arm, overhead work, carrying heavy bags with a strap over the shoulder, sleeping positions with the arm overhead, and so forth. Physical therapy should be directed at the shoulder girdle musculature and at correction of poor posture. Some rehabilitation specialists have fashioned customized braces to assist the patient in correction of posture, but these have not been universally accepted. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) units have been prescribed for patients with chronic arm pain, with generally limited success. Pain specialists often try a variety of medications, including nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents, narcotics, tricyclic and newer classes of antidepressants, anti-convulsants, and muscle relaxants. Various nerve blocks are often tried, including stellate ganglion, selective cervical root, cervical epidural, interscalene, and multiple trigger point blocks.

Case Presentations

Case Presentations

Patient #1

Patient #2

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Anatomy

Anatomy

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Diagnostic Tests

Diagnostic Tests

Management Options

Management Options

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree