Chapter 83 Treatment Guidelines for Insomnia

The Role of Clinical Practice Guidelines

Clinical practice guidelines are designed to assist the clinician with such challenges. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) defined practice guidelines as “systematically developed statements to assist practitioner and patient decisions about appropriate healthcare for specific clinical circumstances.”1,2 Practice guidelines can be classified into a number of categories, such as assessment of therapeutic effectiveness, counseling, diagnosis, evaluation, management, prevention, rehabilitation, risk assessment, screening, technology assessment, and treatment.3

In its original report, the IOM distinguished practice guidelines from related concepts including medical review criteria, standards of quality, and performance measures. The distinctions among these concepts are summarized in Box 83-1. In addition to defining practice guidelines, the IOM also identified eight attributes of good practice guidelines. These include validity, reliability or reproducibility, clinical applicability, clinical flexibility, clarity, multidisciplinary process, scheduled review, and documentation. This outline has been widely adopted in many areas of clinical medicine, including sleep medicine.

Box 83-1

Adapted from Institute of Medicine. Clinical practice guidelines: directions for a new program. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1990.

Definitions of Practice Guidelines and Related Constructs

The National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC) (www.guideline.gov) is a website supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). As of January 2009, the National Guideline Clearinghouse listed more than 2400 practice guidelines from 48 recognized clinical specialties, including sleep medicine. The NGC archives, summarizes, and classifies guidelines. It also provides a number of tools including a glossary, links to related websites, and specific tools for submitting guidelines. The NGC uses a standard summary format for clinical guidelines, including categories such as methodology, recommendations, evidence supporting the recommendations, identifying information of the sponsoring organizations and authors, and availability.

At the center of all clinical practice guidelines is some type of systematic review, which refers to a summary of the clinical literature providing a critical assessment and evaluation of all research studies that address a particular clinical issue.4 Systematic reviews often, but not always, include quantitative analyses of data, such as meta-analyses. In addition, practice guidelines must use some specific method for formulating recommendations. These may range from informal expert consensus, to more standardized methods such as the Delphi method, nominal group technique, or a consensus development conference.3 In applying guidelines and other methods of evidence-based medicine, it is also important to recognize that many factors beyond data from clinical trials influence clinical decision making. For example, the patient’s preferences, characteristics, and ability to implement a treatment; the clinician’s expertise; the availability of a treatment; and cost are all important considerations. As stated succinctly by Haynes and colleagues, “Evidence does not make decisions, people do.”5

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) provides two types of documents to guide clinical decision making. The first are standards of practice parameters, which provide physicians with clear recommendations for evaluating and managing patients with sleep disorders based on current scientific evidence in the medical literature.6 Practice parameters follow the AHRQ and NGC guidelines, and are based on exhaustive reviews of the scientific literature conducted by a task force of experts. These practice parameters undergo internal and external peer review before publication and are reviewed and updated every 3 to 5 years.

The second type of guideline provided by the AASM is clinical guidelines, which are designed to provide comprehensive recommendations for evaluation, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up for patients with sleep disorders. Clinical guidelines are designed for areas in which a lower degree of evidence may be present or in which greater individual decision making is required. Clinical guidelines incorporate the AASM’s evidence-based practice parameters and supplement them with consensus-based recommendations from a task force of experts. Clinical guidelines include methods for diagnosis, treatment options, and recommended long-term management strategies. To date, the AASM has issued two clinical guidelines, both published in the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine.7,8

In 2008, the AASM released its Clinical Practice Guideline for evaluating and managing chronic insomnia in adults.7 The strengths and limitations of the available evidence make this topic a very appropriate one for clinical guidelines. Strengths of the current available data include a large number of efficacy trials regarding both behavioral and pharmacologic treatments for insomnia. However, many limitations also exist.

There is considerably less evidence for actual effectiveness of these trials, namely, efficacy in usual care settings. Although some case series have been reported for behavioral treatment of insomnia,9 systematic effectiveness trials are not yet available. There is also fairly limited evidence regarding the direct comparative efficacy of different modalities of treatment, including direct comparisons of behavioral and pharmacologic treatments (see Chapter 79).

There is very little evidence regarding true long-term outcomes of insomnia treatments. Some behavioral treatment studies have examined follow-up intervals of up to 2 years,10,11 and some purely retrospective observational studies have examined pharmacologic treatment outcomes over approximately 10 years.12 However, these do not amount to systematic examinations of long-term effectiveness in actual patient populations.

Development of Insomnia Clinical Guidelines

The guidelines are identified as evidence-based (with level of recommendation)13 or consensus-based. Throughout the rest of the chapter, the type of recommendation—Consensus, Guideline, or Standard—is indicated in parentheses. The guidelines were reviewed by outside content experts and members of the AASM board of directors.

Evaluation

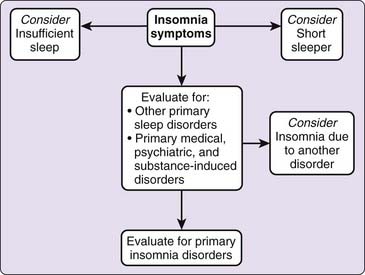

The evaluation section of the guidelines is based on previously published evidence-based standards of practice14,15 and consensus of the task force. Figure 83-1 summarizes the guideline recommendations. The central tenet of this section is that “insomnia is primarily diagnosed by clinical evaluation through a thorough sleep history and detailed medical, substance, and psychiatric history” (standard). This evaluation process can be organized into three major areas: characterization of the insomnia complaint and the consequences thereof; comprehensive assessment of sleep–wake schedule, behavior, and related symptoms; and medical and psychiatric history and examination. These inquiries may be supported by a number of questionnaires and instruments that provide additional information regarding the insomnia condition, other sleep-related symptoms (e.g., sleepiness), psychological state, daytime function, and quality of life.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree