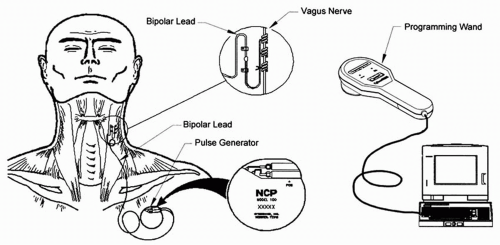

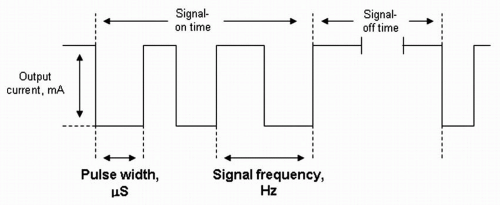

software allows placement of the programming wand over the pulse generator for reading and altering stimulation parameters (Fig. 71.2; Table 71.3). Each stimulation is preceded by 2 seconds of ramp-up time and followed by 2 seconds of ramp-down time. Two models of the VNS therapy system are currently in use: the Model 101 and the newer Model 102 (currently available only in the United States). The Model 102 titanium generator is thinner (6.9 mm), lighter (25 g), and has less volume (52.2 mm in diameter) than the previous generator models. (See the Addendum for sources of information on the VNS therapy system.)

TABLE 71.1 HISTORY OF VNS THERAPY | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TABLE 71.2 EFFICACY OF VNS THERAPY IN CLINICAL STUDIES | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

seizure-free periods after 50 months of VNS therapy with stable AED dosages (26). Seizure-free periods increased every year; one patient continued to be seizure free after 36.5 months. A prospective, open evaluation of 64 patients reported results for up to 5 years of follow up (27). No change in AED dosages occurred during the first 6 months of VNS therapy, which lasted an average of 20 months. Nineteen of 47 patients with partial seizures, five of nine with idiopathic generalized seizures, and five of eight with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome had a seizure reduction of greater than 50% or more. In this population with refractory seizures, 44% experienced a substantial reduction in severity and frequency over a long period. A recent report on long-term outcomes of 30 patients receiving VNS therapy (28) showed continued improvements over time, with 54% of patients at 1 year and 61% at 2 years exhibiting seizure frequency reductions of 50% or more compared with baseline. The mechanisms underlying the gradual improvements in response to VNS therapy seen over time in these long-term studies, however, have yet to be elucidated.

in each group also experiencing a 50% or more reduction in seizure frequency at follow-up (12 months of follow up for autism and 6 months for LKS patients). Studies have also shown both seizure frequency reductions and improved QoL among both institutionalized and noninstitutionalized patients with mental retardation/developmental delay (MRDD) (45,46). Small open studies of VNS in patients with symptomatic generalized epilepsy demonstrated reductions in seizure frequency of 41% (median) (47) and 46% (mean) (48). VNS therapy also successfully stopped a case of refractory generalized convulsive status epilepticus in a patient 13 years of age (49).

TABLE 71.3 VNS THERAPY PARAMETERS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree