What Is a Complication? Toward Objective Definition and Reporting of Adverse Outcomes

Robert A. Hart

Paul A. Anderson

Sohail Mirza

DEFINITIONS

Objective evaluation and presentation of adverse outcomes, or complications, has lagged behind objective measurement and reporting of the beneficial effects of many surgical interventions, including cervical spine procedures. A complete evaluation of competing interventions for the same clinical condition would benefit from an understanding of the negative consequences of given treatment options, in addition to the potential benefits. Several initiatives are underway that should ultimately improve the ability of clinical researchers to record and report negative outcomes using validated, objective tools in a similar way to current reporting of positive outcomes. A first requirement of such efforts is a common definition of terms. Recently, the traditional term complication has been challenged as being too narrow, with a suggested substitution of the phrase adverse event. A complication is defined as “a morbid process or event occurring during a disease that is not an essential part of the disease, although it may result from it or from independent causes” (1,2). Adverse event is a broader term, in the sense that not all adverse events result in a complication for the patient. Adverse events are defined as episodes that may affect patient outcome or that may require intervention, further diagnostic tests, or monitoring (2, 3, 4 and 5). Thus, adverse events may increase the cost and duration of a given patient care episode without ultimate negative consequences for the patient.

Considering these definitions, several additional questions arise. For example, there are adverse effects that are expected results of certain procedures, and which therefore do not require further evaluation or treatment in the majority of patients. Such adverse outcomes should be seen as inherent to a given treatment and thus do not fit well within these definitions of complication or adverse event. Examples of such outcomes include functional limitations due to cervical stiffness following fusion or laminaplasty procedures (6, 7 and 8), local pain at an autograft bone donor site, or most cases of early dysphagia or dysphonia after a ventral cervical procedure. These surgical impacts have negative effects for patients but are in most cases an expected result of the surgical procedure performed. In general, they do not relate to technical or management errors nor are they rare. Rather, as a direct result of the surgical manipulation, they must be accepted as an expected trade-off in order to obtain the intended benefits of the intervention. We suggest the term collateral outcome for such expected negative side effects of surgery.

The concept of negative outcomes should also be expanded still further from most current definitions to include impacts not only to the individual patient but also to health care organizations and greater society. As indicated in the above definition, adverse events may have limited

effect on the patient undergoing the procedure beyond lengthening their recovery or hospitalization or requiring additional diagnostic tests. In such cases, the negative consequence of the adverse event may be exclusively financial and may be primarily borne by the hospital, a commercial insurer, or by a government agency, rather than by the patient themselves. Increasingly, greater costs incurred in one procedure may reduce health care resources available to other patients or even reduce funding available to initiatives outside of the health care arena. Given current economic trends, it is increasingly important to consider costs of given procedures as negative impacts and to weigh these in decision-making regarding the relative value of various potential interventions.

effect on the patient undergoing the procedure beyond lengthening their recovery or hospitalization or requiring additional diagnostic tests. In such cases, the negative consequence of the adverse event may be exclusively financial and may be primarily borne by the hospital, a commercial insurer, or by a government agency, rather than by the patient themselves. Increasingly, greater costs incurred in one procedure may reduce health care resources available to other patients or even reduce funding available to initiatives outside of the health care arena. Given current economic trends, it is increasingly important to consider costs of given procedures as negative impacts and to weigh these in decision-making regarding the relative value of various potential interventions.

This chapter explores the current state of reporting of adverse events, both in cervical spine procedures, and more broadly in orthopaedics and other medical subspecialties. We also consider ongoing efforts to develop objective, repeatable, and validated methods to measure and report adverse events. This includes a review of work that has already been completed as well as a discussion of further appropriate steps for such efforts.

THE STATE OF CURRENT PRACTICE: HOW ARE ADVERSE EVENTS REPORTED?

A number of outcomes tools are available for use in recording and reporting beneficial effects of cervical spine surgery. Substantial work has been directed toward the development and validation of these outcomes tools, some of which are specific to spinal conditions, and some of which are more general. Examples of validated outcomes tools used in cervical spine research include the Neck Disability Index (9), cervical spine Outcomes Questionnaire (10), and the SF-36 (11).

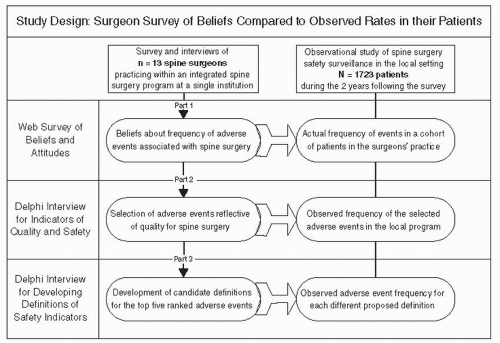

Figure 100.1. Conceptual framework for the physician surveys, interviews, and observational patient data. |

Similar efforts have not been completed for tools designed to assess adverse outcomes. As a result, clinical investigators currently lack a validated, widely accepted tool for recording and reporting adverse events. Given this, it should not be surprising to find that clinical investigators take varying approaches in the reporting of adverse consequences of treatment. In fact, it appears that there is wide variability in recording and reporting of adverse events among orthopaedic clinical researchers in other specialties, as well as those focused on the cervical spine (12, 13, 14 and 15).

A recent systematic review of randomized controlled trials of orthopaedic interventions including joint arthroplasty and fracture care demonstrated wide variation in the approach of clinical investigators to adverse event reporting (15). This included varying definitions of which adverse events to report, as well as varying techniques of recording adverse events, including which investigator was assigned to assess their occurrence. The authors concluded that a standardized protocol for assessing and reporting of complications for orthopaedic clinical trials is needed.

Within the field of spine surgery, the situation appears to be similar. Fenton et al. (14) described substantial unexplained variation in reported rates of undesirable outcomes following lumbar fusion with stand-alone interbody cages. Edwards et al. (13) assessed patients’ own reports of difficulty with swallowing and phonation following ventral cervical surgery and found much higher rates from patient self-reporting than those derived from the operating surgeon or from an assessment of the medical record. Konodi et al. (16) polled 13 spine surgeons at a single institution regarding their beliefs of frequency of complications within their own practices using the Delphi technique for consensus building (Fig. 100.1). They found that surgeons’ own estimates were not an accurate reflection based on chart reviews for complication incidence, in some cases underestimating but in other cases overestimating the frequency

of specific adverse events. These results argue for the development of standardized patient-centered outcomes tools that query for occurrence of specific consequences that surgeons and other caregivers may fail to ask about or record during routine clinical follow-up.

of specific adverse events. These results argue for the development of standardized patient-centered outcomes tools that query for occurrence of specific consequences that surgeons and other caregivers may fail to ask about or record during routine clinical follow-up.

Given the lack of uniform reporting, some efforts to gain information regarding negative impacts of spine surgery have utilized large databases as a source of comparative information regarding adverse outcomes (17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 and 23). Such databases are prone to incomplete and inaccurate data, as they are derived from billing and coding information and lack specific data regarding diagnoses, procedures, complications, and ultimate clinical outcomes. Thus, while comparisons of such data can be valid and potentially useful, they are ultimately not a satisfactory substitute for direct evaluation and reporting of adverse events. Given this, utilizing such data for policy making or clinical decision-making may be inappropriate.

Several efforts to fill this gap are underway (5,24,25). Mirza et al. recently described an index of the invasiveness of a given spine surgery as the sum of six scores regarding levels of ventral decompression, fusion, and instrumentation, along with analogous scores relating to dorsal procedures. They demonstrated a significant relationship between this index and operative time and blood loss across 1,723 spine surgeries (24). A further report from this group demonstrated a high level of agreement among independent reviewers of the etiology, preventability, and severity of 141 adverse occurrences following spine surgery, with a much higher adverse event rate recorded through a chart review by an uninvolved investigator as opposed to the reports of the treating surgeon and care team (5). Consistent feedback to surgeons regarding completion of data forms regarding surgical procedures and patients’ neurologic status did result in improvements in the accuracy and completeness of medical records over a 12 month timeframe (26). (Figs. 100.2 and 100.3)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree