Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy Consortium of GENESS: Treatment Results and Long-Term Outcome in 222 Patients

Classic Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy

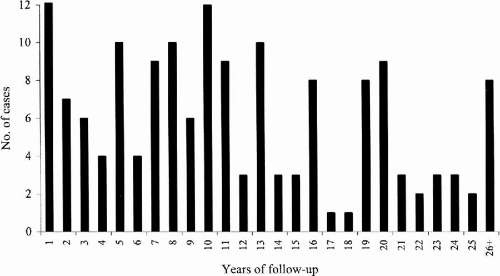

At the time we initially evaluated 161 classic JME patients (91F:60M), 60% (96/161) had myoclonic and tonic–clonic seizures, 34% (54/161) had myoclonic, tonic–clonic, and spanioleptic absence seizures, 6% (10/161) had myoclonic seizures only, and 1% (1/161) had both myoclonic and absence seizures. We were able to follow these 161 patients for a mean period of 11.6 years (range 1 to 41 years) (

Fig. 25-1); 57% were female (91/161) and 43% were male (70/161).

In evaluating the results of this long-term follow-up, we first asked how many patients were completely free of tonic–clonic grand-mal convulsions (

Table 25-1). Eighty-five percent (137/161) were free from tonic–clonic seizures, most often because of AED treatment. We then asked how many patients were completely free of all type of seizures due to AED treatment. Of the 161 patients, 72 (54%) were seizure-free and did not suffer any breakthrough seizures during the follow-up period of 10.1 years (range 1 to 41 years).

We also asked how many patients had uncontrolled seizures in spite of treatment and the reason why. At the initial portion of the follow-up period, there were 89/161 patients who identified various trigger factors as responsible for breakthrough seizures (

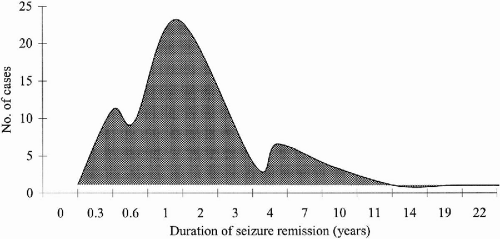

Table 25-2). In subsequent months and years of follow-up, some patients were able to correct trigger factors, such as sleep deprivation and noncompliance, thereby increasing the number of patients whose seizures completely ceased from 72 to 93. When analyzed separately, these 93 patients achieved complete freedom from seizures for a mean period of 34 months. Among them were 17 patients who were in remission from seizures for 4 to 11 years (

Fig. 25-2).

Next, we turned our attention to the 68 patients who habitually suffered breakthrough seizures in spite of recognizing the responsible trigger factors (

Table 25-2). Thirty-one of these patients only had myoclonic seizures more often on awakening. Five other patients had myoclonic and absence seizures, while 9 had breakthrough tonic–clonic grand-mal convulsions.

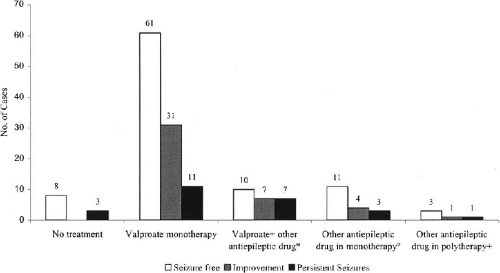

We next asked what AEDs patients were receiving, how long the patients remained seizure-free, and what were the adverse effects of AEDs. Of the 93 patients who were completely seizure-free, 85 were receiving AEDs. 60 patients (65%) were on valproate (VPA) monotherapy. They were seizure-free as long as 22 years, the mean interval of seizure-free period being 36 months.

Of seizure-free patients 11% (10/93) were receiving VPA plus one or more other AEDs. Some 15% (14/93) were taking AEDs other than VPA either as mono- or polytherapy.

Interestingly, there were eight patients (9%) who were seizure-free, but were not on any AEDs (

Fig. 25-3). Among them was one patient who had been seizure-free for 11 years.

The most common side effects in 150 patients taking AEDs were weight gain (12 patients), tremors (6 patients), hair loss (5 patients), nausea and vomiting (3 patients), polycystic ovary (2 patients), gastritis (1 patient), diarrhea (1 patient), hepatotoxicity (1 patient) and memory problems (1 patient). All side effects were observed in the group of patients taking VPA either as mono- or polytherapy. Tremor was found in one patient taking topiramate (TPM) monotherapy. Weight gain was reported also in one patient taking primidone (PRM) monotherapy.

It seemed that the more combinations of seizure types, the harder to control seizures with AEDs. Among patients presenting with myoclonic seizures only, 80% (8/10) were seizure-free. Of patients presenting myoclonic and tonic–clonic seizures, 63% (60/96) were seizure-free. On the other hand, only 46% (25/54) of patients with myoclonic, tonic–clonic, and absence seizures were seizure-free. The sole patient who had myoclonic and absence seizures had not achieved seizure control.

Among 68 patients who had recurrent seizures, 3 patients chose not to take any medication. Two were planning to get pregnant; they suffered mainly from myoclonic seizures and rare tonic–clonic convulsions. Among these 68 patients, 25 reported dissatisfaction with AED treatment because seizure frequency did not change.

Episodes of convulsive tonic–clonic status epilepticus (two patients) and myoclonic and absence status (one patient) were uncommon and were reported in only three patients. We did not observe any significant difference regarding response to treatment among women and men. Of women, 57 were seizure-free (61%), compared to 36 men (52%) who were seizure-free.

We also reviewed what AEDs patients were receiving at the time they were initially referred to our service. Among the 161 classic JME patients, 104 (64%) received carbamazepine (CBZ) and/or phenytoin (PHT) prior to referral to our service. Only 14% reported some improvement of seizures. In contrast, 14 of 21 (66%) blamed CBZ monotherapy for increasing frequencies of tonic–clonic grand mal, absence, and myoclonic seizures. PHT in combination with VPA phenobarbital (PB) or CBZ increased seizure frequency even more [18/23 or 78% of patients receiving PHT]. PHT monotherapy also aggravated seizures of nine out of 21 patients (42%). PHT in combination with VPA, PB or PRM aggravated seizures in fewer patients (8/25 or 32%). Overall, CBZ and/or PHT increased seizure frequency in 50 of 104 patients (48%). In two patients, this drug combination could have triggered the first appearance of absence seizures. Genton et al. (

1) described similar results. (

Table 25-3)

Childhood Absence Epilepsy Evolving to Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy

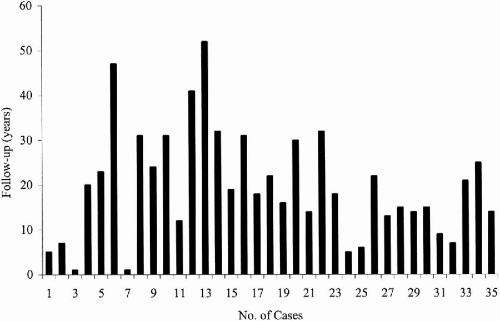

We followed 35 patients with childhood absence epilepsy (CAE) evolving to juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME) for a mean period of 19.8 years (range 1 to 47 years) (

Fig. 25-4). When initially seen, 32 had pyknoleptic absences, tonic–clonic and myoclonic seizure, and only one patient had absence and myoclonic seizures only; 66% were female (23/35) and 44% were male (12/35).

During the long period of follow-up, 3 patients among the 35 original cohort achieved complete seizure control from 2 to 40 years (

Table 25-1). Even though 32 patients had persisting seizures, VPA mono- (27 patients) or polytherapy [5 patients: combination with lamotrigine (LTG) or PB or zonisamide (ZNS) with levetiracetam (LEV)] completely suppressed tonic–clonic seizures in 23 patients (72%). Thus 26 patients out of a total number of 35, had satisfactory seizure control because grand-mal seizures had ceased. In this syndrome, absence seizures comprised the most common phenotype that persisted (16/35 patients). Rarely, breakthrough tonic–clonic (6/35 patients) and myoclonic seizures (4/35 patients) were observed.

Of three patients (3/35) who were completely free of seizures, one was taking PB and mephenytoin, another was on LEV and TPM, while one was on VPA monotherapy.

Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy with Adolescent-Onset Pyknoleptic Absence

We followed 18 patients with adolescent-onset pyknoleptic absence mixed with JME for a mean period of 13.4 years (range 5 to 26 years). A majority of patients were female (13/18 or 72%). Myoclonic, tonic–clonic, and absence seizures were present in 15/18, while 3/18 had myoclonic and absence seizures only.

Ten patients (56%) were seizure-free, while eight (44%) still had seizures. However, 7 of these 8 patients had no persisting tonic–clonic seizures, bringing a total of 17 out of 18 patients who were satisfied with seizure control because grand-mal convulsions stopped. The mean time that patients were seizure-free was 33 months. Characteristically, absences with or without myoclonic seizures persisted in 5/8. Myoclonic seizures persisted in 2/8 and tonic–clonic in one.

Seventy percent (7/10) were seizure-free on VPA monotherapy while 30% (3/10) were seizure-free on VPA associated with LTG, TPM, or LEV. Seven patients decreased seizure frequency, but in one, seizures persisted.

Side effects associated with AEDs were weight gain (three patients), depression (one patient), hair loss (one patient), hirsutism (one patient), and tremor (one patient).

PHT, CZP, PB, PRM, and ZNS had been previously used in 11/18 (61%) of the probands, but were changed due to increase in myoclonic, tonic–clonic, and absence seizures. In one patient, absence seizures appeared at 15 years of age while taking PHT and CBZ.

Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy with Astatic Seizures during Adolescence

Eight patients who had astatic seizures during adolescence were followed up for a mean period of 11.1 years (range 3–18 years). Four were female and four men. Myoclonias with or without tonic–clonic and astatic seizures were present in all patients; only one reported spanioleptic absences.

Six patients were seizure-free (6/8). One had persistent astatic seizures, while another one had breakthrough tonic–clonic seizures when carbamazepine (CBZ) levels decreased. Mean time without seizures was 20 months.

Trigger factors for seizures were awakening (four patients), noncompliance (three patients), fatigue (two patients), alcohol (one patient), light (one patient), menses (one patient), sleep deprivation (one patient), and monetary problems leading to noncompliance (one patient).

Four out of the seven patients that were seizure-free were on VPA monotherapy; of the other two, one was taking VPA plus CBZ the other was on VPA plus LTG. Reported side effects were weight gain (two patients), hair loss (one patient), and tremor (one patient).

In one patient, the previous use of CBZ and PHT was related to the appearance of the myoclonic-astatic seizures. One patient previously treated with PHT had daily astatic seizures; this patient remained seizure-free after VPA monotherapy was started. Finally, one patient with PHT and PRM had persistent tonic–clonic seizures that stopped with VPA monotherapy.